Bisphosphonates: Addressing the Duration Conundrum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fosavance, INN-Alendronic Acid and Colecalciferol

EMA/175858/2015 EMEA/H/C/000619 EPAR summary for the public Fosavance alendronic acid and colecalciferol This is a summary of the European public assessment report (EPAR) for Fosavance. It explains how the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) assessed the medicine to reach its opinion in favour of granting a marketing authorisation and its recommendations on the conditions of use for Fosavance. What is Fosavance? Fosavance is a medicine that contains two active substances: alendronic acid and colecalciferol (vitamin D3). It is available as tablets (70 mg alendronic acid and 2,800 international units [IU] colecalciferol; 70 mg alendronic acid and 5,600 IU colecalciferol). What is Fosavance used for? Fosavance (containing either 2,800 or 5,600 IU colecalciferol) is used to treat osteoporosis (a disease that makes bones fragile) in women who have been through the menopause and are at risk of low vitamin D levels. Fosavance 70 mg/5,600 IU is for use in patients who are not taking vitamin D supplements. Fosavance reduces the risk of fractures (broken bones) in the spine and the hip. The medicine can only be obtained with a prescription. How is Fosavance used? The recommended dose of Fosavance is one tablet once a week. It is intended for long-term use. The patient must take the tablet with a full glass of water (but not mineral water), at least 30 minutes before any food, drink or other medicines (including antacids, calcium supplements and vitamins). To avoid irritation of the oesophagus (the tube that leads from the mouth to the stomach), the patient should not lie down until after their first food of the day, which should be at least 30 minutes after taking the tablet. -

Adrovance, INN-Alendronic Acid

EMA/194587/2011 EMEA/H/C/000759 EPAR summary for the public Adrovance alendronic acid / colecalciferol This is a summary of the European public assessment report (EPAR) for Adrovance. It explains how the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) assessed the medicine to reach its opinion in favour of granting a marketing authorisation and its recommendations on the conditions of use for Adrovance. What is Adrovance? Adrovance is a medicine that contains two active substances: alendronic acid and colecalciferol (vitamin D3). It is available as white tablets (capsule-shaped: 70 mg alendronic acid and 2,800 international units [IU] colecalciferol; rectangular: 70 mg alendronic acid and 5,600 IU colecalciferol). What is Adrovance used for? Adrovance (containing either 2,800 or 5,600 IU colecalciferol) is used to treat osteoporosis (a disease that makes bones fragile) in women who have been through the menopause and are at risk of low vitamin D levels. Adrovance 70 mg/5,600 IU is for use in patients who are not taking vitamin D supplements. Adrovance reduces the risk of broken bones in the spine and the hip. The medicine can only be obtained with a prescription. How is Adrovance used? The recommended dose of Adrovance is one tablet once a week. It is intended for long-term use. The patient must take the tablet with a full glass of water (but not mineral water), at least 30 minutes before any food, drink or other medicines (including antacids, calcium supplements and vitamins). To avoid irritation of the oesophagus (gullet), the patient should not lie down until after their first food of the day, which should be at least 30 minutes after taking the tablet. -

Bisphosphonates Can Be Safely Given to Patients with Hypercalcemia And

Clinical Research in Practice: The Journal of Team Hippocrates Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 11 2019 Bisphosphonates can be safely given to patients with hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency secondary to multiple myeloma Matthew .J Miller Wayne State University School of Medicine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/crp Part of the Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism Commons, Medical Education Commons, Nephrology Commons, and the Translational Medical Research Commons Recommended Citation MILLER MJ. Bisphosphonates can be safely given to patients with hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency secondary to multiple myeloma. Clin. Res. Prac. 2019 Mar 14;5(1):eP1846. doi: 10.22237/crp/1552521660 This Critical Analysis is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Clinical Research in Practice: The ourJ nal of Team Hippocrates by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. VOL 5 ISS 1 / eP1846 / MARCH 14, 2019 doi: 10.22237/crp/1552521660 Bisphosphonates can be safely given to patients with hypercalcemia and renal insufficiency secondary to multiple myeloma MATTHEW J. MILLER, B.S., Wayne State University School of Medicine, [email protected] ABSTRACT A critical appraisal and clinical application of Itou K, Fukuyama T, Sasabuchi Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of oral rehydration therapy until 2 h before surgery: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anesthesia. 2012;26(1):20-27. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1261-x. Keywords: bisphosphonates, nephrotoxicity, safety, renal insufficiency, renal failure, multiple myeloma, pamidronate, ibandronate, zaledronic acid Clinical Context An 83-year-old African-American female with a history of multiple vertebral compression fractures and gastritis presented for the second time in two weeks with symptoms of hypercalcemia. -

Re-Evaluated Data of Dissociation Constants of Alendronic, Pamidronic and Olpadronic Acids

Cent. Eur. J. Chem. • 7(1) • 2009 • 8-13 DOI: 10.2478/s11532-008-0099-z Central European Journal of Chemistry Re-evaluated data of dissociation constants of alendronic, pamidronic and olpadronic acids Invited Paper Alexander P. Boichenko1, Vadim V. Markov1, Hoan Le Kong1, Anna G. Matveeva2, Lidia P. Loginova1* 1Department of Chemical Metrology, Kharkov V.N. Karazin National University, 61077 Kharkov, Ukraine. 2A.N. Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119991 Moscow, Russian Federation Received 01 April 2008; Accepted 23 October 2008 Abstract: The dissociation constants of (4-amino-1-hydroxybutylidene)bisphosphonic (alendronic) acid, (3-(dimethylamino)-1- hydroxypropylidene)bisphosphonic (olpadronic) acid and (3-amino-1-hydroxypropylidene)bisphosphonic (pamidronic) acid were obtained in aqueous solutions (0.10 М КСl) and micellar solutions of cetylpyridinium chloride (0.10 М CPC) at 25.0°C. With the exception of the third dissociation constant of alendronic acid, the dissociation constants of alendronic, olpadronic and pamidronic acids in aqueous solutions matched literature data. The possibility of sodium alendronate determination by acid-base titration by NaOH solution was theoretically grounded on the basis of re-evaluated data of alendronic acid dissociation constants. Keywords: Alendronate • Olpadronate, pamidronate, dissociation constant • Micellar media effect © Versita Warsaw and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 1. Introduction spectrometric [12], refractive index [13] and Sodium salts of (4-amino-1-hydroxybutylidene) conductometric [14] detection have been proposed. bisphosphonic (alendronic) acid, (3-(dimethylamino)- The anion-exchange chromatography with refractive 1-hydroxypropylidene)bisphosphonic (olpadronic) acid index detection is recommended by British and (3-amino-1-hydroxypropylidene)bisphosphonic Pharmacopoeia for the determination of sodium (pamidronic) acid are successfully used for the medical alendronate [15]. -

