Half – Living Between Two Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir

Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Morgan Balfour (San Francisco) soprano 2019 Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Brandenburg Choir SYDNEY Matthew Manchester Conductor City Recital Hall Paul Dyer AO Artistic Director, Conductor Saturday 14 December 5:00PM Saturday 14 December 7:30PM PROGRAM Wednesday 18 December 5:00PM Mendelssohn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Wednesday 18 December 7:30PM Anonymous Sonata à 9 Gjeilo Prelude MELBOURNE Eccard Ich steh an deiner Krippen hier Melbourne Recital Centre Crüger Im finstern Stall, o Wunder groβ Saturday 7 December 5:00PM Palestrina ‘Kyrie’ from Missa Gabriel Archangelus Saturday 7 December 7:30PM Arbeau Ding Dong! Merrily on High Handel ‘Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion’ NEWTOWN from Messiah, HWV 56 Friday 6 December 7:00PM Head The Little Road to Bethlehem Gjeilo The Ground PARRAMATTA Tuesday 10 December 7:30PM Vivaldi La Folia, RV 63 Handel Eternal source of light divine, HWV 74 MOSMAN Traditional Deck the Hall Wednesday 11 December 7:00PM Traditional The Coventry Carol WAHROONGA Traditional O Little Town of Bethlehem Thursday 12 December 7:00PM Traditional God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen Palmer A Sparkling Christmas WOOLLAHRA Adam O Holy Night Monday 16 December 7:00PM Gruber Stille Nacht Anonymous O Come, All Ye Faithful CHAIRMAN’S 11 Proudly supporting our guest artists. Concert duration is approximately 75 minutes without an interval. Please note concert duration is approximate only and subject to change. We kindly request that you switch off all electronic devices prior to the performance. This concert will be broadcast on ABC Classic on 21 December at 8:00PM NOËL! NOËL! 1 Biography From our Principal Partner: Macquarie Group Paul Dyer Imagination & Connection Paul Dyer is one of Australia’s leading specialists On behalf of Macquarie Group, it is my great pleasure to in period performance. -

Koorie Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: January - February 2021

Koorie perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: January - February 2021 This edition of the Koorie enrich your teaching program, see VAEAI’s Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin Protocols for Koorie Education in Primary and features: Secondary Schools. For a summary of key Learning Areas and − Australia Day & The Great Debate Content Descriptions directly related to − The Aboriginal Tent Embassy Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories − The 1939 Cummeragunja Walk-off & and cultures within the Victorian Curriculum F- Dhungala – the Murray River 10, view or download the VCAA’s curriculum − Charles Perkins & the 1967 Freedom guide: Learning about Aboriginal and Torres Rides Strait Islander histories and cultures. − Anniversary of the National Apology − International Mother Language Day January − What’s on: Tune into the Arts Welcome to the first Koorie Perspectives in Australia Day, Survival Day and The Curriculum Bulletin for 2021. Focused on Great Debate Aboriginal Histories and Cultures, we aim to highlight Victorian Koorie voices, stories, A day off, a barbecue and fireworks? A achievements, leadership and connections, celebration of who we are as a nation? A day and suggest a range of activities and resources of mourning and invasion? A celebration of around key dates for starters. Of course any of survival? Australians hold many different views these topics can be taught at any time on what the 26th of January means to them. In throughout the school year and we encourage 2017 a number of councils controversially you to use these bulletins and VAEAI’s Koorie decided to no longer celebrate Australia Day Education Calendar for ongoing planning and on this day, and since then Change the Date ideas. -

