MDL 875 Plaintiff, : : Transferred from the : Northern District of V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

Car Owner's Manual Collection

Car Owner’s Manual Collection Business, Science, and Technology Department Enoch Pratt Free Library Central Library/State Library Resource Center 400 Cathedral St. Baltimore, MD 21201 (410) 396-5317 The following pages list the collection of old car owner’s manuals kept in the Business, Science, and Technology Department. While the manuals cover the years 1913-1986, the bulk of the collection represents cars from the 1920s, ‘30s, and 40s. If you are interested in looking at these manuals, please ask a librarian in the Department or e-mail us. The manuals are noncirculating, but we can make copies of specific parts for you. Auburn……………………………………………………………..……………………..2 Buick………………………………………………………………..…………………….2 Cadillac…………………………………………………………………..……………….3 Chandler………………………………………………………………….…...………....5 Chevrolet……………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chrysler…………………………………………………………………………….…….7 DeSoto…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Diamond T……………………………………………………………………………….8 Dodge…………………………………………………………………………………….8 Ford………………………………………………………………………………….……9 Franklin………………………………………………………………………………….11 Graham……………………………………………………………………………..…..12 GM………………………………………………………………………………………13 Hudson………………………………………………………………………..………..13 Hupmobile…………………………………………………………………..………….17 Jordan………………………………………………………………………………..…17 LaSalle………………………………………………………………………..………...18 Nash……………………………………………………………………………..……...19 Oldsmobile……………………………………………………………………..……….21 Pontiac……………………………………………………………………….…………25 Packard………………………………………………………………….……………...30 Pak-Age-Car…………………………………………………………………………...30 -

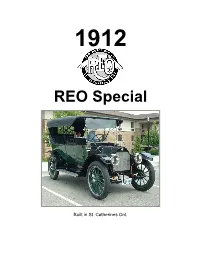

REO and the Canadian Connection

1912 REO Special Built in St. Catherines Ont. Specifications 1912 REO Body style 5 passenger touring car Engine 4 cylinder "F-Head" 30-35 horsepower Bore & Stroke: 4 inch X 4 ½ inches (10 cm X 11.5 cm) Ignition Magneto Transmission 3 speeds + reverse Clutch Multiple disk Top speed 38 miles per hour (60 k.p.h.) Wheelbase 112 inches (2.8 metres) Wheels 34 inch (85 cm) demountable rims 34 X 4 inch tires (85 cm X 10 cm) Brakes 2 wheel, on rear only 14 inch (35 cm) drums Lights Headlights - acetylene Side and rear lamps - kerosene Fuel system Gasoline, 14 gallon (60 litre) tank under right seat gravity flow system Weight 3000 pounds (1392 kg) Price $1055 (U.S. model) $1500 (Canadian model) Accessories Top, curtains, top cover, windshield, acetylene gas tank, and speedometer ... $100 Self-starter ... $25 Features Left side steering wheel center control gear shift Factories Lansing, Michigan St. Catharines, Ontario REO History National Park Service US Department of the Interior In 1885, Ransom became a partner in his father's machine shop firm, which soon became a leading manufacturer of gas-heated steam engines. Ransom developed an interest in self- propelled land vehicles, and he experimented with steam-powered vehicles in the late 1880s. In 1896 he built his first gasoline car and one year later he formed the Olds Motor Vehicle Company to manufacture them. At the same time, he took over his father's company and renamed it the Olds Gasoline Engine Works. Although Olds' engine company prospered, his motor vehicle operation did not, chiefly because of inadequate capitalization. -

