Camuccini, Vincente

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center 6 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 6 Research Reports and Record of Activities I~::':,~''~'~'~ y~ii)i!ili!i.~ f , ".,~ ~ - '~ ' ~' "-'- : '-" ~'~" J:~.-<~ lit "~-~-k'~" / I :-~--' %g I .," ,~_-~ ~i,','~! e 1~,.~ " ~" " -~ '~" "~''~ J a ,k National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 6 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1985--May 1986 Washington, 1986 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1986 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: James Gillray. A Cognocenti Contemplating ye Beauties of ye Antique, 1801. Prints Division, New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foun- dations. CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1985-1986 (June 1985-May 1986) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 17 Meetings 21 Lecture Abstracts 34 Members' Research Reports Reports 38 ~~/3 !i' tTION~ r i I ~ ~. .... ~,~.~.... iiI !~ ~ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

Mattia & Marianovella Romano

Mattia & MariaNovella Romano A Selection of Master Drawings A Selection of Master Drawings Mattia & Maria Novella Romano A Selection of Drawings are sold mounted but not framed. Master Drawings © Copyright Mattia & Maria Novelaa Romano, 2015 Designed by Mattia & Maria Novella Romano and Saverio Fontini 2015 Mattia & Maria Novella Romano 36, Borgo Ognissanti 50123 Florence – Italy Telephone +39 055 239 60 06 Email: [email protected] www.antiksimoneromanoefigli.com Mattia & Maria Novella Romano A Selection of Master Drawings 2015 F R FRATELLI ROMANO 36, Borgo Ognissanti Florence - Italy Acknowledgements Index of Artists We would like to thank Luisa Berretti, Carlo Falciani, Catherine Gouguel, Martin Hirschoeck, Ellida Minelli, Cristiana Romalli, Annalisa Scarpa and Julien Stock for their help in the preparation of this catalogue. Index of Artists 15 1 3 BARGHEER EDUARD BERTANI GIOVAN BAttISTA BRIZIO FRANCESCO (?) 5 9 7 8 CANTARINI SIMONE CONCA SEBASTIANO DE FERRARI GREGORIO DE MAttEIS PAOLO 12 10 14 6 FISCHEttI FEDELE FONTEBASSO FRANCESCO GEMITO VINCENZO GIORDANO LUCA 2 11 13 4 MARCHEttI MARCO MENESCARDI GIUSTINO SABATELLI LUIGI TASSI AGOSTINO 1. GIOVAN BAttISTA BERTANI Mantua c. 1516 – 1576 Bacchus and Erigone Pen, ink and watercoloured ink on watermarked laid paper squared in chalk 208 x 163 mm. (8 ¼ x 6 ⅜ in.) PROVENANCE Private collection. Giovan Battista Bertani was the successor to Giulio At the centre of the composition a man with long hair Romano in the prestigious work site of the Ducal Palace seems to be holding a woman close to him. She is seen in Mantua.1 His name is first mentioned in documents of from behind, with vines clinging to her; to the sides of 1531 as ‘pictor’, under the direction of the master, during the central group, there are two pairs of little erotes who the construction works of the “Palazzina della Paleologa”, play among themselves, passing bunches of grapes to each which no longer exists, in the Ducal Palace.2 According other. -

The Men of Letters and the Teaching Artists: Guattani, Minardi, and the Discourse on Art at the Accademia Di San Luca in Rome in the Nineteenth Century

The men of letters and the teaching artists: Guattani, Minardi, and the discourse on art at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome in the nineteenth century Pier Paolo Racioppi The argument of whether a non-artist was qualified to write about art famously dates back as far as the Renaissance.1 Through their writings, Cennino Cennini (c. 1360-before 1427), Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), and Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) consolidated the auctoritas of artists by developing a theoretical discourse on art.2 Two centuries later, Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779), who was also Prince of the Accademia di San Luca between 1771 and 1772, even achieved the title of ‘philosopher-painter.’3 As for men of letters, the classicist theory of the Horatian ut pictura poesis, the analogy of painting and poetry, allowed them to enter the field of art criticism. From the Renaissance onwards, the literary component came to prevail over the visual one. As Cristopher Braider writes, the two terms of the equation ‘as painting, so poetry’ were ultimately reversed in ‘as poetry, so painting’,4 and consequently ‘it is to this reversal that we owe the most salient and far-reaching features of ut pictura aesthetics’.5 Invention, a purely intellectual operation of conceiving the subject (as in Aristotle’s Poetics and Rhetoric), thus rests at the base of the creative process for both poetry and painting. Consequently, due to its complex inherent features, history painting became the highest form of invention and the pinnacle of painting genres, according to the Aristotelian scheme of the Poetics (ranging from the representation of the inanimate nature to that of the human actions) as applied to the visual arts.6 I am grateful to Angela Cipriani and Stefania Ventra for their comments and suggestions. -

