Technologies of Power, Governmentality and Olympic Discourses: Using Fouca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hommage À Marcel Trigon, Maire D'arcueil De 1964 À 1997

juillet et août 2012 | n°229 Hommage à Marcel Trigon, ‘ ‘ ‘ maire d’Arcueil de 1964 à 1997 |4 | 24 | Découvertes ‘ | 32 | C’est vous qui le dites Plus vite, | 16 Après un printemps Deux ruches au-dessus de la mairie pourri, enfin le beau temps ? plus haut, | 17 Nous exigeons ‘ Le son et lumière en photos tous un été en forme vraiment plus fort, olympique. Bientôt, des conteneurs souterrains | 20 En photo : les championnats l’été ! Tout l’été, des activités pour tous de l’Association athlétique du collège Albert-le-Grand à Arcueil ‘ o’quAI (vers 1900). d’arcueil PDF(Programme compression, complet livré avec OCR, ce numéro) web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION‘ PDFCompressor‘ PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Événement Arcueil perd un homme d’exception Par Daniel Breuiller, maire d’Arcueil Notre ville est en deuil. Elle vient de perdre Marcel fit modifier le programme de sa visite d’Etat pour venir Trigon qui fut son maire pendant 33 ans et son conseiller rendre hommage à Dulcie September à Arcueil. général durant près de 20 ans. La solidarité internationale et la lutte sociale lui tenaient Comme maire, il fut un inlassable militant de la justice à cœur : lui qui avait vu un petit camarade d’école juif sociale, du logement pour tous, de la citoyenneté active déporté et assassiné combattit toute sa vie toute forme et de la solidarité internationale. Il aimait les gens et ce de racisme, d’intolérance, ou d’exclusion. -

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

U.S. Citizenship Non-Precedent Decision of the and Immigration Administrative Appeals Office Services In Re: 8865906 Date: NOV. 30, 2020 Appeal of Nebraska Service Center Decision Form 1-140, Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker (Extraordinary Ability) The Petitioner, a martial arts athlete and coach, seeks classification as an alien of extraordinary ability. See Immigration and Nationality Act (the Act) section 203(b)(l)(A), 8 U.S.C. § l 153(b)(l)(A). This first preference classification makes immigrant visas available to those who can demonstrate their extraordinary ability through sustained national or international acclaim and whose achievements have been recognized in their field through extensive documentation. The Director of the Nebraska Service Center denied the petition, concluding that the record did not establish that the Petitioner met the initial evidence requirements through receipt of a major, internationally recognized award or meeting three of the evidentiary criteria at 8 C.F.R. § 204.5(h)(3). In these proceedings, it is the Petitioner's burden to establish eligibility for the requested benefit. See Section 291 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1361. Upon de nova review, we will dismiss the appeal. I. LAW Section 203(b)(l) of the Act makes visas available to immigrants with extraordinary ability if: (i) the alien has extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics which has been demonstrated by sustained national or international acclaim and whose achievements have been recognized in the field through extensive documentation, (ii) the alien seeks to enter the United States to continue work in the area of extraordinary ability, and (iii) the alien's entry into the United States will substantially benefit prospectively the United States. -

The Rebels of 1894 and a Visionary Activist

ИСТОРИЯ Kluge V. The rebels of 1894 and a visionary activist. Science in Olympic Sport. Клюге Ф. Пьер Кубертен – дальновидный активист. Наука в олимпийском спор- 2020; 1:22-47. DOI:10.32652/olympic2020.1_2 те. 2020; 1:22-47. DOI:10.32652/olympic2020.1_2 The rebels of 1894 and a visionary activist Vollcer Kluge The rebels of 1894 and a visionary activist Vollcer Kluge АBSTRACT. The article is dedicated to Pierre de Coubertin, the French public figure and initiator of the Olympic Games re- vival. He initiated free movement of athletes, embodied the idea of peace and made a proposal to restore the Olympic Games. Coubertin couldn't remember when he thought of reviving the Olympics, but ancient Olympia had always been "a place of nostalgia" for him. However, the path to his goal realization was not easy, the sensational idea of the revival of the Olympic Games did not always find feedback, and almost no one could understand the consequences and separate the idea of Cou- bertin from ancient views of the Olympic Games. The obvious difficulties and the loss of support failed to stop the visionary aristocrat, but prompted organization of large-scale events, including the Congress of 1894, which first considered the pos- sibility of reviving the Olympic Games and the conditions for their restoration. “The project referred to in the last paragraph will rather be a pleasant expression of the international harmony to which we do not aspire, but simply envision. Restoration of the Olympic Games on the basis and in the conditions that meet the needs of modern life will gather representatives of the peoples of the world every four years, and one can think that this peaceful and polite rivalry will represent the best form of internationalism." More than once, Coubertin had to defend his idea in serious discussions, but ultimately it was agreed that the international games should be held every four years and include only amateur athletes with the exception of fencing. -

