Platt-Nick.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Civilian Involvement in the 1990-91 Gulf War Through the Civil Reserve Air Fleet Charles Imbriani

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Civilian Involvement in the 1990-91 Gulf War Through the Civil Reserve Air Fleet Charles Imbriani Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE CIVILIAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE 1990-91 GULF WAR THROUGH THE CIVIL RESERVE AIR FLEET By CHARLES IMBRIANI A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2012 Charles Imbriani defended this dissertation on October 4, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Peter Garretson Professor Directing Dissertation Jonathan Grant University Representative Dennis Moore Committee Member Irene Zanini-Cordi Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to Fred (Freddie) Bissert 1935-2012. I first met Freddie over forty years ago when I stared working for Pan American World Airways in New York. It was twenty-two year later, still with Pan Am, when I took a position as ramp operations trainer; and Freddie was assigned to teach me the tools of the trade. In 1989 while in Berlin for training, Freddie and I witnessed the abandoning of the guard towers along the Berlin Wall by the East Germans. We didn’t realize it then, but we were witnessing the beginning of the end of the Cold War. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

2017 Fall Event Brochure

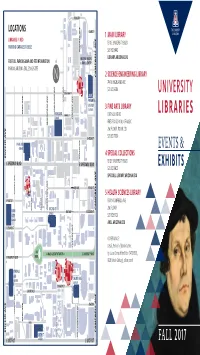

RING RD LOCATIONS ELM ST 1 MAIN LIBRARY LIBRARIES IN RED 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD PARKING GARAGES IN BLUE WARREN AVE WARREN 520.621.6442 ARIZONA HEALTH LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU FOR FULL PARKING MAP AND FEE INFORMATION SCIENCES CENTER PARKING.ARIZONA.EDU, 520.626.7275 CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL 2 SCIENCE-ENGINEERING LIBRARY 744 N HIGHLAND AVE 520.621.6384 E DRACHMAN ST UAMC VINE AVE PATIENT & VISITOR GARAGE 3 FINE ARTS LIBRARY HIGHLAND AVE PARK AVE PARK HIGHLAND E MABEL ST 1017 N OLIVE RD GARAGE AVE CHERRY FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN 2nd FLOOR, ROOM 233 E HELEN ST 520.621.7009 PARK AVE GARAGE 4 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS EUCLID AVE WARREN AVE WARREN 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD 520.621.6423 SPECCOLL.LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU ONE WAY E FIRST ST MUSIC TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL BLDG 5 HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY E FIRST ST 1501 N CAMPBELL AVE MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL PALM DR PALM OLIVE RD SECOND ST 2nd FLOOR MAIN ONE WAY E SECOND ST GATE GARAGE 520.626.6125 GARAGE AHSL.ARIZONA.EDU E SECOND ST COVER IMAGE: CHERRY AVE CHERRY Detail, Portrait of Martin Luther, OLD MALL CLOSED TO TRAFFIC E UNIVERSITY BLVD by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), MAIN E UNIVERSITY BLVD 1528 (Veste Coburg), oil on panel TYNDALL AVE GARAGE CHERRY AVE GARAGE E FOURTH ST E FOURTH ST CHERRY AVE CHERRY ENKE DR TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL PARK AVE PARK LOWELL CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL EUCLID AVE NAT’L CHAMPIONS DR CHAMPIONS NAT’L SIXTH ST HIGHLAND AVE E SIXTH ST GARAGE E SIXTH ST FALL 2017 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SPECIAL EVENTS speccoll.library.arizona.edu Library Cats Tech Breakfast Contact: Kathy McCarthy | 520.626.8332 Saturday, October 28, 9–11 a.m., Science-Engineering Library [email protected] All alumni and friends are welcome at our Homecoming EXHIBIT | Opens August 7 celebration. -

