C:\Lower Churchill Files\March 20\U-72.Htm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson Strait-Ungava Bay Common Eider Surveys

Hudson Strait Common Eider and Polar Bear Surveys 2014 Field Season Report Project Overview Our ongoing research investigates the status of common eiders, red-throated loons and other ground nesting birds nesting on coastal islands in the Hudson Strait, Ungava Bay, and Foxe Basin marine regions of the eastern Canadian Arctic. There is considerable interest in the north relating to issues of human health and food security, as well as wildlife conservation and sustainable harvest. We are focusing on several emerging issues of significant ecological and conservation importance: 1. Quantifying the extent of polar bear predation on eider nests as sea ice diminishes. 2. Quantifying the spread and severity of avian cholera outbreaks among northern eider populations. 3. Quantifying the distribution and abundance of birds nesting on coastal islands in support of environmental sensitivity mapping and marine emergency response planning. Clockwise from top left: Adamie Mangiuk conducting surveys in Digges Sound, Nik Clyde measuring ponds on an eider colony, a Common Eider on her nest. 2014 Research Highlights Avian Cholera and Marine Birds Avian cholera is one of the most lethal diseases for birds in North America. Although it has circulated in southern Canada and the United States for many years, its emergence among eiders in the north is new. To better understand transmission dynamics and potential population level impacts for eiders we have undertaken sampling across the eastern Arctic. We are examining the geographic extent of the outbreaks, as well as the origins, virulence and evolution of the disease. Map of survey locations and the year in which they were completed. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

Lincoln Sea Hall Basin MARINE ATLAS ARCTIC CANADA’S GREENLAND Ellesmere Island Kane Basin Nares Strait N nd ansen Sou s d Axel n Sve Heiberg rdr a up Island l Ch ann North CANADA’S s el I Pea Water ry Ch a h nnel Massey t Sou Baffin e Amund nd ISR Boundary b Ringnes Bay Ellef Norwegian Coburg Island Grise Fiord a Ringnes Bay Island ARCTIC MARINE z Island EEZ Boundary Prince i Borden ARCTIC l Island Gustaf E Adolf Sea Maclea Jones n Str OCEAN n ait Sound ATLANTIC e Mackenzie Pe Ball nn antyn King Island y S e trait e S u trait it Devon Wel ATLAS Stra OCEAN Q Prince l Island Clyde River Queens in Bylot Patrick Hazen Byam gt Channel o Island Martin n Island Ch tr. Channel an Pond Inlet S Bathurst nel Qikiqtarjuaq liam A Island Eclipse ust Lancaster Sound in Cornwallis Sound Hecla Ch Fitzwil Island and an Griper nel ait Bay r Resolute t Melville Barrow Strait Arctic Bay S et P l Island r i Kel l n e c n e n Somerset Pangnirtung EEZ Boundary a R M'Clure Strait h Island e C g Baffin Island Brodeur y e r r n Peninsula t a P I Cumberland n Peel Sound l e Sound Viscount Stefansson t Melville Island Sound Prince Labrador of Wales Igloolik Prince Sea it Island Charles ra Hadley Bay Banks St s Island le a Island W Hall Beach f Beaufort o M'Clintock Gulf of Iqaluit e c n Frobisher Bay i Channel Resolution r Boothia Boothia Sea P Island Sachs Franklin Peninsula Committee Foxe Harbour Strait Bay Melville Peninsula Basin Kimmirut Taloyoak N UNAT Minto Inlet Victoria SIA VUT Makkovik Ulukhaktok Kugaaruk Foxe Island Hopedale Liverpool Amundsen Victoria King -

30160105.Pdf

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2009/008 Document de recherche 2009/008 An Ecological and Oceanographical Évaluation écologique et Assessment of the Alternate Ballast océanographique de la zone Water Exchange Zone in the Hudson alternative pour l’échange des eaux Strait Region de ballast de la région du détroit d'Hudson D.B. Stewart and K.L. Howland Fisheries and Oceans Canada Central and Arctic Region, Freshwater Institute 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est -