6. Endocrine System 6.1 - Drugs Used in Diabetes Also See SIGN 116: Management of Diabetes, 2010

1 6. Endocrine System 6.1 - Drugs used in Diabetes Also see SIGN 116: Management of Diabetes, 2010 http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/116 Insulin Prescribing Guidance in Type 2 Diabetes http://www.fifeadtc.scot.nhs.uk/media/6978/insulin-prescribing-in-type-2-diabetes.pdf 6.1.1 Insulins (Type 2 Diabetes) 6.1.1.1 Short Acting Insulins 1st Choice – Insuman® Rapid (Human Insulin) – Humulin S® – Actrapid® 2nd Choice – Insulin Aspart (NovoRapid®) (Insulin Analogues) – Insulin Lispro (Humalog®) 6.1.1.2 Intermediate and Long Acting Insulins 1st Choice – Isophane Insulin (Insuman Basal®) (Human Insulin) – Isophane Insulin (Humulin I®) – Isophane Insulin (Insulatard®) 2nd Choice – Insulin Detemir (Levemir®) (Insulin Analogues) – Insulin Glargine (Lantus®) Biphasic Insulins 1st Choice – Biphasic Isophane (Human Insulin) (Insuman Comb® ‘15’, ‘25’,’50’) – Biphasic Isophane (Humulin M3®) 2nd Choice – Biphasic Aspart (Novomix® 30) (Insulin Analogues) – Biphasic Lispro (Humalog® Mix ‘25’ or ‘50’) Prescribing Points For patients with Type 1 diabetes, insulin will be initiated by a diabetes specialist with continuation of prescribing in primary care. Insulin analogues are the preferred insulins for use in Type 1 diabetes. Cartridge formulations of insulin are preferred to alternative formulations Type 2 patients who are newly prescribed insulin should usually be started on NPH isophane insulin, (e.g. Insuman Basal®, Humulin I®, Insulatard®). Long-acting recombinant human insulin analogues (e.g. Levemir®, Lantus®) offer no significant clinical advantage for most type 2 patients and are much more expensive. In terms of human insulin. The Insuman® range is currently the most cost-effective and preferred in new patients. KEY:- H – Hospital Use Only S – Specialist Initiation or Recommendation R – Restricted Use Only Fife Formulary February 2014 Last Amended June 2015 2 Patients already established on insulin should not be switched to alternative products unless recommended by a diabetes specialist. -

Phvwp Class Review Bisphosphonates and Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (Alendronic Acid, Clodronic Acid, Etidronic Acid, Ibandronic

PhVWP Class Review Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw (alendronic acid, clodronic acid, etidronic acid, ibandronic acid, neridronic acid, pamidronic acid, risedronic acid, tiludronic acid, zoledronic acid), SPC wording agreed by the PhVWP in February 2006 Section 4.4 Pamidronic acid and zoledronic acid: “Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported in patients with cancer receiving treatment regimens including bisphosphonates. Many of these patients were also receiving chemotherapy and corticosteroids. The majority of reported cases have been associated with dental procedures such as tooth extraction. Many had signs of local infection including osteomyelitis. A dental examination with appropriate preventive dentistry should be considered prior to treatment with bisphosphonates in patients with concomitant risk factors (e.g. cancer, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, corticosteroids, poor oral hygiene). While on treatment, these patients should avoid invasive dental procedures if possible. For patients who develop osteonecrosis of the jaw while on bisphosphonate therapy, dental surgery may exacerbate the condition. For patients requiring dental procedures, there are no data available to suggest whether discontinuation of bisphosphonate treatment reduces the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clinical judgement of the treating physician should guide the management plan of each patient based on individual benefit/risk assessment.” Remaining bisphosphonates: “Osteonecrosis of the jaw, generally associated with tooth extraction and/or local infection (including osteomyelits) has been reported in patients with cancer receiving treatment regimens including primarily intravenously administered bisphophonates. Many of these patients were also receiving chemotherapy and corticosteroids. Osteonecrosis of the jaw has also been reported in patients with osteoporosis receiving oral bisphophonates. A dental examination with appropriate preventive dentistry should be considered prior to treatment with bisphosphonates in patients with concomitant risk factors (e.g. -

834FM.1 ZOLEDRONIC ACID and IBANDRONIC ACID for ADJUVANT TREATMENT in EARLY BREAST CANCER PATIENTS (Amber Initiation Guideline for Ibandronic Acid)