This List of Gestures Represents Broad Categories of Emotion: Openness

This list of gestures represents broad categories of emotion: openness, defensiveness, expectancy, suspicion, readiness, cooperation, frustration, confidence, nervousness, boredom, and acceptance. By visualizing the movement of these gestures, you can raise your awareness of the many emotions the body expresses without words. Openness Aggressiveness Smiling Hand on hips Open hands Sitting on edge of chair Unbuttoning coats Moving in closer Defensiveness Cooperation Arms crossed on chest Sitting on edge of chair Locked ankles & clenched fists Hand on the face gestures Chair back as a shield Unbuttoned coat Crossing legs Head titled Expectancy Frustration Hand rubbing Short breaths Crossed fingers “Tsk!” Tightly clenched hands Evaluation Wringing hands Hand to cheek gestures Fist like gestures Head tilted Pointing index finger Stroking chins Palm to back of neck Gestures with glasses Kicking at ground or an imaginary object Pacing Confidence Suspicion & Secretiveness Steepling Sideways glance Hands joined at back Feet or body pointing towards the door Feet on desk Rubbing nose Elevating oneself Rubbing the eye “Cluck” sound Leaning back with hands supporting head Nervousness Clearing throat Boredom “Whew” sound Drumming on table Whistling Head in hand Fidget in chair Blank stare Tugging at ear Hands over mouth while speaking Acceptance Tugging at pants while sitting Hand to chest Jingling money in pocket Touching Moving in closer Dangerous Body Language Abroad by Matthew Link Posted Jul 26th 2010 01:00 PMUpdated Aug 10th 2010 01:17 PM at http://news.travel.aol.com/2010/07/26/dangerous-body-language-abroad/?ncid=AOLCOMMtravsharartl0001&sms_ss=digg You are in a foreign country, and don't speak the language. -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Legacy of a Mad Scientist

i JOHN CARRICK “First, I'd like to know, do any of you have experience in the martial arts?" About half the hands went up. Ashley didn't raise her hand, despite two previous summers of similar courses; she did not count herself as experienced. "Now, how many of you have been hit, hard, in the face?" Sihing Shou asked. At first several hands went up, but some were timid, uncertain. "I mean really hit hard; bloody nose, fat lip, black eye. How many?" Only a few hands remained aloft. Shou pointed to one boy and asked, "Who hit you?" "My brother hits me all the time," he said, pointing at his brother, standing a few spaces away. Shou and several others laughed. Ashley noticed that the boy, however, was not laughing. She suspected he was very interested in how to put a stop his brother’s dominance. "And you?" Shou gestured to another boy. "My father," came the answer. Shou pointed again. "A kid in my class." "Has anyone here ever been hit while in the ring?" Shou asked. All the hands went down. "When you are in a fight, if you are ever in a fight, you must fight for your life. It will be at that moment when you are weak, tired, probably very hurt, that is when you must act to save your life. We will help you get to that place and teach you how to think while you're there." Instructor Shou walked along the front of the room. "Someone may come; an outlaw, the government, a king, they may take all of your possessions. -

Gwendolyn Whiteside …………………………………………………………...…..Page 4

BACKSTAGE A publication of COMMUNITY SERVICE at AMERICAN BLUES THEATER THE COLUMNIST BACKSTAGE GUIDE 1 BACKSTAGE THE COLUMNIST By David Auburn Directed by Keira Fromm FEATURING Philip Earl Johnson Kymberly Mellen Coburn Goss Ian Paul Custer* Tyler Meredith Christopher Sheard From the Pulitzer and Tony Award-winning author of Proof, The Columnist is a drama about power, the press, sex, and betrayal. At the height of the Cold War, Joe Alsop is the nation’s most influential journalist—beloved, feared, and courted by the Washington world. But as the 1960s dawn and America undergoes dizzying change, the intense political dramas Joe is embroiled in become deeply personal as well. “Gripping and moving” – Variety * Ensemble member of American Blues Theater 2 AMERICAN BLUES THEATER TABLE OF CONTENTS Note from Producing Artistic Director Gwendolyn Whiteside …………………………………………………………...…..Page 4 About Playwright David Auburn..................................................................................................................Page 5 Interview with Playwright David Auburn........................………………….……………………………………………..........Page 6 The Backstory with Actor Ian Paul Custer....……....…………………………....…………………....................................Page 7 About David Halberstam.................................................…………………………………………….………………...……....Page 7 Interview with Actors Philip Earl Johnson and Kymberly Mellen…………………………………………................Pages 8-9 Interview with Costume Designer Christopher J. Neville......…...….....................................................Pages -

