Arctic Seabirds: Diversity, Populations, Trends, and Causes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia's Ring of Fire

Russia’s Ring of Fire Kamchatka, the Commander & Kuril Islands 26th May to7th June 2021 (13 days) Zodiac cruise & Auklet flocks by N. Russ The Pacific Ring of Fire manifests itself in numerous places on the rim of the Pacific Ocean – but nowhere more dramatically than in Russia’s Far East. Along one of the world’s most active plate boundaries, the Pacific plate subducts under the Eurasian plate and the resulting volcanic and geothermal activity has built a unique and amazing landscape. Upwelling from the deep trenches formed by this action and currents around the many islands means there is an abundance of food for both birds and marine mammals, making the seas here amongst the richest in the world. The region’s human history is as interesting and as fascinating as the geological history and it is closely connected to the oceans that surround it. The earliest people to settle in the RBL Russia - Ring of Fire Itinerary 2 region, the Ainu, lived from the sea. Explorer Vitus Bering and, at the height of the Cold war, Russia’s formidable Pacific Fleet, were based in the region. The secrecy surrounding the fleet resulted in the region being ‘closed’ even to Russians, who had to obtain special permits to travel to and within the area. It is only now, two decades since Perestroika, that people can travel relatively freely here, although there is still very little in the way of infrastructure for visitors. This voyage takes us where very few people have been – or are able to go. The region falls into three quite distinct and unique geographical regions: the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Commander Islands (the western extremity of the Aleutian chain of islands) and the Kuril Islands. -

Abstracts Annual Scientific Meeting ᐊᕐᕌᒍᑕᒫᕐᓯᐅᑎᒥᒃ ᑲᑎᒪᓂᕐᒃ

Abstracts Annual Scientific Meeting ᐊᕐᕌᒍᑕᒫᕐᓯᐅᑎᒥᒃ ᑲᑎᒪᓂᕐᒃ 2016 Réunion scientifique annuelle 5-9/12/2016, Winnipeg, MB ASM2016 Conference Program Oral Presentation and Poster Abstracts ABSTRACTS FROBISHER BAY: A NATURAL LABORATORY complete habitat characterization. This recent sampling FOR THE STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL effort recorded heterogeneous substrates composed of CHANGE IN CANADIAN ARCTIC MARINE various proportions of boulder, cobbles, gravel, sand HABITATS. and mud forming a thin veneer over bedrock at water depths less than 200 metres. Grab samples confirm Aitken, Alec (1), B. Misiuk (2), E. Herder (2), E. the relative abundance of mollusks, ophiuroids and Edinger (2), R. Deering (2), T. Bell (2), D. Mate(3), C. tubiculous polychaetes as constituents of the infauna Campbell (4), L. Ham (5) and V.. Barrie (6) in the inner bay. Drop video images captured a diverse (1) University of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Canada); epifauna not previously described from the FRBC (2) Department of Geography, Memorial University of research. A variety of bryozoans, crinoid echinoderms, Newfoundland (St. John’s, NL, Canada); sponges and tunicates recorded in the images remain (3) Polar Knowledge Canada (Ottawa, Ontario, to be identified. Habitat characterization will allow us Canada); to quantify ecological change in benthic invertebrate (4) Marine Resources Geoscience, Geological Survey of species composition within the habitat types represented Canada (Dartmouth, NS, Canada); at selected sampling stations through time. Such long- (5) Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office, Natural term studies are crucial for distinguishing directional Resources Canada (Iqaluit, NU, Canada); change in ecosystems. Marine Geological Hazards (6) Marine Geoscience, Geological Survey of Canada and Seabed Disturbance: Extensive multibeam (Sidney, BC, Canada) echosounding surveys have recorded more than 250 submarine slope failures in inner Frobisher Bay. -

Green Paper the Lancaster Sound Region

Green Paper The Lancaster Sound Region: 1980-2000 Issues and Options on the Use and Management of the Region Lancaster Sound Regional Study H.J. Dirschl Project Manager January 1982 =Published under the authority of the Hon. John C. Munro, P.C., M.P., Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa, 1981. 05-8297-020-EE-A1 Catalogue No. R72-164/ 1982E ISBN 0-662-11869 Cette publication peut aussi etre obtenue en francais. Preface In the quest for a "best plan" for Lancaster Sound criticisms. This feedback is discussed in detail in a and its abundant resources, this public discussion recently puolished report by the workshop chairman. paper seeks to stimulate a continued. wide-ranging, Professor Peter Jacobs, entitled People. Resources examination of the issues involved in the future use and the Environment: Perspectives on the Use and and management of this unique area of the Canadian Management of the Lancaster Sound Region. All the Arctic. input received during the public review phase has been taken into consideration in the preparation of the The green paper is the result of more than two years final green paper. of work by the Northern Affairs Program of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern From the beginning of the study, it was expected that Development, in co-operation with the government of to arrive at an overall consensus of the optimum fu the Northwest Territories and the federal departments ture use and management of the Lancaster Sound of Energy, Mines and Resources, Environment. region would require intensive public discussion fol Fisheries and Oceans. -