834FM.1 ZOLEDRONIC ACID AND IBANDRONIC ACID FOR ADJUVANT TREATMENT IN EARLY BREAST CANCER PATIENTS (Amber Initiation Guideline for Ibandronic Acid) This guideline provides prescribing and monitoring advice for oral ibandronic acid therapy which may or may not follow zoledronic acid infusions in secondary care. It should be read in conjunction with the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) available on www.medicines.org.uk/emc and the BNF. BACKGROUND FOR USE Bisphosphonates are indicated for reduction in the risk of developing bone metastases and risk of death from breast cancer in post-menopausal patients who have had curative treatment for breast cancer, i.e. this is an adjuvant treatment. A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 26 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including 18,766 women with early breast cancer (the Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group [EBCTCG] meta- analysis 2015) has shown that at 10 years the absolute reductions in the risk of breast cancer mortality, bone recurrence and all-cause mortality in post-menopausal women were 3.3%, 2.2% and 2.3% respectively. Bone fractures were also reduced by 15%, which is highly relevant as many of the patients offered adjuvant bisphosphonates will also be recommended to have adjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment that can cause loss of bone density and bone fractures. In line with cancer services in Oxfordshire and other areas, we have chosen to use zoledronic acid for intravenous administration and ibandronic acid for oral administration due to availability and relatively low cost. These medications are licensed for use in patients with osteoporosis and metastatic breast cancer. -

Poster EAHP 140320

Nº: 5PSQ-069 ATC code: M05 Roura J1, Rovira M1,2, Socoro N1, Ruiz S1, Sotoca JM1,2 1 Pharmacy Service, Division of Medicines, Hospital Clínic Barcelona, Barelona, Spain 2 Consorci d’Atenció Primària de Salut de Barcelona Esquerra, Barcelona, Spain [email protected] BACKGROUND AND IMPORTANCE • Falls among the older population are associated with a high morbidity and mortality. • The etiology of falls is usually multifactorial and the use of several types of drugs has been associated with an increased fall risk. • Since drugs are a modifiable risk factor, periodic drug review and eventual withdrawal of drug-related falls could be a possible strategy to prevent falls in this population. AIM AND OBJECTIVES The aim was to analyze the proportion of patients who were treated for osteoporosis and were taking, concomitantly, any drug that increase fall risk. MATERIAL AND METHODS q Observational, retrospective study in three primary care centres covering a population of 97,722 people. q Study population: patients with a prescription of any drug for osteoporosis. q Data collected were: age, gender, drugs for osteoporosis treatment and drugs that have a medium or high fall risk. RESULTS q 1,594 patients were treated with drugs for q Patients according to the number of drugs with osteoporosis falling risk concomitantly prescribed: 38.5% had Demographic data (n=1,594) one; 30.5% two; 17.9% three; 8.7% four and 4.4% five or more. Age – years* 72.4 ± 10.6 q Drugs for osteoporosis treatment are represented Female sex – n (%) 1,457 (91.5) in Figure 1. -

Zoledronic Acid Teva, INN-Zoledronic Acid

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Zoledronic Acid Teva 4 mg/5 ml concentrate for solution for infusion 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION One vial with 5 ml concentrate contains 4 mg zoledronic acid (as monohydrate). One ml concentrate contains 0.8 mg zoledronic acid (as monohydrate). For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Concentrate for solution for infusion (sterile concentrate). Clear and colourless solution. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications - Prevention of skeletal related events (pathological fractures, spinal compression, radiation or surgery to bone, or tumour-induced hypercalcaemia) in adult patients with advanced malignancies involving bone. - Treatment of adult patients with tumour-induced hypercalcaemia (TIH). 4.2 Posology and method of administration Zoledronic Acid Teva must only be prescribed and administered to patients by healthcare professionals experienced in the administration of intravenous bisphosphonates. Posology Prevention of skeletal related events in patients with advanced malignancies involving bone Adults and older people The recommended dose in the prevention of skeletal related events in patients with advanced malignancies involving bone is 4 mg zoledronic acid every 3 to 4 weeks. Patients should also be administered an oral calcium supplement of 500 mg and 400 IU vitamin D daily. The decision to treat patients with bone metastases for the prevention of skeletal related events should consider that the onset of treatment effect is 2-3 months. Treatment of TIH Adults and older people The recommended dose in hypercalcaemia (albumin-corrected serum calcium ≥ 12.0 mg/dl or 3.0 mmol/l) is a single dose of 4 mg zoledronic acid. -

