Introduction: the Problem of Cavendish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cavendish Weighs the Earth, 1797

CAVENDISH WEIGHS THE EARTH Newton's law of gravitation tells us that any two bodies attract each other{not just the Earth and an apple, or the Earth and the Moon, but also two apples! We don't feel the attraction between two apples if we hold one in each hand, as we do the attraction of two magnets, but according to Newton's law, the two apples should attract each other. If that is really true, it might perhaps be possible to directly observe the force of attraction between two objects in a laboratory. The \great moment" when that was done came on August 5, 1797, in a garden shed in suburban London. The experimenter was Lord Henry Cavendish. Cavendish had inherited a fortune, and was therefore free to follow his inclinations, which turned out to be scientific. In addition to the famous experiment described here, he was also the discoverer of “inflammable air", now known as hydrogen. In those days, science in England was often pursued by private citizens of means, who communicated through the Royal Society. Although Cavendish studied at Cambridge for three years, the universities were not yet centers of scientific research. Let us turn now to a calculation. How much should the force of gravity between two apples actually amount to? Since the attraction between two objects is proportional to the product of their masses, the attraction between the apples should be the weight of an apple times the ratio of the mass of an apple to the mass of the Earth. The weight of an apple is, according to Newton, the force of attraction between the apple and the Earth: GMm W = R2 where G is the \gravitational constant", M the mass of the Earth, m the mass of an apple, and R the radius of the Earth. -

Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in: Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa40899 _____________________________________________________________ Paper: Tucker, J. Richard Price and the History of Science. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 23, 69- 86. _____________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ 69 RICHARD PRICE AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE John V. Tucker Abstract Richard Price (1723–1791) was born in south Wales and practised as a minister of religion in London. He was also a keen scientist who wrote extensively about mathematics, astronomy, and electricity, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in support of a national history of science for Wales, this article explores the legacy of Richard Price and his considerable contribution to science and the intellectual history of Wales. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Henry Cavendish Outline

Ann Karimbabai Massihi Sveti Patel Sandy Saekoh Thomas Choe Chemistry 480 Dr. Harold Goldwhite Henry Cavendish I. Childhood A. Henry Cavendish was born in Nice, France, on 10 October1731, and died alone on 24 February 1810. B. His parental grandfather was Duke of Devonshire and his maternal grandfather was Duke of Kent 1 C. His parents were English aristocrats. D. His father was Lord Charles Cavendish, a member of Royal Society in London and an experimental scientist. E. His father made his own scientific equipment for him. II. Education A. At age of 11, he attended Dr. Newcome’s Academy in Hackney, London from 1749-1753. B. In 1749, he went to Peterhouse College. C. He left the college at 1753 without a degree. D. His father encouraged his scientific interest and introduced him to the Royal Society and he became a member in 1760. III. Papers A. Since he did his scientific investigation for his pleasure, he was careless in publishing the results. B. In 1776, he published his 1st paper about the existence of hydrogen as a substance. 1. He received the Copley Medal of the Royal Society for this achievement. C. In 1771, a theoretical study of electricity. D. In 1784, the synthesis of water. E. In 1798, the determination of the gravitational constant. IV. Experiments A. Fixed air (CO2) produced by mixing acids and bases. B. “Inflammable air” (hydrogen) generated by the action of acid on metals. 2 Figure 1. Cavendish's apparatus for making and collecting hydrogen Gas bladder used by Henry Cavendish 3 C. -

Section 1 – Oxygen: the Gas That Changed Everything

MYSTERY OF MATTER: SEARCH FOR THE ELEMENTS 1. Oxygen: The Gas that Changed Everything CHAPTER 1: What is the World Made Of? Alignment with the NRC’s National Science Education Standards B: Physical Science Structure and Properties of Matter: An element is composed of a single type of atom. G: History and Nature of Science Nature of Scientific Knowledge Because all scientific ideas depend on experimental and observational confirmation, all scientific knowledge is, in principle, subject to change as new evidence becomes available. … In situations where information is still fragmentary, it is normal for scientific ideas to be incomplete, but this is also where the opportunity for making advances may be greatest. Alignment with the Next Generation Science Standards Science and Engineering Practices 1. Asking Questions and Defining Problems Ask questions that arise from examining models or a theory, to clarify and/or seek additional information and relationships. Re-enactment: In a dank alchemist's laboratory, a white-bearded man works amidst a clutter of Notes from the Field: vessels, bellows and furnaces. I used this section of the program to introduce my students to the concept of atoms. It’s a NARR: One night in 1669, a German alchemist named Hennig Brandt was searching, as he did more concrete way to get into the atomic every night, for a way to make gold. theory. Brandt lifts a flask of yellow liquid and inspects it. Notes from the Field: Humor is a great way to engage my students. NARR: For some time, Brandt had focused his research on urine. He was certain the Even though they might find a scientist "golden stream" held the key. -

The Conservatives in British Government and the Search for a Social Policy 1918-1923

