FIELD, Issue 42, Spring 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping as usual that you are all safe and well in these troubled times. Our cinema doors are still well and truly open, I’m pleased to say, the channel has been transmitting 24 hours a day 7 days a week on air with a number of premières for you all and orders have been posted out to you all every day as normal. It’s looking like a difficult few months ahead with lack of advertising on the channel, as you all know it’s the adverts that help us pay for the channel to be transmitted to you all for free and without them it’s very difficult. But we are confident we can get over the next few months. All we ask is that you keep on spreading the word about the channel in any way you can. Our audiences are strong with 4 million viewers per week , but it’s spreading the word that’s going to help us get over this. Can you believe it Talking Pictures TV is FIVE Years Old later this month?! There’s some very interesting selections in this months newsletter. Firstly, a terrific deal on The Humphrey Jennings Collections – one of Britain’s greatest filmmakers. I know lots of you have enjoyed the shorts from the Imperial War Museum archive that we have brought to Talking Pictures and a selection of these can be found on these DVD collections. -

My Commonplace Book

QJarnell Unioeroitg ffiihtarg BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 Cornell University Library PN 6081.H12 3 1924 027 665 524 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924027665524 MY COMMONPLACE BOOK MY COMMONPLACE BOOK T. HACKETT J. ^ " ' Omne meum, nihil meum T. FISHER UNWIN LTD LONDON : ADELPHI TERRACE n First publication in Great Britain .... 1919- memories ! O past that is ! George EuoT DEDICATED TO MY DEAR FRIEND RICHARD HODGSON WHO HAS PASSED OVER TO THE OTHER SIDE Of wounds and sore defeat I made my battle-stay ; Winged sandals for my feet I wove of my delay ; Of weariness and fear I made my shouting spear ; Of loss, and doubt, and dread, And swift oncoming doom I made a helmet for my head And a floating plume. From the shutting mist of death, From the failure of the breath I made a battle-horn to blow Across the vales of overthrow. O hearken, love, the battle-horn I The triumph clear, the silver scorn I O hearken where the echoes bring, Down the grey disastrous morn. * Laughter and rallying ! Wn^uAM Vaughan Moody. From Richard Hodgson's Christmas Card, 1904, the Christmu before bis death I cannot but remember such things were. That were most precious to me. Macbeth, IV, 3. PREFACE* A I/ARGE proportion of the most interesting quotations in this book was collected between 1874 and 1886. -

Dear Volunteer Applicant, We Want You to Be Familiar with the Attached

Dear volunteer applicant, We want you to be familiar with the attached readings as part of your volunteer application process. Studying these readings will contribute to your awareness of jail operations, your awareness of your own behavior while in the jail, and overall jail security. Knowing what is in these readings will add to your personal safety while you are in the jail. Please read these selections, complete and sign the last (signature) page, and return the last page to the Chaplains Office. Do not hesitate to ask us if you have questions about the readings. Thank you for your interest in serving as a volunteer at the Benton County Jail! Sincerely, Beki Hissam, Chaplain Matthew Kuempel, Chaplain Dee Willis, Chaplain Chaplains Office Benton County Jail 7122 W. Okanogan Pl., Bldg. B Kennewick, WA 99336 email: [email protected] Benton County Sheriff‘s Office Bureau of Corrections Inmate Handbook Revised 2009 The purpose of this handbook is to provide incoming inmates with general information regarding the Bureau of Corrections Programs rules and regulations inmates will encounter during confinement. The intent of this handbook is to help new inmates understand their responsibilities when they enter jail and assist them in their adjustment while in this facility. BENTON COUNTY JAIL 7122 West Okanogan Building B Kennewick, WA 99336 ii BEHAVIOR The best control of behavior is self-discipline. Failure to comply with rules may be cause for disciplinary action or further criminal prosecution. Corrections staff may also REVOKE YOUR PRIVILEGES on a temporary basis for breaking the rules or other misconduct. Always conduct yourself in a respectful manner. -

The Rules of Life, Second Edition, by Richard Templar, Published by Pearson Education Limited, ©Pearson Education 2010