ISF 2019 Season World of School Sport

MAGAZINE Launch of the ISF 2019 Season World of School Sport p.6 She Runs - Active Girls’ Lead Project p.9 Inside ISF p.20 ISF & Youth She Runs project through the eyes of youth p.24 Interview ISF EC Member Mr Panya Hanlumyuang p.26 FEB - MAR #20 WE ARE SCHOOL SPORT 2019 2 | ISF IN MOTION ISF IN MOTION | 3 ISF Magazine | FEBRUARY - MARCH 2019 FEBRUARY - MARCH 2019 | ISF Magazine 4 | SUMMARY RENDEZ-VOUS WITH THE PRESIDENT | 5 SUMMARY "Rendez-Vous" WITH THE PRESIDENT #20 | January - March | 2019 As we begin yet another busy and eventful year, let us take a moment to reflect 2 | ISF in Motion and appreciate the success we have achieved in 2018. Follow us on 5 | I am delighted with the strides we have taken this past year and cannot thank you all enough "Rendez-Vous" with the President for the passion and dedication displayed in helping the ISF develop and grow. Nonetheless, I am happy to say that for 2019 we are not content with just sitting back and admiring our past 6 | World of school sport successes, with the new year bringing about a very important transitional period. 7 | With the close of 2018, our Executive Committee meeting hosted in Sochi, Russian Federation was able to decide upon the progression of the ISF secretariat and Committee. This outcome 8 | Food for thought was greatly needed and will help in strengthening and broadening the ISF’s ability to develop school sport and expand our reach. This will be partly thanks to the new structure involving to a higher degree, member countries, helping expand and improve our ability to provide youth 9 | She Runs - Active Girls’ Lead Project with professionally run sport events. -

TIR a LA CIBLE Il Iil T I I Il I Il

TIR A LA CIBLE OO^V^IDÉRATTIOIVS OÉIVK1RA JUBS Les épreuves de tir à la cible étaient au nombre raisons, l'âge moyen était assez élevé, nettement fusil, était très probablement Tune des plus jeunes de quatre : carabine miniature à Sn rnè.tres,^ indi aux environs de 40 ans. Il le fut pourtant un avec celle d'Haïti, FISHER, le Champion olym peu moins dans l'épreuve de la carabine où le pique individuel n'ayant que 31 ans. CROCKETT, Du Lundi 23 v.v: Vv ûv- • • • "'vV, 5 Epreuves viduelle ; armes libres, individuelle et nnr (•.iinipes.; • x>t- vainqueur avait 24 ans et le second 18 seulement. le plus jeune, 20, COULTER 27 et STOKES 26. ••jcjCx'v** x * *• pistolet ou revolver., individuelle. Elles eurent deux théâtres différents. Pour la A noter que l'équipe des Etats-Unis, victorieuse au Par contre, les équipiers Français avaient respec x'.xx- tivement 44, 42, 40, 35 et 46 ans. Mais le record au Samedi 28 Juin 1924 :"x -X X >X.Vt X.X.'; f;*1: 1M0S 120 à 134 carabine miniature, Reims, où un stand ultra- 'X'.x x'xX*,"*.X-. mo3erne lui a donné abri, en même temps qu'au d'âge doit certainement être détenu par l'équipe • x -x £- x; x- K:x .V: magnifique tournoi international qui l'a encadrée. française au pistolet, dont les membres avaient ; Pour les trois autres épreuves, un terrain spécial le plus âgé, M. DE SCHOUEN, 55 ans, le plus fut aménagé au Camp de Châlons, à proximité de jeune, DE CREQU1 MONTFORT, 47 ans, et les Mourmelon. -

Qatar's Sports Strategy: a Case of Sports Diplomacy Or Sportswashing?

