Fumigant Toxicity of Essential Oils to Reticulitermes Flavipes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patchouli Essential Oil Extracted from Pogostemon Cablin (Blanco) Benth

Advances in Environmental Biology, 8(7) May 2014, Pages: 2301-2309 AENSI Journals Advances in Environmental Biology ISSN-1995-0756 EISSN-1998-1066 Journal home page: http://www.aensiweb.com/aeb.html Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Patchouli Essential Oil Extracted From Pogostemon cablin [Blanco] Benth. [lamiaceae] Ahmad Karimi Ph.D. in pharmacy, University of Santo Tomas, Philippines ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The physico-chemical properties of Philippine patchouli oil, hydro-distilled from fresh Received 25 March 2014 leaves and young shoots of Pogostemon cablin were characterized and found to be Received in revised form 20 April within the specifications set by the United States Essential Oils Society. Philippine 2014 patchouli oil and commercial patchouli oil have the same major components as shown Accepted 15 May 2014 by GC-MS analyses: patchouli alcohol, d-guaiene, a-guaiene, a-patchoulene, Available online 10 June 2014 seychellene, [3-patchoulene, and transcaryophylene, with slightly lower concentrations in the Philippine oil. Using the disk diffusion method patchouli oil was found to be Key words: active against the gram-positive bacteria: Staphylococcus, Bacillus, and Streptococcus Pogostemon cablin, patchouli oil, species. Fifty five percent [11/20] of community and only 14.8% [9/61] of hospital- essential oil, antimierobial activity, Staphylococcus aureus isolates were susceptible to an MIC of 0.03% [v/v.] and Sixty- physico-chemical properties four percent or 23/36 of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] isolates was sensitive to patchouli oil at 0.06%, as opposed to only 44% or 11/25 of the sensitive strains. Philippine patchouli essential oil was also active against several dermatophytes at 0.25%. -

In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of 34 Plant Essential Oils Against Alternaria Alternata

E3S Web o f Conferences 136, 06006 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20191360 6006 ICBTE 2019 In vitro antibacterial activity of 34 plant essential oils against Alternaria alternata Qiyu Lu1, Ji Liu2, Caihong Tu2, Juan Li3, Chunlong Lei3, Qiliang Guo2, Zhengzhou Zhang2, Wen Qin1* 1College of Food Science and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University, Ya'an, Sichuan, 625014, China 2Institute of Food Science and Technology, Chengdu Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Science, Chengdu, Sichuan, 611130, China 3 Institute of Animal Science, Chengdu Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Science, Chengdu, Sichuan, 611130, China Abstract. To determine the antibacterial effect of 34 plant essential oils on Alternaria alternata, 34 plant essential oils such as asarum essential oil, garlic essential oil, and mustard essential oil are used as inhibition agents to isolate A. alternata from citrus as indicator bacteria, through the bacteriostasis test and drug susceptibility test, the types of essential oils with the best inhibitory effect were screened and their concentration was determined. The results showed that the best inhibition effect was mustard essential oil with a minimum inhibitory concentration of 250 μl/L and a minimum bactericidal concentration of 250 μl/L. Followed by the Litsea cubeba essential oil and basil oil, the minimum inhibitory concentration is 500 μl/L. 1 Introduction quality and safety. A. alternata is the main fungus causing post-harvest disease of Pitaya, and the Citrus is a general term for orange, mandarin, orange, antibacterial effect of using cinnamon oil and clove oil is kumquat, pomelo, and medlar. Citrus is the world's good [10]. Clove oil can effectively inhibit the growth of largest fruit, rich in sugar, organic acids, mineral A. -

Herbs, Spices and Essential Oils

Printed in Austria V.05-91153—March 2006—300 Herbs, spices and essential oils Post-harvest operations in developing countries UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Telephone: (+43-1) 26026-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26926-69 UNITED NATIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURE E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.unido.org INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION OF THE ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS © UNIDO and FAO 2005 — First published 2005 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: - the Director, Agro-Industries and Sectoral Support Branch, UNIDO, Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria or by e-mail to [email protected] - the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Development of Process for Purification of Α and Β-Vetivone from Vetiver Essential Oil & Investigation of Effects of Heavy

UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES PhD Thesis Proposal Development of process for purification of α and β-vetivone from Vetiver essential oil & Investigation of effects of heavy metals on quality and quantity of extracted Vetiver oil Thai Danh Luu {B. Agric. Sc. (Qld University, Australia), M. Sc. (VUB, Belgium)} School of Chemical Sciences and Engineering Unversity of New South Wales, Sydney 1 Supervisor: Prof Neil Foster Supervisor: Prof Neil Foster Co-supervisors: Prof Tam Tran 2 and Dr Paul Truong 3 1 School of Chemical Sciences and Engineering, UNSW 2 Division of Engineering, Science and Technology, UNSW-Asia 3 Veticon Consulting and International Vetiver Network, Brisbane 1 I. INTRODUCTION In recent years, there is an increasing trend in research of essential oils extracted from various herbs and aromatic plants due to the continuous discoveries of their multifunctional properties other than their classical roles as food additives and/or fragrances. New properties of many essential oils, such as antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities have been found and confirmed (Aruoma et al, 1996; Hammer et al, 1999; Güllüce et al, 2003). The pharmacological properties of essential oils extracted from plants have received the greatest interest of academic institutes and pharmaceutical companies (Ryman, 1992; Loza- Tavera, 1999; Courreges et al, 2000; Carnesecchi et al, 2002 and Salim et al, 2003). On the other hand, the insecticidal activities of essential oils are more favored by agricultural scientists and agri-business. Consequently, many investigation and new findings have significantly prompted and expanded novel applications of essential oils which are now been widely used as natural insecticides, cosmeceuticals, and aroma therapeutic agents. -

Master Plant List 2017.Xlsx

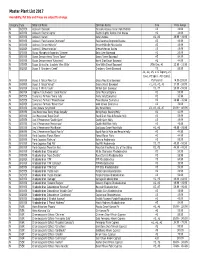

Master Plant List 2017 Availability, Pot Size and Prices are subject to change. Category Type Botanical Name Common Name Size Price Range N BREVER Azalea X 'Cascade' Cascade Azalea (Glenn Dale Hybrid) #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Electric Lights' Electric Lights Double Pink Azalea #2 44.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Karen' Karen Azalea #2, #3 39.99 - 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Poukhanense Improved' Poukhanense Improved Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Renee Michelle' Renee Michelle Pink Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Stewartstonian' Stewartstonian Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Buxus Microphylla Japonica "Gregem' Baby Gem Boxwood #2 29.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Green Tower' Green Tower Boxwood #5 64.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Katerberg' North Star Dwarf Boxwood #2 44.99 N BREVER Buxus Sinica Var. Insularis 'Wee Willie' Wee Willie Dwarf Boxwood Little One, #1 13.99 - 21.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Cranberry Creek' Cranberry Creek Boxwood #3 89.99 #1, #2, #5, #15 Topiary, #5 Cone, #5 Spiral, #10 Spiral, N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Mountain' Green Mountain Boxwood #5 Pyramid 14.99-299.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Velvet' Green Velvet Boxwood #1, #2, #3, #5 17.99 - 59.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Winter Gem' Winter Gem Boxwood #5, #7 59.99 - 99.99 N BREVER Daphne X Burkwoodii 'Carol Mackie' Carol Mackie Daphne #2 59.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Ivory Jade' Ivory Jade Euonymus #2 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Moonshadow' Moonshadow Euonymus #2 29.99 - 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Rosemrtwo' Gold Splash Euonymus #2 39.99 N BREVER Ilex Crenata 'Sky Pencil' -

Active Metabolites of the Genus Piper Against Aedes Aegypti: Natural Alternative Sources for Dengue Vector Control