QMC US ARMY Hystory Following the End of World War One in 1919, The

QMC US ARMY Hystory Following the end of World War One in 1919, the U.S. military was demobilized. With numerous states requesting surplus military trucks for road work, Congress sold over 90,000 trucks at bargain prices, leaving the U.S. Army with less than 30,000 trucks by 1921. The U.S. Army was facing a serious problem. The trucks that Congress allowed them to retain were wearing out quickly, and no funding was being authorized to purchase new units. And importantly in the Army’s mind, most of their remaining trucks were essentially 4x2 MILCOTS (military commercial off-the-shelf), trucks that had no tactical cross-country capability. An effort had been made to update World War One Standard B “Liberty” trucks to a more modern “3rd series” specification, but they remained obsolete in design and the conversion rate was too low. In 1920, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Depot at Fort Holabird, Maryland began assembling cross-country vehicles and evaluating their performance. For the most part, components from existing vehicles were used. At Fort Holabird, Army Captain and Chief Engineer Arthur W. Herrington realized that his people could develop and produce purpose-designed high performing cross-country trucks at substantially lower costs than what the automakers were charging the Army for their commercial trucks. Though the automakers were anxious to profit from Army truck sales, few were building a suitable modern truck with all-wheel drive, particularly in the Army’s high volume one to three ton range. In 1928, U.S. Army automotive engineers at Fort Holabird began work on prototypes that would lead to a range of trucks from a 1-1/4 ton 4x4 to a 12 ton 6x6. -

A Trio of Stunning Stutz Automobiles Owned By: Fountainhead Antique Automobile Museum Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA

Winter 2015 1918 Stutz Bulldog A Trio of Stunning Stutz Automobiles Owned by: Fountainhead Antique Automobile Museum Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA PNR-CCCA and Regional Events 2016 CCCA National Events Details can be obtained by contacting the Event Annual Meeting Manager. If no event manager is listed, contact the sponsoring organization. January 14-17 ...................Novi, MI Grand Classics® January 23rd - 30th -- Arizona Concours February 21 ...........Southern Florida Region PNR Contact: Val Dickison March 11 - 13 ..........San Diego/Palm Springs April 9th -- Coming-Out Party June 3 - 5 ...........CCCA Museum Experience PNR Contacts: Gary Johnson, Bill Deibel, Stan Dickison CARavans May 1st -- HCCA Tour April 23 - May 1 ........... North Texas Region September 9-17 ...........New England Region May 7th -- South Prairie Fly-In PNR Contact: Bill Allard May 14th -- Picnic at Sommerville's Director's Message The Last Rohrback Director Comments! PNR Contact: Dennis Somerville 2015 is now in the June 19th -- Father's Day Classics at the Locks bag and I think it was a great year for car July 4th -- Yarrow Point 4th of July Parade events big and small. I PNR Contact: Al McEwan really have a lot of fun tooling around in my August 8th -- Motoring Classic Kick-Off Classic and enjoying at Peter Hageman's Firehouse the company of the finest people in the world. Our club is simply awesome and I have had the opportunity to September 3rd -- Crescent Beach Concours be directly involved with a couple of Grand Classics, a PNR Contacts: Laurel & Colin Gurnsey series of Concours events, two Coming Out Parties (My Favorite: thank you, Gary Johnson), and all the diverse September 9th -- Tour du Jour activities that have been planned by Managers and other Contact: America's Car Museum members. -

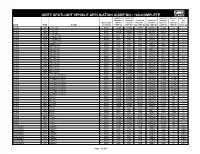

Unity Spotlight Vehicle Application Guide No.: 168

UNITY SPOTLIGHT VEHICLE APPLICATION GUIDE NO.: 168-COMPLETE 600000 CP 245000 CP 100000 CP INST KIT INST KIT CHROME 6 *CHROME 160000 CP 100000 CP CHROME LH RH MOUNTING DIA HID 6 DIA H3 *CHROME 6 CHROME 5 4X6 RECT DRIVERS PASS MAKE YEAR MODEL LOCATION PART NO PART NO DIA PART NO DIA PART NO PART NO PART NO PART NO ACURA 2003 CL (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2002 CL (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2001 CL (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2000 CL COUPE (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 189 ----- ACURA 1999 CL COUPE (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 189 ----- ACURA 1998 CL COUPE (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 189 ----- ACURA 1997 CL COUPE (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 189 ----- ACURA 2001 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 2000 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 1999 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 1998 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 1997 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 1996 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 1995 INTEGRA (22) POST 340V 330V 325V 250V-H 264V 208 ----- ACURA 2006 MDX (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2005 MDX (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2004 MDX (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2003 MDX (15) (22) POST 340GM 330GM 325GM 250GM-H 264GM 189 ----- ACURA 2002 MDX -