VIBE ACTIVITIES Issueyears 186 3-4

Years 3-4 Y E A R Name: 3-4 VIBE ACTIVITIES IssueYears 186 3-4 The 2012 Deadlys – Female Artist of the Year page 7 JESS BECK JESSICA MAUBOY FEMALE ARTIST Originally hailing from Mingbool (near Mt Jessica Mauboy first graced Australian Gambier, SA), Jess drifted into singing while television as a shy 16 year old on studying acting at Adelaide University, Australian Idol in 2006. She was runner- OF THE YEAR but she admits music was always her first up that season, but was subsequently love. Jess wanted to be a performer from signed to Sony Music Australia. In an early age. While studying a Bachelor of February 2007 she released her debut Rainmakers with Neil Murray, founder of Creative Arts (Acting) at Flinders University, LP, The Journey, and in 2008, recorded the Warumpi Band. Following her recording Adelaide, she developed an interest in jazz her album Been Waiting which achieved debut on the Paul Kelly single Last Train, and cabaret. She auditioned for a band, double platinum sales, garnered seven Anu’s debut album Stylin’ Up produced which later became the Jess Beck Quartet. ARIA award nominations and produced numerous hit singles including Monkey Jess released her debut album Hometown her first number-one single Burn, as well and the Turtle, Party, Wanem Time and the Dress earlier this year. It is a combination as the album’s other top-10 hits, Because beautiful My Island Home, the song that of jazz, folk and Indie pop. Since then, she and Running Back. In 2010 she released was to become her signature tune. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Hop, Skip and Jump: Indigenous Australian Women Performing Within and Against Aboriginalism

JOURNAL OF RESEARCH ONLINE MusicA JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA Hop, Skip and Jump: Indigenous Australian Women Performing Within and Against Aboriginalism Introduction KATELYN BARNEY was in The University of Queensland library talking to one of the librarians, James, about my PhD research. He asked, ‘So, what are you researching again?’ and I replied, ‘Well, I’m working with Indigenous Australian1 women ■ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Iwho perform contemporary music, you know, popular music singers’. James Islander Studies Unit looked confused, ‘Oh, so are you going to interview that guy from the band The University of Queensland 2 Yothu Yindi ?’ This was not the first time I had been asked this and inwardly I Brisbane sighed and replied, ‘No, I’m just focusing my research on Indigenous Australian QLD 4072 women’. Streit-Warburton’s words immediately reverberated in my mind: ‘Ask Australia an Australian to name an Aboriginal singer and there is a fair chance that the answer will be Yothu Yindi’s Mandawuy Yunupingu. Ask again for the name of an Aboriginal woman singer and there is an overwhelming chance that the answer will be Deafening Silence. Deafening Silence is not the name of a singer; it is the pervasive response to most questions about Aboriginal women.’ (1993: 86). As Email: [email protected] I looked at James, I wondered if anything had really changed in more than 10 years. The account above highlights how Indigenous Australian women performers continue to be silenced in discussions and discourses about Indigenous Australian 3 www.jmro.org.au performance. -

SONG for NAIDOC Thursday 7 July 7Pm, Salon Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre

Short Black Opera SONG FOR NAIDOC Thursday 7 July 7pm, Salon Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre ARTISTS ARTISTS Deborah Cheetham AO Edward Bryant Shauntai Batzke Baden Hitchcock Zoy Frangos Sermsah Bin Saad Michael Lapiña John Wayne Parsons Jessica Hitchcock with Toni Lalich, piano Minjaara Atkinson PROGRAM PROGRAM LÉO DELIBES KATE MILLER-HEIDKE, IAIN GRANDAGE & ‘Flower Duet’ from Lakmé LALLY KATZ Deborah Cheetham AO and Shauntai Batzke ‘Flinch’s Dream’ from The Rabbits Jessica Hitchcock BENNY ANDERSSON, BJÖRN ULVAEUS & TIM RICE SIR ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER ‘Anthem’ from Chess ‘Til I Hear You Sing’ from Love Never Dies Zoy Frangos Zoy Frangos GIACOMO PUCCINI DEBORAH CHEETHAM AO ‘Chi il bel sogno’ from La Rondine Excerpts from Pecan Summer: Deborah Cheetham AO ‘In 1964’ ‘Che gelida manina’ from La Boheme Shauntai Batzke & Zoy Frangos Michael Lapina ‘The Meeting Scene’ ‘Si, mi chiamano Mimi’ from La Boheme Short Black Opera Ensemble Shauntai Batzke ‘Biami Creation Story’ ‘O soave fanciulla’ from La Boheme John Wayne Parsons and Jessica Hitchcock Shauntai Batzke and Michael Lapina ‘The Exodus’ FRANCESCO CILEA Short Black Opera Ensemble ‘Io son lumille ancella’ from Adriana Lecouvreur Deborah Cheetham AO ABOUT THE MUSIC Pecan Summer Australia’s first Indigenous opera, written by Deborah Cheetham AO, the opera is based on the events of the 1939 Cummeragunja walk-off. On February 3rd, 1939, hundreds of Yorta Yorta chose to leave their homes on Cummeragunja mission, located on the banks of the Murray River in New South Wales, in protest at harsh conditions and treatment by the mission’s manager. Many opted to start new lives over the border in Victoria. -