Field Guides Birding Tours Galapagos Iii 2012

Field Guides Tour Report GALAPAGOS III 2012 Aug 4, 2012 to Aug 14, 2012 George Armistead & Peter Freire The ubiquitous Blue-footed Booby is kind of the mascot of the Galapagos islands, enchanting visitors, be they bird watchers or not. In the islands, everybody loves boobies. (Photo by guide George Armistead) The Galapagos islands are a dream destination for every nature enthusiast, and we got to see first-hand why the enchanted isles are unique and so alluring, especially for birders. We arrived on Baltra and quickly made our way to the lovely Nemo II, and after settling in and meeting the friendly crew, we were off! Our first visit found us circling legendary Daphne Major, and we were extremely pleased to see a handful of Galapagos Martins working the top of the island for bugs. At North Seymour we were overrun with land iguanas, seeing about 20 of them, as we also side-stepped nesting frigatebirds and Blue-footed Boobies, and took note of our first Galapagos Doves. We sailed overnight for Floreana, where we had a nice hike amid the pirate caves, and tallied our only Medium Tree-Finches of the trip, before loading up and heading to the other side of the island. At Champion-by-Floreana we found a most confiding family of critically endangered Floreana Mockingbirds. That night we headed west for the Bolivar Channel, beginning the following day by walking the lava fields at Punta Moreno, tallying more great sightings of martins, enjoying lengthy studies of some very close flamingos and White-cheeked Pintails, and also noting all three types of cacti. -

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2020 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2020 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 7 April 2021 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 starting in the Pacific Ocean to reach the Atlantic Oceam, but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 319 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2020 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (marked ‘cp’). -

Hudson Strait-Ungava Bay Common Eider Surveys

Hudson Strait Common Eider and Polar Bear Surveys 2014 Field Season Report Project Overview Our ongoing research investigates the status of common eiders, red-throated loons and other ground nesting birds nesting on coastal islands in the Hudson Strait, Ungava Bay, and Foxe Basin marine regions of the eastern Canadian Arctic. There is considerable interest in the north relating to issues of human health and food security, as well as wildlife conservation and sustainable harvest. We are focusing on several emerging issues of significant ecological and conservation importance: 1. Quantifying the extent of polar bear predation on eider nests as sea ice diminishes. 2. Quantifying the spread and severity of avian cholera outbreaks among northern eider populations. 3. Quantifying the distribution and abundance of birds nesting on coastal islands in support of environmental sensitivity mapping and marine emergency response planning. Clockwise from top left: Adamie Mangiuk conducting surveys in Digges Sound, Nik Clyde measuring ponds on an eider colony, a Common Eider on her nest. 2014 Research Highlights Avian Cholera and Marine Birds Avian cholera is one of the most lethal diseases for birds in North America. Although it has circulated in southern Canada and the United States for many years, its emergence among eiders in the north is new. To better understand transmission dynamics and potential population level impacts for eiders we have undertaken sampling across the eastern Arctic. We are examining the geographic extent of the outbreaks, as well as the origins, virulence and evolution of the disease. Map of survey locations and the year in which they were completed. -

Qikiqtani Region Arctic Ocean

OVERVIEW 2017 NUNAVUT MINERAL EXPLORATION, MINING & GEOSCIENCE QIKIQTANI REGION ARCTIC OCEAN OCÉAN ARCTIQUE LEGEND Commodity (Number of Properties) Base Metals, Active (2) Mine, Active (1) Diamonds, Active (2) Quttinirpaaq NP Sanikiluaq Mine, Inactive (2) Gold, Active (1) Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions 10 CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply ISLANDS Belcher MBS Migratory Bird Sanctuary NP National Park Nares Strait Islands NWA National Wildlife Area - ÉLISABETH Nansen TP Territorial Park WP Wildlife Preserve WS Wildlife Sanctuary Sound ELLESMERE ELIZABETHREINE ISLAND Inuit Owned Lands (Fee simple title) Kane Surface Only LA Agassiz Basin Surface and Subsurface Ice Cap QUEEN Geological Mapping Programs Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office ÎLES DE Kalaallit Nunaat Boundaries Peary Channel Müller GREENLAND/GROENLAND NLCA1 Nunavut Settlement Area Ice CapAXEL Nunavut Regions HEIBERG ÎLE (DENMARK/DANEMARK) NILCA 2 Nunavik Settlement Area ISLAND James Bay WP Provincial / Territorial D'ELLESMERE James Bay Transportation Routes Massey Sound Twin Islands WS Milne Inlet Tote Road / Proposed Rail Line Hassel Sound Prince of Wales Proposed Steensby Inlet Rail Line Prince Ellef Ringnes Icefield Gustaf Adolf Amund Meliadine Road Island Proposed Nunavut to Manitoba Road Sea Ringnes Eureka Sound Akimiski 1 Akimiski I. NLCA The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Island Island MBS 2 NILCA The Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement Norwegian Bay Baie James Boatswain Bay MBS ISLANDSHazen Strait Belcher Channel Byam Martin Channel Penny S Grise Fiord -

The Forgotten Journey Huw Lewis-Jones Revisits a Pioneering, Ill-Fated Expedition to Map the Arctic

