Cases of Espionage and Covert Operations in Switzerland, 1795-1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stil · Styling Dirndl Inhalt Frauen Sollten Dirndl Tragen 06

Heide Hollmer Kathrin Hollmer DirndlTrends · Traditionen · Philosophie · Pop · Stil · Styling Dirndl Inhalt Frauen sollten Dirndl tragen 06 Arbeitsdress – gestern und heute 12 Barbie und Heidi 18 Codes, brave und poppige 20 Dekolleté: Einblicke und EU-Richtlinien 26 Echtheitswert – Original und Fälschung 32 Ferien vom Ich 36 Gefährliches Virus? 42 Herzerl fürs Herzerl 46 Idylle mit Frl. Menke 50 Jauchzen, Juchzen, Jodeln 54 Kornelkirschen: Dirndl zum Vernaschen 58 Lederhosen – der moderne Kult um ein altes Stück 60 Muster, Moden und Modeschöpfer 64 Nord vs. Süd 70 Oktoberfest und andere Dirndl-Orte 74 Punk, Totenkopf und Rote Rosen 84 Qual der Wahl: Hals- und Handzier 88 Resi, i hol di mit meim Traktor ab 92 Schürze und Schleife 96 Trachten, Trends und Moden 98 Umdrehungen mit Dirndlschwung 104 Vichy und Vintage 106 Wie es Euch gefällt: Styling-Tipps und Accessoires von Kopf bis Fuß 110 Xylophon oder das Spiel mit der Illusion 116 Y-Chromosom: Sie und Er 120 Zum Schluss – Welcher Dirndl-Typ sind Sie? 122 Anhang 126 6 Frauen sollten Dirndl tragen Frauen sollten Dirndl tragen 8 Dirndl LENA HOSCHEK | Foto Lupispuma b Wiesn in München, Almrausch in Kitzbühel oder Salzburger Festspiele – immer mehr Frauen sagen Ja zum Dirndl, einem an sich schlichten, aber farbenfrohen Kleid aus eng anliegendem Oberteil und weitem Rock, das klassisch mit Bluse und Schürze kombiniert wird. Lange hatten es diejenigen Frauen für sich gepachtet, die damit ihre Liebe zur ländlich-bäuerlichen Heimat und zur Tradition zum OOAusdruck bringen wollten. Das war gestern. Heute gefällt das Dirndl auch Zeitgenossinnen, die weltweit vernetzt sind, das Englische souveräner beherrschen als irgendeinen Dialekt und überhaupt keine provinziellen Wurzeln haben. -

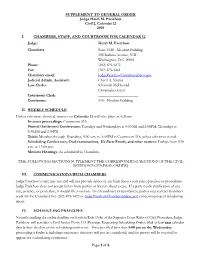

Of 6 SUPPLEMENT to GENERAL ORDER Judge Heidi M. Pasichow

SUPPLEMENT TO GENERAL ORDER Judge Heidi M. Pasichow Civil 2, Calendar 12 2019 I. CHAMBERS, STAFF, AND COURTROOM FOR CALENDAR 12 Judge: Heidi M. Pasichow Chambers: Suite 1540 - Moultrie Building 500 Indiana Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 Phone: (202) 879-1472 Fax: (202) 879-1461 Chambers email: [email protected] Judicial Admin. Assistant: Cheryl A. Simms Law Clerks: Savannah McDonald Christopher Getty Courtroom Clerk: _____________________ Courtroom: 516 - Moultrie Building II. WEEKLY SCHEDULE Unless otherwise directed, matters on Calendar 12 will take place as follows: In-court proceedings: Courtroom 516 Pretrial/Settlement Conferences: Tuesdays and Wednesdays at 9:30AM and 2:00PM; Thursdays at 9:30AM and 2:30PM Trials: Mondays through Thursdays, 9:30 a.m. to 4:45PM in Courtroom 516, unless otherwise noted. Scheduling Conferences, Oral examinations, Ex Parte Proofs, and other matters: Fridays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Motions Hearings: As scheduled by Chambers. [THE FOLLOWING SECTIONS SUPPLEMENT THE CORRESPONDING SECTIONS OF THE CIVIL DIVISION’S GENERAL ORDER] III. COMMUNICATIONS WITH CHAMBERS Judge Pasichow’s staff may not and will not provide advice of any kind about court rules, practices or procedures. Judge Pasichow does not accept letters from parties or lawyers about a case. If a party needs clarification of any rule, practice, or procedure, it should file a motion. In extraordinary circumstances, parties may contact chambers jointly via the Chambers line (202) 879-1472 or [email protected] concerning urgent scheduling issues. IV. SCHEDULING PRAECIPES Notwithstanding the earlier deadline set forth in Rule 16(b) of the Superior Court Rules of Civil Procedure, Judge Pasichow will consider a Civil Action Form 113 (Praecipe Requesting Scheduling Order) filed at least two calendar days before the date of the scheduling conference. -

