Health Assessment for Tajikistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Cross-Border Conflict in Post-Soviet Central Asia: the Case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

Connections: The Quarterly Journal ISSN 1812-1098, e-ISSN 1812-2973 Toktomushev, Connections QJ 17, no. 1 (2018): 21-41 https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.17.1.02 Research Article Understanding Cross-Border Conflict in Post-Soviet Central Asia: The Case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Kemel Toktomushev University of Central Asia, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, http://www.ucentralasia.org Abstract: Despite the prevalence of works on the ‘discourses of danger’ in the Ferghana Valley, which re-invented post-Soviet Central Asia as a site of intervention, the literature on the conflict potential in the cross-border areas of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan is fairly limited. Yet, the number of small-scale clashes and tensions on the borders of the Batken and Isfara regions has been growing steadily. Accordingly, this work seeks to con- tribute to the understanding of the conflict escalations in the area and identify factors that aggravate tensions between the communities. In par- ticular, this article focuses on four variables, which exacerbate tensions and hinder the restoration of a peaceful social fabric in the Batken-Isfara region: the unresolved legacies of the Soviet past, inefficient use of natu- ral resources, militarization of borders, and lack of evidence-based poli- cymaking. Keywords: Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Ferghana, conflict, bor- ders. Introduction The significance and magnitude of violence and conflict potential in the con- temporary Ferghana Valley has been identified as one of the most prevalent themes in the study of post-Soviet Central Asia. This densely populated region has been long portrayed as a site of latent inter-ethnic conflict. Not only is the Ferghana Valley a region, where three major ethnic groups—Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks—co-exist in a network of interdependent communities, sharing buri- Partnership for Peace Consortium of Defense Creative Commons Academies and Security Studies Institutes BY-NC-SA 4.0 Kemel Toktomushev, Connections QJ 17, no. -

Tajikistan 2013 Human Rights Report

TAJIKISTAN 2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tajikistan is an authoritarian state that President Emomali Rahmon and his supporters, drawn mainly from one region of the country, dominated politically. The constitution provides for a multi-party political system, but the government obstructed political pluralism. The November 6 presidential election lacked pluralism, genuine choice, and did not meet international standards. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. The most significant human rights problems included torture and abuse of detainees and other persons by security forces; repression of political activism and restrictions on freedoms of expression and the free flow of information, including the repeated blockage of several independent news and social networking websites; and poor religious freedom conditions as well as violence and discrimination against women. Other human rights problems included arbitrary arrest; denial of the right to a fair trial; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; prohibition of international monitor access to prisons; limitations on children’s religious education; corruption; and trafficking in persons, including sex and labor trafficking. Officials in the security services and elsewhere in the government acted with impunity. There were very few prosecutions of government officials for human rights abuses. The courts convicted one prison official for abuse of power, and three others were under investigation for human rights abuses. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life In July and August 2012, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the media reported that the government or its agents were responsible for injuring and killing civilians during security operations in Khorugh, Gorno-Badakhshon Autonomous Oblast (GBAO), after the killing of Major General Abdullo Nazarov, the head of the regional branch of the State Committee for National Security (GKNB). -

Central Asia the Caucasus

CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS No. 2(44), 2007 CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS Journal of Social and Political Studies 2(44) 2007 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 1 No. 2(44), 2007FOUNDED AND PUBLISHEDCENTRAL ASIA AND BYTHE CAUCASUS INSTITUTE INSTITUTE O OR CENTRAL ASIAN AND STRATEGIC STUDIES O CAUCASIAN STUDIES THE CAUCASUS Registration number: 620720-0459 Registration number: M-770 State Administration for Ministry of Justice of Patents and Registration of Sweden Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press®. SWEDEN Registration number: 556699-5964 Journal registration number: 23 614 State Administration for Patents and Registration of Sweden E d i t o r i a l C o u n c i l Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council ISMAILOV Tel./fax: (994 - 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Murad ESENOV Editor-in-Chief Tel./fax: (46) 920 62016 E-mail: [email protected] Jannatkhan Executive Secretary (Baku, Azerbaijan) EYVAZOV Tel./fax: (994 - 12) 499 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Timur represents the journal in Kazakhstan (Astana) SHAYMERGENOV Tel./fax: (+7 - 701) 531 61 46 E-mail: [email protected] Leonid represents the journal in Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek) BONDARETS Tel.: (+996 - 312) 65-48-33 E-mail: [email protected] Jamila MAJIDOVA represents the journal in Tajikistan (Dushanbe) Tel.: (992 - 917) 72 81 79 E-mail: [email protected] Farkhad represents the journal in Uzbekistan (Tashkent) TOLIPOV Tel.: (9987-1) 125 43 22 E-mail: [email protected] Aghasi YENOKIAN represents the journal in Armenia (Erevan) Tel.: (374 - 1) 54 10 22 E-mail: [email protected] -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized Nurek Hydropower Rehabilitation Project Phase 2 Republic of Tajikistan

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized Nurek Hydropower Rehabilitation Project Phase 2 Republic of Tajikistan May 2020 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Nurek HPP Rehabilitation Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the ESIA ............................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Organization of the ESIA ....................................................................................................... 3 2 Project description .......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Description of Nurek HPP ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 The Project ............................................................................................................................ 7 Dam Safety ............................................................................................................... 9 Details of work to be performed ............................................................................. 9 Refurbishment -

