Chapter 6. Kiribati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 97 TABLE 1

Pacific Islands - Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 97 Country Name: Kiribati TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall Station (include data period) September 2015 July August Total 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking 2015 2015 Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall (mm) Total Total (mm) (mm) Kanton 224 165.8 - 20.1 51.5 40.0 - Kiritimati 417.3 171.7 124.9 4.0 15.4 8.0 81 Tarawa 171.9 233.1 358.5 55.1 142.8 84.3 64 Butaritari 87.8 176.7 178.6 113.3 177.3 136 52 Beru 135.8 - - 28.1 68.0 43.3 - TABLE 2: Three-monthly Rainfall July to September 2015 [Please note that the data used in this verification should be sourced from table 3 of OCOF #93] Station Three-month 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking Forecast probs.* Verification * Total Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall (include LEPS) (Consistent, (mm) (mm) (mm) Near- consistent Inconsistent? Kanton - 138.2 219.0 170.9 - 17/ 43 /40 (0.7) - Kiritimati 713.9 42.6 101.3 72.1 88/88 26/29/ 45 (-0.1) Consistent Tarawa 763.5 195.8 543.6 335.0 56/66 6/14/ 80 (19.7) Consistent Butaritari 443.1 506.3 743.0 634.0 16/73 5/35/ 60 (13.5) Inconsistent Beru - 130.7 292.5 173.5 - 3/13/ 84 (23.8) - Period:* below normal /normal /above normal Predictors and Period used for July to September 2015 Outlooks (refer to OCOF #93): Nino 3.4 SST Anomalies extended (2mths) * Forecast is consistent when observed and predicted (tercile with the highest probability) categories coincide (are in the same tercile). -

Kiritimati and Malden, Kiribati, Nuclear Weapons Test Sites

Kiritimati and Malden, Kiribati, Nuclear weapons test sites A total of 33 nuclear detonations were conducted on two atolls of the Republic of Kiribati by the UK and the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s. Thousands of islanders and servicemen were subjected to radioactive fallout and now su er from radiation e ects. History The Pacifi c atoll of Kiritimati (formerly the British colo- ny “Christmas Island”), served during WWII as a stop- over for the U.S. Air Force on its way to Japan. After the war, the United Kingdom used the atolls for its fi rst series of fi ssion bomb explosions. Due to agree- ments made with the Australian government, these servicemen and the indigenous population were free explosions could not be conducted at the British nu- to move around the island, consuming local water and clear testing site at Maralinga. On May 15, 1957, the fruits, bathing in contaminated lagoons and breathing fi rst British hydrogen bomb, code-named “Operation in radioactive dust.1 Grapple,” was exploded off the coast of Malden, fol- In 2006, 300 former Christmas Island residents sub- lowed by another a month later, neither of which yield- mitted a petition to the European Parliament, accus- ed the explosive power that was expected. The tests ing the UK of knowingly exposing them to radioactive reached a maximum yield of 720 kilotons, equivalent fallout despite knowing of the dangers. Declassifi ed to more than 50 times the power of the bomb that was government documents from the time warned that ra- dropped on Hiroshima. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

Kiribati National Biodiversity Strategies and Actions Plan 2005 NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS PLAN (KIRITIMATI ISLAND 2005) PREPARED BY ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION DIVISION MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, LANDS AND AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT October, 2006. 1En vironment & Conservation Division- MELAD Kiribati National Biodiversity Strategies and Actions Plan 2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Biodiversity in this context means all terrestrial and marine ecosystems, all plants and animal species and varieties found in these ecosystems including the knowledge, uses, beliefs and language that the people of Kiribati have in relation to their ecosystems and species. Biodiversity Conservation is always considered along with sustainable use. It has been confirmed that the present state of biodiversity in the Republic of Kiribati is being degraded socially, economically, politically and even judicially. As a nation with very limited resources we just cannot afford to sit back and let this serious degradation continues. If the biodiversity is not conserved or used on a sustainable basis, and if traditional sustainable management practices, and the knowledge and relevant language are not maintained or strengthened then future development would not be able to sustain the people in the long term. The main key in the whole process is the resource owners and users at the community level who hold the long- lasting key to biodiversity conservation. The development of Kiribati National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (K-NBSAP) has been highly consultative. The process of collecting data and information has been guided by the Steering Committee, a multi-disciplinary committee that comprises of representatives from different stakeholders. The diverse representation of the Steering Committee and the collaborative incentive of the grassroots people reflected a shift towards a multi-sectoral collaboration and the need to establish stronger social and institutional infrastructure to make local community co-management actually work in practice. -

