BODEN BLACK (A Novel)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qt7vk4k1r0 Nosplash 9Eebe15

Fiction Beyond Secularism 8flashpoints The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) 1. On Pain of Speech: Fantasies of the First Order and the Literary Rant, Dina Al-Kassim 2. Moses and Multiculturalism, Barbara Johnson, with a foreword by Barbara Rietveld 3. The Cosmic Time of Empire: Modern Britain and World Literature, Adam Barrows 4. Poetry in Pieces: César Vallejo and Lyric Modernity, Michelle Clayton 5. Disarming Words: Empire and the Seductions of Translation in Egypt, Shaden M. -

Net Proceeds

word Net Proceeds Committee Decisions Approved applications 2,879,060.69 1 August 2019 to 31 July 2020 Partially approved applications 1,069,887.89 Total Approved 3,948,948.58 Total Declined applications 2,578,741.32 Total donations returned $190,852.68 Approved Applications 2,879,060.69 App No. Organisation name Category Requested amount ($) Compliant Amount ($) Approved amount ($) Approval date Declined Amount Application status Declined reasons MF22117 Adventure Specialties Trust Community 610.08 557.04 557.00 22/10/2019 Approved MF22494 Age Concern New Zealand Palmerston North & Districts Branch Incorporated Social Services 3,420.00 2,973.92 2,973.00 10/03/2020 Approved MF22029 Aphasia New Zealand (AphasiaNZ) Charitable Trust Community 2,000.00 2,000.00 2,000.00 25/09/2019 Approved MF21929 Arohanui Hospice Service Trust Social Services 7,200.00 7,087.00 7,087.00 28/08/2019 Approved MF22128 Ashhurst School Educational or Training Organisations 3,444.00 3,444.00 3,444.00 22/10/2019 Approved MF22770 Athletic College Old Boys Cricket Club Incorporated Amateur Sport 5,000.00 5,000.00 5,000.00 30/07/2020 Approved MF22129 Athletic College Old Boys Cricket Club Incorporated Amateur Sport 3,254.94 3,254.94 3,254.00 3/12/2019 Approved MF22768 Athletic College Old Boys Cricket Club Incorporated Amateur Sport 1,337.80 1,337.80 1,337.00 30/07/2020 Approved MF21872 Athletic College Old Boys Cricket Club Incorporated Amateur Sport 5,518.00 5,518.00 5,518.00 28/08/2019 Approved MF22725 Athletic College Old Boys Cricket Club Incorporated Amateur Sport -

Submission Form .. , Draft Aoraki/Mount Cook National

Submission Form DraftAoraki/Mount Cook National Park Management Plan Once you have completed this form Send by post to: Aoraki/Mount Cook NPMP Submissions, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 4715, Christchurch Mail Centre, Christchurch 8140 or email to: [email protected] Submissions must be received no later than 4.00 pm, Monday 4th February 2019 Anyone may make a submission, either as an individual or on behalf of an organisation. Please ensure all sections of this form are completed. You may either use this form or prepare your own but if preparing your own please use the same headings as used in this form. A Word version of this form is available on the Department's website: www.doc.govt.nz/aoraki-mt-cook-plan-review Submitter details: Paul Agnew Name of submitter or contact person: Organisation name: (if on behalf of an organisation) Postal address: lnvercargill Telephone number: (the best number to contact you on) Erl: 0 I wish to be heard in support of my submission (this means you can speak at a hearing) D I do not wish to be heard in support of my submission (tick one box) Signature: Your submission is submitted as part of a public process and once received by the Department it is subject to the provisions of the Privacy Act 1993 and the Official Information Act 1981. The Department may post your submission on its website and also make it available to departmental staff, any consultant used, the relevant Conservation Board and the New Zealand Conservation Authority. Your submission may be made available to any member of the public following a request made under the Official Information Act 1981. -