Selected Works from 18Th to 20Th Century

SELECTED WORKS From 18th to 20th CENTURY GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & C0. GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & Co. ARTE ANTICA MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA Edition curated by Stefano Grandesso in collaboration with Eugenio Maria Costantini Aknowledgements Franco Barbieri, Bernardo Falconi, Massimo Negri English Translations Daniel Godfrey, Michael Sullivan Photo Credits Photographs were provided by the owners of the works, both institutions and individuals. Additional information on photograph sources follows. Arte Fotografica, Rome, pp. 4, 7, 9, 13-19, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 43, 45, 47, 57, 61-63, 67, 69, 71, 73, 75, 77-79, 81, 83, 85, 88 Foto Claudio Falcucci, p. 25 Foto Giusti Claudio, Lastra a Signa, p. 35 Giulio Archinà per StudioPrimoPiano, p. 23 Paolo e Federico Manusardi, Milano, pp. 39, 41 The editor will be pleased to honor any outstanding royalties concerning the use of photographic images that it has so far not been possible to ascertain. ISBN 978-88-942099-4-5 © Edizioni del Borghetto Tel. + 39 06 6871093 - Fax +39 06 68130028 e-mail: [email protected] http//www.carlovirgilio.it SELECTED WORKS From 18th to 20th CENTURY Catalogue entries Adriano Amendola, Manuel Carrera, Eugenio Maria Costantini, Federica Giacomini, Cristiano Giometti, Stefano Grandesso, Silvia Massari, Fernando Mazzocca, Hermann Mildenberger, Giuseppe Porzio, Serenella Rolfi Ožvald, Valeria Rotili, Annalisa Scarpa, Ilaria Sgarbozza, Ettore Spalletti, Nicola Spinosa TEFAF Maastricht March 16–24, 2019 e GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & Co. ARTE ANTICA MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA ISBN 978-88-942099-4-5 Via della Lupa, 10 - 00186 Roma 59 Jermyn Street, Flat 5 - London SW1Y 6LX Tel. +39 06 6871093 [email protected] - [email protected] www.carlovirgilio.it Detail of cat. -

European Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture 1770 – 1930

CATALOG-17-Summer_CATALOG/04/Summer 5/4/17 10:20 AM Page 1 EUROPEAN PAINTINGS, WATERCOLORS, DRAWINGS AND SCULPTURE 1770 – 1930 May 23 rd through July 28 th 2017 Catalog by Robert Kashey, David Wojciechowski, and Stephanie Hackett Edited by Elisabeth Kashey SHEPHERD W & K GALLERIES 58 East 79th Street New York, N. Y. 10075 Tel: 1 212 861 4050 Fax: 1 212 772 1314 [email protected] www.shepherdgallery.com CATALOG-17-Summer_CATALOG/04/Summer 5/4/17 10:20 AM Page 2 © Copyright: Robert J. F. Kashey for Shepherd Gallery, Associates, 2017 COVER ILLUSTRATION: Felice Giani, Achates and Ascanius Bringing Gifts to the Tyrians , circa 1810, cat. no. 8 GRAPHIC DESIGN: Keith Stout PHOTOGRAPHY: Brian Bald TECHNICAL NOTES: All measurements are in inches and in centimeters; height precedes width. All drawings and paintings are framed. Prices on request. All works subject to prior sale. SHEPHERD GALLERY SERVICES has framed, matted, and restored all of the objects in this exhibition, if required. The Service Department is open to the public by appointment, Tuesday though Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Tel: (212) 744 3392; fax (212) 744 1525; e-mail: [email protected]. CATALOG-17-Summer_CATALOG/04/Summer 5/4/17 10:20 AM Page 3 CATALOG CATALOG-17-Summer_CATALOG/04/Summer 5/4/17 10:20 AM Page 4 1 LABRUZZI, Carlo 1747/48 - 1818 Italian School EMPEROR GALBA’S TOMB, 1789 Watercolor and pencil with brown ink double framing lines on lightweight, beige, laid paper, indecipherable watermark. 16 1/8” x 21 3/4” (40.9 x 55.2 cm). -