Misuse of Licit Trade for Opiate Trafficking in Western and Central

MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA A Threat Assessment A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2012 MISUSE OF LICIT TRADE FOR OPIATE TRAFFICKING IN WESTERN AND CENTRAL ASIA Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), within the framework of UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and in Pakistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions that shared their knowledge and data with the report team including, in particular, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, the customs offices of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the World Customs Office, the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre, the Customs Service of Tajikistan, the Drug Control Agency of Tajikistan and the State Service on Drug Control of Kyrgyzstan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Programme management officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Natascha Eichinger (Consultant) Platon Nozadze (Consultant) Hayder Mili (Research expert, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Yekaterina Spassova (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Hamid Azizi (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Shaukat Ullah Khan (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) A. -

Analysis of the Situation on Inclusive Education for People with Disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the Results of the Baseline Research

Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok» April - July 2018 Analysis of the situation on inclusive education for people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan Report on the results of the baseline research 1 EXPRESSION OF APPRECIATION A basic study on the inclusive education of people with disabilities in the Republic of Tajikistan (RT) conducted by the Public Organization Disabled Women's League “Ishtirok”. This study was conducted under financial support from ASIA SOUTH PACIFIC ASSOCIATION FOR BASIC AND ADULT EDUCATION (ASPBAE) The research team expresses special thanks to the Executive Office of the President of the RT for assistance in collecting data at the national, regional, and district levels. In addition, we express our gratitude for the timely provision of data to the Centre for adult education of Tajikistan of the Ministry of labor, migration, and employment of population of RT, the Ministry of education and science of RT. We express our deep gratitude to all public organizations, departments of social protection and education in the cities of Dushanbe, Bokhtar, Khujand, Konibodom, and Vahdat. Moreover, we are grateful to all parents of children with disabilities, secondary school teachers, teachers of primary and secondary vocational education, who have made a significant contribution to the collection of high-quality data on the development of the situation of inclusive education for persons with disabilities in the country. Research team: Saida Inoyatova – coordinator, director, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Salomat Asoeva – Assistant Coordinator, Public Organization - League of women with disabilities «Ishtirok»; Larisa Alexandrova – lawyer, director of the Public Foundation “Your Choice”; Margarita Khegay – socio-economist, candidate of economic sciences. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

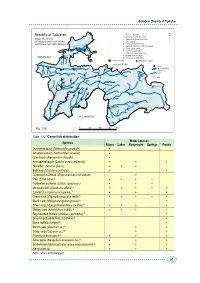

Biological Diversity of Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan The Legend: 1 - Acipenser nudiventris Lovet 2 - Salmo trutta morfa fario Linne ya 3 - A.a.a. (Linne) ar rd Sy 4 - Ctenopharyngodon idella Kayrakkum reservoir 5 - Hypophthalmichtus molitrix (Valenea) Khujand 6 - Silurus glanis Linne 7 - Cyprinus carpio Linne a r a 8 - Lucioperca lucioperea Linne f s Dagano-Say I 9 - Abramis brama (Linne) reservoir UZBEKISTAN 10 -Carassus auratus gibilio Katasay reservoir economical pond distribution location KYRGYZSTAN cities Zeravshan lakes and water reservoirs Yagnob rivers Muksu ob Iskanderkul Lake Surkh o CHINA b r Karakul Lake o S b gou o in h l z ik r b e a O b V y u k Dushanbe o ir K Rangul Lake o rv Shorkul Lake e P ch z a n e n a r j V ek em Nur gul Murg u az ab s Y h k a Y u ng Sarez Lake s l ta i r a u iz s B ir K Kulyab o T Kurgan-Tube n a g i n r Gunt i Yashilkul Lake f h a s K h Khorog k a Zorkul Lake V Turumtaikul Lake ra P a an d j kh Sha A AFGHANISTAN m u da rya nj a P Fig. 1.16. 0 50 100 150 Km Table 1.12. Game fish distribution Water sources Species Rivers Lakes Reservoirs Springs Ponds Dushanbe loach (Nemachilus pardalis) + Amudarya loach (Nemachilus oxianus) + Gray loach (Nemachilus dorsalis) + Aral spined loach (Cobitis aurata aralensis) + + + Sheatfish (Sclurus glanis) + + + Bullhead (Ictalurus punctata) А + + Turkestan bullhead (Glyptosternum reticulatum) + Pike (Esox lucius) + + + + Turkestan bullhead (Cottus spinolosus) + + + Mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) А + + + + + Zander (Lucioperca lucioperea) А + + + Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon della) А + + + + + Black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) А + Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthus molitrix) А + + + + Motley carp (Aristichthus nobilis) А + + + + Big-mouthed buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) А + Small-mouthed buffalo (I.bufalus) А + Black buffalo (I.niger) А + Mirror carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Scaly carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Pseudorasbora parva А + + + Amur goby (Neogobius amurensis sp.) А + + + Snakehead (Ophiocephalus argus warpachowski) А + + + Hemiculter sp. -

LITACA-II MTE Final Report.Pdf

Mid-Term Evaluation Report Livelihood Improvement in Tajik – Afghan Cross Border Areas (LITACA-II) Report Information Report Title: Mid-Term Evaluation of Livelihood Improvement in Tajik- Afghan Cross-Border Areas; LITACA Phase II (2018 – 2020) Evaluation Team: Dilli Joshi, Independent Evaluation Specialist Ilhomjon Aliev, National Evaluation Specialist Field Mission: 4–29 February, 2020 Table of Contents Abbreviations Executive summary .............................................................................................................................. i 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 LITACA-II Goals, outcomes and outputs ........................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Theory of Change ..................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Objectives of the LITACA-II Mid-Term Evaluation ......................................................... 5 1.4 Purpose of the Mid-Term Evaluation ................................................................................. 5 1.5 Scope of the Mid-Term Evaluation ...................................................................................... 5 1.6 Organisation of the Mid-Term Evaluation ......................................................................... 5 2. Evaluation Approach and Methodology.................................................................................