Perrotte V New York City Transit Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

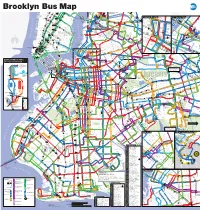

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

58-12 QUEENS BOUELVARD Staples Shopping Center WOODSIDE QUEENS | NEW YORK

RETAIL SPACE 58-12 QUEENS BOUELVARD Staples Shopping Center WOODSIDE QUEENS | NEW YORK SIZE 2,775 SF TAXES, CAM, INSURANCE $13.66 CO-TENANTS Staples NEIGHBORS Rite Aid, CVS, Key Food, Big Six Fitness, KFC, Dollar Tree, Dunkin’, Domino’s, Subway 59th Street COMMENTS 120 Apartments and 20,000 SF of Occupied Office Space Above Adjacent to Big Six Towers, with 700+ Residential CONTACT EXCLUSIVE AGENTS Apartments DANIEL GLAZER DOUG WEINSTEIN Buses: Q60 - 4,752,023 riders annually [email protected] [email protected] Subway: 77 516.933.8880 516.933.8880 46 St, Bliss Station 4,058,815 riders annually 100 Jericho Quadrangle Suite 120 Please visit us at ripcony.com for more information Jericho, NY 11753 This information has been secured from sources we believe to be reliable, but we make no representations as to the accuracy of the 516.933.8880 information. References to square footage are approximate. Buyer must verify the information and bears all risk for any inaccuracies. QUEENS, NEW YORK MARKET AERIAL TRIANGLE CENTER COLLEGE POINT CENTER CLEARVIEW EXPRESSWAY GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY 161,909 VPD 157,222 VPD PLAZA 48 SHOPS AT NORTHERN BOULEVARD 48,806 VPD 97,376 VPD COMING SOON 34,980 VPD NORTHERN BOULEVARD SKY VIEW CENTER 31,630 VPD FACTORY OUTLET carter’s NYC TRANSIT AUTHORITY carter’s QUEENS PLACE QUEENS CENTER 52,070 VPD NYC TRANSIT AUTHORITY NYC TRANSIT AUTHORITY VAN WYCK EXPRESSWAY FACTORY OUTLET QUEENS BOULEVARD 164,677 VPD 37,750 VPD 188,246 VPD 2,775 SF END CAP 150,062 VPD 58-12 Queens Blvd THE SHOPS AT GRAND AVENUE WOODSIDE, LONGQUEENS -

COVID-19 Questions and Answers – Current As of August 23, 2021

PHFA Multifamily Division COVID-19 Questions and Answers – Current as of August 23, 2021 PHFA continues to monitor the situation surrounding COVID-19 and its impact on our multifamily partners. This Q&A is not exhaustive but addresses frequent questions we have received to date. We encourage you to utilize the resources listed below and consult your attorney when appropriate. Properties should continue to follow the most recent federal and state mandates and guidance provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PHFA will update this document and post new versions on our website as additional information is provided. The following Q&A is organized by each housing management department. Multiple departments may apply to a single property. We encourage you to read through the entire Q&A. Each department has listed the best way to contact their staff during this time. PHFA employees are actively monitoring their email throughout the day. Whenever possible, we encourage using email to contact PHFA. While phones are being monitored, email will allow for a faster response. Project Operations – Agency Funded Properties (HOME, PHARE, Keystone, National Housing Trust Fund, Agency Mortgages) Q1. What is the best way to contact your Housing Management Representative during the COVID- 19 office closure? A1. While PHFA’s physical offices are closed, PHFA staff is working remotely from home. Please use email to communicate with the Housing Management Representative (HMR) assigned to your property. If you do not have this information, contact Barb Huntsinger at [email protected]. There may be some instances when response time is slower than usual due to the nature of working remotely. -