Heididorf Brochure in Englisch.Pdf

english Best wishes from Heididorf Maienfeld the original Maienfeld . Graubünden . Switzerland Experience Heidi as a wonderfully likable world star at the original location at the authentic Heididorf HEIDI A WORLD STAR AT THE ORIGINAL LOCATION MAIENFELD For decades Heidi has inspired and exci- ted children from around the world and made the hearts of adults beat faster as well. Despite international appearances in musicals, anima- ted series, fi lms and books, our Heidi never forgot her roots. Nowhere else in the world is Heidi’s spirit and personality more evident than in the authentic Heididorf with Heidi’s original house, Heidi’s Alp hut, animals, museums, etc. Pure nature – Heidi’s Alp hut Heidi’s Home, Maienfeld Heidi’s house Johanna Spyri’s Heidiwelt Museum - original props and costumes from the 2015 HEIDI fi lm - biography of Johanna Spyri - all Heidi fi lms More information at..... .....www.heididorf.ch The clock is turned back to the time around 1880, when Heidi and her grandmother and all of the known people lived in a village commu- nity. The hard winters at that time presented a great challenge for these self-suffi cient people. Heidi’s house in the little village Heididorf is emotional time travel back to Animal adventures the Swiss mountain world of the late 19th cen- tury. Heidi’s and Peter’s pets greet the visitors in front of the house. A guided tour, when re- quested, shows a very authentic original Heidi world: From the cellar used to store food, you continue up to the rustic parlour, where Heidi and Geissenpeter await you. -

The Definition of Family in Johanna Spyri's Heidi (1880): A

THE DEFINITION OF FAMILY IN JOHANNA SPYRI’S HEIDI (1880): A SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of Requirement For Getting Bachelor Degree of Education In English Department by: RINI CHRISTIANA A320060060 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF TEACHING AND TRAINING EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2010 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Family is the main building block of a community, family structure and upbringing determines the social character and personality of any given society. Family is where people all learn: love, caring, compassion, ethics, honesty, fairness, common sense, reason, peaceful conflict resolution and respect for our selves and others, which are the vital fundamental skillsand family values, necessary to live an honorable and prosper life in harmony, in the world community. To have a sense of family values is to have good thoughts, good intentions and good deeds, to love and to care for those whom people are close to and are part of our primary social group, our community, such as children, parents, other family members and friends, and to treat others with the same set of values, the same way people wish to be treated. Family is important because people need a group of loyal supporters. It matters what people think and feel and nobody cares more about us than the members of our families - at least, thathow it should be and it starts from family. The more binding in the family, the better the family will be. When people can count on each other and learn on each other then family works. As the member of family, individual will be taken care and helped by the family. -