Impact Report 2019 Impact Report

2019 Impact Report 2019 Impact Report 1 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report “ Simone Young and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s outstanding interpretation captured its distinctive structure and imaginative folkloric atmosphere. The sumptuous string sonorities, evocative woodwind calls and polished brass chords highlighted the young Mahler’s distinctive orchestral sound-world.” The Australian, December 2019 Mahler’s Das klagende Lied with (L–R) Brett Weymark, Simone Young, Andrew Collis, Steve Davislim, Eleanor Lyons and Michaela Schuster. (Sydney Opera House, December 2019) Photo: Jay Patel Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report Table of Contents 2019 at a Glance 06 Critical Acclaim 08 Chair’s Report 10 CEO’s Report 12 2019 Artistic Highlights 14 The Orchestra 18 Farewelling David Robertson 20 Welcome, Simone Young 22 50 Fanfares 24 Sydney Symphony Orchestra Fellowship 28 Building Audiences for Orchestral Music 30 Serving Our State 34 Acknowledging Your Support 38 Business Performance 40 2019 Annual Fund Donors 42 Sponsor Salute 46 Sydney Symphony Under the Stars. (Parramatta Park, January 2019) Photo: Victor Frankowski 4 5 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report 2019 at a Glance 146 Schools participated in Sydney Symphony Orchestra education programs 33,000 Students and Teachers 19,700 engaged in Sydney Symphony Students 234 Orchestra education programs attended Sydney Symphony $19.5 performances Orchestra concerts 64% in Australia of revenue Million self-generated in box office revenue 3,100 Hours of livestream concerts -

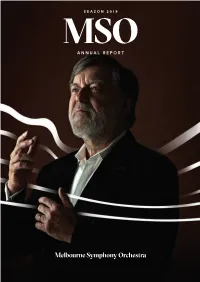

ANNUAL REPORT Contents

SEASON 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Contents Governor's Message 03 Chairman’s Report 04 Managing Director’s Report 0 5 Chief Conductor's Report 06 2019 Highlights 08 Vision, Mission and Values 10 Meet the Orchestra 12 Meet the Chorus 13 2019 Artistic Family 14 Performance Highlights 16 MSO in the Media 20 Contemporary Australia 24 Empowering our Community 30 Celebrating First Nations 36 Reecting our Diversity 40 Discovering the Joy of Music 46 Creative Alliances 50 MSO on the Road 54 Beyond the Concert Hall 58 Our Donors 60 Our Partners 64 Our Management 66 Coporate Governance and Our Board 70 Financial Report 81 Governor’s Message 2019 Annual Report Annual 2019 MESSAGE FOR THE MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra represents the very best of Australian The Melbournemusical Symphonytalent both Orchestrahere and abroadrepresents and, asthe Patron, very bestI am of proud Australian of its musical talent bothachievements here and abroad during and2019., as Patron, I am proud of its achievements during 2019. The Orchestra welcomed a total global audience of more than 5 million The Orchestrapeople welcomedand staged morea total than global 170 performances, audience of includingmore than 20 free5 million concerts. people and A highlight was the celebration of 90 years of free outdoor concerts and Her Excellency, the Honourable Lindastaged Dessau more60 years than in 170 the Sidneyperformances, Myer Music including Bowl: a remarkable20 free concerts. gift to the A peoplehighlight of was the AC, Governor of Victoria and MSO PatroncelebrationVictoria. of 90 years of free outdoor concerts and 60 years in the Sidney Myer Music Bowl: a remarkableThe 2019 year gift also to thesaw peoplethe MSO of tour Victoria to the. -

