Worlds Writ Small Four Studies on Miniature Architectural Forms in the Medieval Middle East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermal Assessment of a Novel Combine Evaporative Cooling Wind Catcher

energies Article Thermal Assessment of a Novel Combine Evaporative Cooling Wind Catcher Azam Noroozi * and Yannis S. Veneris School of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens, Section III, 42 Patission Av., 10682 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-210-772-3885 (ext. 3567) Received: 5 January 2018; Accepted: 13 February 2018; Published: 15 February 2018 Abstract: Wind catchers are one of the oldest cooling systems that are employed to provide sufficient natural ventilation in buildings. In this study, a laboratory scale wind catcher was equipped with a combined evaporative system. The designed assembly was comprised of a one-sided opening with an adjustable wetted pad unit and a wetted blades section. Theoretical analysis of the wind catcher was carried out and a set of experiments were organized to validate the results of the obtained models. The effect of wind speed, wind catcher height, and mode of the opening unit (open or closed) was investigated on temperature drop and velocity of the moving air through the wind catcher as well as provided sensible cooling load. The results showed that under windy conditions, inside air velocity was slightly higher when the pad was open. Vice versa, when the wind speed was zero, the closed pad resulted in an enhancement in air velocity inside the wind catcher. At wind catcher heights of 2.5 and 3.5 m and wind speeds of lower than 3 m/s, cooling loads have been approximately doubled by applying the closed-pad mode. Keywords: wind catcher; cooling system; experimental validation; thermal modeling 1. -

DESTINATION PROVENCE : Des Villes En Concurrence

17.03 > 14.04.18 > 17.03 ZIBELINE N°116 Mensuel culturel engagé du Sud-Est marionnettes Tricastin châteauvallon à Mougins danger en Liberté DESTINATION PROVENCE : des villes en concurrence 3€ L 11439 - 116 - F: 3,00 - RD CONTEXTE[ S ] 13 & 14 ART / TERRITOIRE AVRIL 2018 RENCONTRES & DÉBATS menés par Anne Quentin « Que faire quand la laïcité s’eff rite, que le racisme avance et que les problèmes sociaux s’aggravent ? Comment s’émanciper, grandir, rêver pour créer d’autres possibles ? De plus en plus de théâtres tentent de trouver de nouveaux ancrages à leur action pour que les lieux de l’art deviennent des lieux de vie, d’échange, de partage. CONTEXTE[S] réunit intellectuels, artistes, acteurs socio-culturels, enseignants et professionnels pour croiser points de vue et expériences et inventer ensemble des alternatives au prêt-à-consommer et au prêt-à-penser. Deux jours pour rebattre les cartes au Merlan qui fait le pari de son “contexte” pour irriguer son territoire et inventer d’autres voies à l’art. » Anne Quentin VENDREDI 13 AVRIL 14H30 ART / TERRITOIRE > TABLE 1 accueil > 14h VIVRE, RENCONTRER, INVESTIR Des habitants de Marseille et des artistes s’interrogent ensemble sur les réalités et la fonction d’un théâtre qu’ils côtoient de près ou de loin. Un temps pour faire vivre la rencontre en paroles, en récits ou témoignages autour d’un thème : le territoire peut-il réinventer l’art ? 16H30 ART / TERRITOIRE > TABLE 2 IRRIGUER, ENTREPRENDRE, AGIR Ils sont acteurs de leur territoire. Entrepreneurs, bailleurs, enseignants, travailleurs sociaux et culturels, traversent tout autant qu’ils participent du territoire. -

Egyptian Islamic and Secular Feminists in Their Own Context Assim Alkhawaja University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2015 Complexity of Women's Liberation in the Era of Westernization: Egyptian Islamic and Secular Feminists in Their Own Context Assim Alkhawaja University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Alkhawaja, Assim, "Complexity of Women's Liberation in the Era of Westernization: Egyptian Islamic and Secular Feminists in Their Own Context" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 287. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/287 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco COMPLEXITY OF WOMEN‘S LIBERATION IN THE ERA OF WESTERNIZATION: EGYPTIAN ISLAMIC AND SECULAR FEMINISTS IN THEIR OWN CONTEXT A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International & Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Assim Alkhawaja San Francisco May 2015 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Dissertation Abstract Complexity Of Women‘s Liberation in the Era of Westernization: Egyptian Islamic And Secular Feminists In Their Own Context Informed by postcolonial/Islamic feminist theory, this qualitative study explores how Egyptian feminists navigate the political and social influence of the West. -

ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage

ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 3‐6 DECEMBER 2015 GEFINOR ROTANA HOTEL BEIRUT, LEBANON ISCACH (Beirut 2015) International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 3‐6 DECEMBER 2015 GEFINOR ROTANA HOTEL BEIRUT, LEBANON © The ISCACH 2015 Organizing Committee, Beirut Lebanon All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. Title: ISCASH (International Syrian Congress on Archaeology and Cultural Heritage) 2015 Beirut: Program and Abstracts Published by the ISCACH 2015 Organizing Committee and the Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Published Year: December 2015 Printed in Japan This publication was printed by the generous support of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan ISCACH (Beirut 2015) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……….……………………………………………………….....................................3 List of Organizing Committee ............................................................................4 Program Summary .............................................................................................5 Program .............................................................................................................7 List of Posters ................................................................................................. 14 Poster Abstracts.............................................................................................. 17 Presentation Abstracts Day 1: 3rd December ............................................................................ -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 5 Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-053202-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053387-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053212-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Preface — IX Introduction — XI Chapter I Shaping Perceptions: Reading and Interpreting the Norman Arabic Textile Inscriptions — 1 1 Arabic-Inscribed Textiles from Norman and Hohenstaufen Sicily — 2 2 Inscribed Textiles and Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts — 43 3 Historical Receptions of the Ceremonial Garments from Norman Sicily — 51 4 Approaches to Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts: Methodological Considerations — 64 Chapter II An Imported Ornament? Comparing the Functions -

A Grammatical Description of Dameli

Emil Perder A Grammatical Description of Dameli Emil Perder A Grammatical Description of Dameli A Grammatical ISBN 978-91-7447-770-2 Department of Linguistics Doctoral Thesis in Linguistics at Stockholm University, Sweden 2013 A Grammatical Description of Dameli Emil Perder A Grammatical Description of Dameli Emil Perder ©Emil Perder, Stockholm 2013 ISBN 978-91-7447-770-2 Printed in Sweden by Universitetsservice AB, Stockholm 2013 Distributor: Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University ماں َتارف تہ ِاک توحفہ، دامیاں A gift from me, Dameli people Abstract This dissertation aims to provide a grammatical description of Dameli (ISO-639-3: dml), an Indo-Aryan language spoken by approximately 5 000 people in the Domel Valley in Chitral in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province in the North-West of Pakistan. Dameli is a left-branching SOV language with considerable morphological complexity, particularly in the verb, and a complicated system of argument marking. The phonology is relatively rich, with 31 consonant and 16 vowel phonemes. This is the first extensive study of this language. The analysis presented here is based on original data collected primarily between 2003-2008 in cooperation with speakers of the language in Peshawar and Chitral, including the Domel Valley. The core of the data consists of recorded texts and word lists, but questionnaires and paradigms of word forms have also been used. The main emphasis is on describing the features of the language as they appear in texts and other material, rather than on conforming them to any theory, but the analysis is informed by functional analysis and linguistic typology, hypotheses on diachronical developments and comparisons with neighbouring and related languages. -