Our Brochure

POLICY ON ADVANCE DIRECTIVES DIRECTIONS QBEC is an Ambulatory Surgical Center. Since the patient stay is QBEC is located on the third floor of 95-25 Queens Boulevard. The entrance to expected to be brief (no overnight), the Center does not accept “Advance 95-25 Queens Boulevard is located on the North East of Queens Boulevard Directives” such as “Living Will,” Healthcare Proxy, or “Do Not Resuscitate and 62nd Dr. (DNR)” orders. If the patient chooses to maintain the “Advance Directive” status, the patient may seek treatment at a facility such as a hospital that would accept the "Advance Directives". If you have executed "Advance Directives", QBEC would like to maintain a copy on file to be passed on to the hospital personnel in case you (the patient) required to be transferred to the hospital for emergency medical care. NEW YORK STATE LAW New York State Law allows the patients to provide physicians “Advance Directives” under “Patients’ Rights in State of New York.” For more Queens Blvd (25) nd Dr information and relevant forms please visit: J 62 u n http://www.health.state.ny.us/professionals/patients/patient_rights/ c t i o W n B LIVING WILL oodhaven Blvd l v d Living Will is a document that contains your health care wishes and is addressed to unnamed family, friends, hospitals, and other health care e v d A rd d rd R D n 63 facilities. You may use a Living Will to specify your wishes about life- Eliot Ave 3 2 6 prolonging procedures and other end-of-life care so that your specific 6 instructions can be read by your caregivers when you are unable to t S S a communicate your wishes. -

Q72 Local Service

Bus Timetable Effective Spring 2018 MTA Bus Company Q72 Local Service a Between Rego Park and LaGuardia Airport If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride Express Bus Plus MetroCard allows free transfers between express buses, local buses and subways, including SIR, while Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but express buses. Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value (between subway and local bus and local bus to local bus, etc.) if you complete your transfer within two hours of paying your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you transfer from a local bus or subway to an express bus you must pay an additional $3.75 from that same MetroCard. You may transfer free from an express bus, to a local bus, to the subway, or to another express bus if you use the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare in coins, you can request a transfer good only on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. -

Q60 Queens Blvd

Bus Timetable Q60 MTA Bus Company Queens Blvd. - East Midtown Via Queens Blvd / Sutphin Blvd Local Service For accessible subway stations, travel directions and other information: Effective September 5, 2021 Visit www.mta.info or call us at 511 We are introducing a new style to our timetables. These read better on mobile devices and print better on home printers. This is a work in progress — the design will evolve over the coming months. Soon, we'll also have an online timetable viewer with more ways to view timetables. Let us know your thoughts, questions, or suggestions about the new timetables at new.mta.info/timetables-feedback. Q60 Weekday To South Jamaica, Queens E Midtown Sunnyside Woodside Elmhurst Forest Hills Kew Gardens Jamaica S Jamaica E 60 St / 2 Av Queens Bl / 35 Queens Bl / 60 Queens Bl / Queens Bl / 71 Queens Bl / 80 Sutphin Bl / 91 157 St / 109 Av St St Woodhaven Bl Av Rd Av 2:00 2:07 2:16 2:26 2:35 2:41 2:49 2:54 2:30 2:37 2:46 2:56 3:05 3:11 3:19 3:24 3:00 3:07 3:16 3:26 3:35 3:41 3:49 3:54 3:30 3:37 3:46 3:56 4:05 4:11 4:19 4:24 4:00 4:07 4:16 4:26 4:35 4:41 4:49 4:54 4:30 4:37 4:46 4:56 5:05 5:11 5:19 5:23 5:00 5:08 5:17 5:27 5:37 5:43 5:51 5:55 5:30 5:38 5:47 5:57 6:07 6:13 6:22 6:27 5:50 5:58 6:07 6:19 6:31 6:37 6:46 6:51 6:09 6:20 6:31 6:43 6:55 7:01 7:11 - 6:30 6:41 6:52 7:04 7:19 7:27 7:37 7:44 6:45 6:56 7:07 7:22 7:37 7:45 7:55 - 7:00 7:12 7:25 7:40 7:55 8:03 8:13 8:20 7:15 7:27 7:40 7:55 8:10 8:18 8:28 8:35 7:30 7:42 7:55 8:10 8:25 8:33 8:43 8:50 7:45 7:57 8:10 8:25 8:40 8:48 8:58 - 7:58 8:10 8:23 8:38 8:53 -

Q43 SCHEDULE CONTINUES INSIDE — Page 5 — Q43 Limited Weekday Service from Jamaica to Floral Park