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (1): 61-82 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-1.amgp Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Active metabolites of the genus Piper against Aedes aegypti: natural alternative sources for dengue vector control André M. Marques1 , Maria Auxiliadora C. Kaplan Abstract The mosquito, Aedes aegypti, is the principal vector of the viruses responsible for dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fevers. The mosquito is widespread throughout tropical and sub-tropical regions; its prevalence makes dengue one of the most important mosquito-borne viral diseases in the world occurring annually in more than 100 endemic countries. Because blood is essential to their development cycle, the Aedes species maintains a close association with humans and their dwellings. Fittingly, the most widely adopted strategy to decrease the incidence of these diseases is the control of the mosquito larvae population. The emergence of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes has amplified the interest in finding natural products effective againstAedes aegypti adults, as well as larvae. Plant- derived compounds have played an important role in the discovery of new active entities for vector management as they are safer and have lower toxicity to humans in comparison to conventional insecticides. This review assesses a naturally occurring plant matrix and pure compounds of the Piper species, which have been shown to be active against Aedes aegypti. Keywords: dengue; Aedes aegypti; Piper; Piperaceae; larvicidal metabolites; tropical diseases. Introduction Edited by Alberto Acosta Dengue: an emerging disease in the world 1. Instituto de Pesquisas de Produtos Naturais (IPPN), Centro de Dengue is transmitted to humans by the Aedes aegypti Ciências da Saúde, Bloco H - 1º andar, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. -

2018 Spring Perennials List

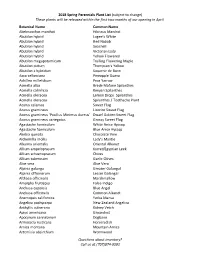

2018 Spring Perennials Plant List (subject to change) These plants will be released within the first two months of our opening in April. Botanical Name Common Name Abelmoschus manihot Hibiscus Manihot Abutilon hybrid Logee's White Abutilon hybrid Red Nabob Abutilon hybrid Seashell Abutilon hybrid Victorian Lady Abutilon hybrid Yellow Flowered Abutilon megapotamicum Trailing Flowering Maple Abutilon pictum Thompson's Yellow Abutilon x hybridum Souvenir de Bonn Acca sellowiana Pineapple Guava Achillea millefolium Proa Yarrow Acmella alba Brede Mafane Spilanthes Acmella calirrhiza Kenyan Spilanthes Acmella oleracea Lemon Drops Spilanthes Acmella oleracea Spilanthes / Toothache Plant Acorus calamus Sweet Flag Acorus gramineus Licorice Sweet Flag Acorus gramineus 'Pusillus Minimus Aureus' Dwarf Golden Sweet Flag Acorus gramineus variegatus Grassy Sweet Flag Agastache foeniculum White Anise Hyssop Agastache foeniculum Blue Anise Hyssop Akebia quinata Chocolate Vine Alchemilla mollis Lady's Mantle Alkanna orientalis Oriental Alkanet Allium ampeloprasum Kurrat/Egyptian Leek Allium schoenoprasum Chives Allium tuberosum Garlic Chives Aloe vera Aloe Vera Alpinia galanga Greater Galangal Alpinia officinarum Lesser Galangal Althaea officinalis Marshmallow Amorpha fruiticosa False Indigo Anchusa capensis Blue Angel Anchusa officinalis Common Alkanet Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa Angelica pachycarpa New Zealand Angelica Anthyllis vulneraria Kidney Vetch Apios americana Groundnut Apocynum cannabinum Dogbane Armoracia rusticana Horseradish Arnica -

Effects of Heartwood Extractives on Symbiotic Protozoan Communities and Mortality in Two Termite Species

