Erika Graham Name, Course Grinnell-In-London Internship Information, and Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Kensington and Chelsea

Kensington Open House London and Chelsea Self-Guided Itinerary Nearest station: Highstreet Kensington Leighton House Museum, 12 Holland Park Rd, Kensington, London W14 8LZ Originally the studio home of Lord Leighton, President of the Royal Academy, the house is one of the most remarkable buildings of 19C. The museum houses an outstanding collection of high Victorian art, including works by Leighton him- self. Directions: Walk south-west on Kensington High St/A315 towards Wrights Ln > Turn right onto Melbury Rd > Turn left onto Holland Park Rd 10 min (0.5 mi) 18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington, London W8 7BH From 1875, the home of the Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne, his wife Marion, their two children and their live-in servants. The house is recognised as the best surviving example of a late Victorian middle-class home in the UK. Directions: Walk north-east on Holland Park Rd towards St Mary Abbots Terrace > Turn right onto Melbury Rd > Turn left onto Kensington High St/A315 > Turn left onto Phillimore Gardens > Turn right onto Stafford Terrace 8 min (0.4 mi) Kensington Palace Gardens, London This wide open street runs alongside Kensington Gardens and features stereotypical architecture of the area. Large family homes line the street, most are now occupied by Embassies or other cultural companies. Page 1 Open House London Directions: Walk north-east on Stafford Terrace towards Argyll Rd > Turn right onto Argyll Rd > Turn left onto Kensington High St/A315 > Turn left onto Kensington Palace Gardens 14 min (0.7 mi) Embassy of Slovakia, Kensington, London W8 4QY Modern Brutalist-style building awarded by RIBA in 1971. -

British Design History Itinerary 2017

WINTERTHUR PROGRAM IN AMERICAN MATERIAL CULTURE EAMC 607, British Design History, 1530-1930 U.K. itinerary (short version) January 14-28, 2017 Saturday, January 14: Depart Philadelphia Sunday, January 15: Arrive London • Central London walking tour with Angus Lockyer, School for Oriental and African Studies, University of London: Southwark, City of London • Victoria & Albert Museum: Tour of Cast Room, self-guided tour of British Galleries Monday, January 16: London • East End walking tour with Angus Lockyer: Spitalsfields, Shoreditch, Hoxton • Geoffrye Museum: Tour of collections and Almshouse with Eleanor John, Director of Collections, Learning and Engagement, and Adam Bowett, Independent Furniture Historian; furniture study session with staff Tuesday, January 17: London • Hampton Court Palace: Tour of historic kitchens with Marc Meltonville, Historic Royal Palaces, Food Historian, Historic Kitchens Team; tour of King’s apartments with Sebastian Edwards, Deputy Chief Curator and Head of Collections, Historic Royal Palaces; self-guided tour of gardens Wednesday, January 18: London • St. Paul’s Cathedral: Self-guided tour • Goldsmiths’ Company: Tour of rooms Eleni Bide, Librarian; archives session; introduction to hallmarking with Eleni Bide • Museum of London: Self-guided tour of History of London galleries; exhibition “Fire! Fire!” • Wallace Collection. Collections tour with Dr. Helen Jacobsen, Senior Curator; furniture studio conservation tour with Jurgen Huber, Senior Furniture Conservator Thursday, January 19: Surrey and London • Polesden Lacey, Surrey: Garden tour with Jamie Harris, Head Gardner; “Unseen Spaces” tour with Caroline Williams, Senior Steward • Buckingham Palace: Guided tour with Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, The Royal Collection • Dennis Severs’ House: ‘Silent Night’ tour and discussion with curator David Milne Friday, January 20: London • Westminster Abbey: Self-guided tour. -