Queer Trans-Tasman Mobility, Then and Now

Brickell, C., Gorman-Murray, A. and de Jong, A. (2018) Queer trans-Tasman mobility, then and now. Australian Geographer, 49(1), pp. 167-184. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/212471/ Deposited on: 31 March 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Queer Trans-Tasman Mobility, Then and Now Final manuscript version: Gorman-Murray, A., Brickell, C., de Jong, A. (2017), Australian Geographer. Abstract This article situates queer mobility within wider historical geographies of trans- Tasman flows of goods, people and ideas. Using case studies of women’s and men’s experiences during the early twentieth century and the twenty-first century, it shows that same-sex desire is a constituent part of these flows and, conversely, Antipodean mobility has fostered particular forms of desire, sexual identity, and queer community and politics. Particular landscapes, rural and urban, in both New Zealand and Australia, have shaped queer desire in a range of diverging and converging ways. Shifting political, legal and social landscapes across New Zealand and Australia have wrought changes in trans-Tasman travel over time. This investigation into the circuits of queer trans-Tasman mobility both underscores and urges wider examinations of the significance of trans-Tasman crossings in queer lives, both historically and in contemporary society. Key words: New Zealand; Australia; trans-Tasman mobility; queer travel; LGBT; queer politics 1 Queer Trans-Tasman Mobility, Then and Now Circuits, sexuality and space Australia and New Zealand have a long-established inter-relationship, denoted as ‘trans-Tasman relations’. -

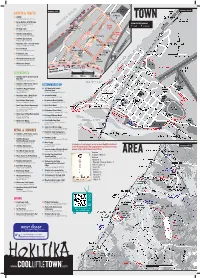

Hokitika Maps

St Mary’s Numbers 32-44 Numbers 1-31 Playground School Oxidation Artists & Crafts Ponds St Mary’s 22 Giſt NZ Public Dumping STAFFORD ST Station 23 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 7448 TOWN Oxidation To Kumara & 2 1 Ponds 48 Gorge Gallery at MZ Design BEACH ST 3 Greymouth 1301 Kaniere Kowhitirangi Rd. TOWN CENTRE PARKING Hokitika Beach Walk Walker (03) 755 7800 Public Dumping PH: HOKITIKA BEACH BEACH ACCESS 4 Health P120 P All Day Park Centre Station 11 Heritage Jade To Kumara & Driſt wood TANCRED ST 86 Revell St. PH: (03) 755 6514 REVELL ST Greymouth Sign 5 Medical 19 Hokitika Craſt Gallery 6 Walker N 25 Tancred St. (03) 755 8802 10 7 Centre PH: 8 11 13 Pioneer Statue Park 6 24 SEWELL ST 13 Hokitika Glass Studio 12 14 WELD ST 16 15 25 Police 9 Weld St. PH: (03) 755 7775 17 Post18 Offi ce Westland District Railway Line 21 Mountain Jade - Tancred Street 9 19 20 Council W E 30 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8009 22 21 Town Clock 30 SEAVIEW HILL ROAD N 23 26TASMAN SEA 32 16 The Gold Room 28 30 33 HAMILTON ST 27 29 6 37 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8362 CAMPCarnegie ST Building Swimming Glow-worm FITZHERBERT ST RICHARDS DR kiosk S Pool Dell 31 Traditional Jade Library 34 Historic Lighthouse 2 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 5233 Railway Line BEACH ST REVELL ST 24hr 0 250 m 500 m 20 Westland Greenstone Ltd 31 Seddon SPENCER ST W E 34 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8713 6 1864 WHARF ST Memorial SEAVIEW HILL ROAD Monument GIBSON QUAY Hokitika 18 Wilderness Gallery Custom House Cemetery 29 Tancred St. -

