New Symbol of Tamil Angst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2011 Deerstalker.P65

THE DEERSTALKER April 2011 THE DEERSTALKER web address: www.newsouthdeerstalkers.org.au NSW Deerstalkers Association COMMITTEE FOR 2011 President: Darren Plumb Formed: 7th June 1972 Ph: 0248447071; 0412021741 Life Members: the late Gordon Alford Bob Penfold Secretary & Wayne McPhee Public Officer: Greg Haywood Jack Boswell 1 Struan Street Paul Wilkes Tahmoor NSW Steve Isaacs 2573 Ph: 02 4681 8363 Affiliated To: Australian Deerstalkers Federation Treasurer: Nalda Haywood Game Management Council (Australia) Inc. Snr. Vice President: John Natoli Contributions: Ph: 04138514336 The editor and editorial committee reserve Jnr. Vice the right to modify any contributions. President: Peter Birchall 26/39-41 Railway St., All contributions are to be mailed or Engadine. emailed to: Club Armourer: John Natoli. Dal Birrell - Editor Game Management 14 Blackall Street Representatives: Greg Haywood, Bulli NSW 2516 Steve Isaacs Mark Isaacs, Greg [email protected] Lee, Peter clark, Les King, Darren Plumb. Advertisements: Licence Testing Advertisements for products sold by Co-ordinator: Greg Haywood NSWDA Members are accepted and printed free of charge provided a discount is given to club members. Video Library: Terry Burgess Cover Photo All Memberships & General Cor- John Desanti with a lovely even Fallow trophy respondence to be posted to: taken early in this year’s season. PO Box 519 PICTON NSW 2571 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Calendar FROM THE EDITOR of This year we will publish five issues of this newsletter. To ensure that we get each Events issue out on time, there will be deadlines for submission of materials to be included. If material reaches me after a deadline, it will be included in the next issue, if appropriate. -

Page 01 March 13.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 22 SPORT | 36 Rajan wants global Uzma reigns rules of conduct supreme at for central banks Doha Golf Club SUNDAY 13 MARCH 2016 • 4 Jumada II 1437 • Volume 21 • Number 6734 thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar Winning leap Emir receives call Al Kuwari slams from Kuwait Emir DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani received last destruction of evening a telephone call from Emir of Kuwait H H Sheikh Sabah Al Ahmad Al Jaber Al Sabah. heritage sites Emir congratulates Mauritius President DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim Emir’s Cultural bin Hamad Al Thani yesterday sent a cable of congratulations to the Advisor says pained President of Mauritius, Ameenah by Homs, Palmyra, Gurib-Fakim, on her country’s Aleppo, Mosul National Day, reports QNA. Dep- uty Emir H H Sheikh Abdullah bin and Nimrod. Hamad Al Thani sent a similar cable to the President of Mauritius. The Peninsula Emir sends message Action from the second leg of the QNB Doha Tour at the Main Arena of the Qatar Equestrian Federation to French President (QEF) in Al Rayyan yesterday. Qatari rider Faleh Suwead Al Ajami guided Armstrong Van De Kapel DOHA: H E Dr Hamad bin Abdulaziz to victory in the second leg while Saudi Arabia’s Abdullah Alsharbatly finished second followed by PARIS: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim Al Kuwari (pictured), Cultural Advi- affects mostly the Middle Eastern Qatar’s Ali Youseff Al Rumaihi. → See also page 29 bin Hamad Al Thani has sent a sor to Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin and Arab regions. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

