The Exo-Phony: Exploring Transnational Identity Through Multigenerational Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stil · Styling Dirndl Inhalt Frauen Sollten Dirndl Tragen 06

Heide Hollmer Kathrin Hollmer DirndlTrends · Traditionen · Philosophie · Pop · Stil · Styling Dirndl Inhalt Frauen sollten Dirndl tragen 06 Arbeitsdress – gestern und heute 12 Barbie und Heidi 18 Codes, brave und poppige 20 Dekolleté: Einblicke und EU-Richtlinien 26 Echtheitswert – Original und Fälschung 32 Ferien vom Ich 36 Gefährliches Virus? 42 Herzerl fürs Herzerl 46 Idylle mit Frl. Menke 50 Jauchzen, Juchzen, Jodeln 54 Kornelkirschen: Dirndl zum Vernaschen 58 Lederhosen – der moderne Kult um ein altes Stück 60 Muster, Moden und Modeschöpfer 64 Nord vs. Süd 70 Oktoberfest und andere Dirndl-Orte 74 Punk, Totenkopf und Rote Rosen 84 Qual der Wahl: Hals- und Handzier 88 Resi, i hol di mit meim Traktor ab 92 Schürze und Schleife 96 Trachten, Trends und Moden 98 Umdrehungen mit Dirndlschwung 104 Vichy und Vintage 106 Wie es Euch gefällt: Styling-Tipps und Accessoires von Kopf bis Fuß 110 Xylophon oder das Spiel mit der Illusion 116 Y-Chromosom: Sie und Er 120 Zum Schluss – Welcher Dirndl-Typ sind Sie? 122 Anhang 126 6 Frauen sollten Dirndl tragen Frauen sollten Dirndl tragen 8 Dirndl LENA HOSCHEK | Foto Lupispuma b Wiesn in München, Almrausch in Kitzbühel oder Salzburger Festspiele – immer mehr Frauen sagen Ja zum Dirndl, einem an sich schlichten, aber farbenfrohen Kleid aus eng anliegendem Oberteil und weitem Rock, das klassisch mit Bluse und Schürze kombiniert wird. Lange hatten es diejenigen Frauen für sich gepachtet, die damit ihre Liebe zur ländlich-bäuerlichen Heimat und zur Tradition zum OOAusdruck bringen wollten. Das war gestern. Heute gefällt das Dirndl auch Zeitgenossinnen, die weltweit vernetzt sind, das Englische souveräner beherrschen als irgendeinen Dialekt und überhaupt keine provinziellen Wurzeln haben. -

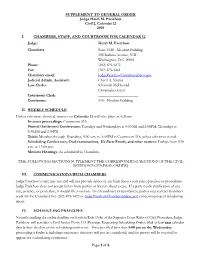

Of 6 SUPPLEMENT to GENERAL ORDER Judge Heidi M. Pasichow

SUPPLEMENT TO GENERAL ORDER Judge Heidi M. Pasichow Civil 2, Calendar 12 2019 I. CHAMBERS, STAFF, AND COURTROOM FOR CALENDAR 12 Judge: Heidi M. Pasichow Chambers: Suite 1540 - Moultrie Building 500 Indiana Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 Phone: (202) 879-1472 Fax: (202) 879-1461 Chambers email: [email protected] Judicial Admin. Assistant: Cheryl A. Simms Law Clerks: Savannah McDonald Christopher Getty Courtroom Clerk: _____________________ Courtroom: 516 - Moultrie Building II. WEEKLY SCHEDULE Unless otherwise directed, matters on Calendar 12 will take place as follows: In-court proceedings: Courtroom 516 Pretrial/Settlement Conferences: Tuesdays and Wednesdays at 9:30AM and 2:00PM; Thursdays at 9:30AM and 2:30PM Trials: Mondays through Thursdays, 9:30 a.m. to 4:45PM in Courtroom 516, unless otherwise noted. Scheduling Conferences, Oral examinations, Ex Parte Proofs, and other matters: Fridays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. Motions Hearings: As scheduled by Chambers. [THE FOLLOWING SECTIONS SUPPLEMENT THE CORRESPONDING SECTIONS OF THE CIVIL DIVISION’S GENERAL ORDER] III. COMMUNICATIONS WITH CHAMBERS Judge Pasichow’s staff may not and will not provide advice of any kind about court rules, practices or procedures. Judge Pasichow does not accept letters from parties or lawyers about a case. If a party needs clarification of any rule, practice, or procedure, it should file a motion. In extraordinary circumstances, parties may contact chambers jointly via the Chambers line (202) 879-1472 or [email protected] concerning urgent scheduling issues. IV. SCHEDULING PRAECIPES Notwithstanding the earlier deadline set forth in Rule 16(b) of the Superior Court Rules of Civil Procedure, Judge Pasichow will consider a Civil Action Form 113 (Praecipe Requesting Scheduling Order) filed at least two calendar days before the date of the scheduling conference. -

The Other Country: Stories and a Novella

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2006 The Other Country: Stories and a novella Vu Hoang Tran University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Tran, Vu Hoang, "The Other Country: Stories and a novella" (2006). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2670. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/oqxe-i2xn This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTHER COUNTRY: STORIES AND A NOVELLA by Yu Hoang Tran Bachelor of Arts University of Tulsa 1998 Master of Arts University of Tulsa 2000 Master of Fine Arts University of Iowa 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3226632 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

e cabal, from the Hebrew word qabbalah, a secret an elderly man. He is said by *Bede to have been an intrigue of a sinister character formed by a small unlearned herdsman who received suddenly, in a body of persons; or a small body of persons engaged in vision, the power of song, and later put into English such an intrigue; in British history applied specially to verse passages translated to him from the Scriptures. the five ministers of Charles II who signed the treaty of The name Caedmon cannot be explained in English, alliance with France for war against Holland in 1672; and has been conjectured to be Celtic (an adaptation of these were Clifford, Arlington, *Buckingham, Ashley the British Catumanus). In 1655 François Dujon (see SHAFTESBURY, first earl of), and Lauderdale, the (Franciscus Junius) published at Amsterdam from initials of whose names thus arranged happened to the unique Bodleian MS Junius II (c.1000) long scrip form the word 'cabal' [0£D]. tural poems, which he took to be those of Casdmon. These are * Genesis, * Exodus, *Daniel, and * Christ and Cade, Jack, Rebellion of, a popular revolt by the men of Satan, but they cannot be the work of Caedmon. The Kent in June and July 1450, Yorkist in sympathy, only work which can be attributed to him is the short against the misrule of Henry VI and his council. Its 'Hymn of Creation', quoted by Bede, which survives in intent was more to reform political administration several manuscripts of Bede in various dialects. than to create social upheaval, as the revolt of 1381 had attempted. -

Heididorf Brochure in Englisch.Pdf

english Best wishes from Heididorf Maienfeld the original Maienfeld . Graubünden . Switzerland Experience Heidi as a wonderfully likable world star at the original location at the authentic Heididorf HEIDI A WORLD STAR AT THE ORIGINAL LOCATION MAIENFELD For decades Heidi has inspired and exci- ted children from around the world and made the hearts of adults beat faster as well. Despite international appearances in musicals, anima- ted series, fi lms and books, our Heidi never forgot her roots. Nowhere else in the world is Heidi’s spirit and personality more evident than in the authentic Heididorf with Heidi’s original house, Heidi’s Alp hut, animals, museums, etc. Pure nature – Heidi’s Alp hut Heidi’s Home, Maienfeld Heidi’s house Johanna Spyri’s Heidiwelt Museum - original props and costumes from the 2015 HEIDI fi lm - biography of Johanna Spyri - all Heidi fi lms More information at..... .....www.heididorf.ch The clock is turned back to the time around 1880, when Heidi and her grandmother and all of the known people lived in a village commu- nity. The hard winters at that time presented a great challenge for these self-suffi cient people. Heidi’s house in the little village Heididorf is emotional time travel back to Animal adventures the Swiss mountain world of the late 19th cen- tury. Heidi’s and Peter’s pets greet the visitors in front of the house. A guided tour, when re- quested, shows a very authentic original Heidi world: From the cellar used to store food, you continue up to the rustic parlour, where Heidi and Geissenpeter await you. -

The Definition of Family in Johanna Spyri's Heidi (1880): A

THE DEFINITION OF FAMILY IN JOHANNA SPYRI’S HEIDI (1880): A SOCIOLOGICAL APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as Partial Fulfillment of Requirement For Getting Bachelor Degree of Education In English Department by: RINI CHRISTIANA A320060060 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF TEACHING AND TRAINING EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2010 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Family is the main building block of a community, family structure and upbringing determines the social character and personality of any given society. Family is where people all learn: love, caring, compassion, ethics, honesty, fairness, common sense, reason, peaceful conflict resolution and respect for our selves and others, which are the vital fundamental skillsand family values, necessary to live an honorable and prosper life in harmony, in the world community. To have a sense of family values is to have good thoughts, good intentions and good deeds, to love and to care for those whom people are close to and are part of our primary social group, our community, such as children, parents, other family members and friends, and to treat others with the same set of values, the same way people wish to be treated. Family is important because people need a group of loyal supporters. It matters what people think and feel and nobody cares more about us than the members of our families - at least, thathow it should be and it starts from family. The more binding in the family, the better the family will be. When people can count on each other and learn on each other then family works. As the member of family, individual will be taken care and helped by the family. -

Les Archives Du Sombre Et De L'expérimental

Guts Of Darkness Les archives du sombre et de l'expérimental avril 2006 Vous pouvez retrouvez nos chroniques et nos articles sur www.gutsofdarkness.com © 2000 - 2008 Un sommaire de ce document est disponible à la fin. Page 2/249 Les chroniques Page 3/249 ENSLAVED : Frost Chronique réalisée par Iormungand Thrazar Premier album du groupe norvégien chz le label français Osmose Productions, ce "Frost" fait suite au début du groupe avec "Vikingligr Veldi". Il s'agit de mon album favori d'Enslaved suivi de près par "Eld", on ressent une envie et une virulence incroyables dans cette oeuvre. Enslaved pratique un black metal rageur et inspiré, globalement plus violent et ténébreux que sur "Eld". Il n'y a rien à jeter sur cet album, aucune piste de remplissage. On commence après une intro aux claviers avec un "Loke" ravageur et un "Fenris" magnifique avec son riff à la Satyricon et son break ultra mélodique. Enslaved impose sa patte dès 1994, avec la très bonne performance de Trym Torson à la batterie sur cet album, qui s'en ira rejoindre Emperor par la suite. "Svarte vidder" est un grand morceau doté d'une intro symphonique, le développement est excellent, 9 minutes de bonheur musical et auditif. "Yggdrasill" se pose en interlude de ce disque, un titre calme avec voix grave, guimbarde, choeurs et l'utilisation d'une basse fretless jouée par Eirik "Pytten", le producteur de l'album: un intemrède magnifique et judicieux car l'album gagne en aération. Le disque enchaîne sur un "Jotu249lod" destructeur et un Gylfaginning" accrocheur. -

Forma Y Fondo En El Rock Progresivo

Forma y fondo en el rock progresivo Trabajo de fin de grado Alumno: Antonio Guerrero Ortiz Tutor: Juan Carlos Fernández Serrato Grado en Periodismo Facultad de Comunicación Universidad de Sevilla CULTURAS POP Índice Resumen 3 Palabras clave 3 1. Introducción. Justificación del trabajo. Importancia del objeto de investigación 4 1.1. Introducción 4 1.2. Justificación del trabajo 6 1.3. Importancia del objeto de investigación 8 2. Objetivos, enfoque metodológico e hipótesis de partida del trabajo 11 2.1. Objetivos generales y específicos 11 2.1.1. Objetivos generales 11 2.1.2. Objetivos específicos 11 2.2. Enfoque metodológico 11 2.3. Hipótesis de partida 11 3. El rock progresivo como tendencia estética dentro de la música rock 13 3.1. La música rock como denostado fenómeno de masas 13 3.2. Hacia una nueva calidad estética 16 3.3. Los orígenes del rock progresivo 19 3.4. La difícil definición (intensiva) del rock progresivo 25 3.5. Hacia una definición extensiva: las principales bandas de rock progresivo 27 3.6. Las principales escenas del rock progresivo 30 3.7. Evoluciones ulteriores 32 3.8. El rock progresivo hoy en día 37 3.9. Algunos nombres propios 38 3.10. Discusión y análisis final 40 4. Conclusiones 42 5. Bibliografía 44 5.1. De carácter teórico-metodológico (fuentes secundarias) 44 5.2. General: textos sobre pop y rock 45 5.3. Específica: rock progresivo 47 ANEXO I. Relación de documentos audiovisuales de interés 50 ANEXO II. PROGROCKSAMPLER 105 2 Resumen Este trabajo, que constituye un ejercicio de periodismo cultural, en el que se han puesto en práctica conocimientos diversos adquiridos en distintas asignaturas del Grado de Periodismo, trata de definir el concepto de rock progresivo desde dos perspectivas complementarias: una interna y otra externa. -

Challenging Stereotypes

Challenging Stereotypes How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged through the enemies in Homeland Gunhild-Marie Høie A Thesis Presented to the Departure of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree University of Oslo Spring 2014 I II Challenging Stereotypes How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged through the enemies in Homeland Gunhild-Marie Høie A Thesis Presented to the Departure of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree University of Oslo Spring 2014 III © Gunhild-Marie Høie 2014 Challenging Stereotypes: How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged in Homeland. http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo IV V Abstract Following the terrorist attack on 9/11, actions and practices of the United States government, as well as the dominant media discourse and non-profit media advertising, contributed to create a post-9/11 climate in which Muslims and Arabs were viewed as non-American. This established a binary paradigm between Americans and Muslims, where Americans represented “us” whereas Muslims represented “them.” Through a qualitative analysis of the main characters in the post-9/11 terrorism-show, Homeland, season one (2011), as well as an analysis of the opening sequence and the overall narrative in the show, this thesis argues that this binary system of “us” and “them” is no longer black and white, but blurred, and hard to define. My analysis indicates that several of the enemies in the show break with the stereotypical portrayal of Muslims as crude, violent fanatics. -

The Internal Compass

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Honors Program Theses and Projects Undergraduate Honors Program 5-9-2017 The nI ternal Compass Joshua Dyer Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Dyer, Joshua. (2017). The nI ternal Compass. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 197. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/197 Copyright © 2017 Joshua Dyer This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Internal Compass Joshua Dyer Submitted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for Departmental Honors in English Bridgewater State University May 9, 2017 Prof. Katy Whittingham, Thesis Director Prof. Nicole Williams, Committee Member Prof. Evan Dardano, Committee Member 1 The Internal Compass -Joshua Dyer 2 Epigraph Amazing Grace By John Newton “Amazing grace how sweet the sound That saved a wretch like me. I once was lost but now I'm found. Was blind but now I see. 'Twas grace that taught my heart to fear And grace my fears relieved. How precious did that grace appear The hour I first believed…” 3 Dedication For the ones that taught me that love was higher than the sky, deeper than the ocean, and more than chocolate chip pancakes. For the ones that showed me light when life seemed full of shadows. For Louise, who loved me more than I knew. 4 To Whom It Does Concern (Mrs. Robertson) To Whom It Does Concern, To you I write today, To Whom It Does Concern, I truly want to say: Thank you. -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 5292 Category 1: Public Finance April 2015

The Tax Gradient: Spatial Aspects of Fiscal Competition David R. Agrawal CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. 5292 CATEGORY 1: PUBLIC FINANCE APRIL 2015 An electronic version of the paper may be downloaded • from the SSRN website: www.SSRN.com • from the RePEc website: www.RePEc.org • from the CESifo website: www.CESifoT -group.org/wpT ISSN 2364-1428 CESifo Working Paper No. 5292 The Tax Gradient: Spatial Aspects of Fiscal Competition Abstract State borders create a discontinuous tax treatment of retail sales. In a Nash game, local tax rates will be higher on the low-state-tax side of a border. Local taxes will decrease from the nearest high-tax border and increase from the low-tax border. Using driving time from state borders and all local sales tax rates, local tax rates on the low-tax side of the border are 1.25 percentage points higher, reducing the differential in state tax rates by over three-quarters. A ten minute increase in driving time from the nearest high-tax state lowers a border town’s local tax rate by 6%. JEL-Code: H200, H250, H730, H770, R510. Keywords: sales taxes, cross-border shopping, tax competition, fiscal federalism. David R. Agrawal University of Georgia Department of Economics 527 Brooks Hall USA – Athens, GA 30602 [email protected] The author is also an Affiliate Member of CESifo. I am especially grateful to Joel Slemrod, along with David Albouy, Robert Franzese, James R. Hines Jr. I also wish to thank Claudio Agostini, Johannes Becker, Leah Brooks, Charles Brown, Raj Chetty, Paul Courant, Lucas Davis, Michael Devereux, Dhammika Dharmapala, Reid Dorsey-Palmateer, Michael Gideon, Makoto Hasegawa, William Hoyt, Ravi Kanbur, Sebastian Kessing, Miles Kimball, Michael Lovenheim, Olga Malkova, Yulia Paramonova, Raphaël Parchet, Emmanuel Saez, Stephen Salant, Nicole Scholtz, Daniel Silverman, Jeffrey Smith, Caroline Weber, and David Wildasin, as well as various conference and seminar participants. -

View the Latest Cohen Children's Medical Center

Life-saving, life-changing 2018 Annual Report Meet Brianna: When Brianna Smith, 13, was limited by a muscle disorder that affected her right hand, everyday tasks were nearly impossible. Brianna discovered that a bionic arm — a prosthetic controlled by your brain — could change her life. And, with the help of Cohen Children’s Medical Center’s orthopedic specialists, it has. Now, she has the strength and confidence to do anything. Learn more Visit pediatric orthopedics at pediatrics.northwell.edu when time is of the essence. And that’s only the Dear friends, beginning, the list goes on and on and on. We don’t invest in new programs and research For all of us at Northwell Health, the days begin and because it looks good. We invest because it makes end with our patients — we never stop thinking a difference for our patients. Our investments in about how we can best care for them, help them growth have consistently landed us on U.S. News & get stronger and keep them on the road to happy, World Report’s list of the best children’s hospitals, healthy lives. This means being the most skilled, with eight of our specialties recognized as among compassionate health care providers today and the the best in the nation. dedicated, innovative visionaries who will provide even better care tomorrow. Staying strong and sustaining growth is hard. We do it by drawing strength from our patients and their It requires a constant commitment to growing families. They are always the strongest members of and strengthening ourselves personally and in our our community.