THE RULES OF LIFE A personal code for living a better, happier, and more successful kind of life Expanded Edition RICHARD TEMPLAR Vice President, Publisher: Tim Moore Associate Publisher and Director of Marketing: Amy Neidlinger Operations Manager: Gina Kanouse Senior Marketing Manager: Julie Phifer Publicity Manager: Laura Czaja Assistant Marketing Manager: Megan Colvin Cover Designer: Sandra Schroeder Managing Editor: Kristy Hart Senior Project Editor: Lori Lyons Proofreader: Gill Editorial Services Senior Compositor: Gloria Schurick Manufacturing Buyer: Dan Uhrig ©2011 by Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as FT Press Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458 Authorized adaptation from the original UK edition, entitled The Rules of Life, Second Edition, by Richard Templar, published by Pearson Education Limited, ©Pearson Education 2010. This U.S. adaptation is published by Pearson Education Inc, ©2010 by arrangement with Pearson Education Ltd, United Kingdom. FT Press offers excellent discounts on this book when ordered in quantity for bulk purchases or special sales. For more information, please contact U.S. Corporate and Government Sales, 1-800-382-3419, [email protected]. For sales outside the U.S., please contact International Sales at [email protected]. Company and product names mentioned herein are the trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Rights are restricted to U.S., its dependencies, and the Philippines. Printed in the United States of America First Printing November 2010 ISBN-10: 0-13-248556-7 ISBN-13: 978-0-13-248556-2 Pearson Education LTD. -

James Whitcomb Riley - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Whitcomb Riley - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Whitcomb Riley(7 October 1849 - 22 July 1916) James Whitcomb Riley was an American writer, poet, and best selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the Hoosier Poet and Children's Poet for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man". Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and was involved in a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy. Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. -

SENATE-Monday, March 3, 1986

March 3, 1986 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 3389 SENATE-Monday, March 3, 1986 <Legislative day of Monday, February 24, 1986) The Senate met at 12 noon, on the business will not extend beyond the lower dollar would slow the growth of expiration of the recess, and was hour of 1:30 p.m., with Senators per imports. We were told that actions called to order by the President pro mitted to speak therein for not more had been taken to prevent foreign tex tempore [Mr. THURMOND]. than 5 minutes each. tile products from flooding our mar The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Following routine morning business, kets. Unfortunately, this is not the prayer today will be offered by the the Senate may return to the techni case. Reverend Monsignor John Murphy, cal corrections package to the farm For 2 months in a row, textile im St. Joseph's Church, Washington, DC. bill, or the committee funding resolu ports have increased by over 40 per tion, or possibly the balanced budget PRAYER cent. From September 1985 through amendment. January 1986, imports of textiles were The Reverend Monsignor John The Senate may also turn to the up over 31 percent. The year 1985 Murphy, St. Joseph's Church, Wash consideration of any legislative or ex marked the fifth consecutive year that ington, DC, offered the following ecutive items which have been previ textile and apparel imports have prayer: ously cleared for action. Rollcall votes Heavenly Father, Who art in could occur during the session today. reached new record levels. No wonder Heaven, praised be Your name. -

All-Out for Victor Y!

jOHN From the reviews of A LIVELY LOOK AT MAGAZINE ADS uplifting the morale of civilians and GIs, and ads BUSH THE SONGS THAT FOUGHT THE WAR: jONES DURING WORLD WAR II AND THEIR promoting home front efficiency, conservation, POPULAR MUSIC AND THE HOME FRONT, ROLES IN SUSTAINING MORALE AND and volunteerism. Jones also includes ads MAGAZINE ADVERTISING AND THE WORLD WAR II HOME FRONT WAR AND THE WORLD ADVERTISING MAGAZINE ALL-OUT FOR VICTORY! 1939–1945 PROMOTING HOME-FRONT SUPPORT praising women in war work and the armed OF THE WAR, WITH LOTS OF forces and ads aimed at recruiting more women. “The Songs That Fought the War serves as a way to comprehend the ILLUSTRATIONS Taken together, war ads in national magazines immensity and impact of World War II on the American people . did their part to create the most efficient home The result is a comprehensive thematic overview of the mindset Following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the front possible in order to support the war of the American people and how writers of popular music tried to entry of the United States into World War II, effort. document the collective understanding of their generation.” many commercial advertisers and their Madison — Indiana Magazine of History Avenue ad agencies instantly switched from selling products and services to selling the home “Scholars have too often ignored [popular songs], which reveal the front on ways to support the war. Ads by major moods, the yearnings, the memories of the ordinary people. John manufacturers showcased how their factories Bush Jones’s book is a valuable and even charming corrective to had turned to war production, demonstrating this scholarly neglect.”— Vingtième Siècle their participation in the war and helping people understand, for instance, that they couldn’t buy “Mr. -