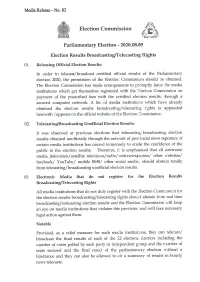

PE 2020 MR 82 S.Pdf

Election Commission – Sri Lanka Parliamentary Election - 05.08.2020 Registered electronic media to disseminate certified election results Last Updated Online Social Media No Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites (FB/ SMS Paper Web Sites) YouTube/ Twitter) 1 Telshan Network TNL TV - - - - - (Pvt) Ltd 2 Smart Network - - - www.lankasri.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 3 Bhasha Lanka (Pvt) - - - www.helakuru.lk - - Ltd 4 Digital Content - - - www.citizen.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 5 Ceylon News - - www.mawbima.lk, - - - Papers (Pvt) Ltd www.ceylontoday.lk Independent ITN, Lakhanda, www.itntv.lk, ITN Sri Lanka 6 Television Network Vasantham TV Vasantham - www.itnnews.lk (FB) - Ltd FM Lakhanda Radio (FB) Sri Lanka City FM 7 Broadcasting - - - - - Corporation (SLBC) Asia Broadcasting Hiru FM. 8 Corparation Hiru TV Shaa FM, www.hirunews.lk, Sooriyan FM, - www.hirugossip.lk - - Sun FM, Gold FM 9 Asset Radio Broadcasting (Pvt) - Neth FM - www.nethnews.lk NethFM(FB) - Ltd 1/4 File Online Number Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites Social Media SMS Paper Web Sites) Asian Media 10 Publications (Pvt) ltd - - www.thinakkural.lk - - - 11 EAP Broadcasting Swarnavahini Shree FM, - www.swarnavahini.lk, - - Company Ran FM www.athavannews.com 12 Voice of Asia Siyatha TV Siyatha FM - - - - Network (Pvt)Ltd Star tamil TV MTV Channel (Pvt) Sirasa TV, Sirasa FM, News 1st (FB), News 1st SMS 13 Ltd / MBC Shakthi TV, Shakthi FM, News 1st (S,T,E), Networks (Pvt) Ltd TV1 Yes FM, - www.newsfirst.lk (Youtube), KIKI mobile YFM, News 1st App Legends FM (Twitter) -

Media Freedom in Post War Sri Lanka and Its Impact on the Reconciliation Process

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford MEDIA FREEDOM IN POST WAR SRI LANKA AND ITS IMPACT ON THE RECONCILIATION PROCESS By Swaminathan Natarajan Trinity Term 2012 Sponsor: BBC Media Action Page 1 of 41 Page 2 of 41 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to thank James Painter, Head of the Journalism Programme and the entire staff of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism for their help and support. I am grateful to BBC New Media Action for sponsoring me, and to its former Programme Officer Tirthankar Bandyopadhyay, for letting me know about this wonderful opportunity and encouraging me all the way. My supervisor Dr Sujit Sivasundaram of Cambridge University provided academic insights which were very valuable for my research paper. I place on record my appreciation to all those who participated in the survey and interviews. I would like to thank my colleagues in the BBC, Chandana Keerthi Bandara, Charles Haviland, Wimalasena Hewage, Saroj Pathirana, Poopalaratnam Seevagan, Ponniah Manickavasagam and my good friend Karunakaran (former Colombo correspondent of the BBC Tamil Service) for their help. Special thanks to my parents and sisters and all my fellow journalist fellows. Finally to Marianne Landzettel (BBC World Service News) for helping me by patiently proof reading and revising this paper. Page 3 of 41 Table of Contents 1 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Challenges to Press Freedom -

The Clan Gillean

Ga-t, $. Mac % r /.'CTJ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/clangilleanwithpOOsinc THE CLAN GILLEAN. From a Photograph by Maull & Fox, a Piccadilly, London. Colonel Sir PITZROY DONALD MACLEAN, Bart, CB. Chief of the Clan. v- THE CLAN GILLEAN BY THE REV. A. MACLEAN SINCLAIR (Ehartottftcton HASZARD AND MOORE 1899 PREFACE. I have to thank Colonel Sir Fitzroy Donald Maclean, Baronet, C. B., Chief of the Clan Gillean, for copies of a large number of useful documents ; Mr. H. A. C. Maclean, London, for copies of valuable papers in the Coll Charter Chest ; and Mr. C. R. Morison, Aintuim, Mr. C. A. McVean, Kilfinichen, Mr. John Johnson, Coll, Mr. James Maclean, Greenock, and others, for collecting- and sending me genea- logical facts. I have also to thank a number of ladies and gentlemen for information about the families to which they themselves belong. I am under special obligations to Professor Magnus Maclean, Glasgow, and Mr. Peter Mac- lean, Secretary of the Maclean Association, for sending me such extracts as I needed from works to which I had no access in this country. It is only fair to state that of all the help I received the most valuable was from them. I am greatly indebted to Mr. John Maclean, Convener of the Finance Committee of the Maclean Association, for labouring faithfully to obtain information for me, and especially for his efforts to get the subscriptions needed to have the book pub- lished. I feel very much obliged to Mr. -