Angelica Kauffmann, R.A., Her Life and Her Works

EX LlBRl THE GETTY PROVENANCE INDEX This edition is limited to lOOO copies for sale in Great Britain and the United States. I ANGELICA KAUFFMANN, R.A. HER LIFE AND HER WORKS BT DR. G. C. WILLIAMSON THE KEATS LETTERS, PAPERS AND OTHER RELICS Reproduced in facsimile from the late Sir Charles Dilke's Bequest to the Corporation of Hampstead. Foreword by Theodore Watts-Dunton and an Intro- duction by H. Buxton Forman. With 8 Portraits of Keats, and 57 Plates in collotype. Limited to 320 copies. Imperial 4to. OZIAS HUMPHRY: HIS LIFE AND WORKS With numerous Illustrations in colour, photogravure and black and white. Demy 410. MURRAY MARKS AND HIS FRIENDS With numerous Illustrations. Demy 8vo. DANIEL GARDNER Painter in Pastel and Gouache. A Brief Account of His Life and Works. With 9 Plates in colour, 6 photogravures, and very numerous reproductions in half-tone. Demy 4to. THE JOHN KEATS MEMORIAL VOLUME By various distinguished writers. Edited by Dr. G. C. Williamson. Illustrated. Crown 410. Dr. G. C. WILLUMSON and LADY VICTORIA MANNERS THE LIFE AND WORK of JOHN ZOFFANY, R.A. With numerous Illustrations in photogravure, colour and black and white. Limited to 500 copies. Demy 4to. THE BODLEY HEAD Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/angelicakauffmanOOmann SELF PORTRAIT OF ANGELICA. From the original painting in the possessio?! of the Duke of Rutland and hanging at Belvoir Castle. The Duke also owns the original sketchfor this portrait. ANGELICA KAUFFMANN, R.A. HER LIFE AND HER WORKS By LADY VICTORIA MANNERS AND Dr. G. -

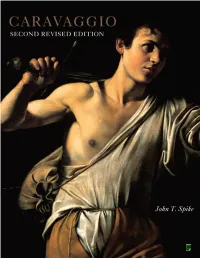

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Giovanni Battista Camuccini Magic Land

Francesca Antonacci Damiano Lapiccirella Fine Art Francesca Antonacci Damiano Lapiccirella Fine Art E’ ormai trascorso del tempo da quando un amico, It was quite some time ago now that a friend whose nasce dalla fusione di due storiche gallerie, con sede is the result of a merger between two old-established del quale è cara la memoria a quanti lo conobbero, memory is treasured by all those who knew him gave FINE ART rispettivamente a Roma-Londra e a Firenze, che antique galleries based in Rome – London and mi fece dono del catalogo della Gere Collection alla me the catalogue of the Gere Collection in the National sono state tra i principali punti di riferimento sia del Florence respectively, both leading lights in the world londinese National Gallery. Donare, inteso come Gallery in London as a gift. Gifts are one of life’s joys, collezionismo italiano che internazionale fin dagli of Italian and international collecting since the early T dare o ricevere, è una delle gioie della vita: il dono both in the giving and the receiving: they are a state inizi del 1900. 1900s. come stato d’animo. of mind. FINE AR La galleria, nel corso degli anni, è diventata un The Galleria Francesca Antonacci Damiano Ma a chi scrive, cultore anziano della pittura di But for me, a long-time devotee of landscape painting, punto di riferimento per gli appassionati di dipinti Lapiccirella Fine Art has become a focal point over paesaggio, quel dono recava anche il valore e il that gift also held the value and the significance of a A L A del ‘Grand Tour’, disegni e sculture di artisti europei the years for enthusiasts and collectors of paintings of Giovanni Battista Camuccini significato di una scoperta. -