Mountain Lakes

Mountain Lakes GRAUBUNDEN SWITZERLAND TOP 7 5 Thermal waters of 1 Bad Ragaz home to Europe’s leading wellbeing and medical health Rhine Gorge 2 resort, plus the thermal waters of Vals which houses thermal baths renowned as the little Lake Caumasee designed by Pritzker awarded ‘Swiss Grand Canyon’, Peter Zumthor. boasting breathtaking one of the most beautiful lakes in views. Switzerland, home to crystal clear, turquoise-hued water. 6 St. Moritz the glitterati‘s stomping ground for luxurious hotels and all things 3 haute. Bernina Express one of the world’s most spectacular train journeys, the Albula and Bernina lines were awarded UNESCO World Heritage 4 Status. 7 Swiss National Park Sardona Tectonic Arena the first National Park established in a UNESCO World Heritage Site the Alps, and 100 years later it remains where mountains are upside down. completely unchanged. Rhine Gorge - Flims/Laax Samnaun Scuol Bad Ragaz Maienfeld Davos Klosters LONDON 1 hour G E R MANY Passugg Flims/ Laax Le Prese Valbella St. Moritz Lenzerheide Brigels Vals Traveling Around Europe Traveling across Europe while planning a trip to Graubunden is easy thanks to its central PARIS location and its great infrastructure. Either by 1 hour train or by car, Zurich is the best starting point for Graubunden. Munich and Milan are both MUNICH FRANCCE within 2h 50 min, combine them for a great addition to your trip. If you fancy a “French Flair,” why not head towards Geneva and then Paris, where you GRAUBUNDEN can even continue to London thanks to its ZURICH I T A L Y Eurostar train service. -

Auf Den Spuren Von Heidi Von Maienfeld Zur Heidialp Die

Auf den Spuren von Heidi Von Maienfeld zur Heidialp Die weltbekannte Geschichte von Heidi kann in Maienfeld erwandert und erlebt werden. Auf den Spuren von Heidi geht es in die Höhen der Bündner Herrschaft. Johanna Spyri schrieb die Bücher in den Jahren 1880 und 1881. Mit der Bahn geht es über Zürich und Sargans in die Bündner Herrschaft nach Maienfeld, das umgeben von Rebbergen am Fusse des Falknis liegt. Vom Bahnhof führt der Weg zum Heididorf in Ober-Rofels, wo sich das Heidihaus, das Johanna Spyri Museum und die neue Alphütte befinden. Nach einem kurzen Halt folgen wir dem Heidi Erlebnisweg durch den Wald und über Alpwiesen. Bei schönem Wetter kann man bei einer der zahlreichen Feuerstellen das Mittagessen aus dem Rucksack einnehmen und eine Wurst bräteln. Nach rund 1 ½ Stunden erreichen wir die Heidialp auf dem Ochsenberg. Von hier geniesst man einen eindrücklichen Rundblick über die Weinberge der Bündner Herrschaft und das Rheintal. Nach einem letzten kurzen Anstieg auf einem Wiesenpfad geht es auf einer Naturstrasse durch ein anmutendes Tal über Piols nach Jenins hinunter. Dieses malerische Dorf mit seinen prächtigen Häusern und einer denkmalgeschützten Kirche bezeichnet sich als Perle der Bündner Herrschaft. Die Gemeinde liegt am Fusse des Berges Vilan. Nun lassen wir Jenins hinter uns und durchqueren einen grossen Rebberg. Von hier lässt man den Blick nochmals über das Rheintal schweifen, bevor es zurück nach Maienfeld und mit der Bahn wieder nach Hause geht. Dölf Gabriel, Wanderleiter Wanderung vom Samstag, 16. Juni 2018. Anmelden bis 12. Juni per E-Mail [email protected] oder per Telefon 044 761 99 36 und 079 288 22 72. -

Heidi Wagner Dorn of Counsel [email protected]

Heidi Wagner Dorn Of Counsel [email protected] Columbus, OH Tel: (614) 628-6907 Heidi has nearly two decades of experience handling administrative, ethics, and litigation matters. Her practice focuses on assisting lawyers with ethics issues, including providing confidential ethics consultations and opinions, as well as comprehensive representation in disciplinary actions and bar admission matters. She also represents health care clients in administrative hearings, appeals, and other regulatory matters. As a former assistant attorney general, Heidi represented the State Medical Board of Ohio and other licensing agencies in a variety of disciplinary and licensure issues. She uses that experience to provide a unique perspective when handling her clients’ matters. Her background includes four years with the Ohio Supreme Court’s Board of Professional Conduct, where she advised the board on ethics issues and disciplinary matters, drafted advisory opinions, conducted research, and spoke at various legal forums. As an attorney who worked closely with the board and other bodies that handle disciplinary complaints against lawyers, Heidi has an understanding of ethics and disciplinary-related issues. She is able to leverage her knowledge to advise attorneys, law firms, and bar applicants about ethics issues and the best ways to handle letters of inquiry and other disciplinary matters. She provides clients an honest, straight- forward analysis of the ethical and legal issues and offers insightful strategies and advice to assist them achieve the best possible outcome. Services • Health Care Industry Education • Capital University School of Law (J.D., 2004) o Order of the Curia o Dean’s List (2002 - 2004) • University of Dayton (B.S., cum laude, 2000) o Finance o University Scholar o Women’s Rugby Club • University of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany (1998) o European Economics and Finance Bar Admissions • Ohio • Michigan Court Admissions • U.S. -

