Transit and Urban Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 5 Station Descriptions And

Appendix 5 Station Descriptions and Technical Overview Stage 2 light rail transit (LRT) stations will follow the same standards, design principles, and connectivity and mobility requirements as Stage 1 Confederation Line. Proponent Teams were instructed, through the guidelines outlined in the Project Agreement (PA), to design stations that will integrate with Stage 1, which include customer facilities, accessibility features, and the ability to support the City’s Transportation Master Plan (TMP) goals for public transit and ridership growth. The station features planned for the Stage 2 LRT Project will be designed and built on these performance standards which include: Barrier-free path of travel to entrances of stations; Accessible fare gates at each entrance, providing easy access for customers using mobility devices or service animals; Tactile wayfinding tiles will trace the accessible route through the fare gates, to elevators, platforms and exits; Transecure waiting areas on the train platform will include accessible benches and tactile/Braille signs indicating the direction of service; Tactile warning strips and inter-car barriers to keep everyone safely away from the platform edge; Audio announcements and visual displays for waiting passengers will precede each train’s arrival on the platform and will describe the direction of travel; Service alerts will be shown visually on the passenger information display monitors and announced audibly on the public-address system; All wayfinding and safety signage will be provided following the applicable accessibility standards (including type size, tactile signage, and appropriate colour contrast); Clear, open sight lines and pedestrian design that make wayfinding simple and intuitive; and, Cycling facilities at all stations including shelter for 80 per cent of the provided spaces, with additional space protected to ensure cycling facilities can be doubled and integrated into the station’s footprint. -

Urban and Historic Context

Architectural Rejuvenation Project URBAN AND HISTORIC CONTEXT Barry Padolsky Associates Inc., Architects, Urban Design and Heritage Consultants February 13, 2015 Aerial view of National Arts Centre (2010) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................................2 Urban and Historic Context........................................................................................................2 . The Holt/Bennett Plan ................................................................................................................4 The Gréber Plan .........................................................................................................................6 The Parkin Plan ...........................................................................................................................8 Architecture and National Identity: the Centennial Projects .......................................................9 NAC: The Architectural Challenge ............................................................................................10 The Architectural Response .....................................................................................................13 Architectural Style: Polite “Brutalism” ......................................................................................16 Re-inventing “Brutalism”..........................................................................................................17 NCC Canada’s -

2. Faqs__Transit Service During Confed Line

Transit Service During Confederation Line Construction – Updates for 2016 REPORT TRANSIT SERVICES DEPARTMENT REPORT FAQs REPORT Transit Service During Confederation Line Construction – Updates for 2016 TITLE DIVISION: Customer Systems and Planning BRANCH Service Planning REPORT Pat Scrimgeour, Assistant General Manager, Customer Date: January 26, 2016 AUTHOR Systems and Planning SCHEDULED DATES FOR REPORT GM’s REVIEW OF REPORT TRANSIT COMMISSION COUNCIL January 19, 2016 February 17, 2016 N/A Q1. How long will the Confederation Line construction service adjustments last for? What are the next phases for service adjustments? A1. The O-Train Confederation Line is scheduled to open in 2018. Service adjustments will take place in sequential phases as sections of the Transitway undergo construction work. Each section of Transitway that closes for conversion to light rail will never reopen for bus operations. The remaining Transitway closures are: • April 2016 – Laurier Station to Lees Station; and • June 2016 – Tunney's Pasture Station to Merton Street. Timelines will be updated as information becomes available. Service adjustment plans will be implemented as these closures take effect. Stations will remain open during the construction period, with the exceptions of Cyrville Station, which was closed in June 2015, and Campus Station, which will close in April 2016. Q2. What are the main highlights of upcoming transit service adjustments during Confederation Line Construction? A2. The following are the main highlights of upcoming transit service adjustments during O- Train Confederation Line Construction: • On April 24, 2016, the Transitway will close between Laurier Station and Lees Station. Most transit service along this section of the Transitway will be relocated to Nicholas Street and Highway 417, using the bus-only lanes that have been built for this purpose. -

Top Local Titles What Makes West Coasters Tick? Find out Through This Eclectic Selection of Recent Releases, Available at Local Bookstores (Page 31).—Sheri Radford

