Who Represents the Poor? the Corrective Potential of Populism in Spain*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation by Chunta Aragonesista (CHA) on the Situation of the Aragonese Minority Languages (Aragonese and Catalan)

Presentation by Chunta Aragonesista (CHA) on the situation of the Aragonese minority languages (Aragonese and Catalan) European Parliament Intergroup on Traditional Minorities, National Communities and Languages Strasbourg, 24 May 2012 Aragon is one of the historical nations on which the current Spanish State was set up. Since its origins back in the 9 th century in the central Pyrenees, two languages were born and grew up on its soil: Aragonese and Catalan (the latter originated simultaneously in Catalonia as well as in some areas that have always belonged to Aragon). Both languages expanded Southwards from the mountains down to the Ebro basin, Iberian mountains and Mediterranean shores in medieval times, and became literary languages by their use in the court of the Kings of Aragon, who also were sovereigns of Valencia, Catalonia and Majorca. In the 15 th century a dynastic shift gave the Crown of Aragon to a Castilian prince. The new reigning family only expressed itself in Castilian language. That fact plus the mutual influences of Castilian and Aragonese through their common borders, as well as the lack of a strong linguistic awareness in Aragon facilitated a change in the cultural trends of society. From then on the literary and administrative language had to be Castilian and the old Aragonese and Catalan languages got relegated in Aragon mostly to rural areas or the illiterate. That process of ‘glottophagy’ or language extinction sped up through the 17 th and 18 th centuries, especially after the conquest of the country by the King Philip of Bourbon during the Spanish War of Succession and its annexation to Castile. -

Second-Order Elections: Everyone, Everywhere? Regional and National Considerations in Regional Voting

Liñeira, R. (2016) Second-order elections: everyone, everywhere? Regional and national considerations in regional voting. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 46(4), pp. 510- 538. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/219966/ Deposited on: 15 July 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Second-order Elections: Everyone, Everywhere? Regional and National Considerations in Regional Voting Robert Liñeira University of Edinburgh [email protected] Abstract: Vote choice in regional elections is commonly explained as dependent on national politics and occasionally as an autonomous decision driven by region-specific factors. However, few arguments and little evidence have been provided regarding the determinants that drive voters’ choices to one end or the other of this dependency-autonomy continuum. In this article we claim that contextual and individual factors help to raise (or lower) the voters’ awareness of their regional government, affecting the scale of considerations (national or regional) they use to cast their votes at regional elections. Using survey data from regional elections in Spain, we find that voters’ decisions are more autonomous from national politics among the more politically sophisticated voters, among those who have stronger feelings of attachment to their region, and in those contexts in which the regional incumbent party is different from the national one. In their landmark article Reif and Schmitt (1980) drew a distinction between first and second- order elections. -

Document Downloaded From: the Final Publication Is Available At

Document downloaded from: http://hdl.handle.net/10459.1/67539 The final publication is available at: https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.00045.tor © John Benjamins Publishing, 2019 The Legal Rights of Aragonese-Speaking Schoolchildren: The Current State of Aragonese Language Teaching in Aragon (Spain) Aragon is an autonomous community within Spain where, historically, three languages are spoken: Aragonese, Catalan, and Castilian Spanish. Both Aragonese and Catalan are minority and minoritised languages within the territory, while Castilian Spanish, the majority language, enjoys total legal protection and legitimation. The fact that we live in the era of the nation-state is crucial for understanding endangered languages in their specific socio-political context. This is why policies at macro-level and micro-level are essential for language maintenance and equality. In this article, we carry out an in-depth analysis of 57 documents: international and national legal documents, education reports, and education curricula. The aims of the paper are: 1) to analyse the current state of Aragonese language teaching in primary education in Aragon, and 2) to suggest solutions and desirable policies to address the passive bilingualism of Aragonese- speaking schoolchildren. We conclude that the linguistic diversity of a trilingual autonomous community is not reflected in the real life situation. There is also a need to Comentado [FG1]: Syntax unclear, meaning ambiguous implement language policies (bottom-up and top-down initiatives) to promote compulsory education in a minoritised language. We therefore propose a linguistic model that capitalises all languages. This study may contribute to research into Aragonese- Comentado [FG2]: Letters can be capitalized, but not languages. -