Bus Timetable Effective as of January 6, 2019 New York City Transit Q43 Local and Limited-Stop Service a Between Floral Park and Jamaica If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full fare. -

Fall 2019 for ADULTS (17 YEARS and OLDER) Beginning and Intermediate Levels

FREE ENGLISH CLASSES Fall 2019 FOR ADULTS (17 YEARS AND OLDER) Beginning and Intermediate Levels REGISTER IN PERSON at the community libraries listed. ATTENTION Returning Students from Spring 2019: Please bring your ESOL Registration Card with post-test score to register. SPACE IS LIMITED ON A FIRST-COME FIRST-SERVED BASIS An English test will be given for class placement. Only up to 30 students will be registered for each class. Others will be put on a waiting list, or referred to our Adult Learning Centers or other programs. QueensLibrary.org Queens Public Library is an independent, not-for-profit corporation and is not affiliated with any other library system. 20599-06/19 ESOL PROGRAMESOL PROGRAM WEEKDAY – MORNING CLASSES, FALL 2019 LIBRARY/LOCATION CLASS DAYS/HOURS LEVEL REGISTRATION DATE Corona Wednesday & Friday Intermediate Wednesday, September 18, 10:00 AM 38-23 104th Street 10:00am to 1:00pm East Flushing Tuesday & Thursday Intermediate Tuesday, September 17, 10:00 AM 196-36 Northern Blvd. 10:00am to 1:00pm Forest Hills Monday & Wednesday Intermediate Wednesday, September 11, 10:00 AM 108-19 71st Avenue 10:30am to 1:30pm Hollis Wednesday & Friday Beginning Wednesday, September 18, 10:00 AM 202-05 Hillside Avenue. 10:00am to 1:00pm Langston Hughes Monday & Wednesday 100-01 Northern Blvd., Corona 10:30am to 1:30pm Intermediate Monday, September 9, 10:00 AM Lefrak City Wednesday & Friday Beginning Friday, September 20, 10:00 AM 98-30 57th Ave., Corona 10:00am to 1:00pm McGoldrick Tuesday & Thursday Beginning Tuesday, September 17, -

April 2017 NYC Community Board #4 Queens

NYC Community Board #4 Queens 46-11 104th Street - Corona, NY 11368 Damian Vargas, Chairperson Phone: (718)-760-3141 / Fax:(718)-760-5971 Christian Cassagnol, District Manager Email: [email protected] Website : nyc.gov/queenscb4 April 2017 COMMUNITY BOARD MEETING NOTICE Tuesday April 11, 2017 7:30 pm VFW Post #150 51-11 108th Street Corona, NY 11368 AGENDA 1. Pledge of Allegiance 8. Report and Vote: Public Safety Committee 2. Roll Call SLA Applications 3. Vote: Minutes of March 21st Meeting (See Insert) 4. Report of the Chairperson 9. Committee Reports 5. Report of the District Manager Consumer Affairs Transportation 6. Report of the Legislators Environmental ULURP/Zoning Health Youth Parks 7. Speaker: Lillian Reyes, Senior Outreach Coordinator Green Thumb 10. Public Forum Community Gardens within Community Board 4 Good and Welfare of the District 11. Adjournment The next CB4Q Meeting will take place on May 9th. Please contact the CB Office before ANY meeting to be sure that it has not been cancelled or rescheduled! Important Dates to Remember Tuesday April 4th Public Safety Committee Meeting - 7:00pm (CB4Q Office - 46-11 104th Street) Tuesday April 4th ULURP/Zoning Committee Meeting - 7:00pm (Queens Center Mall Community Room - 90-15 Queens Blvd) Wednesday April 5th National Crime Victim’s Rights Week event hosted by Queens DA Brown and BP Katz - 10:30am (Queens Borough Hall - 120-55 Queens Blvd.) Thursday April 6th CM Dromm’s Immigration Law: Know Your Rights - 6:00pm (P.S. 69Q - 77-02 37th Avenue) Sunday April 9th Palm Sunday Tuesday -