Shopping Top Local Titles What makes West Coasters tick? Find out through this eclectic selection of recent releases, available at local bookstores (page 31).—Sheri Radford A Taste of Haida Gwaii: Raincoast Chronicles Remake: Master Works Those Girls by Chevy Food Gathering and 23 edited by Peter of Art Reimagined Stevens (St. Martin’s Feasting at the Edge A. Robson (Harbour by Jeff Hamada Press; $21.99): In her of the World by Susan Publishing; $24.95): (Chronicle Books; fifth novel, the New Musgrave (Whitecap It’s not a journal. It’s $33.95): Imagine iconic York Times best-selling Books; $34.95): One not a book. So what is works of art given a author (and Vancouver of Canada’s most it, exactly? Over the do-over by modern- Island resident) weaves celebrated poets has past four decades, the day artists. That’s the another page-turner of created her first cook- Raincoast Chronicles premise behind this a tale set in small-town book, packed full of series has brought to crowd-sourced col- British Columbia, this lyrical prose, stunning life the assortment of lection, curated by time about three sis- colour photographs, oddball characters and the Vancouverite who ters on the run who are and seasonal recipes bizarre events that give founded the art blog forced to confront their using fresh West Canada’s West Coast Booooooom (www. past—and, perhaps, Coast ingredients. its unique flavour. booooooom.com). exact revenge. 604-687-5233. www.jademine.com SILVER GALLERY This Native jewel- 604-660-4570. X Map 1: B3 768 Map 1: B7 lery dealer has cornered the silver Bute St. -

Project Synopsis

Final Draft Road Network Development Report Submitted to the City of Ottawa by IBI Group September 2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Approach ............................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Report Structure .................................................................................................. 3 2. Background Information ...................................................................... 4 2.1 The TRANS Screenline System ......................................................................... 4 2.2 The TRANS Forecasting Model ......................................................................... 4 2.3 The 2008 Transportation Master Plan ............................................................... 7 2.4 Progress Since 2008 ........................................................................................... 9 Community Design Plans and Other Studies ................................................................. 9 Environmental Assessments ........................................................................................ 10 Approvals and Construction .......................................................................................... 10 3. Needs and Opportunities .................................................................. -

Kanata Light Rail Transit Planning and Environmental Assessment Study (Moodie Drive to Hazeldean Road) – Recommendations

1 Report to Rapport au: Transportation Committee Comité des transports 2 May 2018 / 2 mai 2018 and Council et au Conseil 9 May 2018 / 9 mai 2018 Submitted on April 17, 2018 Soumis le 17 avril 2018 Submitted by Soumis par: John Manconi, General Manager / Directeur général, Transportation Services Department / Direction générale des transports Contact Person Personne ressource: Vivi Chi, Director / Directeur, Transportation Planning / Planification des transports, Transportation Services Department / Direction générale des transports (613) 580-2424, 21877, [email protected] Ward: KANATA NORTH (4) / KANATA File Number: ACS2018-TSD-PLN-0002 NORD (4) / STITTSVILLE (6) / BAY (7) / BAIE (7) / COLLEGE (8) / COLLÈGE (8) / KANATA SOUTH (23) / KANATA-SUD (23) SUBJECT: Kanata Light Rail Transit Planning and Environmental Assessment Study (Moodie Drive to Hazeldean Road) – Recommendations OBJET: Étude de planification et d’évaluation environnementale du Train léger sur rail proposé vers Kanata (de la promenade Moodie au chemin Hazeldean) – Recommandations 2 REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS That Transportation Committee recommend that Council: 1. Approve the functional design for the Kanata Light Rail Transit (Moodie Drive to Hazeldean Road), as described in this report and supporting documents one and two; and, 2. Direct Transportation Planning staff to initiate the Transit Project Assessment Process in accordance with the Ontario Environmental Assessment Act (Regulation 231/08), including the preparation and filing of the Environmental Project Report for final public review and comment. RECOMMANDATIONS DU RAPPORT Que le Comité des transports recommande au Conseil : 1. d’approuver la conception fonctionnelle du Train léger sur rail vers Kanata (de la promenade Moodie au chemin Hazeldean), comme présentée dans le présent rapport et dans les documents un à deux; et, 2. -