Media Kit Emma Donovan & the Putbacks

MEDIA KIT EMMA DONOVAN & THE PUTBACKS CHEVRON LIGHTHOUSE SUN 9 FEB TICKETS: $39 Click here for images EMMA DONOVAN AND THE PUTBACKS Acclaimed Indigenous vocalist Emma Donovan and Melbourne rhythm combo The Putbacks burst on to the Australian scene with their album Dawn in 2015, announcing a new voice in Australian soul music. Emma’s songwriting is optimistic, impassioned, and bruisingly honest, The Putbacks’ music is fluid, live and raw, and the collaboration has won friends and admirers all over the world. The project was born of Emma and the band’s shared love for classic US soul and the protest music of Indigenous Australia. Shades of every soul record you ever liked sneak through: Al Green’s Hi Recordsera? Check. Aretha’s Classic Atlantic recordings? Check. Stacks of Stax? Check. It’s all there, but there’s also a whole lot of Coloured Stone and Warumpi Band influences giving this project a uniquely Australian slant. Emma grew up singing church songs with her grandparents on the North coast of New South Wales and her first secular gigs were singing in the family band, The Donovans, with her mother and five uncles. Throughout her career, she has toured and recorded with many of the mainstays of Indigenous music from Archie Roach to Dan Sultan and was a leader of the Black Arm Band project. It was in The Black Arm Band that Emma met members of The Putbacks and their journey together began. The Putbacks are stone cold pros, grizzled veterans of all the tours and all the studios. As individuals, they’re the players behind so many bands it’s difficult to list, but let’s start with Hiatus Kaiyote, The Bombay Royale, D.D Dumbo, Swooping Duck and The Meltdown. -

Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo

melbourne opera Part One of e Ring of the Nibelung WAGNER’S Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Richard Wagner Society (VIC) • Wagner Society (nsw) Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand (RISE) Fund melbourneopera.com Classic bistro wine – ethereal, aromatic, textural, sophisticated and so easy to pair with food. They’re wines with poise and charm. Enjoy with friends over a few plates of tapas. debortoli.com.au /DeBortoliWines melbourne opera WAGNER’S COMPOSER & LIBRETTIST RICHARD WAGNER First performed at Munich National Theatre, Munich, Germany on 22nd September 1869. Wotan BASS Eddie Muliaumaseali’i Alberich BARITONE Simon Meadows Loge TENOR James Egglestone Fricka MEZZO-SOPRANO Sarah Sweeting Freia SOPRANO Lee Abrahmsen Froh TENOR Jason Wasley Donner BASS-BARITONE Darcy Carroll Erda MEZZO-SOPRANO Roxane Hislop Mime TENOR Michael Lapina Fasolt BASS Adrian Tamburini Fafner BASS Steven Gallop Woglinde SOPRANO Rebecca Rashleigh Wellgunde SOPRANO Louise Keast Flosshilde MEZZO-SOPRANO Karen Van Spall Conductors Anthony Negus, David Kram FEB 5, 21 Director Suzanne Chaundy Head of Music Raymond Lawrence Set Design Andrew Bailey Video Designer Tobias Edwards Lighting Designer Rob Sowinski Costume Designer Harriet Oxley Set Build & Construction Manager Greg Carroll German Language Diction Coach Carmen Jakobi Company Manager Robbie McPhee Producer Greg Hocking AM MELBOURNE OPERA ORCHESTRA The performance lasts approximately 2 hours 25 minutes with no interval. Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and The role of Loge, performed by James Egglestone, is proudly supported by Expland (RISE) Fund – an Australian the Richard Wagner Society of Victoria. -