Idiom Dictionary

2009 Idiom Dictionary Laura Jeffcoat Languagelab.com 1/11/2009 Table of Contents ~ A ~ ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 ~ B ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 13 ~ C ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 30 ~ D ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 43 ~ E ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 53 ~ F ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 57 ~ G ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 65 ~ H ~ .................................................................................................................................................... 75 ~ I ~ ..................................................................................................................................................... 85 ~ J ~.................................................................................................................................................... -

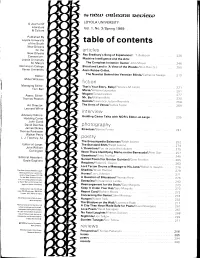

Table of Contents New Orleans for the Articles New Orleans Ray Bradbury's Song of Experience/L T

the necv ORleans Revierv A Journal Of LOYOLA UNIVERSITY Literature Vol. 1. No. 3/Spring 1969 & Culture Published By Loyola University of the South table of contents New Orleans for the articles New Orleans Ray Bradbury's Song of Experience/L T. B1dd1son Consortium: 226 Loyola University Machine Intelligence and the Arts: St. Mary's The Compleat Imitation Game/ John Mosier 246 Dominican College Blood and Land in 'A View of the Woods'/Don R1so. S.J 255 Xavier University Alain Robbe-Grillet, The Novelist Behind the Venetian Blinds/Catherine Savage Editor: 213 Miller Williams fiction Managing Editor: That's Your Story, Baby/Florence M Hecht .............. 221 Tom Bell Marie/William Kotzwinkle .................. 251 Mogen/Gerald Locklin . ........ Assoc. Editor: 277 Thomas Preston Mr. Bo/Will1am Mills . ...... 230 Secrets/Lawrence Judson Reynolds . 259 Art Director: The Arms of Venus/James Tipton 264 Leonard White interview Advisory Editors: Hodding Carter Talks with NOR's Editor-at-Large Hodding Carter 235 John Ciardi David Daiches photography James Dickey Streetcar/Barney Fortier ............... 241 Thomas Parkinson Walker Percy L. J. Twomey, SJ poetry The Encyclopedia Salesman/Ralph Adamo ................ 252 Editor-at-Large: The Standard Shift/Ralph Adamo . ............ 274 John William L'Ouverture/Fort de Joux/Aiv1n Aubert ..................... 275 Corrington Were There Identifying Marks on the Barracuda?/Ann Darr 257 Elsewhere/Gene Frumkin.. ......... Editorial Assistant: 245 Gayle Gagliano Sunset Poem (for Gordon Quinlan)/Gene Frumk1n 265 Requiem/RobertS Gwynn ..................... 263 Lord Tarzan Drums a Message to His Jane/RobertS. Gwynn 276 The New Orleans Review is pub Shedlitz/Shael Herman . ...... 279 lished quarterly by Loyola Uni versity, New Orleans (70118) Honey/Larry Johnson . -

PRO 050620 A1 CMYK.Indd

Anahuac National Bank 801 South Ross Sterling (409) 267-3106 • www.anbank.net A Family of Community Banks East Chambers County Bank Winnie, TX 77665 (409) 296-2265 • www.eastccbank.net Serving Southeast Texas Barbers Hill Bank Eagle Drive & (Inside HEB) Independently Owned and Operated with Locations Mont Belvieu, TX 77580 across Chambers and Liberty County! (281) 385-6455 • www.bhbank.net Hardin Bank Hardin, TX 77561 (936) 298-2265 • www.hardinbank.net TThehe PPrroogressgress SServingerving CChambershambers CCountyounty SSinceince 11908908 WWednesdayednesday • MMayay 66,, 22020020 • wwww.theanahuacprogress.comww.theanahuacprogress.com • VVolumeolume 111111 - NNo.o. 4411 • 775¢5¢ Obituary Notices Deputies arrest two men after attempting to Raul Bosquez buy a trailer with a stolen credit card Mae Hillyer heriff Brian Hawthorne with a stolen credit card. Upon for the warrant, the deputy Wayne King reports that on arrival, contact was made with the approached a second suspect, later Alva Standley Wednesday April 29, suspect who was identified as identified as 27-year old Michael DETAILS ON PAGE 4A 2020 at approximately 25-year old Myles Curtis Akins of Anthony Barrientos, of San Antonio, 4:00 p.m., a Chambers Austin, Texas. A check with Texas, who was the driver of a CountyS deputy was dispatched to Dispatch revealed that Akins had an Dodge Ram 1500 four door truck INSIDE Extreme Trailers of Texas located outstanding felony theft warrant out waiting in the parking lot to pick up at 15625 IH-10 in reference to a of Bexar County. Myles Michael Around Town 2A male trying to purchase a trailer After placing Akins into custody ARRESTS-3A Barrientos Obituary notices 4A Akins Local News 5A Business Directrory 8A Classifi eds 8A Miss Evelyn turns 98 New Submitted by Jan. -