Ïg8g - 1Gg0 ISSN 0113-2S04

MAF $outtr lsland *nanga spawning sur\feys, ïg8g - 1gg0 ISSN 0113-2s04 New Zealand tr'reshwater Fisheries Report No. 133 South Island inanga spawning surv€ys, 1988 - 1990 by M.J. Taylor A.R. Buckland* G.R. Kelly * Department of Conservation hivate Bag Hokitika Report to: Department of Conservation Freshwater Fisheries Centre MAF Fisheries Christchurch Servicing freshwater fisheries and aquaculture March L992 NEW ZEALAND F'RESTTWATER F'ISHERIES RBPORTS This report is one of a series issued by the Freshwater Fisheries Centre, MAF Fisheries. The series is issued under the following criteria: (1) Copies are issued free only to organisations which have commissioned the investigation reported on. They will be issued to other organisations on request. A schedule of reports and their costs is available from the librarian. (2) Organisations may apply to the librarian to be put on the mailing list to receive all reports as they are published. An invoice will be sent for each new publication. ., rsBN o-417-O8ffi4-7 Edited by: S.F. Davis The studies documented in this report have been funded by the Department of Conservation. MINISTBY OF AGRICULTUBE AND FISHERIES TE MANAlU AHUWHENUA AHUMOANA MAF Fisheries is the fisheries business group of the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The name MAF Fisheries was formalised on I November 1989 and replaces MAFFish, which was established on 1 April 1987. It combines the functions of the t-ormer Fisheries Research and Fisheries Management Divisions, and the fisheries functions of the former Economics Division. T\e New Zealand Freshwater Fisheries Report series continues the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Fisheries Environmental Report series. -

Natural Landscapes and Gardens of New Zealand's South Island

Natural Landscapes and Gardens of New Zealand’s South Island – November 2021 5 NOV – 21 NOV 2021 Code: 22166 Tour Leaders Stephen Ryan, Craig Lidgerwood Physical Ratings Horticulturalist Stephen Ryan visits an extraordinary variety of private gardens and natural landscapes including Milford Sound, The Catlins and the spectacular Mackenzie Region. Overview Led by horticulturalist Stephen Ryan this tour visits an extraordinary variety of public and private gardens and spectacular natural landscapes of New Zealand's South Island. Stephen will be assisted by Craig Lidgerwood. Explore the beautiful Malborough Region, famous for its traditional gardens and viticulture. Enjoy the hospitality of the garden owners at the MacFarlane’s magical Winterhome garden, Huguette Michel’s Hortensia and Carolyn Ferraby’s Barewood Gardens. Visit 5 gardens classified as Gardens of International Significance: Sir Miles Warren's private garden, Ohinetahi (Christchurch), Flaxmere Garden (North Canterbury), Trotts Garden (Ashburton), Larnach Castle Gardens (Dunedin) and the Dunedin Botanic Garden. By special appointment view Broadfields NZ Landscape Garden designed by Robert Watson in Christchurch, Maple Glen Gardens in Eastern Southland, and the spectacular gardens of Clachanburn Station in Central Otago. Travel the rugged west coast and visit Fox Glacier and Mount Cook on the journey south through Westland National Park. Spend 2 nights at the Lake Moeraki Wildnerness Lodge, in the heart of Te Wahipounamu World Heritage Area where local experts. will take you though the rainforest into the habitats of glow- worms, Morepork Owls, fur seals and Fiordland Crested Penguins. Travel through the Fiordland National Park encompassing mountain, lake, fiord and rainforest environments. Enjoy a relaxing cruise of Milford Sound, described by Rudyard Kipling as the '8th wonder of the world'. -