C. C. I. W. Library

vv~• ,,. ........ '-./ \. \ \niti&l ..... , ~ ~ ~ .Fi.\e_ .......-········ C. C. I. W. LIBRARY MANUSCRIPT No. REPORT SERIES 4 ~ {3tJ.~t-t~tt4eetttJ.~t- ttJ. t~e Oee4~t-tJ.fJ't4ft~'f tJ.I ~eedd-tJ.~t- ~a~~ F. G . BARBER Morine Sciences Branch 1967 Deportment of c[nergy, Mines and Resources, Ottowa . A CONTRIBUTION TO THE OCEANOGRAPHY OF HUDSON BAY F. G. Barber \ I I 1967 .. ROGER DUHAMEL, F.R.S.C. QUEEN'S PRINTER AND CONTROLLER OF STATIONERY OTTAWA, 1967 , • CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION •......•.....••.••...•.•••.... , . • . • . 1 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF PROPERTIES 4 FACTORS WHICH DETERMINE THE DISTRIBUTIONS 20 \ 3. ................ 3. 1 Net current and depth • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 20 3. 2 Tidal streams and tidal mixing. • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . 23 3. 3 Exchange of energy at the surface ••• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • 26 3. 4 Ice cover and the surface mixed layer • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • .. • • • • 2 7 3. 5 Fresh water from run-off . 28 3. 6 Sllrface wind . .. 31 4. DISCUSSION . • . • . • . • . • . 32 4.1 A fresh water budget ................................ -..... 32 4.2 A volume budget ...•........................•....•........ 36 4.3 The probable near-surface salinity distribution in winter •••••• 38 4.4 The influence of ice cover in the 1961 season ••••••••..•..... 40 4.5 A preliminary heat budget of the sea in the vicinity of Churchill for 19 61 . 45 4.51 Short-wave radiation from sun and sky •••••••••••• 47 4.52 Reflected short-wave radiation •••••••.•.•.•••.•• 47 4.53 Effective long-wave back radiation .•.••••••.•..•. 48 4.54 Evaporation . .................................. 48 4.55 Conduction of sensible heat 49 4.56 Precipitation ............ ~ .................... 50 4.57 Net of the radiative and flux terms •••.••.••••.••• 50 4.58 Heat storage and advection ••••••••••••..•••••••. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

CANADA’S ARCTIC MARINE ATLAS This Atlas is funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. I | Suggested Citation: Oceans North Conservation Society, World Wildlife Fund Canada, and Ducks Unlimited Canada. (2018). Canada’s Arctic Marine Atlas. Ottawa, Ontario: Oceans North Conservation Society. Cover image: Shaded Relief Map of Canada’s Arctic by Jeremy Davies Inside cover: Topographic relief of the Canadian Arctic This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. All photographs © by the photographers ISBN: 978-1-7752749-0-2 (print version) ISBN: 978-1-7752749-1-9 (digital version) Library and Archives Canada Printed in Canada, February 2018 100% Carbon Neutral Print by Hemlock Printers © 1986 Panda symbol WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (also known as World Wildlife Fund). ® “WWF” is a WWF Registered Trademark. ARCTIC BIRDS SIMPLIFIED FOOD WEB COASTAL AND MARINE BIRDS OF THE ARCTIC GEESE LOONS SEABIRDS SEA DUCKS fish Ecological significance ing tradition by both Indigenous peoples and European Coastal plain flora COASTAL & MARINE carrion Marine birds are found around the globe, from the poles settlers. These days, most marine bird species are pro- BIRDS insect to the tropics, where they live at the interface between tected from harvest by non-Indigenous hunters across Coastal saltmarsh flora fish - Geese air, land, sea, and ice. The harsh conditions that marine Canada, except for a few waterfowl species (eiders, fish - Sea Ducks birds find in these environments have caused unique scoters) and murres specifically in Newfoundland and Intertidal zone flora insect SHOREBIRDS - Loons adaptations in their physiology and morphology and Labrador. -