RICHARD M. BISSELL JR. PAPERS SUBJECT SERIES 1935 – 1994; Boxes 1 - 12

RICHARD M. BISSELL JR. PAPERS SUBJECT SERIES 1935 – 1994; Boxes 1 - 12 SERIES DESCRIPTION Alphabetical Subseries: Boxes 1 - 5 Alphabetical/Intelligence Subseries: Boxes 6 - 12 CONTENT This series contains an alphabetical listing of subjects pertaining to Richard M. Bissell Jr.’s personal and professional lives. Included herein are files documenting his childhood, his personal life, his career at the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA), his career at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), organizations to which he belonged, individuals with whom he had personal and professional relationships, and other topics. Document types include correspondence, interviews, memoranda, newspaper clippings, reports, magazine articles and notes. This series contains the bulk of the information in this collection regarding the Central Intelligence Agency to be found in this collection. Further information relating to the Central Intelligence Agency may be found in the Correspondence Series, the Historic and Oversize Papers Series, the Interviews Series, the Oral History Interviews Series. Document copies marked “Original filed for safekeeping” were created by Bissell’s office staff who then filed the originals in what is now the Historic Papers, Oversize Objects and Clippings Series of this collection. As was his apparent practice, many of Bissell’s notes in this series are written on the reverse of University of Hartford budget documents as well as on unused letterhead. STRUCTURE This series arrived at the library divided into two alphabetized subseries; a collection of alphabetized subject files relating to various facets of Richard M. Bissell’s personal and professional lives from childhood to retirement, and a collection of alphabetized files related to matters of intelligence and intelligence gathering. -

Vice President's Meeting with People's Republic of China Vice Premier

W':' S C1 i NG'ON <!fOP ::!f!C~ / SENSITIVE / EYES ONLY MEMO~~DUM OF CONVERSA~ION SUBJECT: S~~ary of the Vice President ' s Meeting with People's Republic of China Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping PARTICIPP.. NTS : Vice President Walter Mondale Leonard Woodcock, U.S. Ambassador to the People's Republic of China David Aaron, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affa~rs Richard Moe, Chief of Staff to the Vice President Denis Clift, Assistant to the Vice President for National Security Affairs Richard Holbrooke, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affair Michel Oksenberg, St"_aff Member I NSC Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping Huang Hua, Minister of Foreign Affairs Chai Zemin, People's Republic of China Ambassador to the United States Zhang Wenjin, Deputy Foreign Minister Han Xu, Director of American Depar~~ent Wei Yongqing, Director of Protocol Ji Chaozhu, Deputy Director of American Depart.:nent DATE, TD1E August 28, 1979; 9:30 a.m. - 12:00 Noon k'lD PLACE: The Great Hall of the People, Beijing, People's Republic of China Vi=e Premier Deng: I heard your speech ;vas war:nly ;.;elcomed. Vice ?res:":ient ~oncale: I W2.S thril2.ed by t.he opportunity to spea2< at your great unive.r·sity anc. -='0 speak to the people. It was an unprecedented occasion, and I t.hank you for that. cpport"..lni ty. DECLASSIFIED \E.O.12958, Sec.3.6 :~_R--I.~~__ NA~ ::T~31m;:J" ,TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE/ EYES ONLY 2 Vice Premier Deng: It was published in full in today ' s People's Daily.