In the Loop: a Reference Guide to American English Idioms

IN THE LOOP A Reference Guide to American English Idioms In the Loop: A Reference Guide to American English Idioms Published by the Office of English Language Programs United States Department of State Washington, DC 20037 First Edition 2010 Adapted from: Something to Crow About by Shelley Vance Laflin; ed. Anna Maria Malkoç, Frank Smolinski Illustrated American Idioms by Dean Curry Special thanks to Elizabeth Ball for copyediting and proofreading this 2010 edition. Office of English Language Programs Bureau of Cultural and Educational Affairs United States Department of State Washington, DC 20037 englishprograms.state.gov Contents v Introduction vi How Each Entry is Arranged 1 Part 1: Idioms and Definitions 103 Part 2: Selected Idioms by Category 107 Part 3: Classroom Activities 121 Index Introduction Idiom: a group of words that means something In the Loop is a collection of common idioms different than the individual words it contains updated and compiled from two previous books of As with any language, American English is full idioms published by the Office of English Language of idioms, especially when spoken. Idioms Programs: Illustrated American Idioms by Dean add color and texture to language by creating Curry and Something to Crow About by Shelley Vance images that convey meanings beyond those of Laflin. In the Loop combines the popular aspects of the individual words that make them up. Idioms the previous books, while also updating the content are culturally bound, providing insight into the by including idioms that have come into use more history, culture, and outlook of their users. This recently and eliminating those that are rarely used. -

Tennessee Made the Difference CRITICAL FOCUS 5 President’S Message President President Elect Treasurer Secretary Immediate Together Hanson R

Management Counsel: Law Practice 101 Employer Responsibility for Employee or Customer Infections . Page 11 Schooled in Ethics: Tennessee’s Supervised Practice Rule . Page 13 A Monthly Publication of the Knoxville Bar Association | June 2020 WhenWhen RightRight WonWon Out:Out: TennesseeTennessee MadeMade thethe DifferenceDifference 1920-2020 years WOMEN’S VOTE 100CENTENNIAL 2 DICTA June 2020 Officers of the Knoxville Bar Association In This Issue June 2020 COVER STORY 16 When Right Won Out: Tennessee Made the Difference CRITICAL FOCUS 5 President’s Message President President Elect Treasurer Secretary Immediate Together Hanson R. Tipton Cheryl G. Rice Jason H. Long Loretta G. Cravens Past President 7 Around the Bar Wynne du Mariau Finding the Silver Lining KBA Board of Governors Caffey-Knight 9 Practice Tips Covid-19 Business Interruption Sherri DeCosta Alley Elizabeth B. Ford Michael J. Stanuszek and Coverage Litigation: Will the Jamie Ballinger Rachel P. Hurt Amanda Tonkin Pandemic Provide A Wave Of Mark A. Castleberry Allison Jackson Elizabeth M. Towe Potential Coverage Suits in Hon. Kristi Davis Elizabeth (Betsy) Meadows Mikel Towe Robert E. Pryor, Jr. Tennessee? 11 Management Counsel: The Knoxville Bar Association Staff Law Practice 101 Employer Responsibility for Employee or Customer Infections 13 Schooled in Ethics Tennessee’s Supervised Practice Rule 15 Legal Update The Rules They are A-Changin’ WISDOM 6 Legally Weird Marsha S. Watson Tammy Sharpe Jonathan Guess Leslie Rowland All Wild: Cats, Keepers, and a Executive Director CLE