Habitat Use and Status of the Bokikokiko Or Christmas Island Warbler (Acrocephalus Aequinoctialis)1

Habitat Use and Status of the Bokikokiko or Christmas Island Warbler (Acrocephalus aequinoctialis)1 Eric A. VanderWerf,2,5 Ray Pierce,3 Ratita Bebe,4 and Katareti Taabu4 Abstract: The Bokikokiko or Christmas Island Warbler (Acrocephalus aequinoc tialis) is found only on Kiritimati (Christmas) and Teraina ( Washington) Islands in the Republic of Kiribati. The population on Kiritimati Island is threatened by habitat degradation, sea level rise, and predation from feral cats (Felis catus), Pa- cific rats Rattus( exulans), and recently arrived black rats (Rattus rattus). There is scant information about distribution and abundance of the Bokikokiko. From 2007 to 2012, we conducted surveys with song playbacks at 83 points on 12 tran- sects in the northern half of Kiritimati Island to measure abundance of the Bokikokiko and begin monitoring for possible declines associated with the spread of rats, and we collected habitat data to investigate factors that influenced Bokikokiko abundance. Song playbacks resulted in a 263% increase in detection rate over passive listening. We detected an average (±1 SE) of 0.63 ± 0.11 birds per point using playbacks. Average population density was 0.36 ± 0.06 birds per hectare, but abundance varied among regions, and no birds were detected in some areas with apparently suitable habitat. Range of the Bokikokiko encom- passed an area of 14,180 ha but was fragmented by many lagoons and bare ground, and only about half that area was actually occupied. Estimated popula- tion size was 2,550 ± 425 birds. Bokikokiko were more abundant in areas with taller Heliotropium trees and taller Scaevola shrubs, and less abundant in areas with more Suriana shrubs, bare ground, and grass. -

Kiribati Background Information

Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................................................... i List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................... iii 1.0. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Kiribati Background Information ............................................................................................................. 2 3.0 Biodiversity in Kiribati ............................................................................................................................. 3 4.0 Analysis of the Causes and Consequences of Biodiversity Loss ............................................................. 6 4.1 Causes of Biodiversity Loss ................................................................................................................. 6 4.2 Consequences of Biodiversity Loss ...................................................................................................... 8 5.0 National, Constitutional, Legal and Institutional Framework .................................................................. 8 5.1 Legislation ............................................................................................................................................ 8 5.2 Relevant Policies and Plans ............................................................................................................... -

Cepf Final Project Completion Report

CEPF FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Organization Legal Name: Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme Holding the Lines — Restoration of the Northern Line Project Title: Islands, Kiribati Date of Report: 28 February, 2013 Report Author and Contact Posa A. Skelton – [email protected] Information Dr Ray Pierce, Dr Souad Boudjelas, Dr Alan Tye, Seema Report contributors Deo, Ratita Bebe CEPF Region: Polynesia-Micronesia Strategic Direction: 1. Prevent, control, and eradicate invasive species in key biodiversity areas Grant Amount USD$ 165,000 Project Dates: October 1, 2009-December 31, 2012 Te Io – Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus) roosting on shrubs on Motu Tabu – a predator free island and a conservation area for seabirds Implementation Partners for this Project (please explain the level of involvement for each partner): Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme – provided the coordination for the project, including liaising between the Wildlife Conservation Unit (Govt. Kiribati) and technical experts (especially the Pacific Invasives Partnership). Also contributed technical advice and expertise in various activities of the project. Facilitated and assisted with development of awareness resources and also drafting of reports. Provided guidance and mentoring support to Wildlife Conservation Unit staff. Provided financial assistance and supported the participation and building of the capacity of the WCU staff in regional training courses and workshops. Ministry of Environment, Land and Agricultural Development – Wildlife Conservation Unit (Government of Kiribati) – provided support and co-financing in the implementation of activities of the project. Lead on the ground activities and actions and also provided the reality check of project activities and components. Provided dedicated staff to assist with the various project activities. -