Zoledronic Acid Injection Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Zoledronic Acid Injection safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Zoledronic Acid Injection. • Adequately rehydrate patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy Zoledronic Acid Injection prior to administration of Zoledronic Acid Injection and monitor electrolytes during treatment. (5.2) for intravenous use • Renal toxicity may be greater in patients with renal impairment. Do Initial U.S. Approval: 2001 not use doses greater than 4 mg. Treatment in patients with severe renal impairment is not recommended. Monitor serum creatinine -------------------------RECENT MAJOR CHANGES--------------------- before each dose. (5.3) • Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported. Preventive dental exams Warnings and Precautions, Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (5.4) 06/2015 should be performed before starting Zoledronic Acid Injection. Avoid invasive dental procedures. (5.4) -------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE------------------------ • Severe incapacitating bone, joint, and/or muscle pain may occur. Zoledronic Acid Injection is a bisphosphonate indicated for the Discontinue Zoledronic Acid Injection if severe symptoms occur. treatment of: (5.5) • Hypercalcemia of malignancy. (1.1) • Zoledronic Acid Injection can cause fetal harm. Women of • Patients with multiple myeloma and patients with documented bone childbearing potential should be advised of the potential hazard to metastases from solid tumors, in conjunction with standard the fetus and to avoid becoming pregnant. (5.9, 8.1) antineoplastic therapy. Prostate cancer should have progressed after • Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures have been treatment with at least one hormonal therapy. (1.2) reported in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. These Important limitation of use: The safety and efficacy of Zoledronic Acid fractures may occur after minimal or no trauma. -

The Role of Bone Modifying

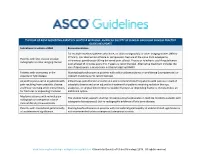

THE ROLE OF BONE MODIFYING AGENTS IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA: AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE UPDATE Indications to initiate a BMA Recommendation For multiple myeloma patients who have, on plain radiograph(s) or other imaging studies (MRI or CT Scan), lytic destruction of bone or compression fracture of the spine from osteopenia, Patients with lytic disease on plain intravenous pamidronate 90 mg delivered over at least 2 hours or zoledronic acid 4 mg delivered radiographs or other imaging studies over at least 15 minutes every 3 to 4 weeks is recommended. Alternative treatment includes the use of denosumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL. Patients with osteopenia in the Starting bisphosphonates in patients with solitary plasmacytoma or smoldering (asymptomatic) or absence of lytic disease indolent myeloma is not recommended. Adjunct to pain control in patients with Intravenous pamidronate or zoledronic acid is recommended for patients with pain as a result of pain resulting from osteolytic disease osteolytic disease and as an adjunctive treatment for patients receiving radiation therapy, and those receiving other interventions analgesics, or surgical intervention to stabilize fractures or impending fractures. Denosumab is an for fractures or impending fractures additional option. Myeloma patients with normal plain The Update Panel supports starting intravenous bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma patients with radiograph or osteopenia in bone osteopenia (osteoporosis) but no radiographic evidence of lytic bone disease. mineral density measurements Patients with monoclonal gammopathy Starting bisphosphonates in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is of undetermined significance not recommended unless osteopenia (osteoporosis) exists. www.asco.org/hematologic-malignancies-guidelines ©American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr Zoledronic Acid

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr Zoledronic Acid - A (zoledronic acid injection) 5 mg/100 mL solution for intravenous infusion Bone Metabolism Regulator Sandoz Canada Inc. Date of Revision: 145 Jules-Léger June 01, 2016 Boucherville, QC, Canada J4B 7K8 Control No. : TBD Zoledronic Acid – A Page 1 of 62 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION ............................................................ 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ........................................................................... 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ................................................................................. 3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ....................................................................................................... 4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ..................................................................................... 4 ADVERSE REACTIONS ..................................................................................................... 10 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ................................................................................. 25 OVERDOSAGE ..................................................................................................................... 27 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY............................................................... 27 STORAGE AND STABILITY ............................................................................................. 30 SPECIAL HANDLING INSTRUCTIONS .......................................................................... 30