Heidi and Schellen-Ursli Are Coming to New Zealand

Heidi and Schellen-Ursli are coming to New Zealand The Embassy of Switzerland in Wellington is pleased to announce the screening of two great new Swiss family movies. Heidi is the Swiss contribution to the German Film Festival which will take place in five cities across New Zealand (Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin, New Plymouth, Auckland) in September/October 2016. A special screening of Heidi will be offered by the Embassy to the Swiss communities in Auckland and in Wellington (details will be available soon)! Schellen-Ursli (Little Mountain Boy) will be our contribution to the second edition of the Screenies Children’s Film Festival, which will take place in Auckland at the end of September 2016. Also for this movie a special screening for the Swiss community will be offered and organized in Auckland by the Embassy and the Auckland Swiss Club! The final programs of both festivals and detailed information about the special extra screenings will be available by the end of August on the Embassy Website. The Swiss Clubs will be kept informed. Stay tuned and prepare your family to meet two beloved Swiss characters for an unforgettable virtual trip to Switzerland! Heidi is a new (2015) film based on the world-famous book by Johanna Spyri. The film is directed by Alain Gsponer and it stars Anuk Steffen in the title role, alongside famous Swiss actor Bruno Ganz as Alp-öhi, Katharina Schüttler, Quirin Agrippi, Isabelle Ottmann and Anna Schinz. Schellen-Ursli is also a 2015 Swiss movie made by well-known director Xavier Koller. It is based on the book by Selina Chönz, illustrated by the artist Alois Carigiet, one of the most famous Swiss children’s books. -

Directed by Alain Gsponer

presents HEIDI Directed by Alain Gsponer “The classically fashioned feel-good feature…” – Boyd van Hoeij, The Hollywood Reporter Germany, Switzerland / 2015 / Comedy, Children’s / German, Swiss with English Subtitles; English Dub 111 min / 2.40:1 / 5.1 and 2.0 Press Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | tel: (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Film Movement Theatrical Contact: Clemence Taillandier | tel: (212) 941-7715 | [email protected] Assets: Official US Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSTBOSv71aQ Downloadable hi-res images: http://www.filmmovement.com/filmcatalog/index.asp?MerchandiseID=534 www.FilmMovement.com 1 SYNOPSIS Orphan girl Heidi spends the happiest days of her childhood with her eccentric grandfather, cut off from the outside world in a simple cabin in the Swiss mountains. Together with her friend Peter, she tends to grandfather’s goats and enjoys freedom in the mountains to the fullest. But these carefree times come to an abrupt end when Heidi is taken to Frankfurt by her Aunt Dete. The idea is for her to stay with the wealthy Sesemann family and be a playmate for his wheelchair- bound daughter Klara, under the supervision of the strict nanny, Fräulein Rottenmeier. Although the two girls soon become friends and Klara's grandmother awakes a passion for books in Heidi while teaching her to read and write, Heidi’s longing for her beloved mountains and her grandfather grows ever stronger. LOGLINE Young orphan girl Heidi lives in the Swiss Alps with her goat-herding grandfather. Forced to move into the home of an upper-class Frankfurt family, the energetic child struggles to fit in, longing for the simplicity of her life in the mountains. -