Structural Change and Product Differentiation in the Heavy-Truck

WORKING PAPERS STRUCTURAL CHANGE AND PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION IN THE HEAVY-TRUCK MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY, 1947-1971 David F. Lean WORKING PAPER NO. 4 March 1977 fl'CBureau of Economics working papersare preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment All data contained in themare in the public domain. This includes information obtained by the Commission which has become part ofpublic record. The analyses and conclusionsset forth are those ofthe authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of other members ofthe Bureau of Economics,other Commission staff, or the Commission itself. Upon request,single copies ofthe paper will be provided. Referencesin publications to FfCBureau of Economics working papers by FfC economists(other than acknowledgementby a writer that he has access to such unpublished materials) should be cleared with the author to protect the tentative characterof these papers. BUREAUOF ECONOMICS FEDERALTRADE COMMISSION WASHINGTON,DC 20580 Introduction Economists generally associate producer goods' industries with negligible degrees of product differentiation. Such perceptions are derived partly from apparent physical homogeneities of goods, and partly from evidence of low advertising to sales ratios, an often used cri terion of the degree of product differentiation. Because higher levels of product differentiation are generally associated with consumer goods' industries, the producer good-consumer good dichotomy has been used in some studies to help discern the influence of product differentiation on market structure and industry performance. (See for example, Mueller and Hamm [15]; Rhoades and Cleaver [18]; and Strickland and Weiss [23]). Despite general presumptions, however, some producer goods' in dustries exhibit high degrees of product differentiation. 11 Heavy-truck manufacturing is a case in point, and the substantial increase in concentration that has occurred in this industry over the post World War II period may be attributed partly to product differentiation forces. -

REO Motor Company Records

REO Motor Company Records http://archives.msu.edu/findaid/036.html SUMMARY INFORMATION Repository Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections Creator Reo Motor Car Company. Title REO Motor Car Company records ID 00036 Date [inclusive] 1904-1976 Extent 170.0 Cubic feet 170 cu ft , 283 volumes HISTORICAL NOTE Both the beginning and end of the REO company occurred amid controversy. The firm was incorporated on August 16, 1904 by R.E. Olds and other investors as the R.E. Olds Company. It quickly passed through several name changes and permutations. On May 30, 1975 the firm, then known as Diamond REO Trucks, Inc., filed for bankruptcy. Ransom Eli Olds, founder of the Olds Motor Works (later the Oldsmobile Division of General Motors), was forced out of that firm in 1902. Two years later, Olds and other investors formed the R.E. Olds Co. to manufacture automobiles. Following a legal threat from the Olds Motor Works, the R.E. Olds Company's name was changed to the REO Car Company (which later became the REO Motor Car Company). On October 8, 1910 the investors also formed the REO Motor Truck Company to manufacture trucks, eventually known as "speedwagons." This firm was combined with the REO Motor Car Company on September 29, 1916. During 1919 the firm sold more trucks than cars for the first time, and continued to do so until 1936. In that year car production was halted due to losses from declining sales which were caused by the Great Depression. The firm was reorganized in 1938 as REO Motors, Inc. -