THE HUDSON BAY, JAMES BAY and FOXE BASIN MARINE ECOSYSTEM: a Review

THE HUDSON BAY, JAMES BAY AND FOXE BASIN MARINE ECOSYSTEM: A Review Agata Durkalec and Kaitlin Breton Honeyman, Eds. Polynya Consulting Group Prepared for Oceans North June, 2021 The Hudson Bay, James Bay and Foxe Basin Marine Ecosystem: A Review Prepared for Oceans North by Polynya Consulting Group Editors: Agata Durkalec, Kaitlin Breton Honeyman, Jennie Knopp and Maude Durand Chapter authors: Chapter 1: Editorial team Chapter 2: Agata Durkalec, Hilary Warne Chapter 3: Kaitlin Wilson, Agata Durkalec Chapter 4: Charity Justrabo, Agata Durkalec, Hilary Warne Chapter 5: Agata Durkalec, Hilary Warne Chapter 6: Agata Durkalec, Kaitlin Wilson, Kaitlin Breton-Honeyman, Hilary Warne Cover photo: Umiujaq, Nunavik (photo credit Agata Durkalec) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Approach ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 GEOGRAPHICAL BOUNDARIES ........................................................................................................................... -

Atlas Marin De L'arctique Canadien

ATLAS MARIN DE L’ARCTIQUE CANADIEN ATLAS MARIN DE L’ARCTIQUE CANADIEN Citation suggérée : Oceans North Conservation Society, Fonds mondial pour la nature Canada et Canards Illimités Canada. (2018). Atlas marin de l’Arctique canadien. Ottawa, Ontario : Oceans North Conservation Society. Image de couverture : Carte topographique au relief par ombres portées de l’Arctique canadien par Jeremy Davies Couverture intérieure : Topographie de l’Arctique canadien Ce travail tombe sous la licence Creative Commons Attribution – Utilisation non commerciale 4.0 International. Pour voir une copie de cette licence, consultez https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode.fr ou envoyez une lettre à Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, États-Unis. Toutes les photographies sont la propriété exclusive des photographes. Cet atlas est financé en partie par ISBN : 978-1-7752749-0-2 (version imprimée) la Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. ISBN : 978-1-7752749-1-9 (version numérique) Bibliothèque et Archives Canada MIXTE Papier provenant Imprimé au Canada en février 2018 de sources responsables Impression 100 % neutre en carbone par Hemlock Printers © 1986 Symbole du Panda WWF – Fonds mondial pour la nature. ® « WWF » est une marque déposée de WWF (Fonds mondial pour la nature). I | TABLE DES MATIÈRES Avant-propos .................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................... iv Carte de référence de l’Arctique canadien .................. 2 -

Digges Island Seabird Research Station

Digges Island Seabird Research Station A small cabin sleeps 5 people and provides a small space for office work. Canvas tents are used for kitchen facilities and storage. Freshwater collected from a nearby stream is used for cooking and drinking. View of Digges Island cabin and kitchen and storage tents. Photo credit: Mike Janssen, Environment Canada Name Email Phone Number Primary Contact Amie Black [email protected] (613) 998-8523 Secondary Contact Grant Gilchrist [email protected] (613) 998-7364 Owner Environment and Climate Change Canada Membership Regular Member Website www.ec.gc.ca Latitude 62.533333 Longitude -77.75 Location Off Northern Nunavik Nearest Community Ivujivik Territory/ Province Nunavut Aboriginal Government/ Homeland Nunavik Marine Region Facility Type Seasonally-Operated Field Camp Research Hinterland Coastal, Marine, Sea Ice Main Research Disciplines Environmental Sciences, Marine Biology Research History Environment Canada has been engaged in monitoring Thick-billed Murre populations in Hudson Strait since the early 1950Ís and has regularly monitored the colonies in Digges Sound since the early 1980's. Current Projects Environment Canada is working to determine the distribution and abundance patterns of Thick-billed Murres, to identify their use of key marine habitats in Digges Sound Power Generator Communications Satellite phone, VHF Local Transportation By local boat from Ivujivik, Quebec (25 km) Equipment Storage N/A Dormitory/Sleeping Facilities A small cabin sleeps 5 people Dining/Kitchen Facilities A canvas tent is used to house kitchen facilities. Laboratory Facilities N/A Fuel Availability N/A Research Requirements Migratory Bird Permit Nunavut Research Permit Land-use permit Special Rules and Regulations N/A Local External Resources N/A Nearest Medical Service Ivujivik (25km) Safety Considerations Environment Canada health and safety guidelines must be followed at this site. -