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper for West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper For West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board TITLE OF PAPER STATUS REPORT AUTHOR: Mark Davies SUBJECT: Status Report for the Board for period ending 15 April 2016 DATE: 21 April 2016 SUMMARY: This report provides information on activities throughout the West Coast since the 19 February 2016 meeting of the West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board. MARINE PLACE The Operational Plan for the West Coast Marine Reserves is progressing well. The document will be sent out for Iwi comment on during May. MONITORING The local West Coast monitoring team completed possum monitoring in the Hope and Stafford valleys. The Hope and Stafford valleys are one of the last places possums reached in New Zealand, arriving in the 1990’s. The Hope valley is treated regularly with aerial 1080, the Stafford is not treated. The aim is to keep possum numbers below 5% RTC in the Hope valley and the current monitor found an RTC of 1.3% +/- 1.2%. The Stafford valley is also measured as a non-treatment pair for the Hope valley, it had an RTC of 21.5% +/- 6.2%. Stands of dead tree fuchsia were noted in the Stafford valley, and few mistletoe were spotted. In comparison, the Hope Valley has abundant mistletoe and healthy stands of fuchsia. Mistletoe recruitment plots, FBI and 20x20m plots were measured in the Hope this year, and will be measured in the Stafford valley next year. KARAMEA PLACE Planning Resource Consents received, Regional and District Plans, Management Planning One resource consent was received for in-stream drainage works. -

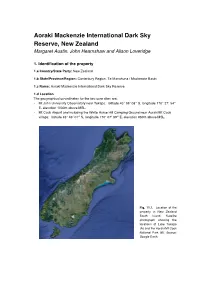

TS2-V6.0 11-Aoraki

Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve, New Zealand Margaret Austin, John Hearnshaw and Alison Loveridge 1. Identification of the property 1.a Country/State Party: New Zealand 1.b State/Province/Region: Canterbury Region, Te Manahuna / Mackenzie Basin 1.c Name: Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 1.d Location The geographical co-ordinates for the two core sites are: • Mt John University Observatory near Tekapo: latitude 43° 59′ 08″ S, longitude 170° 27′ 54″ E, elevation 1030m above MSL. • Mt Cook Airport and including the White Horse Hill Camping Ground near Aoraki/Mt Cook village: latitude 43° 46′ 01″ S, longitude 170° 07′ 59″ E, elevation 650m above MSL. Fig. 11.1. Location of the property in New Zealand South Island. Satellite photograph showing the locations of Lake Tekapo (A) and the Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park (B). Source: Google Earth 232 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.e Maps and Plans See Figs. 11.2, 11.3 and 11.4. Fig. 11.2. Topographic map showing the primary core boundary defined by the 800m contour line Fig. 11.3. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boun- daries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 233 Fig. 11.4. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boundaries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary 234 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.f Area of the property Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve is located in the centre of the South Island of New Zealand, in the Canterbury Region, in the place known as Te Manahuna or the Mackenzie Basin (see Fig. -

New Writing EDITED by THOM CONROY

Intelligent, relevant books for intelligent, inquiring readers Home New writing EDITED BY THOM CONROY FINE ESSAYS FROM TWENTY-TWO OF NEW ZEALAND’S BEST WRITERS A compendium of non-fiction pieces held together by the theme of ‘Home’ and commissioned from 22 of New Zealand’s best writers. Strong, relevant, topical and pertinent, these essays are also compelling, provocative and affecting, they carry the reader from Dunedin to West Papua, Jamaica to Grey’s Avenue, Auckland. In this marvellous collection Selina Tusitala Marsh, Martin Edmond, Ashleigh Young, Lloyd Jones, Laurence Fearnley, Sue Wootton, Elizabeth Knox, Nick Allen, Brian Turner, Tina Makereti, Bonnie Etherington, Paula Morris, Thom Conroy, Jill Sullivan, Sarah Jane Barnett, Ingrid Horrocks, Nidar Gailani, Helen Lehndorf, James George and Ian Wedde show that the art of the essay is alive and well. ‘ . this collection is exceptionally good . fun to read, relevant, compassionate and frequently sharp’ — Annaleese Jochems, Booksellers NZ Blog $39.99 ‘[The essays] are honest, moving and thoughtful, various in style and content, all a delight to read. To contemplate what ‘home’ means to us in a physical, emotional and CATEGORY: Literature philosophical sense, Home: New Writing is a marker of social and cultural history as well ISBN: 978-0-9941407-5-3 as of politics, on the grand and small scale.’ — Stella Chrysostomou, VOLUME; Manawatu eSBN: 978-0-9941407-6-0 Standard 29 June 2017 BIC: DNF, IMBN BISAC: LCO10000 ABOUT THE EDITOR PUBLISHER: Massey University Press IMPRINT: Massey University Press Dr Thom Conroy teaches creative writing in the School of English and Media Studies at PUBLISHED: July 2017 Massey University. -