Qatar’s sports strategy: A case of sports diplomacy or sportswashing? Håvard Stamnes Søyland Master in, International Studies Supervisor: PhD Marcelo Adrian Moriconi Bezerra, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon Co-Supervisor: PhD Cátia Miriam da Silva Costa, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon November, 2020 Qatar’s sports strategy: A case of sports diplomacy or sportswashing? Håvard Stamnes Søyland Master in, International Studies Supervisor: PhD Marcelo Adrian Moriconi Bezerra, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon Co-Supervisor: PhD Cátia Miriam da Silva Costa, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon November, 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Marcelo Moriconi for his help with this dissertation and thank ISCTE for an interesting master program in International Studies. I would like to thank all the interesting people I have met during my time in Lisbon, which was an incredible experience. Last but not least I would like to thank my family and my friends at home. Thank you Håvard Stamnes Søyland Resumo Em Dezembro de 2010, o Qatar conquistou os direitos para o Campeonato do Mundo FIFA 2020. Nos anos seguintes, o Qatar ganhou uma influência significativa no desporto global. Este pequeno estado desértico tem sido o anfitrião de vários eventos desportivos internacionais durante a última década e aumentou a sua presença global através do investimento em desportos internacionais, do patrocínio de negócios desportivos, da aquisição de clubes de futebol, da aquisição de direitos de transmissão desportiva e da criação de instalações desportivas de última geração. -

Womenʼs 100 Metres 51 Entrants

IAAF World Championships • Biographical Entry List (may include reserves) Womenʼs 100 Metres 51 Entrants Starts Sunday, August 11 Age (Days) Born 2013 Best Personal Best 112 BREEN Melissa AUS 22y 326d 1990 11.25 -13 11.25 -13 Won sprint double at 2012 Australian Championships ... 200 pb: 23.12 -13. sf WJC 100 2008; 1 Pacific Schools Games 100 2008; 8 WSG 100 2009; 8 IAAF Continental Cup 100 2010; sf COM 100 2010; ht OLY 100 2012. 1 Australian 100/200 2012 (1 100 2010). Coach-Matt Beckenham In 2013: 1 Canberra 100/200; 1 Adelaide 100/200; 1 Sydney “Classic” 100/200; 3 Hiroshima 100; 3 Fukuroi 200; 7 Tokyo 100; 3ht Nivelles 100; 2 Oordegem Buyle 100 (3 200); 6 Naimette-Xhovémont 100; 6 Lucerne 100 ʻBʼ; 2 Belgian 100; 3 Ninove Rasschaert 200 129 ARMBRISTER Cache BAH 23y 317d 1989 11.35 11.35 -13 400 pb: 53.45 -11 (55.28 -13). 200 pb: 23.13 -08 (23.50 -13). 3 Central American & Caribbean Champs 4x100 2011. Student of Marketing at Auburn University In 2013: 1 Nassau 400 ʻBʼ; 6 Cayman Islands Invitational 200; 4 Kingston ”Jamaica All-Comers” 100; 1 Kingston 100 ʻBʼ (May 25); 1 Kingston 200 (4 100) (Jun 8); 2 Bahamian 100; 5 Central American & Caribbean Champs 100 (3 4x100) 137 FERGUSON Sheniqua BAH 23y 258d 1989 11.18 11.07 -12 2008 World Junior Champion at 200m ... led off Bahamas silver-winning sprint relay team at the 2009 World Championships 200 pb: 22.64 -12 (23.32 -13). sf World Youth 100 2005 (ht 200); 2 Central American & Caribbean junior 100 2006; 1 WJC 200 2008 (2006-8); qf OLY 200 2008; 2 WCH 4x100 2009 (sf 200, qf 100); sf WCH 200 2011; sf OLY 100 2012. -