2019 City Wide Development Charges Background Study

2019 City-Wide Development Charges Background Study Version for Public Consultation HEMSON C o n s u l t i n g L t d. March 15, 2019 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .......................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 2 A. Purpose of 2019 Development Charges (DC) Background Study .. 2 B. City-Wide and Area-Specific DCs Have Been Calculated ............... 3 C. Development Forecast .................................................................... 4 D. Public Transit Ridership Forecast ................................................... 5 E. Calculated Development Charges .................................................. 5 F. Cost of Growth Analysis .................................................................. 6 G. Development Charges Administration & Policy Considerations ...... 7 I Purpose of 2019 Development Charges Background Study ............. 8 A. Introduction and Background .......................................................... 8 B. Legislative Context .......................................................................... 9 C. The 2019 DC Study is Intended to be an Interim Update ................ 9 D. Consultation And Approval Process ................................................ 9 E. Key Steps In Determining DCs for Future Development-Related Projects ......................................................................................... 10 F. Long-Term Capital -

No. 48, Port Lands Flood Protection and Enabling Infrastructure, Page 54 Credit: Waterfront Toronto/Vid Ingelevics/Ryan Walker

2021 No. 48, Port Lands Flood Protection and Enabling Infrastructure, Page 54 Credit: Waterfront Toronto/Vid Ingelevics/Ryan Walker Top100 Projects 2021 Changing the Language of Top100 Projects — 2021 An annual report inserted in Infrastructure ReNew Canada’s had an interesting encounter following the release of last January/February 2021 issue year’s report, and I wanted to share in an effort to get I feedback from the rest of the industry. MANAGING Andrew Macklin We had released the 2020 Top100 Projects report and were EDITOR [email protected] getting set for the Key Players and Owners Dinner, which we host every February in Toronto as a celebration of the accomplishments GROUP Todd Latham PUBLISHER of the industry in developing infrastructure megaprojects. I had heard through one of my colleagues that a couple of well-respected PUBLISHER Nick Krukowski members of the industry wanted to chat with me at the event and I should seek them out. So I did. ART DIRECTOR AND Donna Endacott SENIOR DESIGN My first thought was that, not having nearly the expertise as many of you, that I had somehow managed to royally screw something ASSOCIATE Simran Chattha up. Or perhaps they wanted to tell me that I should try a different EDITOR tact to the report? Maybe a new idea for adding a complementary DIGITAL MARKETING Becky Umweni piece for this report? But as it turned out, they wanted to have a COORDINATOR conversation with me about… language. DIGITAL The language of this report has become, to some, quite convoluted. Connie Vitello EDITOR As different jurisdictions use the language familiar to them, it can often mean that, from one project to the next, different words are EVENT Natasha Mawji MANAGER used to describe the same thing. -

Ottawa Transportation Report.Pdf

OTTAWA THE IMPACT OF TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENTS ON HOUSING VALUES IN THE OTTAWA REGION Don R Campbell, Senior Analyst Melanie Reuter, Director of Research Allyssa Epp, Research Analyst WWW.REINCANADA.COM AUTHORS Don R. Campbell, Senior Analyst, REIN Ltd Melanie Reuter, Director of Research, REIN Ltd Allyssa Fischer, Research Analyst, REIN Ltd © The Real Estate Investment Network Ltd. 6 – 27250 58 Cr Langley, BC V4W 3W7 Tel (604) 856-2825 Fax (604) 856-0091 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Page: www.reincanada.com Important Disclaimer: This Report, or any seminars or updates given in relation thereto, is sold, or otherwise provided, on the understanding that the authors – Don R. Campbell, Melanie Reuter, Allyssa Fischer, and The Real Estate Investment Network Ltd and their instructors, are not responsible for any results or results of any actions taken in reliance upon any information contained in this report, or conveyed by way of the said seminars, nor for any errors contained therein or presented thereat or omissions in relation thereto. It is further understood that the said authors and instructors do not purport to render legal, accounting, tax, investment, financial planning or other professional advice. The said authors and instructors hereby disclaim all and any liability to any person, whether a purchaser of this Report, a student of the said seminars, or otherwise, arising in respect of this Report, or the said seminars, and of the consequences of anything done or purported to be done by any such person in reliance, whether in whole or part, upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Report or the said seminars. -