Habitats Marins Clés Pour Les Oiseaux Migrateurs Au Nunavut Et Dans Les Territoires Du Nord-Ouest

Mark L. Mallory Alain J. Fontaine Habitats marins clés pour les oiseaux migrateurs au Nunavut et dans les Territoires du Nord-Ouest Publication hors série Numéro 109 Service canadien de la faune Envi ronnement Environment Canada Canada Service canadien Canadian Wildlife de la faune Service Service canadien de la faune Publications hors série Les Publications hors série font état des résultats de recherches originales effectuées par les membres du personnel du Service canadien de la faune ou appuyées par le Service. Ces publications ont fait l’objet d’un examen par des pairs. Conseil d’édition Le Service canadien de la faune C.D. Ankney Le Service canadien de la faune d’Environnement University of Western Ontario Canada est chargé des questions de compétence fédérale touchant les espèces sauvages, notamment de protéger et de David Cairns gérer les oiseaux migrateurs et les habitats canadiens Pêches et Océans Canada d’importance nationale. Il est aussi responsable des espèces en péril, de la réglementation du commerce inter na tional des Fred Cooke espèces en péril et de la recherche sur les préoccupations Simon Fraser University d’importance nationale concernant les espèces sauvages. Il collabore avec les provinces, les territoires, Agence Parcs A.W. Diamond Canada et d’autres organismes fédéraux pour la recherche et Université du Nouveau-Brunswick aussi pour la gestion des espèces sauvages. Charles J. Henny Pour obtenir de plus amples renseignements sur le U.S. Geological Survey Service canadien de la faune ou ses pub lica tions, communiquer avec les : Raymond McNeill Université de Montréal Pub li ca tions Ross J. -

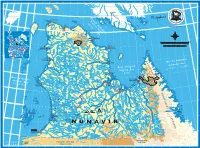

Printable-Map En.Pdf

84 º 83 º 82 º 81 º 80º 79º 78º 77º 76º 75º 74º 73º 72º 71º 70º 69º 68º 67º 66º 65º 64º 63º 62º 61º 60º 59º 58º Île 63 Salisbury º Island 63º Île Nottingham Island NUNA Coastº VUT Island Détr W h Cap Wolstenholme i t e S North Îles Digges Islands t Cape Wolstenholme BIG r CHARLES ISLAND a Bay Hudson i Fr d t ÎLE DE un oit ISLAND So obisher 62º es LOKS Digg wKp[4 Cape B AFFIN LAND 62º Nouvelle-France wrCn3 IVUJIVIK Fjord ISLAND Bay d’Hudson r Sugluk e iv Inlet Baie Déception Île R WWW.NUNAVIK-TOURISM.COM y a r Deception Bay Mansel � v u o Island r Str u Foul D n9lw5� Bay SALLUIT Havre Douglas Harb our ait EDGELL Jx ISLAND King-George Vanasse Bay Océan Arctique Lake Arctic Ocean GROËNLAND 6 GREENLAND Kovik River Kovik RESOLUTION ALASKA y a B (É.-U.) Bay vq3hJx6 ISLAND (U.S.A.) m W a 61 akeh KANGIQSUJUAQ º ver 61 le Ri Joy º Litt nituq Bay Puvir r Rive Parc national 0 100 200km NUNAVUT irnituq Puv des Pingualuit � r y e a CANADA iv r R e B t iv Océan ta R 0 50 100miles o t a Cape uk a Juet Pacifique Edmonton h t n Hopes Advance NUNAVIK C o Lake Vancouver Ik a Pacific Calgary Île Nantais Lake i D dx3b6 Seattle Ocean Smith xfo[4 Bylot Allemand QUÉBEC e Lake i QUAQTAQ Winnipeg Island �AKULIVIK Lake Montréal Cape a o s q u Ottawa M i t o B B Smith a y San Francisco Toronto Boston BUTTON � ISLANDS É.-U. -