The Conquest of the Great Northwest Piled Criss-Cross Below Higher Than

The Conquest of the Great Northwest festooned by a mist-like moss that hung from tree to tree in loops, with the windfall of untold centuries piled criss-cross below higher than a house. The men grumbled.They had not bargained on this kind of voyaging. Once down on the west side of the Great Divide, there were the Forks.MacKenzie's instincts told him the northbranch looked the better way, but the old guide had said only the south branch would lead to the Great River beyond the mountains, and they turned up Parsnip River through a marsh of beaver meadows, which MacKenzie noted for future trade. It was now the 3rd of June.MacKenzie ascended a. mountain to look along the forward path. When he came down with McKay and the Indian Cancre, no canoe was to be found.MacKenzie sent broken branches drifting down stream as a signal and fired gunshot after gunshot, but no answer!Had the men deserted with boat and provisions?Genuinely alarmed, MacKenzie ordered McKay and Cancre back down the Parsnip, while he went on up stream. Whichever found the canoe was to fire a gun.For a day without food and in drenching rains, the three tore through the underbrush shouting, seeking, despairing till strength vas ethausted and moccasins worn to tattersBarefoot and soaked, MacKenzie was just lying down for the night when a crashing 64 "The Coming of the Pedlars" echo told him McKay had found the deserters. They had waited till he had disappeared up the mountain, then headed the canoe north and drifted down stream. -

Download (8MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Working Together for Prevention and Control of Zoonoses in India Syed Shahid Abbas submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex September 2018 2 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis, whether in the same or different form, has not been previously submitted to this or any other University for a degree. 3 For Ammar & Zahra 4 University of Sussex Syed Shahid Abbas Doctor of Philosophy Working Together for Prevention and Control of Zoonoses in India Summary Despite calls for collaborations across animal and human health sectors to control zoonoses, a ‘black-box’ approach to collaborations means there is limited understanding of their drivers, characteristics and dynamics. In this thesis, I develop insights into multisector ‘One Health’ collaborations by examining the case of three zoonotic diseases in two states in India. Over nine months of fieldwork, I interviewed policy actors spread across different sectors, functions and administrative levels, and observed the practices of professionals in the field and in their offices. -

Communicating Coastal and Marine Biodiversity

Training Resource Material Coastal and Marine Biodiversity and Protected Area Management Module 11 Communicating coastal and marine biodiversity For MPA Managers Photo by: Sarang Kulkarni 2 Training Resource Material Coastal and Marine Biodiversity and Protected Area Management Module 11 Communicating coastal and marine biodiversity For MPA Managers Summary This module will help the MPA managers understand how media looks at coastal and marine conservation issues. Since conservation is not a media priority topic and MPAs come into news only when an accident happens, the module will help managers to gain knowledge and skills for effectively engaging media on conservation issues. The module will introduce different tools for media relations, explaining their strengths and limitations. It will also discuss how to use these tools during a crisis communication situation. 3 Imprint Training Resource Material: Coastal and Marine Biodiversity and Protected Area Management for MPA Managers Module 1: An Introduction to Coastal and Marine Biodiversity Module 2: Coastal and marine Ecosystem Services and their Value Module 3: From Landscape to seascape Module 4: Assessment and monitoring of coastal and marine biodiversity and relevant issues Module 5: Sustainable Fisheries Management Module 6: Marine and Coastal Protected Areas Module 7: Governance, law and policies for managing coastal and marine ecosystems, biodiversity and protected areas Module 8: Coasts, climate change, natural disasters and coastal livelihoods Module 9: Tools for mainstreaming: impact assessment and spatial planning Module 10: Change Management and connectedness to nature Module 11: Communicating Coastal and Marine Biodiversity Conservation issues Module 12: Effective management Planning of coastal and marine protected areas ISBN 978-81-933282-5-5 December 2016 Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Wildlife Institute of India (WII) Indira Gandhi National Forest Academy Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH P.O. -