Lloyd Urban Village (LUV), NAIOP Workshop Project

Portland State University PDXScholar Real Estate Development Workshop Projects Center for Real Estate Summer 2019 Lloyd Urban Village (LUV), NAIOP Workshop Project Shellee McCullick Portland State University Cait Olds Portland State University Eriko Shimada Portland State University Damon Tidwell Portland State University Eric Zechenelly Portland State University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/realestate_workshop Part of the Real Estate Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McCullick, Shellee; Olds, Cait; Shimada, Eriko; Tidwell, Damon; Zechenelly, Eric; and Zhao, Nikki, "Lloyd Urban Village (LUV), NAIOP Workshop Project" (2019). Real Estate Development Workshop Projects. 27. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/realestate_workshop/27 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Real Estate Development Workshop Projects by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Shellee McCullick, Cait Olds, Eriko Shimada, Damon Tidwell, Eric Zechenelly, and Nikki Zhao This report is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/realestate_workshop/27 L U V 1 Lloyd Urban Village Presented By: Portland State University, Master of Real Estate Development, August 2019 Team: Shellee McCullick, Caitlyn Olds, Eriko Shimada, Damon Tidwell, Eric Zechenelly, Yu Zhao 2 Vision Imagine being at the forefront of a 1.5 million square foot mixed-use development in the heart of Portland’s newest entertainment district. Imagine a superblock development that becomes a destination for all of Portland to live, work and play. -

Recommended Plan.Pdf

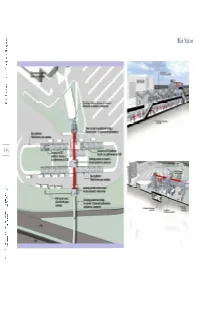

Blair Station 9-34 Maintenance and Storage Facility Track redundancy within the facility will be provided to ensure The proposed Maintenance and Storage Facility is an integral the ability to move LRVs under vehicle or system failure part of the project, as it will: conditions. • House and service all of the trains needed to operate the The preferred site for the Maintenance and Storage Facility has line been determined based on the following criteria: • Service vehicles to be used on future LRT lines • Site Characteristics (topography, grade, land use compatibility, expansion capability and environmental • House the operations control centre (signalling, considerations) communications) for the line • Facility Operations (turnaround loops, track redundancy, • Be the primary heavy maintenance facility for the LRT layout efficiency and municipal services) network Maintenance of the LRVs is crucial to maintain vehicle • System Operations (connectivity to the line, efficiency and manufacturer's warranties, minimize long term operating costs access to freight rail), and and provide for system safety and reliability. The Maintenance • Relative Costs (capital, operating, maintenance and and Storage Facility will accommodate the following elements property ownership and acquisition) on-site: The proposed Maintenance and Storage Facility for the DOTT 9-35 • Main facility building housing offices, roster areas, meeting project will be located on lands to the west of the existing OC rooms and control equipment Transpo headquarters and bus maintenance facility located on • Storage yard for regular cleaning and minor maintenance the north side of Belfast Road, west of St. Laurent Boulevard and south of the VIA rail corridor. In order to access this • Repair areas for heavy and light maintenance areas for location, a connecting track is required between the DOTT vehicles alignment and the Maintenance and Storage Facility. -

1 Report to Rapport Au

1 Report to Rapport au: Transit Commission Commission du transport en commun 19 June 2019 / 19 juin 2019 Submitted on June 10, 2019 Soumis le 10 juin 2019 Submitted by Soumis par: John Manconi, General Manager / Directeur général, Transportation Services Department / Direction générale des transports Contact Person Personne ressource: John Manconi, General Manager / Directeur général Transportation Services Department / Direction générale des transports 613-580-2424 ext./poste 52111, [email protected] Ward: CITY WIDE / À L'ÉCHELLE DE LA File Number: ACS2019-TSD-TS-0002 VILLE SUBJECT: Confederation Line: Customer Service Operational Readiness OBJET: Ligne de la Confédération : Préparation opérationnelle du service à la clientèle REPORT RECOMMENDATION That the Transit Commission receive this report for information. RECOMMANDATION DU RAPPORT Que la Commission du transport en commun prenne connaissance de ce rapport. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The opening of O-Train Line 1, the Confederation Line, will mark an exciting and historic transformation in the way transit service is delivered in the city of Ottawa. OC Transpo has been working with the Rideau Transit Group (RTG) and partners from across the city to transform the current transit service into a world-class multimodal transit system and ensure a positive end-to-end customer experience starting on day one. The opening of Line 1 and the major changes to the bus route network that will follow, will be the largest service change ever for OC Transpo customers. Because our customers are our priority and their experience through and beyond this transitional period is important to us, OC Transpo staff are committed to ensuring that customers are prepared, comfortable and knowledgeable about these changes and the transition period in which they will occur.