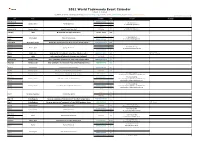

2021 World Taekwondo Event Calendar

2021 World Taekwondo Event Calendar (subject to change) ※ Grade of event is distinguished by colour: Blue-Kyorugi, Red-Poomsae, Green-Para, Purple-Junior, Orange-Team, (as of 15th January, 2021) Date Place Event Discipline Grade Contacts Remarks February 20-21 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (T) 0090 530 575 27 00 Istanbul, Turkey Turkish Open 2021 February 22 CADET N/A (E ) [email protected] February 23 JUNIOR N/A (T) 0090 530 575 27 00 February 25-26 Istanbul, Turkey Turkish Poomsae Open 2021 POOMSAE G-1 (E ) [email protected] February Online World Taekwondo Super Talent Show TALENT SHOW N/A - March 6 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) 359 8886 84548 Sofia, Bulgaria Ramus Sofia Open 2021 March 7 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E ) [email protected] March 8-10 Riyad, Saudi Arabia Riyadh 2021 World Taekwondo Women's Open Championships SENIOR KYORUGI TBD March 12 CADET N/A (T) 34 965 37 00 63 March 13 Alicante, Spain Spanish Open 2021 JUNIOR N/A (E ) [email protected] March 14 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (PSS : Daedo) March Wuxi, China Wuxi 2020 World Taekwondo Grand Slam Champions Series SENIOR KYORUGI N/A Postponed to 2021 March Online Online 2021 World Taekwondo Poomsae Open Challenge I POOMSAE G-4 March 26-27 Amman, Jordan Asian Qualification Tournament for Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games SENIOR KYORUGI N/A March 28 Amman, Jordan Asian Qualification Tournament for Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games PARA KYORUGI G-1 April 8-11 Sofia, Bulgaria European Senior Championships SENIOR KYORUGI G-2 April 19 Beirut, Lebanon 6th Asian Taekwondo Poomsae Championships POOMSAE G-4 -

Los Deportes De Exhibición En Los Juegos Olimpicos De Paris (1924)

Citius, Altius, Fortius, 1-2008, pp. 75-93 LOS DEPORTES DE EXHIBICIÓN EN LOS JUEGOS OLIMPICOS DE PARIS (1924) Thierry Terret Universidad de Lyon (Francia) Resumen: La VIII edición de los Juegos Olímpicos de verano tuvo lugar en Paris en el año 1924 desde el 15 de marzo al 27 de julio. Veinte deportes fueron propuestos incluyendo algunos llamados “deportes de exhibición” organizados en la periferia del programa oficial. En este caso, el Comité Olímpico Internacional, autorizó solamente dos deportes, uno “nacional” y el otro, de un país diferente al del anfitrión. Sin embargo el Comité Olímpico Francés (COF) triunfó en imponer más. Usando ambos archivos, el del COI y el de COF, así como también la prensa del periodo, el autor ha investigado el significado e impactos de los deportes, que fueron finalmente seleccionados como “deportes de exhibición”: ejecuciones gimnásticas, canotaje, pelota vasca, caña1, y boxeo francés. Palabras clave: Juegos Olímpicos París 1924, Juegos Olímpicos, deportes de demostración. DEMONSTRATION SPORTS AT THE OLYMPIC GAMES PARIS 1924. Abstract: The 8th Summer Olympic Games were held in Paris in 1924 from March the 15th to July the 27th. Twenty sports were proposed with more that 120 events, including some so-called “sports of demonstration”, organised in the periphery of the official program. In this last case, the IOC authorised only two sports, one “national” and the other one from a country different from the hosting country. However, the French Olympic Committee (COF) succeeded in imposing more. Using the archives of both the IOC and the COF, as well as the press, the paper explores the meaning and impacts of the sports, which were finally selected as “demonstration sports”: gymnastic performances, canoe, Basque pelota, cane and French boxing. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

NAVIGATING THE ‘DRUNKEN REPUBLIC’: THE JUNO AND THE RUSSIAN AMERICAN FRONTIER, 1799-1811 By TOBIN JEREL SHOREY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Tobin Jerel Shorey To my family, friends, and faculty mentors ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my parents and family, whose love and dedication to my education made this possible. I would also like to thank my wife, Christy, for the support and encouragement she has given me. In addition, I would like to extend my appreciation to my friends, who provided editorial comments and inspiration. To my colleagues Rachel Rothstein and Lisa Booth, thank you for all the lunches, discussions, and commiseration. This work would not have been possible without the support of all of the faculty members I have had the pleasure to work with over the years. I also appreciate the efforts of my PhD committee members in making this dream a reality: Stuart Finkel, Alice Freifeld, Peter Bergmann, Matthew Jacobs, and James Goodwin. Finally, I would like to thank the University of Florida for the opportunities I have been afforded to complete my education. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 4 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 8 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... -