Quadreria (1750-1850)

A PICTURE GALLERY IN THE ITALIAN TRADITION OF THE QUADRERIA (1750-1850) SPERONE WESTWATER 2 A PICTURE GALLERY IN THE ITALIAN TRADITION OF THE Q UADRERIA (1750-1850) SPERONE WESTWATER 2 A PICTURE GALLERY IN THE ITALIAN TRADITION OF THE QUADRERIA (1750-1850) 10 January - 23 February 2013 curated by Stefano Grandesso, Gian Enzo Sperone and Carlo Virgilio Essay by Joseph J. Rishel catalogue edited by Stefano Grandesso SPERONE WESTWATER in collaboration with GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & CO. - ROME (cat. no. 15) This catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition A Picture Gallery in the Italian Tradition of the Quadreria* (1750-1850), presented at Sperone Westwater, New York, 10 January through 23 February, 2013. 257 Bowery, New York, NY 10002 *A quadreria is a specifically Italian denomination for a collection of pictures (quadri) up to and beyond the eighteenth century, with the pictures normally covering the entire wall space from floor to ceiling. Before the advent of the illuminist concept of the picture gallery (pinacoteca), which followed a classification based on genre and chronology suitable for museums or didactic purposes, the quadreria developed mainly according to personal taste, affinity and reference to the figurative tradition. Acknowledgements Leticia Azcue Brea, Liliana Barroero, Walter Biggs, Emilia Calbi, Giovanna Capitelli, Andrew Ciechanowiecki, Stefano Cracolici, Guecello di Porcia, Marta Galli, Eileen Jeng, Alexander Johnson, David Leiber, Nera Lerner, Todd Longstaffe-Gowan, Marena Marquet, Joe McDonnell, Roberta Olson, Ann Percy, Tania Pistone, Bianca Riccio, Mario Sartor, Angela Westwater Foreword Special thanks to Maryse Brand for editing the texts by Joseph J. Rishel English translation Luciano Chianese Photographic Credits Arte Fotografica, Roma Studio Primo Piano di Giulio Archinà Marino Ierman, Trieste The editor will be pleased to honor any outstanding royalties concerning the use of photographic images that it has so far not been possible to ascertain. -

Vincenzo Camuccini E I Maestri Dell'accademia Di San Luca

Vincenzo Camuccini e i Maestri dell’Accademia di San Luca Il racconto storico nella pittura dell’Ottocento a cura di Rocambole Garufi Vincenzo Camuccini Direttore della romana Accademia di San Luca, dove Sebastiano Guzzone fu allievo diverse volte premiato, Vincenzo Camuccini ebbe un’importanza notevolissima nell’impostazione “teatrale” dei quadri italiani. Si pensi, per capirlo, ai “Vespri siciliani” del veneziano Francesco Hayez, tanto frainteso da Giulio Carlo Argan nel suo sopravvalutato manuale (L’arte moderna). In effetti, mettere a paragone la pittura di un David con la coeva pittura italiana appare piuttosto scorretto, se si tiene conto della cultura dei due popoli. L’Italia, più che in una dimensione storica, ha trovato la sua vera identità nello spettacolo, inteso come “recita” della Storia e dei valori condivisi. L’Italia è la terra del melodramma e della novellistica (si pensi, per l’Ottocento al Di Giacomo, al Fucini, al Verga… fino ad arrivare allo stesso Pirandello). Non c’è, in Italia, il comune sentire dei forti scontri sociali o identitari. Possono esserci vampate ribellistiche, ma certamente non la sistematica, e troppo spesso tragica, coerenza dei francesi, dei russi, dei tedeschi. Guzzone ne fu un interprete eccelso – superando lo stesso Camuccini e, in parte, lo Hayez -, perché cosciente delle dimensione “colloquiale” che da noi ha il discorso artistico. Solo alla luce di questa premessa vale la pena di riscoprirne l’opera… soprattutto mettendo da parte i principali nemici di ogni vera cultura: i narcisismi provinciali, le arbitrarie superbie delle caste culturali, la barbarie di essere sordi alle voci non acquisite al sistema. -