How Earl's Court Became a Crucible for the British Women's Rights Movement

thecourt Suffragette How Earl’s Court became a crucible for the British women’s rights movement ART /// Film /// F OOD /// CHELSEA ART FAIR EARL’S COURT FESTIVAL THE o’S SIMPLE ITALIAN Is 21. Director Ben Cooper 2016 is going to be another Promises rustic neighbourhood Keeping explains just what makes it bumper year for film in fun at The Indigo Hotel in different to other fairs your area Barkston Gardens Life Local thecourt CV O ER STORY Freeing Half the Human Race As people around the world celebrate International Women’s Day on March 8, Cristina Juan takes a look back on the part Earl’s Court played in the ART women’s political movement, and for a very famous resident. Emmeline Pankhurst speaking at a Trafalgar Square rally in 1916 It seems only fitting that Emmeline Pankhurst is buried at Brompton “We women suffragists have a great mission - Cemetery. Arguably the most vocal of the militant wing of the women’s the greatest mission the world has ever known. voting rights movement in the It is to free half the human race, and through that early 1900s, she had always skirted freedom save the rest” around Earl’s Court. She lived on Russell Square with her husband for memoirs. She especially mentions the militant suffrage activism in support a long period of time, but her final tri-coloured badges that she designed of the war against Germany. She also years were spent with her daughter, herself (she was an artist) and whose called on women to work in munitions Christabel, at 50 Clarendon Road huge sales raised a significant amount factories and asked for humanitarian in Notting Hill. -

Press Release Pre-Raphaelites on Paper, Leighton House Museum

PRESS RELEASE Pre-Raphaelites on Paper: Victorian Drawings from the Lanigan Collection An exhibition at Leighton House Museum organised by the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa 12 Feb 2016 – 29 May 2016 Press Preview 11 Feb 2016 Pre-Raphaelites on Paper: Victorian Drawings from the Lanigan Collection will be the first exhibition opening at Leighton House Museum in 2016, presenting an exceptional, privately- assembled collection to the UK public for the first time. Featuring over 100 drawings and sketches by the Pre- Raphaelites and their contemporaries, the exhibition is organised by the National Gallery of Canada (NGC). It expresses the richness and flair of British draftsmanship during the Victorian era displayed in the unique setting of the opulent home and studio of artist and President of the Royal Academy (PRA) Frederic, Lord Leighton. From preparatory sketches to highly finished drawings intended as works of art in themselves, visitors will discover the diverse ways that Victorian artists used drawing to further their artistic practice, creating, as they did so, images of great beauty and accomplishment. Portraits, landscapes, allegories and scenes from religious and literary works are all represented in the exhibition including studies for some of the most well-known paintings of the era such as Edward Burne- Jones’ The Wheel of Fortune (1883), Holman Hunt’s Eve of St Agnes (1848) and Leighton’s Cymon and Iphigenia (1884). With the exception of Leighton’s painting studio, the permanent collection will be cleared from Leighton House and the drawings hung throughout the historic interiors. This outstanding collection, brought together over a 30-year period by Canadian Dr. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘At home’ in Standen: A study of the Beale family’s lived experience of their late-nineteenth century Arts and Crafts home, 1890-1914 Anne Stutchbury Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex 2016 1 Statement: I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 2 Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 List of Figures 5 List of Abbreviations 19 Introduction 20 Part One: Dwelling on family history: 1840-1890 38 1.1 The early years: Birmingham and Leamington 1.2 The London years Part Two: A ‘house in the country’ 74 2.1 Locating Standen 2.2 Collaborating with Philip Webb Part Three: The ‘artists’ 98 3.1 Inspired by nature: Margaret Beale’s garden artistry 3.2 ‘A connoisseur of things beautiful’: Margaret S. Beale Part Four: Styling Standen 127 4.1 Questioning ‘Arts and Crafts’ 4.2 Aesthetic interiors: Beauty, harmony and visions of femininity Part Five: Travelling and collecting 171 5.1 Holiday hunting for furniture 5.2 European excursions and objets d'art 5.3 Exotic visions and ‘Oriental’ objects Part Six: ‘Identifying’ the Beales 197 6.1 Treasured family possessions 6.2 Renewing and refashioning old furniture Conclusion 215 Bibliography 222 Appendices A. -