71-22,488 HOGAN, Neil William, 1936- THE CONSERVATIVES IN BRITISH GOVERNMENT AND THE SEARCH FOR A SOCIAL POLICY 1918-1923. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 History, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE CONSERVATIVES IN BRITISH GOVERNMENT AND THE SEARCH FOR A SOCIAL POLICY 1918-1923 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Neil William Hogan, B.S.S., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by I AdvAdviser iser Department of History PREFACE I would like to acknowledge my thanks to Mr. Geoffrey D.M. Block, M.B.E. and Mrs. Critch of the Conservative Research Centre for the use of Conservative Party material; A.J.P. Taylor of the Beaverbrook Library for his encouragement and helpful suggestions and his efficient and courteous librarian, Mr. Iago. In addition, I wish to thank the staffs of the British Museum, Public Record Office, West Sussex Record Office, and the University of Birmingham Library for their aid. To my adviser, Professor Phillip P. Poirier, a special acknowledgement#for his suggestions and criticisms were always useful and wise. I also want to thank my mother who helped in the typing and most of all my wife, Janet, who typed and proofread the paper and gave so much encouragement in the whole project. VITA July 27, 1936 . Bom, Cleveland, Ohio 1958 .......... B.S.S., John Carroll University Cleveland, Ohio 1959 - 1965 .... U. -

Modern Outlook on the Concept of Temperature Edward Bormashenko Chemical Engineering Department, Engineering Faculty, Ariel University, P.O.B

What Is the Temperature? Modern Outlook on the Concept of Temperature Edward Bormashenko Chemical Engineering Department, Engineering Faculty, Ariel University, P.O.B. 3, 407000 Ariel, Israel ORCID id 0000-0003-1356-2486 Abstract The meaning and evolution of the notion of “temperature” (which is a key concept for the condensed and gaseous matter theories) is addressed from the different points of view. The concept of temperature turns out to be much more fundamental than it is conventionally thought. In particular, the temperature may be introduced for the systems built of “small” number of particles and particles in rest. The Kelvin temperature scale may be introduced into the quantum and relativistic physics due to the fact, that the efficiency of the quantum and relativistic Carnot cycles coincides with that of the classical one. The relation of the temperature to the metrics of the configurational space describing the behavior of system built from non-interacting particles is demonstrated. The Landauer principle asserts that the temperature of the system is the only physical value defining the energy cost of isothermal erasing of the single bit of information. The role of the temperature the cosmic microwave background in the modern cosmology is discussed. Keywords: temperature; quantum Carnot engine; relativistic Carnot cycle; metrics of the configurational space; Landauer principle. 1. Introduction What is the temperature? Intuitively the notions of “cold” and “hot” precede the scientific terms “heat” and “temperature”. Titus Lucretius Carus noted in De rerum natura that “warmth” and “cold” are invisible and this makes these concepts difficult for understanding [1]. The scientific study of heat started with the invention of thermometer [2]. -

Phyzguide: Weighing the Earth

PhyzGuide: Weighing the Earth IN SEARCH OF “G” In 1665, 22 year-old Isaac Newton derived the law of universal gravitation. This law can be summarized by the equation that describes the gravitational force of attraction between any two masses. F = G Mm R2 Although Newton was able to verify the validity of the “inverse-square” nature of this formula through calculations involving the orbit of the moon, he was never able to determine the value of the constant G (the universal gravitation constant). The equation could only be used as the proportion F∝Mm/R2 until the value of G was determined. The problem in determining G was that in order to do so, you needed to know the gravitational force between two known masses separated by a known distance: 2 G = FR Mm One could easily determine the attraction between an object of known mass and the Earth by weighing it, but the mass of the Earth was not known during Newton’s lifetime. Before the end of the eighteenth century, however, the answer would be found! The Book of Phyz © Dean Baird. All rights reserved. 9/17/14 db THE CAVENDISH EXPERIMENT In 1798, Henry Cavendish devised an experiment to determine the value of G. Instead of involving the gravitational force exerted by the Earth, he measured the gravitational attraction between two known masses in his lab. Measuring this force was difficult because it was exceedingly small (about 10–9 N or 0.000 000 001 N). Cavendish was able to accurately measure this force by using a highly delicate torsion balance as shown below. -

Argon out of Thin Air Markku Räsänen Remembers Making a Neutral Compound Featuring Argon, and Ponders on the Reactivity of This Inert Element

in your element Argon out of thin air Markku Räsänen remembers making a neutral compound featuring argon, and ponders on the reactivity of this inert element. he discovery of the noble gases shows improper handling of the reactive precursor how innovative researchers have HF, the first signals of this new species were Tbeen when it came to separating and obtained in my group on 21 December identifying minor amounts of components 1999 — a time of the year conducive to from mixtures using relatively simple tools. experimentation, with no interfering students First indications of an inert component present in the lab. Conclusive experimental in air appeared in 1785 through results were obtained from the vibrational Henry Cavendish’s experimental studies, spectral effects of H/D and36 Ar/40Ar isotopic when he found about 1% of an unreactive substitutions3. A neutral molecule containing component. He could not, however, identify argon — I couldn’t have wished for a better the unreactive species, which turned out to Christmas present. be argon, and the names connected with its A number of stable argon compounds discovery are Lord Rayleigh and Sir William have been computationally predicted, and Ramsay (pictured). In 1892, Rayleigh and are waiting for experimental verification. Ramsay’s exceptionally skilful eudiometric Recent extensions of this chemistry measurements, after chemical separation of include, for example, the preparation and the constituents, revealed that the density / ALAMY © THE PRINT COLLECTOR characterization of ArBeS (ref. 4) and ArAuF of nitrogen prepared by removing oxygen, (ref. 5). Our chemical understanding of the carbon dioxide and water from air with chemically. -