Multilevel Electoral Competition: Regional Elections and Party Systems in Spain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadmus, EUI Research Repository Multilevel Electoral Competition: Regional Elections and Party Systems in Spain Francesc Pallarés and Michael Keating Abstract Regionalisation in the form of the creation of Autonomous Communities (ACs) has played a significant role in shaping the Spanish party system since the transition to democracy in 1977. Parties are divided into state-wide parties, operating at both national and regional levels, and non state-wide parties. The latter are most important in the historic nations of Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia. Autonomous elections are generally second order elections, with lower turnout and with results generally following the national pattern. In certain cases, the presence of non-state wide parties challenges this pattern and in Catalonia a distinct political arena exists with its own characteristics. Autonomous parliaments and governments have provided new opportunities for both state-wide and non-state-wide parties and served as a power base for political figures within the parties. 2 Introduction The reconfiguration of Spain as an Estado de las autonomías (state of the autonomies) has produced multiple arenas for political competition, strategic opportunities for political actors, and possibilities for tactical voting. We ask how the regional level fits into this pattern of multilevel competition; what incentives this provides for the use of party resources; how regionalisation has affected the development of political parties; how these define their strategies in relation to the different levels of party activity and of government; how these are perceived by electors and affect electoral behaviour; and whether there are systematic differences in electoral behaviour at state and regional levels. -

Basque Political Systems

11m_..... ·· _~ ~ - -= ,_.... ff) • ' I I -' - i ~ t I V Center for Basque Studies - University of Nevada, Reno BASQUE POLITICS SERIES Center for Basque Studies Basque Politics Series, No. 2 Basque Political Systems Edited by Pedro Ibarra Güell and Xabier Irujo Ametzaga Translated by Cameron J. Watson Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support from the Basque government. Center for Basque Studies Basque Politics Series, No. 2 Series Editor: Xabier Irujo Ametzaga Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover and Series design © 2011 Jose Luis Agote. Cover Illustration: Juan Azpeitia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Basque political systems / edited by Pedro Ibarra G?ell, and Xabier Irujo Ametzaga ; translated by Cameron J. Watson. p. cm. -- (Basque politics series ; No. 2) Includes index. Summary: “Collection of articles on the Basque political system within its own context and larger national and global contexts”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-935709-03-9 (pbk.) 1. País Vasco (Spain)--Politics and government. I. Ibarra Güell, Pedro. II. Irujo Ame- tzaga, Xabier. JN8399.P342B37 2011 320.446’6--dc22 2011001811 CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................... 7 PEDRO IBARRA GÜELL and XABIER IRUJO AMETZAGA 1. Hegoalde and the Post-Franco Spanish State ................................... 13 XABIER IRUJO AMETZAGA 2. Political Institutions in Hegoalde................................................ 33 MIKEL IRUJO AMETZAGA 3. Political Institutions and Mobilization in Iparralde ............................. 53 IGOR AHEDO GURRUTXAGA 4. Fiscal Pacts in Hegoalde ........................................................ -

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament Elections Since 1979 Codebook (July 31, 2019)

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament elections since 1979 Vincenzo Emanuele (Luiss), Davide Angelucci (Luiss), Bruno Marino (Unitelma Sapienza), Leonardo Puleo (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna), Federico Vegetti (University of Milan) Codebook (July 31, 2019) Description This dataset provides data on electoral volatility and its internal components in the elections for the European Parliament (EP) in all European Union (EU) countries since 1979 or the date of their accession to the Union. It also provides data about electoral volatility for both the class bloc and the demarcation bloc. This dataset will be regularly updated so as to include the next rounds of the European Parliament elections. Content Country: country where the EP election is held (in alphabetical order) Election_year: year in which the election is held Election_date: exact date of the election RegV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties that enter or exit from the party system. A party is considered as entering the party system where it receives at least 1% of the national share in election at time t+1 (while it received less than 1% in election at time t). Conversely, a party is considered as exiting the part system where it receives less than 1% in election at time t+1 (while it received at least 1% in election at time t). AltV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between existing parties, namely parties receiving at least 1% of the national share in both elections under scrutiny. OthV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties falling below 1% of the national share in both the elections at time t and t+1. -

Digital Communication and Politics in Aragon. a Two-Way Communication Formula for the Interaction Between Politicians and Citizens