Kiribati.Pdf

II. Situation Analysis and Agriculture Sector Overview 2.1 Kiribati is as an atoll nation spread over some 3.5 million square kilometres of the Pacific Ocean. Physically, it has some of the world’s smallest islets, but also has - in Kiritimati (Christmas Island) - the world’s largest atoll. The nation is facing numerous economic, social, demographic and environmental challenges, but the greatest challenge is the tyranny of distance. The country has limited natural resources and, for those natural resources it does possess (e.g. fisheries), insufficient capacity to exploit them for maximum national benefit. GDP per capita is the lowest amongst the Pacific Island Forum group and the economic outlook is fragile. With limited exports and rising costs of imports the country runs a deep 16 trade deficit . The heavy dependence on imported staple foods (such as rice and flour), coupled with soaring global food prices is posing a serious threat to both food and nutrition security. Average annual household income is about A$8,700 and an estimated 46 per cent 17 is spent on food, which constitutes the single largest expenditure group . Increased urbanization on South Tarawa due to migration of population from the outer islands is accentuating social issues and environmental problems. A high priority for government therefore is to provide sustainable livelihood opportunities on the outer islands. Government is encouraging outer island growth focused on Kiritimati, with the objective of locating up to 20,000 people on the island. As a low low-lying atoll nation, adaptation to the impacts of climate change is being mainstreamed into national development policy. -

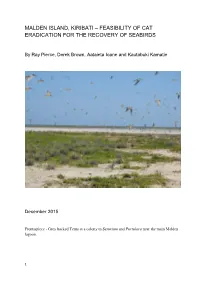

Malden Island, Kiribati – Feasibility of Cat Eradication for the Recovery of Seabirds

MALDEN ISLAND, KIRIBATI – FEASIBILITY OF CAT ERADICATION FOR THE RECOVERY OF SEABIRDS By Ray Pierce, Derek Brown, Aataieta Ioane and Kautabuki Kamatie December 2015 Frontispiece - Grey backed Terns at a colony in Sesuvium and Portulaca near the main Malden lagoon. 1 CONTENTS MAP OF KIRIBATI 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 ACRONYMS AND KEY DEFIMITIONS 4 MAP OF MALDEN 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF MALDEN ISLAND 5 2.1 Geology and landforms 5 2.2 Climate and weather 6 2.3 Human use 6 2.4 Vegetation and flora 7 3 FAUNA 10 3.1 Breeding seabirds 10 3.2 Visiting seabirds 13 3.3 Shorebirds 13 3.4 Other indigenous fauna 14 4. INVASIVE SPECIES AND THEIR IMPACTS 15 4.1 Past invasives 15 4.2 House mouse 16 4.3 Feral house cat 17 5 ERADICATION BENEFITS, RISKS, COSTS AND FEASIBILITY 20 5.1 Benefits of cat eradication 20 5.2 Benefits of mouse eradication 20 5.3 Eradication Feasibility 21 5.4 Risks 24 5.5 Estimated Costs 25 6. Preliminary Recommendations 28 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 28 REFERENCES 28 APPENDICES – Flora species, Seabird status, Fly-ons, Pelagic counts 32 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study describes the biodiversity values of Malden Island, Kiribati, and assesses the potential benefits, feasibility and costs of removing key invasive species. Malden is relatively pest-free, but two significant invasive species are present - feral house cats and house mice. We believe that the most cost-effective and beneficial conservation action in the short term for Kiribati is to undertake a cat eradication programme. This would take pressure off nearly all of the 11 species of seabirds which currently breed at Malden, and allow for the natural and/or enhanced recovery of a further 5-6 species, including the Phoenix Petrel (EN). -

KIRIBATI Kiribati Isexpected to Incur, on Average, About 0.3 Million USD Per Year in Losses Due to Earthquakes And