International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 123 (2017) 27e36 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ibiod Effects of heartwood extractives on symbiotic protozoan communities and mortality in two termite species * Babar Hassan a, , Mark E. Mankowski b, Grant Kirker c, Sohail Ahmed a a Department of Entomology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan b USDA-FS, Forest Products Laboratory, Starkville, MS, USA c USDA-FS, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, WI, USA article info abstract Article history: Lower termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) are considered severe pests of wood in service, crops and Received 1 November 2016 plantation forests. Termites mechanically remove and digest lignocellulosic material as a food source. The Received in revised form ability to digest lignocellulose not only depends on their digestive tract physiology, but also on the 19 May 2017 symbiotic relationship between termites and their intestinal microbiota. The current study was designed Accepted 19 May 2017 to test the possible effects of four heartwood extractives (Tectona grandis, Dalbergia sissoo, Cedrus deodara and Pinus roxburghii) on the mortality, feeding rate and protozoan population in two lower termites, Reticulitermes flavipes and Heterotermes indicola. All wood extractives tested rapidly lowered protozoan Keywords: Subterranean termites numbers in the hindgut of termite workers, which was closely correlated with worker mortality. The R. flavipes average population of protozoans in both termite species was diminished in a dose-dependent manner H. indicola after fifteen days feeding on treated filter paper. Mortality of termites increased when fed on filter paper Heartwood extractives treated with T. grandis or D. sissoo heartwood extractives with minimum feeding rate at the maximum À Gut protozoa concentration (10 mg ml 1). -

Effect of Orange Oil Extract on the Formosan Subterranean Termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae)

HOUSEHOLD AND STRUCTURAL INSECTS Effect of Orange Oil Extract on the Formosan Subterranean Termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) ASHOK RAINA,1,2 JOHN BLAND,1 MARK DOOLITTLE,3 ALAN LAX,1 3 4 RAJ BOOPATHY, AND MICHAEL FOLKINS J. Econ. Entomol. 100(3): 880Ð885 (2007) ABSTRACT The Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki (Isoptera: Rhinoter- mitidae), accidentally brought into the United States, has become a major urban pest, causing damage to structures and live trees. Because of increasing restrictions on the use of conventional termiticides, attention is focused on Þnding safer alternative methods for termite management. Oil from citrus peel, referred to here as orange oil extract (OOE), contains Ϸ92% d-limonene, and it is generally known to be toxic to insects. In laboratory experiments, 96 and 68% termites were killed in 5 d when OOE at 5 ppm (vol:vol) was dispensed from the top or bottom, respectively, with termites held at the opposite end of a tight-Þtting plastic container. Apart from high mortality, workers exposed to vapor consumed signiÞcantly less Þlter paper than controls. However, when termites were exposed to OOE vapor, even at 10 ppm, in the void of a model wall, there was very little mortality. Termites did not tunnel through glass tubes Þlled with sand treated with 0.2 or 0.4% OOE. Sand treated with OOE was extracted each week for 8 wk to determine the remaining amount of d-limonene. Results indicated that there was a sharp decline in the quantity of d-limonene during the Þrst 3 wk to a residual level that gradually decreased over the remaining period. -

Chemical Composition and Biological Properties of Chrysopogon Zizanioides (L.) Roberty Syn. Vetiveria Zizanioides (L.) Nash- a Review

Indian Journal of Natural Products and Resources Vol. 6(4), December 2015, pp. 251-260 Chemical composition and biological properties of Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty syn. Vetiveria zizanioides (L.) Nash- A Review Khushminder Kaur Chahal, Urvashi Bhardwaj*, Sonia Kaushal and Amanpal Kaur Sandhu Department of Chemistry, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana-141004, Punjab, India Received 1 April 2015; Accepted 18 August 2015 Vetiver [Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty syn. Vetiveria zizanioides (L.) Nash] commonly known as khas-khas, khas, khus-khus or khus grass belongs to the family Poaceae. The roots of this grass on steam distillation yield an essential oil mainly consisting of sesquiterpenes (3-4 %), sesquiterpenols (18-25 %) and sesquiterpenones (7-8 %). Among these, the major economically important active compounds are khusimol, α-vetivone and β-vetivone which constitute about 35 % of oil. The commercial grades, viz. Dharini, Gulabi and Kesari and Pusa Hybrid-7, Hybrid-8, Sugandha, KH-8, KH-40, are available in North India and South India, respectively for commercial cultivation. The insecticidal, antimicrobial, herbicidal and antioxidant activities of essential oil and its components like vetivone, zizanal, epizizanal and nootkatone are well known. This review is an effort to collect all the information regarding chemical composition and biological activities of vetiver oil. Keywords: Biological activities, Chemical composition, Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty, Vetiveria zizanioides (L.) Nash, Vetiver essential oil. IPC code; Int. cl. (2015.01)− A61K 36/00 Introduction khus grass (Hindi), valo (Gujrati), vala (Marathi) is a The essential oils also known as ethereal oils are fast growing perennial grass belonging to family defined as odiferous bodies of an oily nature, obtained Poaceae. -