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award

Our Finest Illustrated Non-Fiction Award Crafting Aotearoa: Protest Tautohetohe: A Cultural History of Making Objects of Resistance, The New Zealand Book Awards Trust has immense in New Zealand and the Persistence and Defiance pleasure in presenting the 16 finalists in the 2020 Wider Moana Oceania Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams, Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the country’s Puawai Cairns Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai, Published by Te Papa Press most prestigious awards for literature. Damian Skinner Published by Te Papa Press Bringing together a variety of protest matter of national significance, both celebrated and Challenging the traditional categorisations The Trust is so grateful to the organisations that continue to share our previously disregarded, this ambitious book of art and craft, this significant book traverses builds a substantial history of protest and belief in the importance of literature to the cultural fabric of our society. the history of making in Aotearoa New Zealand activism within Aotearoa New Zealand. from an inclusive vantage. Māori, Pākehā and Creative New Zealand remains our stalwart cornerstone funder, and The design itself is rebellious in nature Moana Oceania knowledge and practices are and masterfully brings objects, song lyrics we salute the vision and passion of our naming rights sponsor, Ockham presented together, and artworks to Residential. This year we are delighted to reveal the donor behind the acknowledging the the centre of our influences, similarities enormously generous fiction prize as Jann Medlicott, and we treasure attention. Well and divergences of written, and with our ongoing relationships with the Acorn Foundation, Mary and Peter each. -

Wilderness Lodge Route Guide

Wilderness Lodge® Arthur’s Pass 16km East of Arthur’s Pass Village, Highway 73 [email protected] Wilderness Lodges +64 3318 9246 of New Zealand Wilderness Lodge® Lake Moeraki 90km South of Fox Glacier, Highway 6 wildernesslodge.co.nz [email protected] +64 3750 0881 Route Guide: Lake Moeraki to Arthur’s Pass This journey of 360km (about 200 miles) involves 5 to 6 hours of driving with great scenery and interesting stops along the way. We recom- mend that you allow as much time as possible. Key features include: beautiful rainforest; six large forested lakes; glistening snowy mountains and wild glacier rivers; the famous Fox and Franz Josef glaciers; the goldfields town of Hokitika; ascending Arthur’s Pass through the dramatic cleft of the Otira Gorge; and glorious alpine herbfields and shrublands at the summit. The times given below are driving times only. Enjoy Your Journey, Drive Safely & Remember to Keep Left Wilderness Lodge Lake Moeraki to Fox Glacier (92kms – 1¼ hrs) An easy drive through avenues of tall forest and lush farmland on mainly straight flat roads. Key features along this leg of the journey include Lake Paringa (20km), the Paringa River café and salmon farm (32km), a brief return to the coast at Bruce Bay (44km), and the crossing of three turbulent glacier rivers – the Karangarua (66km), Cook (86km) and Fox (90km) – at the point where they break free from the confines of their mountain valleys. In fair weather, striking views are available of the Sierra Range from the Karangarua River bridge (66km), Mt La Perouse (3079m) from the bridge across the Cook River (88km)and Mt Tasman (3498m) from the bridge over the Fox River (91km).The long summit ridge of Mt Cook (3754) is also briefly visible from just south of the Ohinetamatea River (15km north of the Karangarua River ) and again 4km further north on the approach to Bullock Creek.