Tourist Attractions in London

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU UČITELJSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA UČITELJSKE STUDIJE LUKA KRIŠTOFIĆ DIPLOMSKI RAD TOURIST ATTRACTIONS IN LONDON Čakovec, srpanj 2019. 1 SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU UČITELJSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA UČITELJSKE STUDIJE (Čakovec) DIPLOMSKI RAD Ime i prezime pristupnika: Luka Krištofić TEMA DIPLOMSKOG RADA: Tourist attractions in London MENTOR: doc. dr. sc. Vladimir Legac Čakovec, srpanj 2019. 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. 3 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 SAŽETAK ................................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 7 2. THE WEST END ..................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Westminster Abbey ........................................................................................... 8 2.2. Houses of Parliament ......................................................................................... 9 2.3. British Museum ............................................................................................... 10 2.4. Buckingham Palace ........................................................................................ -

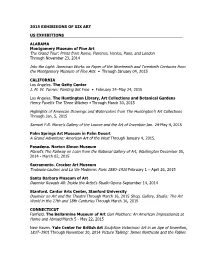

2015 Exhibitions of XIX ART

2015 EXHIBItiONS OF XIX ART US EXHIBITIONS ALABAMA Montgomery Museum of Fine Art The Grand Tour: Prints from Rome, Florence, Venice, Paris, and London Through November 23, 2014 Into the Light: American Works on Paper of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts • Through January 04, 2015 CALIFORNIA Los Angeles. The Getty Center J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free • February 24–May 24, 2015 Los Angeles. The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens Henry Fuseli’s The Three Witches • Through March 30, 2015 Highlights of American Drawings and Watercolors from The Huntington’s Art Collections Through Jan. 5, 2015 Samuel F.B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention Jan. 24-May 4, 2015 Palm Springs Art Museum in Palm Desert A Grand Adventure: American Art of the West Through January 4, 2015. Pasadena. Norton Simon Museum Manet's The Railway on Loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington December 05, 2014 - March 02, 2015 Sacramento. Crocker Art Museum Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880–1910 February 1 – April 26, 2015 Santa Barbara Museum of Art Daumier Reveals All: Inside the Artist’s Studio Opens September 14, 2014 Stanford. Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University Daumier on Art and the Theatre Through March 16, 2015 Shop, Gallery, Studio: The Art World in the 17th and 18th Centuries Through March 16, 2015 CONNECTICUT Fairfield. The Bellarmine Museum of Art Gari Melchers: An American Impressionist at Home and Abroad March 5 - May 22, 2015 New Haven. Yale Center for British Art Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Through November 30, 2014 Picture Talking: James Northcote and the Fables Through December 14, 2014 Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain Through December 14, 2014 DELAWARE Delaware Art Museum Oscar Wilde’s Salomé: Illustrating Death and Desire • February 7, 2015 - May 10, 2015 FLORIDA Gainesville. -

Newsletter 171 28/7/08 10:18 AM Page 1

Newsletter 171 28/7/08 10:18 AM Page 1 THE FURNITURE HISTORY SOCIETY Newsletter No. 171 August 2008 ‘SUCH COSTLY FURNITURE, SUCH BEDS OF STATE’*: REFLECTIONS ON THE CONSERVATION AND RE-DISPLAY OF QUEEN CHARLOTTE’S STATE BED This Summer and Autumn visitors to Hampton Court will have the opportunity to see Queen Charlotte’s magnificent bed, from the Royal Collection, for the first time in years as major conservation work reaches completion (figure 1). This work has a complex and chequered history of its own: what began in the 1950s as good, but old fashioned, restoration work transformed into conservation, only to be interrupted by the devastating fire of 1986. One of the benefits of this drawn-out process is the new information it has produced about the bed’s enigmatic past. The bed comes near the end of the line of great four-poster state beds in England. It is a relic of a bygone age of elaborate court etiquette and was probably never slept in. Within years of its creation the Royal Household had been drastically reformed and even the very proper George III and Queen Charlotte had little practical use for such empty show. As well as being a significant expression of the queen’s individual patronage and taste, its design is in the very latest neo-classical style. Unlike many eighteenth-century royal objects the precise origins of the bed are obscured among the records of the queen’s private purse (the choice of funds is significant as it betrays the Queen’s close personal interest). -

Author: Hcshannon Locations in the Victorian Art Movement, but Not

Author: HCShannon Locations in the Victorian art movement, but not limited to the original Brotherhood members as the title might lead you to believe 1. Artist Millais Lived & Died here, 2 Palace Gate, Kensington, London This is where prolific artist Millais lived and died. Notes: 2. William Morris' House & Gallery, Lloyd Park, Forest Road, London William 'Wallpaper' Morris's home turned gallery. Notes: 3. Mammoth in Chelsea, 195 King's Road, Chelsea, London This is where a Mammoth's tooth was found in 1901. Notes: 4. William Morris's Furniture, 17 Red Lion Square, Bloomsbury, London This is where William Morris designed his first furniture. Notes: 5. John Ruskin born here, 54 Hunter Street, Holborn Birthplace of a English art critic and social thinker Notes: 6. St Barnabas Preaching Riots, St Barnabas Street, Pimlico The first Oxford Movement church and scene of riots. Notes: 7. Tennyson and Townshend, Chapel House, Montpelier Row, Twickenham This is where Sir Alfred Lord Tennyson lived as poet laureate. Notes: 8. Rossetti's Grave Digging, Highgate Cemetery, London This is where Dante Gabriel Rossetti opened his wifes coffin. www.shadyoldlady.com Page 1/3 Notes: 9. Tate Britain, Sugar & Prison!, Millbank, London The Tate Britain is on the site of Millbank Prison Notes: 10. Leighton House & Arab Hall, Leighton House Museum, 12 Holland Park Road The studio-home of the Victorian artist Frederic Lord Leighton. Notes: 11. William Morris tutored here, Hoe Street, Walthamstow The place where the young William Morris was tutored. Notes: 12. The Foundling Museum, 40 Brunswick Square, London This is where London's first home for abandoned children is. -

Reading Sample

0.1_001-013_A_EINSTIEG.indd 1 29.08.16 11:22 0.1_001-013_A_EINSTIEG.indd 2 29.08.16 11:22 Lawrence Alma-Tadema At Home in Antiquity Edited for the Fries Museum by Elizabeth Prettejohn & Peter Trippi Introductions by Elizabeth Prettejohn Essays by Jan Dirk Baetens, Ivo Blom, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Markus Fellinger, Charlotte Gere, Elizabeth Prettejohn, Daniel Robbins, Marlies Stoter, Peter Trippi Highlights by Eline van den Berg, Carolyn Epps Dixon, Alistair Grant, Anne Helmreich, Ian Jenkins, Stephanie Moser, Wendy Sijnesael, Robert Verhoogt PRESTEL Munich · London · New York 0.1_001-013_A_EINSTIEG.indd 3 29.08.16 11:22 Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity has been published on the occasion of the exhibition’s presentation at: Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 1 October 2016 – 7 February 2017 Belvedere, Vienna, Austria, 24 February – 18 June 2017 Leighton House Museum, London, United Kingdom, 7 July – 29 October 2017 belvedere The exhibition Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity is part of the program Leeuwarden-Fryslân European Capital of Culture 2018. The generous support of the Turing Foundation, the Provincie Fryslân and the Mondriaan Fund provided a sound basis for organizing the exhibition at the Fries Museum. It has also been supported by the Dutch Government: an indemnity grant has been provided by the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands on behalf of the Minister of Education, Culture and Science and the Minister of Finance. We also thank the following sponsors for their support of the exhibition at the Fries Museum: BankGiro Loterij, VSBfonds, Stichting Woudsend Anno 1816, Wassenbergh-Clarijs-Fontein Foundation and Nelleke Nix Studio Gallery Press Inc. -

Tourist Attractions in London

Tourist attractions in London Krištofić, Luka Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Teacher Education / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Učiteljski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:147:125777 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-02 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zagreb Faculty of Teacher Education - Digital repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU UČITELJSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA UČITELJSKE STUDIJE LUKA KRIŠTOFIĆ DIPLOMSKI RAD TOURIST ATTRACTIONS IN LONDON Čakovec, srpanj 2019. 1 SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU UČITELJSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA UČITELJSKE STUDIJE (Čakovec) DIPLOMSKI RAD Ime i prezime pristupnika: Luka Krištofić TEMA DIPLOMSKOG RADA: Tourist attractions in London MENTOR: doc. dr. sc. Vladimir Legac Čakovec, srpanj 2019. 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. 3 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 SAŽETAK ................................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 7 2. THE WEST END ..................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Westminster Abbey ..........................................................................................