Trucks for 1945 White

54 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS 1944 ALMANAC EDITION TRUCKS FOR 1945 WHITE 20,000 Light Trucks OK'd For First Half of '45 Seven truck manufacturers have been authorized to build 20,000 light trucks under 9,000 pound rating, during the first six months of 1945. These have been allotted on a historical basis as follows: Chevrolet 6,719, Dodge 3,259, Ford 6,287, International Harvester 2,457, General Motors Truck 1,097, Willys 112 and Diamond T 99. Due to the small number of vehicles allotted each manufacturer, it is ex- pected that most of the trucks produced in this category will be one-half ton pick-up models, since these take less press work and set-up time. WHITE OFFERS four trucks and two but modolt for 1945 civilian uto. Modol WA-14, tho modium vehicle in tho lino carrios a GVW rating of 14,000-15,000 pounds with a 2SO cubic inch ongino, fivo-tpood transmission and whoolbatos from 136 inchos to 214 inches. n. •;,. -.?v i*--» B ¦?•¦ ' •"*! Jttaril MARMON-HERRINGTON iMTi t. ¦ L i jtA* MODEL WA 20 civilian 1945 White carrios an It .000 19,000 pound GVW rating, it standard with a 318 cubic inch ongino, fivo-tpood transmission and comes in whoolbatos from 136 inchos to 226 inchos. <^ruw . ' ii •. v'*v -'^h-V'f’-yfS'if -i.i.iv?: /•£ - V- * .tji \» '%>¦ *• ¦» *Frwx.J5* «r* r* «J*>i. 3r i«mii*^-svS3ff^v ¦ - * 'v »•**¦’ a:'" ’, V- "**• *»" MAR MON HERRINGTON has boon to lOadod with war work that it hat not boon given any now truck allotmont for 1945, but is allowod to mako four and six-wheel drive conversions of Ford civilian truck*. -

CAT Scale Super Trucks Collector Cards: Series 3

CAT Scale Super Trucks ® Collector Cards: Series 3 CAT Scale’s Series Three Super Trucks® Limited Edition collector cards were randomly distributed on CAT Scale weigh tickets in 1997 & 1998. The cards were attached directly to the weigh tickets so each time a driver weighed, a Series Three collector card was automatically received. There are 60 different cards in all! Card # Year Make Model Engine Transmission 1 1996 Freightliner Classic XL 500 Cummins 18 Speed 2 1986 Peterbilt 359 425 CAT Spicer 6X4 3 1994 Kenworth K100E 430 Detroit 13 Speed 4 1997 Peterbilt 379 500 hp Super 10 5 1997 Kenworth W900L CAT 550 hp 18 Speed 6 1996 Kenworth W900L 500 hp 13 Speed 7 1995 Freightliner FLD-120 470 hp 13 Speed 8 1998 Peterbilt 379 475 CAT 18 spd 9 1969 Peterbilt 359A Cummins 8500 Frt. 10 1972 Peterbilt 359A CAT 425 hp 13 Speed 11 1975 Dodge 950 Big Horn 350 Cummins 13 Speed 12 1952 Mack LTLSW Cummins 290 hp 5X3 13 1972 Peterbilt 359 NTC 400 Cummins Allison Auto 14 1954 GMC 950 G-71 GM 10 Speed 15 1919 Ford TT 4 cyl Ford 2 Speed 16 1922 White 3/4 Ton 4 cyl 22.5 hp 4 Speed 17 1997 Kenworth T-600-B CAT 475 hp 18 Speed 18 1995 Kenworth W900L 550 hp 15 Speed 19 1995 Peterbilt 379 425 hp 15 Speed 20 1996 Freightliner Classic Detroit 500 hp 13 Speed 21 1997 Peterbilt 379 CAT 550 hp 18 Speed 22 1990 Peterbilt 379 Hood Twin Turbo 'B' CAT 15 Speed 23 1996 Kenworth W900L Cummins Super 13 24 1995 Peterbilt 379 Ex Hood CAT 450 hp 15 Speed 25 1969 Peterbilt M-359 400 Big Cam 13 Speed 26 1963 International Cab-over Cummins 335 13 spd 27 1956 Mack B73LS Cummins -

MINUTES of the LOUISIANA MOTOR VEHICLE COMMISSION 3519 12Th Street Metairie, Louisiana 70002 Monday, January 6, 2020