2001 Report Olympic Solidarity

2001 - 2004 Quadrennial plan 2001 Report Olympic Solidarity Contents 1 Message by the Olympic Solidarity Director 2 A vast programme making everyone a winner 3 A big cheer for all our partners! 5 Changes to the Olympic Solidarity Commission 6 Structures adapted for decentralisation 7 Programmes and budgets 8 Widespread, targeted communication 10 World programmes 14 Athletes 16 Salt Lake City 2002 – NOC preparation programme 18 Olympic Scholarships for athletes “Athens 2004” 22 Athens 2004 – Team sports support grants 26 Regional and Continental Games – NOC preparation programme 28 Youth Development Programme 30 Coaches 34 Technical courses 36 Scholarships for coaches 38 Development of national coaching structure 42 NOC Management 46 NOC infrastructure 48 Sports administrators programme 50 High-level education for sports administrators 52 NOC management consultancy 54 Regional forums 56 Special Fields 60 Olympic Games participation 62 Sports Medicine 64 Sport and the Environment 66 Women and Sport 68 International Olympic Academy 70 Sport for All 72 Culture and Education 74 NOC Legacy 76 Continental programmes 80 Continental Associations take stock 82 Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa (ANOCA) 82 Pan American Sports Organisation (PASO) 84 Olympic Council of Asia (OCA) 86 The European Olympic Committees (EOC) 88 Oceania National Olympic Committees (ONOC) 90 Abbreviations 93 2 3 For Olympic Solidarity, 2001 was the first year of the new quadrennial period 2001- 2004. The main focus of these four years can be summed up in one word: decen- tralisation. The pace of the decentralisation process, which began slowly during the previous plan, has been gradually stepped up, with full co-operation between the different organisations involved and in the knowledge that the continental bodies responsible for decentralised management are suitably equipped for the task. -

AGENDA 63Rd ABU SPORTS GROUP CONFERENCE & ASSOCIATED

AGENDA 63rd ABU SPORTS GROUP CONFERENCE & ASSOCIATED MEETINGS Sept 30 – Oct 1, 2018 Venue: Banquet Room 2, Hotel YYLDYZ, Ashgabat, Turkmenistan DAY 1 : SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 08:00 - 09:00 REGISTRATION 09:00 - 10:30 Broadcast Rights Committee Meeting 10:30 - 11:00 Coffee Break 11:00 - 12:30 Finance Committee Meeting OPENING CEREMONY 14:00 - 14:10 Opening Remarks by Mr Jiang Heping, Chairperson ABU Sports Group 14:10 - 14:20 Welcome Remarks by Vice Chairman, News and Sports TVTM (TBC) Keynote Address by His Excellency, Mr. Dayanch Gulgeldiyev, Minister of Sport & Youth Policy of 14:20 - 14:30 Turkmenistan 14:30 - 14:40 Opening Remarks by Dr Javad Mottaghi, the Secretary-General ABU 14:40 - 15:00 Group Photo 15:00 - 15:30 Report by Mr Cai Yanjiang, Director of ABU Sports followed by Q&A 15:30 - 16:00 Coffee Break Members Forum Followed by Q&A & Discussion This session provides a glimpses of the sports broadcasting in different countries and the region. Selected 16:00 members share experiences, challenges and opportunities among others. Areas of focus include broadcast rights to production and transmission and technological developments. Sports Broadcasting in Turkmenistan by Host TVTM The first Presentation of the 63rd Sports Group Conference and Associated Meetings is from our host TVTM, Turkmenistan. The Secretary General of the Olympic Committee of Turkmenistan Mr Azat Myradov and the 16:00 - 16:15 Chief of Sport TV Channel of Turkmenistan Mr Resul Babayev will talk about “Weightlifting World Championship 2018 in Ashgabat. They will also share development of Sports and the new trends in Turkmenistan.