Cabezuelo-Lorenzo, F. and Ruiz-Carreras, ... 1 Pages 340 to 353 Research - How to cite this article – referees' reports – scheduling – metadata – PDF – Creative Commons DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-65-2010-904-340-353-EN – ISSN 1138 - 5820 – RLCS # 65 – 2010 Digital Communication and Politics in Aragon. A two-way communication formula for the interaction between politicians and citizens Francisco Cabezuelo-Lorenzo, Ph.D. [C.V.] Associate Professor - San Pablo-CEU University - Madrid - [email protected] María Ruiz-Carreras [C. V.] Ph.D. Student - Rey Juan Carlos University - Madrid - [email protected] Abstract: This research presents blogs as an innovative and rich tool for political communication. Blogs can facilitate two-way communication and true interaction between citizens and politicians. The article analyses in depth the content, uses, and characteristics of five weblogs written by Aragonese politicians. Although the study detects some weaknesses in the current political use of blogs, it encourages political parties to use blogs and other online resources, not only during electoral campaigns to improve the reputation of political leaders but also continuously and particularly in situations of special interest for the citizenship. The study shows that the use of blogs by Aragonese politicians is no longer just a transitory phenomenon and has become a reality. The article also demonstrates that politicians use blogs mostly as a pre-electoral tooland to a much lesser extent as an element of communication to promote democracy. It has been observed that politicians’ blogs are used as a tool to overcome situations of crisis and to compensate negative opinions caused by questionable acts. -

El Caso Bildu»: Continuidad Y Ruptura En La Doctrina Del Tribunal Constitucional Sobre La Ilegalización De Formaciones Políticas

Este revista forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx «EL CASO BILDU»: CONTINUIDAD Y RUPTURA EN LA DOCTRINA DEL TRIBUNAL CONSTITUCIONAL SOBRE LA ILEGALIZACIÓN DE FORMACIONES POLÍTICAS MERCEDES IGLESIAS BÁREZ Profesora Contratada Doctora de Derecho Constitucional Universidad de Salamanca SUMARIO. I. Introducción II. Las características procesales de la prohibición de presentación de candidaturas en el Caso Bildu III. La doctrina constitucional en materia de suce- sión fraudulenta de partidos políticos ilegali- zados y disueltos (art. 44.4 LOREG). Su apli- cación al Caso Bildu I. INTRODUCCIÓN Han transcurridos ocho años ya desde que la Sala Especial del Tribunal Supremo de- clarara, mediante Sentencia de 27 de marzo de 20031, la ilegalización y disolución de los partidos políticos Euskal Herritarrok, Herri Batasuna y Batasuna, al acreditarse fehacien- temente que estas formaciones políticas habían incurrido en la causa establecida en el art. 10. 2 c) de la Ley 6/2002, de 27 de junio, de Partidos Políticos, que habilita a la Sala Es- pecial a decretar la disolución de un partido «cuando de forma reiterada y grave su activi- dad vulnere los principios democráticos o persiga deteriorar o destruir el régimen de li- bertades o imposibilitar o eliminar el sistema democrático, mediante las conductas a que se refiere el art. 9 de la Ley». A pesar de la Sentencia de disolución, Batasuna ha intentado re- 1 El Tribunal Constitucional, como es bien sabido, desestimó los recursos de amparo interpuestos en su momento en virtud de las SSTC 5/2004 y 6/2004, ambas de 16 de enero. -

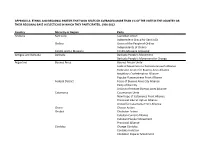

Appendix A: Ethnic and Regional Parties That Won

APPENDIX A: ETHNIC AND REGIONAL PARTIES THAT WON SEATS OR AVERAGED MORE THAN 1% OF THE VOTE IN THE COUNTRY OR THEIR REGIONAL BASE IN ELECTIONS IN WHICH THEY PARTICIPATED, 1990-2012 Country Minority or Region Party Andorra Sant Julià Lauredian Union Independent Group for Sant Julià Ordino Union of the People of Ordino Independents of Ordino Canillo and La Massana Canillo-Massana Grouping Antigua and Barbuda Barbuda Barbuda People's Movement Barbuda People's Movement for Change Argentina Buenos Aires Buenos Airean Unity Federal Movement to Recreate Growth Alliance Federalist Action for Buenos Aires Alliance Neighbors Confederation Alliance Popular Bueonsairean Front Alliance Federal District Force of Buenos Aires City Alliance Party of the City Union to Recreate Buenos Aires Alliance Catamarca Catamarcan Unity New Hope of Catamarca Front Alliance Provincial Liberal Option Alliance United for Catamarca Front Alliance Chaco Chacan Action Chubut Chubutan Action Cubutan Current Alliance Cubutan Popular Movement Provincial Alliance Córdoba Change Córdoba Córdoba in Action Córdoban Popular Movement Country Minority or Region Party The People First – Neighborly Union of Córdoba Alliance Together for Córdoba Alliance Union for Córdoba Alliance Corrientes Autonomous Liberal Pact-Popular Democratic Autonomous Liberal Pact-Progressive Democrat- Christian Democrat Civic and Social Front of Corrientes Corrientan Action Corrientan Front Corrientes Project Front Alliance Liberal-Autonomist Pact-Progressive Democratic-Union of the Democratic Center Alliance -