MINUTES OF THE LOUISIANA MOTOR VEHICLE COMMISSION 3519 12th Street Metairie, Louisiana 70002 Monday, January 6, 2020 The meeting was called to order at 10:05 a.m. by Acting Chairman Allen O. Krake. Present were: Acting Commissioner Allen O. Krake Commissioner V. Price LeBlanc, Jr. Commissioner Gregory Lala Commissioner Harold H. Perrilloux Commissioner Eric R. Lane Commissioner Stephen L. Guidry, Jr. Commissioner Kenneth “Mike” Smith Commissioner Keith P. Hightower Commissioner Keith M. Marcotte Commissioner Randy Scoggin Commissioner Joseph W. “Bill” Westbrook Commissioner Donna S. Corley Commissioner Maurice C. Guidry L. A. House, Executive Director Adrian F. LaPeyronnie, III, Counselor Gregory F. Reggie, Counselor Burgess E. McCranie, Jr., Counselor Absent were: Commissioner Terryl J. Fontenot ***************************************************** Also, in attendance were Will Green, President of the Louisiana Automobile Dealers Association and Jeanne C. Comeaux, Esq. with Breazeale, Sachse & Wilson, L.L.P.; and Commission staff: Ingya Cattle, Assistant Executive Director; Scott Landreneau, Commission Investigator Supervisor; Commission Investigators: Neil Rogers, Antoine Derouen, Kevin Broussard, Ben Guidry, Angel Blackford, and Monica Wells; Stacey Broussard, Administrative Coordinator Supervisor; and Administrative Coordinators: Trina Adams and Leotine Benoit; and Tim Knotts, Assistant. ***************************************************** The Acting Chairman Krake called for a moment of silence in memory of Chairman Ray Brandt. ***************************************************** The Acting Chairman Krake called to order Hearing #2019-084, Kangacruz for the denial of a recreational products dealer application. Representing Premier Farm & Ranch Supply, L.L.C. DBA Premier Farm & Ranch Supply was: Scott W. Esthay, owner. A court reporter was brought in to record the transcript of the hearing, which will be made a permanent part of the Commission’s files. -

Tsooys Sf M0TX$E P Ruelle, INC

tsOOYS sf M0TX$E P P.O. Box 1540, Willis CA 95490 volu[UtE 2r N0 2 NEWSlETTER AUGUSI 2OO3 ffiw RUEllE, INC. The story of C.V."Vir" Ruelle begins on poge 5 ROOTS BOARD OT DIRECTOR'S MEffIilGS The Roots Board of Directors, at their January Meeting, established a regular schedule of meetings for the rest of 2003. Meetings will be held the second Thursday of odd numbered months. Beginning in July, meetings will be held at the Roots office in the new exhibition building next to the museum. Meetings are scheduled to begin at 6:00 PM. Here is the schedule for the rest of the year: September 11 November 13 Members and volunteers are welcome to attend these meetings. COVER PH0I0: Vic Ruelle's new 1947 Kenworth delivers Santa Claus to the Irving & Muir Building on Main St. in Willits in December,1947. Dobe Hardaway is the driver. See Page 5. R00rs 0t flloilvE PoWER, ll{c. 2002-2003 This newsl-etter is the offi- Officers ond Boord of Directors cial publ-ication of Roots Of Mot.ive Power, Inc., an organi-- President ---- ChrisBaldo zation dedicated to the preser- Viee President Wes Brubacher vation and restoration of log- Seeretary - Joan l)aniels ging and rail-road equipment representative of California's Corr. Seeretary Dian Crayne North Coast regj-on, 1850s to Tbeasurer/I)irector - Chuek CraJrne t.he present. Membership $25.00 Librarian/I)ireetor - - Bruee Evans annually; Regular members vote I)ireetor --l'rainConley for officers and Directors who I)ireetor --KirkGraux decide the general policy and I)ireetor - George Bush direction for the association.