Session 3 12

APPLRG / pteg: Light Rail and the City Regions Day 1 - 27 October 2009 Session 4 – Confederation of Passenger Transport Questions 55 - 67 PLEASE NOTE THIS IS NOT A FULL TRANSCRIPT BUT A NOTE OF THE SESSION. DUE TO A TECHNCIAL FAULT NO TRANSCRIPT IS AVAILABLE. Q55 Paul Rowen: Welcomed panel back after lunch. Asked witnesses to identify themselves and offer any opening statement. David Walmsley: Introduced work of Confederation of Passenger Transport and the role of the Fixed Track Executive. Gave a brief overview of his experience. Drew attention to the fact that CPT represents all of the operators for tram systems in the UK, as well as DLR, Tyne & Wear Metro and Glasgow Subway. Geoffrey Claydon: Introduced himself – ex-government lawyer with experience of working in Department for Transport (and previous incarnations). David Walmsley: CPT has represented LRT interests to government at many levels and worked formally and informally with DfT to improve regulations and so forth. Set out main advantages of light rail – speed, capacity, segregation, smoother ride and modal shift. Indicated that trams do cost a lot of money and therefore it is proper to have good value for money assessments. However trams in UK do cost more and take longer to develop than elsewhere. This was a consequence of the use of heavy rail standards for light rail, lack of continuity and having to go back to square 1 for each scheme, and a contractual process which is seen to add cost. Q56 Paul Rowen: What is the practical contribution that the private sector can bring? David Walmsley: Operators are mostly bus companies as well as LRT operators. -

Appendix B Route Profiles LOCAL/LIMITED BUS ROUTES

Appendix B Route Profiles LOCAL/LIMITED BUS ROUTES GREEN BUS LINES Route Q6 Sutphin Boulevard This arterial route provides local north/south service between Jamaica and John F. Kennedy International Airport connecting the neighborhoods of Jamaica and South Jamaica. The Q6 primarily utilizes Sutphin Boulevard and Rockaway Boulevard to provide local corridor service to the residential neighborhoods along these two commercial arterials. It operates between the Halmar Perishable Center (US Customs, Building 77) at JFK Airport and the 165th Street Bus Terminal in Jamaica. This area of JFK lodges airport services, facilities, and cargo buildings. During peak periods additional service is provided between Sutphin Boulevard/Rockaway Boulevard in South Jamaica and the 165th Street Bus Terminal in Jamaica. Connections are made to the E,J,Z New York City Transit subway lines (Jamaica Center and Sutphin Boulevard stations) in Jamaica as well as the Long Island Railroad Jamaica Station. Transfer to other bus routes is provided at the 165th Street Bus Terminal and along Archer and Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica. Operators of these connecting bus routes include New York City Transit, Long Island Bus, Green Bus Lines, Jamaica Buses, and Queens Surface Corp. The Q6 provides service to important trip generators in Jamaica such as Mary Immaculate Hospital and York College in addition to the Jamaica Arts Center, Queens Central Library, and the Queens County Courthouse. The Q6 provides service seven days a week and 24 hours a day. Headways range from 3 minutes during the weekday peak period to 20 and 35 minutes during weekday evening and overnight periods. -

Waiting and Watching

Waiting and Watching Results of the New York City Transit Riders Council Bus Service and Destination Signage Survey February 2007 Introduction The members of the New York City Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) maintain a keen interest in bus and subway operations and use both services extensively. Over the years the NYCTRC has conducted several surveys to monitor bus service. The members have conducted these studies in response to bus service that does not adequately serve transit users’ needs. One of the major complaints of bus riders is that they do not find service to be reliable. Many bus riders complain to the Council that a long wait for service, followed by several buses in quick succession, is a frequent experience. As a result the NYCTRC addressed the problems of bus bunching and unacceptable waiting times between buses in this project. In this survey, the Council members collected arrival and departure times for each bus observed at a survey point. This information allowed us to calculate headways, or the period of time between consecutive buses serving the same route recorded at a given point, for most of the bus runs observed and to make comparisons between actual and scheduled headways. The comparison between actual and scheduled headways was used as an indicator of correct spacing of buses. This indicator is different from a measure of schedule adherence, in which we would have collected run numbers of buses observed and matched them to schedule information. We chose to use the headway comparison rather than schedule adherence in our analysis because riders are primarily concerned with having a bus available at a stop within a given period of time and are less concerned whether a particular bus is operating according to its schedule.