Arctic Seabirds: Diversity, Populations, Trends, and Causes

ARCTIC SEABIRDS: DIVERSITY, POPULATIONS, TRENDS, AND CAUSES ANTHONY J. GASTON Wildlife Research Division, Environment Canada, National Wildlife Research Centre, Ottawa K1A 0H3, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Populations and trends of Arctic seabirds have been the subject of substantial research since the 1930s in Europe and Greenland and since the 1950s in North America. The marine waters of the Arctic support 44 species of seabirds comprising 20 genera. There are four endemic monotypic genera and an additional 25 species for which the bulk of the population is confined to Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. Most Arctic seabirds have large populations, with only two species comprising less than 100,000 individuals and many species numbering in the millions. Population trends for several widespread Arctic species have been negative in recent decades. Conversely, some sub-Arctic species are spreading northwards. Climate change with consequent changes in competition and predation, and intensifying development in the north, increasingly threaten Arctic seabirds. Changes in ice conditions are likely to have far-reaching and potentially irreversible results. Received 22 February 2011, accepted 26 May 2011. GASTON, A. J. 2011. Arctic seabirds: Diversity, populations, trends, and causes. Pages 147–160 in R. T. Watson, T. J. Cade, M. Fuller, G. Hunt, and E. Potapov (Eds.). Gyrfalcons and Ptarmigan in a Changing World, Volume I. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, USA. http://dx.doi.org/10.4080/ gpcw.2011.0201 Key words: Seabirds, diversity, population size, population trends, Arctic. SEABIRDS HAVE PROVIDED A SOURCE OF FOOD for Census of Arctic seabird colonies began in the Arctic peoples throughout their history and 1930s in Greenland (Salomonsen 1950) and most major seabird colonies within the range Russia (Uspenski 1956), the 1950s in eastern of the post-Pleistocene Inuit expansion are Canadian Arctic (Tuck 1961), the 1960s in associated with archaeological sites that attest Spitzbergen (Norderhaug et al. -

AMAP - CAFF Coordinated Monitoring Effort Status Report, Svolvær, April 2008 Table of Contents

AMAP - CAFF Coordinated Monitoring Effort Status Report, Svolvær, April 2008 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 Canada Arctic Biodiversity of Char.........................................................................2 Beluga.......................................................................................................6 CircumArctic Rangifer Monitoring and Assessment Network . ................9 International Tundra Experiment ...................... ..................................11 Polar Bears ............................................................................................12 Ringed Seal Populations. ....................................................................13 Ringed Seals. .....................................................................................15 Seabirds: Contaminants in Arctic Seabird Eggs ..................................16 Seabirds: Colony Monitoring ...............................................................18 Denmark, ENVOFAR ..........................................................................................20 Greenland & Nuuk Basic .........................................................................................21 The Faroe Is. Zackenberg Basic ...............................................................................28 Finland Big Deep Oligotrophic Lakes ...............................................................35 Pallas Soldankylä ...................................................................................36