The Wind-Catcher, a Traditional Solution for a Modern Problem Narguess

THE WIND-CATCHER, A TRADITIONAL SOLUTION FOR A MODERN PROBLEM NARGUESS KHATAMI A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/ Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2009 I R11 1 Certificate of Research This is to certify that, except where specific reference is made, the work described in this thesis is the result of the candidate’s research. Neither this thesis, nor any part of it, has been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University. Signed ……………………………………… Candidate 11/10/2009 Date …………………………………....... Signed ……………………………………… Director of Studies 11/10/2009 Date ……………………………………… II Abstract This study investigated the ability of wind-catcher as an environmentally friendly component to provide natural ventilation for indoor environments and intended to improve the overall efficiency of the existing designs of modern wind-catchers. In fact this thesis attempts to answer this question as to if it is possible to apply traditional design of wind-catchers to enhance the design of modern wind-catchers. Wind-catchers are vertical towers which are installed above buildings to catch and introduce fresh and cool air into the indoor environment and exhaust inside polluted and hot air to the outside. In order to improve overall efficacy of contemporary wind-catchers the study focuses on the effects of applying vertical louvres, which have been used in traditional systems, and horizontal louvres, which are applied in contemporary wind-catchers. The aims are therefore to compare the performance of these two types of louvres in the system. For this reason, a Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) model was chosen to simulate and study the air movement in and around a wind-catcher when using vertical and horizontal louvres. -

Emancipation Through a Domestic Education: How One Magazine Inspired a Female Literary Renaissance in the Nineteenth-Century Middle East

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current Honors College 5-8-2020 Emancipation through a domestic education: How one magazine inspired a female literary renaissance in the nineteenth-century Middle East Lauren Palmieri Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029 Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons Recommended Citation Palmieri, Lauren, "Emancipation through a domestic education: How one magazine inspired a female literary renaissance in the nineteenth-century Middle East" (2020). Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current. 73. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emancipation Through a Domestic Education: How One Magazine Inspired a Female Literary Renaissance in the Nineteenth-Century Middle East _______________________ An Honors College Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Lauren Samantha Palmieri May 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of History, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors College. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS COLLEGE APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Dr. Timothy J. Fitzgerald, Ph.D., Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Associate Professor, History Dean, Honors College Reader: Dr. Shah Mahmoud Hanifi, Ph.D., Professor, History Reader: Dr. Pia Antolic-Piper, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Philosophy Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... -

Towards the Understanding of Societal Cultures and Leadership

Academic Leadership: The Online Journal Volume 5 Article 19 Issue 3 Fall 2007 10-1-2007 Towards The ndeU rstanding Of Societal Cultures And Leadership In Non-western Countries: An Exploratory Study On Egypt Abdel Moneim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Moneim, Abdel (2007) "Towards The ndeU rstanding Of Societal Cultures And Leadership In Non-western Countries: An Exploratory Study On Egypt," Academic Leadership: The Online Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 3 , Article 19. Available at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj/vol5/iss3/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Leadership: The Online Journal by an authorized editor of FHSU Scholars Repository. academicleadership.org http://www.academicleadership.org/185/towards_the_understand ing_of_societal_cultures_and_leadership_in_non- western_countries_an_exploratory_study_on_egypt/ Academic Leadership Journal INTRODUCTION There has been an increasingly considerable growth of interest in societal culture and leadership in recent years even though there is no shortage of writing on either topic. Numerous papers and books have been written on what they mean and why they are important. These topics have been heavily researched because it is believed that tremendous benefits can be gained when leaders understand the reasons why certain practices and behaviors are successful. More importantly, tremendous benefits can be gained when leaders truly understand the differences in cultures across nations, and incorporate this understanding in current leadership styles. Contemporary thinking has moved rather sharply away from the simple notion that a global measure of leader style could by itself account for any substantial amount of the variance in performance which varies from one country to the other. -

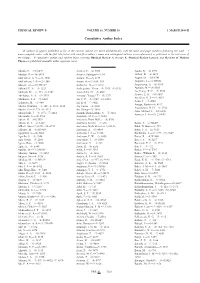

Author Index (Print)