Building an Octaploid Genome and Transcriptome of the Medicinal Plant

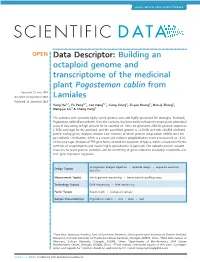

www.nature.com/scientificdata OPEN Data Descriptor: Building an octaploid genome and transcriptome of the medicinal plant Pogostemon cablin from Received: 19 June 2018 Accepted: 21 September 2018 Lamiales Published: 11 December 2018 1 2 3 1 3 1 Yang He ,*, Fu Peng ,*, Cao Deng ,*, Liang Xiong , Zi-yan Huang , Ruo-qi Zhang , 3 1 Meng-jia Liu & Cheng Peng The Lamiales order presents highly varied genome sizes and highly specialized life strategies. Patchouli, Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. from the Lamiales, has been widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical areas of Asia owing to high demand for its essential oil. Here, we generated ~681 Gb genomic sequences (~355X coverage) for the patchouli, and the assembled genome is ~1.91 Gb and with 110,850 predicted protein-coding genes. Analyses showed clear evidence of whole-genome octuplication (WGO) since the pan-eudicots γ triplication, which is a recent and exclusive polyploidization event and occurred at ~6.31 million years ago. Analyses of TPS gene family showed the expansion of type-a, which is responsible for the synthesis of sesquiterpenes and maybe highly specialization in patchouli. Our datasets provide valuable resources for plant genome evolution, and for identifying of genes related to secondary metabolites and their gene expression regulation. phylogenetic analysis objective • replicate design • sequence assembly Design Type(s) objective Measurement Type(s) whole genome sequencing • transcriptional profiling assay Technology Type(s) DNA sequencing • RNA sequencing Factor Type(s) Read Length • biological replicate Sample Characteristic(s) Pogostemon cablin • root • stem • leaf 1 State Key Laboratory Breeding Base of Systematic Research, Development and Utilization of Chinese Medicine 2 Resources, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, 610075, China. -

Agastache Rugosa Alleviates the Multi-Hit Effect on Hepatic Lipid Metabolism, Infammation and Oxidative Stress During Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Agastache rugosa alleviates the multi-hit effect on hepatic lipid metabolism, inammation and oxidative stress during nonalcoholic fatty liver disease Yizhe Cui Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7877-8328 Renxu Chang Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University Qiuju Wang Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University Yusheng Liang University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Juan J Loor University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Chuang Xu ( [email protected] ) Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University Research Keywords: NAFLD, Agastache rugosa, mice, AML12 cells, multi-targets Posted Date: April 21st, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-21957/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/24 Abstract Background Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease, and has high rates of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Agastache rugosa (AR) possesses unique anti-oxidant, anti‐inammatory and anti-atherosclerosis characteristics. Methods To investigate the effects and the underlying mechanism of AR on NAFLD, we fed mice a high-fat diet (HFD) to establish NAFLD model of mice in vivo experiment and induced lipidosis in AML12 hepatocytes through a challenge with free fatty acids (FFA) in vitro. The contents of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in liver homogenates were measured. Pathological changes in liver tissue were evaluated by HE staining. Oil red O staining was used to determine degree of lipid accumulation in liver tissue, and Western blot was used to detect abundance of inammation-, lipid metabolism- and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins.