Burkes Pass Scenic Reserve Predator Stomach Content Analysis for 2010-2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TS2-V6.0 11-Aoraki

Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve, New Zealand Margaret Austin, John Hearnshaw and Alison Loveridge 1. Identification of the property 1.a Country/State Party: New Zealand 1.b State/Province/Region: Canterbury Region, Te Manahuna / Mackenzie Basin 1.c Name: Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 1.d Location The geographical co-ordinates for the two core sites are: • Mt John University Observatory near Tekapo: latitude 43° 59′ 08″ S, longitude 170° 27′ 54″ E, elevation 1030m above MSL. • Mt Cook Airport and including the White Horse Hill Camping Ground near Aoraki/Mt Cook village: latitude 43° 46′ 01″ S, longitude 170° 07′ 59″ E, elevation 650m above MSL. Fig. 11.1. Location of the property in New Zealand South Island. Satellite photograph showing the locations of Lake Tekapo (A) and the Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park (B). Source: Google Earth 232 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.e Maps and Plans See Figs. 11.2, 11.3 and 11.4. Fig. 11.2. Topographic map showing the primary core boundary defined by the 800m contour line Fig. 11.3. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boun- daries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 233 Fig. 11.4. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boundaries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary 234 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.f Area of the property Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve is located in the centre of the South Island of New Zealand, in the Canterbury Region, in the place known as Te Manahuna or the Mackenzie Basin (see Fig. -

MAC7 2017 Mackenzie A&P Schedule.Indd

MACKENZIE A & P SHOW SCHEDULE OF CLASSES 123rd Annual Mackenzie Highland Show to be held on the Showgrounds in Fairlie On Easter Monday, 5th April 2021 Mackenzie A & P Society P.O. Box 53, Fairlie 7949 TELEPHONE: 021-713-033 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: mackenzieshow.co.nz FACEBOOK: facebook.com/mackenzieshow Pre-Sale Entry Tickets Available Online Adults: $15, Children aged 5-15 yrs: $5 Pre-schoolers and Car Parking: FREE Pre-Sale Ringside Parking Permit: $50 Pre-Booked Disabled Parking Permit: FREE EFTPOS, food and beverages available on grounds. PRESIDENT: Mr David Taylor VICE PRESIDENT: Mr Mark Davis JUNIOR VICE PRESIDENT: Mr Chris Hampton SECRETARY: Mrs Jodi Payne Thank you to our Major Sponsors: Alpine Energy, Barwoods, Des Segar Motors 2006 & Auto Trans, Fairlie Early Learners, Farmlands, Farm Source, Four Square Fairlie, Goldpine, Hazlett, Heiniger New Zealand Ltd, Lemacon Ltd, LJ Hooker, Mackenzie Supply Services, Mainland Wools, Makikihi Fries Chip Factory, Meadowslea Stud, Meridian Energy, Mighty Mix Dog Food, Mitre 10, Peppers Bluewater Resort, Peter Walsh & Associates, PGG Wrightson Wool Ltd, Point Lumber, Property Brokers, Ravensdown Fertiliser Co-Op, South Canterbury Toyota, The Front Store Engineering Supplies/Andar, Wasteaway INVITATION TO VISIT THE 123rd MACKENZIE HIGHLAND A & P SHOW To continue in the tradition of past years and accentuated at our Centennial Show, you and your family are encouraged to wear the traditional highland dress - the kilt, which will add colour and style to this annual event. Our President, Mr David Taylor and some of the committee will be wearing the kilt, so if possible, join them. If you are not fortunate enough to own a highly prized kilt, male members of the family can wear a tartan tie or tam-o'-shanter and the females are encouraged to wear a tartan skirt. -

Twizel Highlights

FAIRLIE | LAKE TEKAPO | AORAKI / MOUNT COOK | TWIZEL HIGHLIGHTS FAIRLIE Explore local shops | Cafés KIMBELL Walking trails | Art gallery BURKES PASS Shopping & art | Heritage walk | Historic Church LAKE TEKAPO Iconic Church | Walks/trails LAKE PUKAKI Beautiful scenery | Lavender farm GLENTANNER Beautiful vistas | 18kms from Aoraki/Mount Cook Village AORAKI/MOUNT COOK Awe-inspiring mountain views | Adventure playground TWIZEL Quality shops | Eateries | Five lakes nearby | Cycling Welcome to the Mackenzie Region The Mackenzie Region spaces are surrounded by SUMMER provides many WINTER in the Mackenzie winter days are perfect is located at the heart snow-capped mountains, experiences interacting is unforgettable with for scenic flights and the p18 FAIRLIE of New Zealand’s South including New Zealand’s with the natural landscape uncrowded snow fields and nights crisp and clear for Island, 2.5 hour’s drive from tallest, Aoraki/Mount Cook, of our unique region, from unique outdoor experiences spectacular stargazing. Christchurch or 3 hours from with golden tussocks giving star gazing tours and scenic as well as plenty of ways p20 LAKE TEKAPO Be spoilt for choice Dunedin/Queenstown. way to turquoise-blue lakes, flights, to hot pools and to relax after a day on the with a wide variety of Explore one of the most fed by meltwater from cycle trails. Check out 4WD slopes. Ride the snow tube, accommodation styles, eat picturesque regions offering numerous glaciers. tours, farm tours and boating visit our family friendly snow local cuisine, and smile at p30 AORAKI/MOUNT COOK bright, sunny days and dark experiences or get your fields or relax in the hot pools. -

Designations

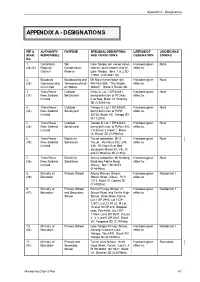

Appendix A - Designations APPENDIX A - DESIGNATIONS REF & AUTHORITY PURPOSE SITE/LEGAL DESCRIPTION LIFETIME OF UNDERLYING (MAP) RESPONSIBLE AND CONDITIONS DESIGNATION ZONING No. 1. Canterbury Soil Lake Tekapo soil conservation Has been given Rural (44/24) Regional Conservation reserve, south eastern end of effect to. Council Reserve Lake Tekapo. Secs 1 & 2 SO 11904 (145.8891 ha). 2. Broadcast Broadcasting and Mt Mary transmission site. Has been given Rural (28) Communicatio Telecommunicati Part Run 85A, “The Wolds effect to. ns Limited on Station Station”. Block X Pukaki SD. 3. Trans Power Outdoor Ohau A, Lot 1 DP 63831, Has been given Rural (37) New Zealand Switchyard being definition of Pt Ohau effect to. Limited river bed, Block VI, Strachey SD (0.9259 ha). 4. Trans Power Outdoor Tekapo A, Lot 1 DP 63830, Has been given Rural (44) New Zealand Switchyard being definition of Pt RS effect to. Limited 36738, Block XIII, Tekapo SD (0.1122ha). 5. Trans Power Outdoor Tekapo B, Lot 1 DP 63833, Has been given Rural (28) New Zealand Switchyard being definition of Pt Run 343 effect to. Limited (“Irishman’s Creek”). Block IX, Pukaki SD (0.5986ha). 6. Trans Power Electricity Twizel substation, SH 8 Has been given Rural (38) New Zealand Substation Twizel. Part Runs 292, 294, effect to. Limited 336. Pt Ohau River Bed situated in Blocks IV, VIII, XI and VI Strachey SD (2.5ha). 7. Trans Power Electricity Albury substation, Mt Nessing Has been given Rural (36) New Zealand Substation Road and Askins Road, effect to. Limited Albury. Sec 1 SO 9474 (0.4648ha). -

Fairlie Lake Tekapo Aoraki/Mt Cook Twizel Official Visitor Guide Shore of Lake Tekapo

fairlie lake tekapo aoraki/mt cook twizel Official Visitor Guide Shore of Lake Tekapo. Image credit: Johan Lolos Welcome to the Mackenzie Region The Mackenzie Region is situated at the heart of New Zealand’s South Island. It’s one of the most beautiful places in the country, with bright, sunny days and clear, starry nights. The land is sparsely populated (just over 4,000 people) and the amazing wide-open spaces are ringed by snow-capped mountains, including Aoraki Mount Cook, the tallest in New Zealand. Here, golden tussocks give way to remarkable turquoise-blue lakes, fed by meltwater from glaciers including the Tasman, the longest in New Zealand. This is the place to rediscover the magic of the night sky – the Mackenzie Region has been recognized as an International Dark Sky Reserve, the largest in the world and the only one in the Southern Hemisphere. The Mackenzie is the perfect place to experience your New Zealand outdoor adventure, or simply to take in the pure, breathtaking beauty of the landscape. Cover Image: Alps 2 Ocean Cycle Trail, Lake Pukaki share your 2 experience UPLOAD using #MackenzieNZ #CanterburyNZ area highlights Albury • Visit the rare collection of conifers at Anderson Arboretum. • Explore the quaint, scenic farming community. Fairlie • View the beautiful green fields and rolling hills from Mt Michael. P9 • Indulge in a great range of local eateries and shops. Kimbell • Visit the quirky art galleries. • Enjoy the Kimbell – Fairlie trail, on foot or by bike. Burkes Pass • Follow in the footsteps of early settlers on the Heritage Walk. • Visit a pioneer church, art gallery and unique shops. -

BODEN BLACK (A Novel)

BODEN BLACK (A Novel) and WITH AXE AND PEN IN THE NEW ZEALAND ALPS: DIFFERENCES BETWEEN OVERSEAS AND NEW ZEALAND WRITTEN ACCOUNTS OF CLIMBING MOUNT COOK 1882-1920 AND THE EMERGENCE OF A NEW ZEALAND VOICE IN MOUNTAINEERING LITERATURE BY JURA (LAURENCE) FEARNLEY A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2012 1 ABSTRACT This thesis has two components: creative and critical. The creative component is the novel Boden Black. It is a first person narrative, imagined as a memoir, and traces the life of its protagonist, Boden Black, from his childhood in the late 1930s to adulthood in the present day. The plot describes various significant encounters in the narrator’s life: from his introduction to the Mackenzie Basin and the Mount Cook region in the South Island of New Zealand, through to meetings with mountaineers and ‘lost’ family members. Throughout his journey from child to butcher to poet, Boden searches for ways to describe his response to the natural landscape. The critical study is titled With Axe and Pen in the New Zealand Alps. It examines the published writing of overseas and New Zealand mountaineers climbing at Aoraki/Mount Cook between 1882 and 1920. I advance the theory that there are stylistic differences between the writing of overseas and New Zealand mountaineers and that the beginning of a distinct New Zealand mountaineering voice can be traced back to the first accounts written by New Zealand mountaineers attempting to reach the summit of Aoraki/Mount Cook. -

Conservation and Biology of the Rediscovered Nationally Endangered Canterbury Knobbled Weevil, Hadramphus Tuberculatus

ISSN: 1177-6242 (Print) ISSN: 1179-7738 (Online) ISBN: 978-0-86476-397-6 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-86476-398-3 (Online) Lincoln University Wildlife Management Report No. 57 Conservation and biology of the rediscovered nationally endangered Canterbury knobbled weevil, Hadramphus tuberculatus Jenifer Iles1, Mike Bowie1, Peter Johns2 & Warren Chinn3 1Department of Ecology, Lincoln University PO Box 85084, Lincoln 7647, Canterbury. 2Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8013, Canterbury. 3Department of Conservation, 70 Moorhouse Ave, Addington, Christchurch 8011. Prepared for: Department of Conservation 2007 (Summer Scholarship Report) 2015 (Published) 2 Abstract Three areas near Burkes Pass Scenic Reserve were surveyed for the presence of Hadramphus tuberculatus, a recently rediscovered endangered weevil. The reserve itself was resurveyed to expand on a 2005/2006 survey. Non-lethal pitfall traps and mark and recapture methods were used. Six H. tuberculatus were caught in pitfall traps over 800 trap nights. Day and night searching of Aciphylla aurea was conducted. Four specimens were observed on Aciphylla flowers between 9 am and 1.30 pm within the reserve. No specimens were found outside of the reserve by either method. Other possible locations where H. tuberculatus may be found were identified and some visited. At most locations Aciphylla had already finished flowering, no H. tuberculatus were found. Presence of H. tuberculatus at other sites would be best determined by searching of Aciphylla flowers during the morning from late October onwards. 3 Introduction Hadramphus tuberculatus belongs to a small genus of large, nocturnal flightless weevils (Craw 1999). The protected fauna list in the Seventh Schedule of the Wildlife Amendment Act 1980, included Hadramphus tuberculatus (Craw 1999) and it was identified as one of the highest priorities for conservation action in Canterbury by Pawson and Emberson (2000). -

Conservation Management Strategy 2016 7

CMS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT STRATEGY Canterbury (Waitaha) 2016, Volume 1 CMS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT STRATEGY Canterbury (Waitaha) 2016, Volume 1 Cover image: Waimakariri River looking toward Shaler Range and Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o te Moana Photo: Graeme Kates September 2016, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 978-0-478-15091-9 (print) ISBN 978-0-478-15092-6 (online) Crown copyright © 2016 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to the Crown and abide by the other licence terms. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Please note that no departmental or governmental emblem, logo or Coat of Arms may be used in any way which infringes any provision of the Flags, Emblems, and Names Protection Act 1981. Attribution to the Crown should be in written form and not by reproduction of any such emblem, logo or Coat of Arms. Use the wording ‘Department of Conservation’ in your attribution, not the Department of Conservation logo. This publication is produced using paper sourced from well-managed, renewable and legally logged forests. Contents Foreword 7 Introduction 8 Purpose of conservation management strategies 8 Treaty partnership with Ngāi Tahu 9 CMS structure 10 Interpretation 11 CMS term 12 Relationship with other Department of Conservation strategic documents and tools 12 Relationship with other planning processes 14 Legislative tools 15 -

Historic Heritage of High-Country Pastoralism: South Island up to 1948 Historic Heritage of High-Country Pastoralism: South Island up to 1948

Historic heritage of high-country pastoralism: South Island up to 1948 Historic heritage of high-country pastoralism: South Island up to 1948 Roberta McIntyre Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand Note on place names: The place names mentioned in this publication are presented as they were reported in historical documents. Thus they are not necessarily the official place names as currently recognised by Land Information New Zealand. Cover: Aerial oblique of Lake Guyon, which is a part of St James Station, one of the Amuri runs. View to the northwest. The homestead area is the open patch on the north side of the lake (see Fig. 8). Note pattern of repeatedly fired beech forest now reverting to bracken. Photo: Kevin L. Jones, Department of Conservation. Individual copies of this book are printed, and it is also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright July 2007, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 978–0–478–14233–4 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14234–1 (web PDF) This text was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Sue Hallas and layout by Amanda Todd. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. ContEnts Preface 7 Abstract 9 1. Introduction 10 2. -

Fairlie | Takapō/Lake Tekapo | Aoraki/Mount Cook | Twizel

FAIRLIE | TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO | AORAKI/MOUNT COOK | TWIZEL Stargazing at Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park Photo by: WeDreamofTravel.com Lake Pukaki - Rachel Gillespie HIGHLIGHTS FAIRLIE Explore local shops | Cafés KIMBELL Walking trails | Art gallery BURKES PASS Shopping & art | Heritage walk | Historic church TAKAPO¯ /LAKE TEKAPO Iconic church | Walks/trails LAKE PUKAKI Beautiful scenery | Lavender farm GLENTANNER Beautiful vistas | 18km from Aoraki/Mount Cook Village AORAKI/MOUNT COOK Awe-inspiring mountain views | Adventure playground TWIZEL Quality shops | Eateries | Five lakes nearby | Cycling Clearest starry skies, highest mountains, vivid turquoise lakes, expansive golden grasslands – welcome to the Mackenzie Region. Home to Aoraki/Mount Stay in boutique Many of the photos in this Cook & Takapo¯/Lake accommodation, eat local p14 FAIRLIE guide are from Rachel Tekapo, this region is one cuisine, and smile at the Gillespie, a Twizel-based of the most photographed genuine Kiwi hospitality you’ll professional photographer. TAKAPO¯ / and visited in all of New find all around you. This is p16 Rachel and her team offer Zealand. Take a scenic a landscape that stays in LAKE TEKAPO guided walking, stargazing flight into the mountains your memory forever - truly and photography workshops and land on glaciers; enjoy one of New Zealand’s most AORAKI / throughout the entire p 23 stargazing within the Aoraki cherished treasures. Come MT COOK Mackenzie Region. Mackenzie International discover the Mackenzie! www.nztraveladventure.com Dark Sky Reserve; -

The New Zealand Azette

Issue No. 101 • 2141 The New Zealand azette WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 21 JUNE 1990 Contents Government Notices 2142 Authorities and Other Agencies of State Notices 2148 Land Notices 2149 Regulation Summary 2154 General Section .. 2155 Using the Gazette The New Zealand Gazette, the official newspaper of the Closing time for lodgment of notices at the Gazette Office: Government of New Zealand, is published weekly on 12 noon on Tuesdays prior to publication (except for holiday Thursdays. Publishing time is 4 p.m. periods when special advice of earlier closing times will be Notices for publication and related correspondence should be given). addressed to: Notices are accepted for publi cation in the next available issue, Gazette Office, unless otherwise specified. Department of Internal Affairs, P.O. Box 805, Notices being submitted for publication must be a reproduced Wellington. copy of the original. Dates, proper names and signatures are Telephone (04) 738 699 to be shown clearly. A covering instruction setting out require Facsimile (04) 499 1865 ments must accompany all notices. or lodged at the Gazette Office, Seventh Floor, Dalmuir Copy will be returned unpublished if not submitted in House, 114 The Terrace, Wellington. accordance with these requirements. 2142 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 101 Availability Government Buildings, 1 George Street, Palmerston North. The New Zealand Gazette is available on subscription from the Government Printing Office Publications Division or over the Cargill House, 123 Princes Street, Dunedin. counter from Government Bookshops at: Housing Corporation Building, 25 Rutland Street, Auckland. Other issues of the Gazette: 33 Kings Street, Frankton, Hamilton. Commercial Edition-published weekly on Wednesdays. -

Evidence of Mandy Waaka-Home on Behalf of Te Rūnanga O Ngāi Tahu and Te Rūnanga O Arowhenua

BEFORE THE ENVIRONMENT COURT ENV-2009-CHC-175, 181,183,184, 187, 190,191,192, 193 IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER appeals pursuant to clause 14 of Schedule 1 to the Act BETWEEN HIGH COUNTRY ROSEHIP ORCHARDS LIMITED AND MACKENZIE LIFESTYLE LIMITED and others Appellant AND MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL Respondent EVIDENCE OF MANDY WAAKA-HOME ON BEHALF OF TE RŪNANGA O NGĀI TAHU AND TE RŪNANGA O AROWHENUA Cultural Issues 9 September 2016 Barristers & Solicitors Simpson Grierson J G A Winchester Telephone: +64-4-924 3503 Facsimile: +64-4-472 6986 Email: [email protected] DX SX11174 PO Box 2402 SOLICITORS WELLINGTON 6140 28362247_1.docx TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. MIHIMIHI – INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 2. QUALIFICATIONS AND EXPERIENCE ......................................................................... 1 3. SCOPE OF EVIDENCE ................................................................................................... 5 4. SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE ............................................................................................. 5 5. KAITIAKI PAPATIPU RŪNANGA ................................................................................... 6 6. NGAI TAHU RELATIONSHIP WITH TE MANAHUNA ................................................... 6 7. MAHIKA KAI – GATHERING OF FOODS AND RESOURCES ..................................... 7 8. ARA TAWHITO – THE ANCIENT PATHWAYS ............................................................