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2019-20

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2019-20 2019-20 03 The Sydney Opera House stands on Tubowgule, Gadigal country. We acknowledge the Gadigal, the traditional custodians of this place, also known as Bennelong Point. First Nations readers are advised that this document may contain the names and images of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are now deceased. Sydney Opera House. Photo by Hamilton Lund. Front Cover: A single ghost light in the Joan Sutherland Theatre during closure (see page 52). Photo by Daniel Boud. Contents 05 About Us Financials & Reporting Who We Are 08 Our History 12 Financial Overview 100 Vision, Mission and Values 14 Financial Statements 104 Year at a Glance 16 Appendix 160 Message from the Chairman 18 Message from the CEO 20 2019-2020: Context 22 Awards 27 Acknowledgements & Contacts The Year’s Our Partners 190 Activity Our Donors 191 Contact Information 204 Trade Marks 206 Experiences 30 Index 208 Performing Arts 33 Precinct Experiences 55 The Building 60 Renewal 61 Operations & Maintenance 63 Security 64 Heritage 65 People 66 Team and Capability 67 Supporters 73 Inspiring Positive Change 76 Reconciliation Action Plan 78 Sustainability 80 Access 81 Business Excellence 82 Organisation Chart 86 Executive Team 87 Corporate Governance 90 Joan Sutherland Theatre foyers during closure. Photo by Daniel Boud. About Us 07 Sydney Opera House. Photo by by Daria Shevtsova. by by Photo Opera House. Sydney About Us 09 Who We Are The Sydney Opera House occupies The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the value of the Opera House’s online presence and programming a unique place in the cultural to our artists and communities, and increased the “It stands by landscape. -

03 List of Members

SENIOR OFFICE BEARERS VISITOR His Excellency The Governor of Victoria, Professor David de Krester, AO MBBS Melb. MD Monash. FRACP FAA FTSE. CHANCELLOR The Hon Justice Alex Chernov, BCom Melb. LLB(Hons) Melb.Appointe d to Council 1 January 1992. Elected DeputyChancello r 8Marc h2004 .Electe dChancello r 10 January2009 . DEPUTY CHANCELLORS Ms Rosa Storelli, Bed Ade CAE GradDipStudWelf Hawthorn MEducStud Monash MACE FACEA AFA1M. Appointed 1 January 2001. Re-appointed 1 January 2005. Elected DeputyChancello r1 January2007 ;re-electe d 1 January2009 . TheHon .Justic eSusa nCrenna n ACB AMel bLL B SydPostGradDi pMelb . Elected June 2009. VICE-CHANCELLOR AND PRINCIPAL Professor Glyn Conrad Davis, AC BA NSWPh DANU .Appointe d 10 January2005 . DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR / PROVOST Professor John Dewar BCL MA Oxon. PhD Griff. Appointed Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Global Relations) 6 April 2009.Appointe d Provost 28 September2009 . DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLORS Professor Peter David Rathjen BSc Hons Adel DPhil Oxon Appointed Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research) 1 May 2008. Professor Susan Leigh Elliott, MB BS Melb. MD Melb. FRACP. Appointed Acting Provost 15 July 2009. Appointed Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Global Engagement) 28 September 2009. Professor Warren Arthur Bebbington, MA Queens (NY) MPhil MMus PhD CUNY. Appointed Pro-Vice-Chancellor (University Relations) 1Januar y 2006. Appointed Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Global Relations) 1Jun e 2008. Appointed Deputy Vice-Chancellor (University Affairs) 28 September 2009. PRO-VICE-CHANCELLORS Professor Geoffrey Wayne Stevens, BE RM1TPh DMelb . FIChemE FAusIMM FTSE CEng. Appointed 1 January2007 . Professor Ron Slocombe, MVSc PhD Mich. ACVP. Appointed 1 January 2009. PRO-VICE-CHANCELLOR (TEACHING AND LEARNING) Philippa Eleanor Pattison, BSc Melb.