PHYSICAL REVIEW B VOLUME 61, NUMBER 10 1 MARCH 2000-II Cumulative Author Index All authors of papers published so far in the current volume are listed alphabetically with the issue and page numbers following the dash. A more complete index, with the full title listed with each ®rst author's name and subsequent authors cross-referenced, is published in the last issue of the volume. A cumulative author and subject index covering Physical Review A through E, Physical Review Letters, and Reviews of Modern Physics is published annually under separate cover. Abadı´a, C.—͑10͒ 6879 Alvarez, F.—͑2͒ 1083 Astala, R.—͑4͒ 2973 Abadias, G.—͑10͒ 6495 Alvarez, Santiago—͑1͒ 54 Aufray, B.—͑8͒ 5692 Abal’oshev, A. V.—͑2͒ 1500 Amano, H.—͑3͒ 2159 Augier, D.—͑10͒ 6741 Abal’osheva, I. S.—͑2͒ 1500 Amato, A.—͑1͒ 168, 555 Augustin, J.—͑8͒ R5058 Abanov, Ar.—͑10͒ R6467 Ambacher, O.—͑4͒ 2812 Augustsson, A.—͑6͒ 4186 Abboud, K. A.—͑5͒ 3223 Ambegaokar, Vinay—͑5͒ 3555; ͑9͒ 6352 Ausloos, M.—͑8͒ 5303 Abolfath, M.—͑1͒ 343; ͑7͒ 4762 Ammerlahn, D.—͑7͒ 4801 Au Yeung, T. C.—͑9͒ 5920 Abrikosov, A. A.—͑9͒ 5928 Amraoui, Youssef El—͑5͒ 3372 Avanci, L. H.—͑10͒ 6507 ͑ ͒ Abrikosov, I. A.—͑9͒ 6003 An, C. P.—͑6͒ 3989; ͑10͒ 6565 Averkiev, N. S.— 4 3033 Avila, J.—͑7͒ 4948 Acharyya, M.—͑1͒ 464 An, K.-S.—͑7͒ 4621 Awaga, Kunio—͑6͒ 4117 Adachi, Hirohiko—͑1͒ 143; ͑3͒ 1811, 2180 An, Toshu—͑4͒ 3006 Awschalom, D. D.—͑3͒ 1736 Adachi, S.—͑1͒ 778; ͑6͒ 4314 An, Zhong—͑2͒ 1096 Aziz, Michael J.—͑10͒ 6696 Adamowski, J.—͑3͒ 1971; ͑7͒ 4461 Anantha Ramakrishna, S.—͑5͒ 3163 Aznarez, J. -

Newsletter 25

THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ المعھد البريطاني لدراسة العراق NEWSLETTER NO. 25 May 2010 THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ (GERTRUDE BELL MEMORIAL) REGISTERED CHARITY NO. 1135395 & NO. 219948 A company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales No. 6966984 THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ at the British Academy 10, CARLTON HOUSE TERRACE LONDON SW1Y 5AH, UK E-mail: [email protected] Tel. + 44 (0) 20 7969 5274 Fax + 44 (0) 20 7969 5401 Web-site: http://www.bisi.ac.uk The next BISI Newsletter will be published in November 2010. Brief contributions are welcomed on recent research, publications, members’ news and events. They should be sent to BISI by post or e-mail (preferred) to arrive by 15 October 2010. The BISI Administrator Joan Porter MacIver edits the Newsletter. Cover: An etching of a Sumerian cylinder seal impression by Tessa Rickards, which is the cover image of the forthcoming BISI publication, Your Praise is Sweet – A Memorial Volume for Jeremy Black from students, colleagues and friends edited by Heather D. Baker, Eleanor Robson and Gábor Zólyomi (further details p. 32). THE BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ THE BRITISH(GERTRUDE INSTITUTE BELL FOR MEMORIAL) THE STUDY OF IRAQ STATEMENT(GERTRUDE OF BELL PUBLIC MEMORIAL) BENEFIT STATEMENT OF PUBLIC BENEFIT ‘To advance research and public education relating to Iraq and the neighbouring‘To advance countriesresearch inand anthropology, public education archaeology, relating geography,to Iraq and history, the languageneighbouring and countriesrelated disciplines in anthropology, within archaeology,the arts, humanities geography, and history, social sciences.’language and related disciplines within the arts, humanities and social sciences.’ • BISI supports high-quality research across its academic remit by • makingBISI supports grants and high-quality providing expertresearch advice across and itsinput.