Examining Mechanisms Through Which Anime Narrative Became

The Newsletter | No.50 | Spring 2009 24 The Focus: CyberAsia Heidi in Japan What do anime dreams of Europe mean for non-Europeans? How did Heidi’s portrayal of Europe and its cultural specifi city Examining mechanisms through which anime narrative relate to its popularity? When I put this question to those I interviewed, I received diametrically opposed answers. On the became naturalised in non-Asian countries teaches us much one hand several respondents felt the power of the Afrikaans dub made people feel that the series was their own. Marida about how non-Hollywood, non-Western cultural global- Swanepoel, who was involved in the acquisition of children’s programming, said the series gave one the feeling that it had isation happened. Before anime became cool, it had braved originally been made in Afrikaans. That was certainly what I thought as a fi ve-year old Heidi fan. On the other hand, several knee-jerk dismissal and it frequently did so by entering the respondents also suggested that the European setting was a crucial contributing factor to its popularity. Kobus Geldenhuys, international market via traditionally underrated genres such who translated the script, felt that the setting appealed to Afrikaners’ cultural roots. Rina Nienaber suggested that as children’s television, with stories set in Europe or adapt- Afrikaners of the era didn’t really feel that they were living in Africa at all. Due to the overwhelming Eurocentrism of ations of European children’s books. However, as Cobus van apartheid education, the Alps felt much less exotic than South Africa’s neighbouring states. -

Preston Ridlehuber

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Preston Ridlehuber This article was written by Greg D. Tranter Preston Ridlehuber played quarterback for two seasons at the University of Georgia leading them to a Sun Bowl triumph. He played for two AFL clubs and one NFL franchise, the Oakland Raiders, Buffalo Bills, and Atlanta Falcons appearing in 22 games. Despite his limited professional playing career he is remembered for two very memorable plays in AFL history, one that forever impacted pro football on television, and the other that is one of the most improbable plays to win a game in Buffalo Bills history. Photo Credit: Robert L. Smith The New York Jets at Oakland Raiders game on November 17, 1968 changed professional football forever. A little used running back, Preston Ridlehuber, made a huge play in the last minute of the game to clinch the victory for the Raiders, that almost nobody saw. The Jets led the Raiders 32-29 with 1:01 left to play and the Raiders had the ball on their own 22-yard line following a kickoff return by Charlie Smith. It was an extremely exciting back and forth game between the two rivals, with six different lead changes, a prelude to the AFL Championship game later that season. But what this game will forever be remembered for, is with one minute and one second remaining in the exciting three point game with the time approaching 7pm on the East coast, NBC had a 1 Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com commitment to broadcast the movie Heidi at the top of the hour and broke away from the game. -

Unearthing the Therapeutic Value of Nature in Johanna Spyri's Heidi

© 2019 JETIR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Unearthing the Therapeutic Value of Nature in Johanna Spyri’s Heidi Oviya Venkateswaralu PG Student Department of English Avinashilingam Institute for Home Science and Higher Studies for Woman Coimbatore, India. Abstract: A study in the area “Therapeutic Landscapes” explores the connection between natural place and well-being. Gesler, who developed the concept of “Therapeutic Landscapes” in 1992 explains how the “healing process works itself out in places (or situations, locals, settings and milieus)” (743). The great Alps are one such therapeutic landscape which is a natural remedial place, and one will eventually forget one’s all mental and physical illness just by getting the spectacular sight of the mountain range, rocky cliffs, the glistening valleys and the pasture. About the Alpine gentians, D. H Lawrence describes as “darkening the day-time, torch- like with the smoking blueness of Pluto’s gloom” (4). The beauty, the healing magnitude and flora and fauna of Alps are vividly portrayed in one of the remarkable Swiss classics, Heidi by Johanna Spyri. The Alps and her little village become an inevitable part of Heidi's daily life. The affliction which she goes through when she parts her small village shows that the very breeze, the deep blue sky, roaring of fir-trees and wild roses became one with her soul. Moreover, the Alps here act as a therapeutic landscape in restoring both Heidi and Clara Sesemann’s natural health, thereby awakening an insight towards eco-consciousness. Index Terms – therapeutic landscapes, Alps, homesickness, eco-consciousness, psychological trauma, harmony with nature.