Dan-Brockington-Celebrity-And-The

More praise for Celebrity and the Environment ‘More exposé than a tabloid. More weight than a broadsheet ... Brockington lends academic muscle to what, I suspect, many of us instinctively feel about these issues. Extensively researched yet winsomely written and, thankfully, not veering into cynicism which a book on this subject could easily do. Enlightening and easily accessible by the armchair environmentalist.’ Terry Clark, St Luke’s Church, Glossop ‘I was surprised by this book. Anything containing the mere word “celebrity” will normally see me heading for the hills at speed, let alone a whole book on the subject! Dan’s book is written with wit and grace. His research was clearly meticulous and the result is a book that is informative and enjoyable.’ Robin Barker, Countrycare Children’s Homes ‘In an analysis that builds on a large literature examining interlinkages between conservation and corporate interest, Dan Brockington turns a new corner, investigating how the rich and famous lend their glamour to the noble goal of saving the planet. In reality conservation is a highly political pursuit with winners and losers. Brockington provides a well- balanced account of the pros of harnessing the razzamatazz of celebrity to the conservation cause with the cons of sanitizing the harsh realities of conservation politics and the insidious danger of commoditizing nature. If you want to embark on the journey in to contemporary conservation you would go well with this book.’ Monique Borgerhoff Mulder and Tim Caro, University of California at Davis ‘A thoroughly stimulating book that made me question my role as a conservation filmmaker.’ Jeremy Bristow, director and writer About the author Dan Brockington has a PhD in anthro- pology from UCL and is happiest conducting long-term research in remote rural areas. -

PE 2020 MR 82 E.Pdf

Election Commission – Sri Lanka Parliamentary Election - 05.08.2020 Registered electronic media to disseminate certified election results Last Updated Online Social Media No Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites (FB/ SMS Paper Web Sites) YouTube/ Twitter) 1 Telshan Network TNL TV - - - - - (Pvt) Ltd 2 Smart Network - - - www.lankasri.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 3 Bhasha Lanka (Pvt) - - - www.helakuru.lk - - Ltd 4 Digital Content - - - www.citizen.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 5 Ceylon News - - www.mawbima.lk, - - - Papers (Pvt) Ltd www.ceylontoday.lk Independent ITN, Lakhanda, www.itntv.lk, ITN Sri Lanka 6 Television Network Vasantham TV Vasantham - www.itnnews.lk (FB) - Ltd FM Lakhanda Radio (FB) Sri Lanka City FM 7 Broadcasting - - - - - Corporation (SLBC) Asia Broadcasting Hiru FM. 8 Corparation Hiru TV Shaa FM, www.hirunews.lk, Sooriyan FM, - www.hirugossip.lk - - Sun FM, Gold FM 9 Asset Radio Broadcasting (Pvt) - Neth FM - www.nethnews.lk NethFM(FB) - Ltd 1/4 File Online Number Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites Social Media SMS Paper Web Sites) Asian Media 10 Publications (Pvt) ltd - - www.thinakkural.lk - - - 11 EAP Broadcasting Swarnavahini Shree FM, - www.swarnavahini.lk, - - Company Ran FM www.athavannews.com 12 Voice of Asia Siyatha TV Siyatha FM - - - - Network (Pvt)Ltd Star tamil TV MTV Channel (Pvt) Sirasa TV, Sirasa FM, News 1st (FB), News 1st SMS 13 Ltd / MBC Shakthi TV, Shakthi FM, News 1st (S,T,E), Networks (Pvt) Ltd TV1 Yes FM, - www.newsfirst.lk (Youtube), KIKI mobile YFM, News 1st App Legends FM (Twitter) -

The Case of Tamil Nadu

CINEMATIC CHARISMA AS A POLITICAL GATEWAY IN SOUTH INDIA: THE CASE OF TAMIL NADU Dhamu Pongiyannan, MA Submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at The University of Adelaide 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... i List of Figures .................................................................................................................. iv Abstract............. ............................................................................................................... vi Declaration. ..................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ viii Dedication....... ............................................................................................................... viii Situating Tamil Nadu in the Subcontinent ........................................................................ x Preface................ ............................................................................................................. xi Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Ordinary Tamils, extraordinary celebrity devotion .................................................