QUADRERIA 2015 Documents D’Art Et D’Histoire

GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & C. VIRGILIO CARLO QUADRERIA 2015 Documents d’art et d’histoire QUADRERIA 2015 QUADRERIA GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & C. GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & C. ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA Traduction en français Barbara Musetti Crédits photographiques Arte fotografica, Roma, plates Archivio dell’Arte / Luciano Pedicini, p. 30, fig. 2 Archivio Fotografico della Soprintendenza BEAP di Parma e Piacenza, p. 28, fig. 1 ; p. 30, fig. 3 Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Lucca, p. 15, fig. 3 ; p. 24, fig. 2 Fondazione Federico Zeri, Fototeca, Università di Bologna, p. 12, fig. 1 Giulio Archinà per StudioPrimoPiano, p. 36, fig. 2 ©Museo Nacional del Prado, p. 16, fig. 1, 2 Sotheby’s, New York, p. 14, fig. 2 L’éditeur est à la disposition des éventuels ayants droit qu’il n’a pas été possible de retrouver Nos remerciements s’adressent tout particulièrement à Andrea Bacchi, Alberto Barsi, Dario De Stefano, Bernardo Falconi, Graziano Gallo, Roberto Giovannelli, Diego Gomiero, Francesco Leone, Angelo Loda, Alessandro Malinverni, Mario Marubbi, Fernando Mazzocca, Filippo Orsini, Stefania Paradiso, Simonetta Pozzolini, Andrea Robino Rizzet, Gian Battista Vannozzi, Annarita Ziveri. ISBN 978-88-908176-9-4 © Edizioni del Borghetto Tel. + 39 06 6871093 - Fax +39 06 68130028 e-mail: [email protected] http//www.carlovirgilio.it QUADRERIA 2015 Documents d’art et d’histoire sous la direction de Giuseppe Porzio Paris Tableau Palais Brongniart, Place de la Bourse, Paris 2e 11-15 novembre 2015 e ISBN 978-88-908176-9-4 GALLERIA CARLO VIRGILIO & C. Arte moderna e contemporanea Via della Lupa, 10 - 00186 Roma Tel. +39 06 6871093 - Fax + 39 06 68130028 [email protected] www.carlovirgilio.it Présentation e nouveau chapitre de la série Quadreria confirme la sensibilité comme Cle goût, attentifs aux aspects les plus recherchés et les plus originaux de la production artistique, qui caractérisent depuis toujours la Galerie Carlo Virgilio. -

The Capitol Dome

Fig. 1A. Detail of carved relief with swan and rinceaux on the Ara Pacis, Rome. [credit] Photograph by author SPECIAL EDITION THE CAPITOL DOME CELEBRATING Constantino Brumidi’s Life and Art A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 51 , NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 The next special issue of The Capitol Dome will be devoted to the bicentennial of the War of 1812 and specifically the fate of the United States Capitol in 1814, when combined British naval and land forces captured Washington, DC and set fire to many public buildings. The mural (above) from the Hall of Capitols by Allyn Cox in the House wing of the Capitol illustrates the burning Capitol in the background. USCHS BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Richard Baker, Ph.D. Hon. Kenneth E. Bentsen, Jr. Ken Bowling, Ph.D. Hon. Richard Burr Nicholas E. Calio UNITED STATES CAPITOL Donald G. Carlson ----------- Hon. E. Thomas Coleman HISTORICAL SOCIETY L. Neale Cosby Scott Cosby Nancy Dorn George C. “Bud” Garikes Bruce Heiman Hon. Richard Holwill Tim Keating Hon. Dirk Kempthorne Contents Hon. John B. Larson Jennifer LaTourette Rob Lively Tamera Luzzatto Tim Lynch Norm Ornstein, Ph.D. Beverly L. Perry David Regan Rome Brought to Washington in Brumidi’s Murals for the Cokie Roberts Hon. Ron Sarasin United States Capitol Mark Shields by Barbara Wolanin..................................................................2 Dontai Smalls William G. Sutton, CAE Tina Tate Hon. Ellen O’Kane Tauscher The American Artist as Scientist: Constantino Brumidi’s James A. Thurber, Ph.D. Hon. Pat Tiberi Fresco of Robert Fulton for the United States Capitol Connie Tipton by Thomas P.