Volta and the Quantitative Conceptualisation of Electricity: from Electrical Capacity to the Preconception of Ohm’S Law1

Jürgen Teichmann Volta and the Quantitative Conceptualisation of Electricity: From Electrical Capacity to the Preconception of Ohm’s Law1 The development of electric measurement technology in the eighteenth century laid the basis for establishing electricity as a new – and in a certain way quasi- technological – branch of physics. Very important in this context are the role of the frictional electrical machine from the forties onwards, the invention of the Leyden jar in 1746 and the development of lightning rod electrotechnology, from 1751, in connection with atmospheric electricity. Electricity was also useful for medical purposes. But this was not so important for the research of those scientists who were mainly interested in physics (“physique particulière”, in the sense of the famous French Encyclopédie). The development of an independent instrumental and conceptual electrical cosmos showed that electricity required an important place within the expanding experimental physics of the eighteenth century – ranking at least with “aerometry”, “thermometry” and “meteorology”. At the same time electrotechnology (lightning rods) met with more response in public than any technical consequence of the other branches of science. I will show that Volta’s conceptual development itself, with his instruments and measuring methods, defined what science should be, what experimental and theoretical steps should be taken first and how one should talk about all that. I will also show how difficult it was to combine these developments with the existing complicated models of mechanics. They often stayed separated. Here action at-a- distance and fluid action were not decisive opposites. No common language was used in electricity, no broad communication – e.g. -

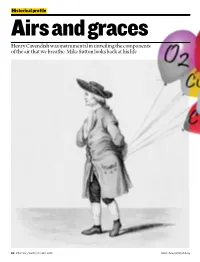

Henry Cavendish Was Instrumental in Unveiling the Components of the Air That We Breathe

Historical profile Airs and graces Henry Cavendish was instrumental in unveiling the components of the air that we breathe. Mike Sutton looks back at his life 50 | Chemistry World | October 2010 www.chemistryworld.org mathematics at the University of or tin released the same quantity In short Cambridge (without taking a degree) of the gas, regardless of whether before joining London’s scientific Henry Cavendish’s they were dissolved in spirit of salt community. He became a fellow of meticulous lab (hydrochloric acid) or dilute oil of the Royal Society in 1760 and was work helped to open vitriol (sulfuric acid). elected to its council in scientists’ eyes to the So Cavendish reached the 1765. existence and properties reasonable (but erroneous) Cavendish of hydrogen, carbon conclusion that inflammable air was took an active dioxide and nitrogen a constituent of zinc, iron and tin interest in He proved that the dew and liberated by acids. He seems to mathematics, formed when hydrogen have suspected that the ‘air’ might astronomy, was exploded with actually be pure phlogiston, the fiery meteorology oxygen was water matter which early modern chemists and physics. He also isolated argon, like Ernst Stahl (1660–1734) But his first which then remained believed to exist in all combustible scientific unidentified for over substances. However, he also publication, 100 years considered the possibility that it was which appeared He had an obsessive a more complex substance in which in three parts eye for detail and often phlogiston played some part. in Philosophical considered his work Part two of Cavendish’s paper Transactions in 1766 unworthy of publication concerned fixed air (carbon (and earned him the Royal dioxide). -

Richard Price and the History of Science

69 RICHARD PRICE AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE John V. Tucker Abstract Richard Price (1723–1791) was born in south Wales and practised as a minister of religion in London. He was also a keen scientist who wrote extensively about mathematics, astronomy, and electricity, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in support of a national history of science for Wales, this article explores the legacy of Richard Price and his considerable contribution to science and the intellectual history of Wales. The article argues that Price’s real contribution to science was in the field of probability theory and actuarial calculations. Introduction Richard Price was born in Llangeinor, near Bridgend, in 1723. His life was that of a Dissenting Minister in Newington Green, London. He died in 1791. He is well remembered for his writings on politics and the affairs of his day – such as the American and French Revolutions. Liberal, republican, and deeply engaged with ideas and intellectuals, he is a major thinker of the eighteenth century. He is certainly pre-eminent in Welsh intellectual history. Richard Price was also deeply engaged with science. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society for good reasons. He wrote about mathematics, astronomy and electricity. He had scientific equipment at home. He was consulted on scientific questions. He was a central figure in an eighteenth-century network of scientific people. He developed the mathematics and data needed to place pensions and insurance on a sound foundation – a contribution to applied mathematics that has led to huge computational, financial and social progress.