PACIFIC CATASTROPHE RIS Public Disclosure Authorized S AKIRBAT Public Disclosure Authorized SEPTEMBER 2011 COUNTRY RISK PROFILE: KIRIBATI Kiribati isexpected to incur, on average, about 0.3 million USD per year in losses due to earthquakes and Public Disclosure Authorized tropical cyclones. In the next 50 years, Kiribati has a 50% chance of experiencing a loss exceeding 1 million USD and casualties larger than 10 people, and a 10% chance of experiencing a loss exceeding 40 million USD and casualties larger than 200 people. Public Disclosure Authorized BETTER RISK INFORMATION FOR SMARTER INVESTMENTS COUNTRY RISK PROFILE KIRIBAT POPULATION, BUILDINGS, INFRASTRUCTURE AND CROPS EXPOSED TO NATURAL PERILS 170'E 175*E 1801 175oW 170'W 165'W 160*W 155*W 150'W An extensive study has been conducted to assemble a - - dldFi comprehensive inventory of population and properties at risk. Properties include residential, commercial, public and industrial buildings; infrastructure assets such as major ports, Tarawa C airports, power plants, bridges, and roads; and major crops, such as coconut, palm oil, rice and many others. TABLE 1: ilometrs Summary of Exposure in Kiribati (2010) General Information: Taraw a Total Population: 101,400 024 8 GDPPer Capita (USD): 1,490 048 16 Total GDP (million USD): 151.2 Asset Counts: Residential Buildings: 24,879 Public Buildings: 1,103 Commercial, Industrial, and Other Buildings: 1,607 u idnta K All Buildings: 27,589 0 Cercial L Hectares of Major Crops: 18,633 0 Industrial Cost of Replacing Assets (million USD): 0 Public Buildings: 1,006 048 -16 Infrastructure: 164 Kilometers Crops: 11 TarawaSTh A Total: 1,181 Abaiang Government Revenue and Expenditure: Figure 1:Building locations. -

Research Article Ecosystem-Scale Effects of Nutrients and Fishing on Coral Reefs

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Marine Biology Volume 2011, Article ID 187248, 13 pages doi:10.1155/2011/187248 Research Article Ecosystem-Scale Effects of Nutrients and Fishing on Coral Reefs Sheila M. Walsh1, 2 1 Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA 2 Environmental Change Initiative, Brown University, Box 1951- 167 Thayer Street, 214 MacMillan Hall, Providence, RI 02912, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Sheila M. Walsh, sheila [email protected] Received 18 July 2010; Accepted 21 October 2010 Academic Editor: Kim Selkoe Copyright © 2011 Sheila M. Walsh. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Nutrient pollution and fishing are the primary local causes of coral reef decline but their ecosystem-scale effects are poorly understood. Results from small-scale manipulative experiments of herbivores and nutrients suggest prioritizing management of fishing over nutrient pollution because herbivores can control macroalgae and turf in the presence of nutrients. However, ecological theory suggests that the opposite occurs at large scales. Moreover, it is unclear whether fishing decreases herbivores because fishing of predators may result in an increase in herbivores. To investigate this paradox, data on the fish and benthic communities, fishing, and nutrients were collected on Kiritimati, Kiribati. Oceanographic conditions and a population resettlement program created a natural experiment to compare sites with different levels of fishing and nutrients. Contrary to theory, herbivores controlled macroalgae in the presence of nutrients at large spatial scales, and herbivores had greater effects on macroalgae when nutrients were higher. -

Women Producers in the Economy of Kiribati and Their Participation In

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Women producers of Kiribati and their participation in inter-island and international trade [email protected] http://unctad.org/gender UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Women producers of Kiribati and their participation in inter-island and international trade Geneva, 2020 © 2020, United Nations The work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of any firm or licensed process does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. References to country names in this publication correspond to the names in use historically during the periods for which data were reviewed. Photocopies and reproductions of excerpts are allowed with proper credits. This publication has been edited externally. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/DITC/2020/4 eISBN: 978-92-1-005559-8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by the Trade, Gender and Development Programme at UNCTAD. Inputs were provided by Tuiai Tabai. -

World Bank Document

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD3249 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 14.2 MILLION (US$19.5 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF KIRIBATI FOR A KIRIBATI: PACIFIC ISLANDS REGIONAL OCEANSCAPE PROGRAM February 20, 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Environment, Natural Resources & Blue Economy Global Practice East Asia And Pacific Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 31, 2019) Currency Unit = Australian Dollar (AU$) AU$1.43 = US$1 US$1.38283 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics AU$ Australian Dollar CBA Cost Benefit Analysis CBR Cost Benefit Ratio CPPL Central Pacific Producers Limited CEO Chief Executive Officer CFD Coastal Fisheries Division CFP Ciguatera Fish Poisoning CGAP Consolidated Gender Action Plan CMM Conservation and Management Measures CSU Central Services Unit DA Designated Account DLI Disbursement Linked Indicator DPWG Development Partner Working Group EM Electronic Monitoring ER Electronic Reporting EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework EU European Union FAD Fish Aggregating Device FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FFA Pacific