El Caso Bildu»: Continuidad Y Ruptura En La Doctrina Del Tribunal Constitucional Sobre La Ilegalización De Formaciones Políticas

«EL CASO BILDU»: CONTINUIDAD Y RUPTURA EN LA DOCTRINA DEL TRIBUNAL CONSTITUCIONAL SOBRE LA ILEGALIZACIÓN DE FORMACIONES POLÍTICAS MERCEDES IGLESIAS BÁREZ Profesora Contratada Doctora de Derecho Constitucional Universidad de Salamanca SUMARIO. I. Introducción II. Las características procesales de la prohibición de presentación de candidaturas en el Caso Bildu III. La doctrina constitucional en materia de suce- sión fraudulenta de partidos políticos ilegali- zados y disueltos (art. 44.4 LOREG). Su apli- cación al Caso Bildu I. INTRODUCCIÓN Han transcurridos ocho años ya desde que la Sala Especial del Tribunal Supremo de- clarara, mediante Sentencia de 27 de marzo de 20031, la ilegalización y disolución de los partidos políticos Euskal Herritarrok, Herri Batasuna y Batasuna, al acreditarse fehacien- temente que estas formaciones políticas habían incurrido en la causa establecida en el art. 10. 2 c) de la Ley 6/2002, de 27 de junio, de Partidos Políticos, que habilita a la Sala Es- pecial a decretar la disolución de un partido «cuando de forma reiterada y grave su activi- dad vulnere los principios democráticos o persiga deteriorar o destruir el régimen de li- bertades o imposibilitar o eliminar el sistema democrático, mediante las conductas a que se refiere el art. 9 de la Ley». A pesar de la Sentencia de disolución, Batasuna ha intentado re- 1 El Tribunal Constitucional, como es bien sabido, desestimó los recursos de amparo interpuestos en su momento en virtud de las SSTC 5/2004 y 6/2004, ambas de 16 de enero. UNED. Teoría y Realidad Constitucional, núm. 28, 2011, pp. 555-578. 556 MERCEDES IGLESIAS BÁREZ constituirse políticamente en fraude de ley sirviéndose de otras entidades políticas (agru- paciones de electores, partidos ya existentes o creados ex novo), que le permitieran seguir par- ticipando en los procesos electorales y llegar así a las instituciones políticas. -

List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2015a from May 22, 2015 Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset Version 2015a 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the party’s or alliance’s name in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list by themselves. If the composition of an alliance changed between different elections, this change is covered as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party was a split from another party or a merger of a number of other parties and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 1.1 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. -

The Ebro in Aragonesismo and Aragonese Nationalism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link THE EBRO IN ARAGONESISMO AND ARAGONESE NATIONALISM BRENDA REED PhD NOVEMBER 2010 NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES MODERN LANGUAGES DIVISION PhD DISSERTATION THE EBRO IN ARAGONESISMO AND ARAGONESE NATIONALISM BRENDA REED Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Northumbria University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SUBMISSION DATE: NOVEMBER 2010 ABSTRACT Since the 1970s Aragon has been at the centre of heated controversies over central government proposals to transfer water from the Ebro to Spain’s Mediterranean coastal regions and the scene of numerous mass demonstrations in opposition to these. Throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries the Ebro has been used and perceived by Aragonese regionalism, nationalism and aragonesismo in a variety of ways. This gives rise to the possibility that opposition to the transfer of water from the Ebro goes beyond purely economic and environmental considerations and evokes deeper nationalistic aspects which see it as an essential element of Aragonese identity, patrimonial wealth and natural national heritage. The Ebro had a prominent place in the thinking of the early twentieth century nationalist group as a life-giver and father figure of Aragonese identity and a symbol of territory, homeland, regional development and patrimonial wealth. Later defence of the Ebro against proposed water transfers has been used by Aragonese