Vitus Bering, leader of the eighteenth-century Great Northern Expedition, died en route and was buried here, in the Commander Islands (pictured in 1980). POLAR EXPLORATION The forgotten journey Huw Lewis-Jones revisits a pioneering, ill-fated expedition to map the Arctic. he Great Northern Expedition was an Yet Bering’s brainchild books: Corey Ford’s Where the Sea Breaks Its immense eighteenth-century enter- was certainly one of Back (Little, Brown, 1966) and Steller’s Island prise that redrew the Arctic map. Led the largest, longest and (Mountaineers, 2006) by Dean Littlepage. Tby Danish captain Vitus Bering, it set out in most costly expedi- Bown’s synthesis of these “tragic and 1733 from St Petersburg, Russia. Over the tions mounted in the ghastly” final months is well written. He also next decade, a dwindling cavalcade crossed eighteenth century. goes to great lengths to detail the arduous thousands of miles of Siberian forest and Its budget, at around early phases, essentially an unending gauntlet swamp and then, in ships built by hand, 1.5 million roubles, of implausible logistics. Everything needed TARASEVICH/SPUTNIK/ALAMY V. struck out towards the unknown shores of was roughly one-sixth for the voyage — from shipbuilding gear North America. Sponsor Peter the Great of the annual income Island of the Blue and supplies to anchors, sails and cannon- had envisioned a grand campaign to elevate of the Russian state. As Foxes: Disaster balls — had to be hauled overland, by sledge, Russia’s standing in the world, with its scien- an example of commit- and Triumph horse and raft. -

89 Seabird 28 (2015)

Reviews REVIEWS Penguins: Their World, Their Ways By Tui articles are a master-class in the communi- De Roy, Mark Jones & Julie Cornthwaite. cation of scientific research to a much wider Christopher Helm, London. 2013. ISBN public than published papers would 978-1-4081-5212-6. Hundreds of colour normally reach. All the contributors are to be congratulated on the clarity and readability photographs, distribution maps. Hardback. of their accounts. I’m not going to pick out £35.00. any for particular comment, although it was I’ve long passed the age where I expect appropriate that it was given to Conrad much from birthday presents, but earlier this Glass (the ‘Rockhopper Copper’) to describe year I dropped a subtle hint to the wife well the unfortunate events of the 2011 MV in advance, and on the day was delighted to Oliva oil spill at Tristan da Cuhna. unwrap and flick through this book; reading it properly had to wait until the summer The final section (Species Natural History), field season ended! The format follows that compiled by Julie Cornthwaite, gives each of Albatross: Their World, Their Ways species a double-page spread summarising (reviewed in SEABIRD 22). First, the 18 facts and figures, and even these accounts species of penguin recognised here are average 8–9 colour photos. The only described in a series of essays covering the references in the book appear for each different taxonomic groups (e.g. Island species under Taxonomic source and Dandies: The Crested Penguins) in which Tui Conservation status, but these are not listed De Roy’s evocative text is almost lost among in full, although there is a short section on a multitude of stunning photographs, further reading and a very useful list of covering penguins in habitats ranging from websites where the reader can find out mangroves of the Galapagos, New Zealand’s much more information. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

Lincoln Sea Hall Basin MARINE ATLAS ARCTIC CANADA’S GREENLAND Ellesmere Island Kane Basin Nares Strait N nd ansen Sou s d Axel n Sve Heiberg rdr a up Island l Ch ann North CANADA’S s el I Pea Water ry Ch a h nnel Massey t Sou Baffin e Amund nd ISR Boundary b Ringnes Bay Ellef Norwegian Coburg Island Grise Fiord a Ringnes Bay Island ARCTIC MARINE z Island EEZ Boundary Prince i Borden ARCTIC l Island Gustaf E Adolf Sea Maclea Jones n Str OCEAN n ait Sound ATLANTIC e Mackenzie Pe Ball nn antyn King Island y S e trait e S u trait it Devon Wel ATLAS Stra OCEAN Q Prince l Island Clyde River Queens in Bylot Patrick Hazen Byam gt Channel o Island Martin n Island Ch tr. Channel an Pond Inlet S Bathurst nel Qikiqtarjuaq liam A Island Eclipse ust Lancaster Sound in Cornwallis Sound Hecla Ch Fitzwil Island and an Griper nel ait Bay r Resolute t Melville Barrow Strait Arctic Bay S et P l Island r i Kel l n e c n e n Somerset Pangnirtung EEZ Boundary a R M'Clure Strait h Island e C g Baffin Island Brodeur y e r r n Peninsula t a P I Cumberland n Peel Sound l e Sound Viscount Stefansson t Melville Island Sound Prince Labrador of Wales Igloolik Prince Sea it Island Charles ra Hadley Bay Banks St s Island le a Island W Hall Beach f Beaufort o M'Clintock Gulf of Iqaluit e c n Frobisher Bay i Channel Resolution r Boothia Boothia Sea P Island Sachs Franklin Peninsula Committee Foxe Harbour Strait Bay Melville Peninsula Basin Kimmirut Taloyoak N UNAT Minto Inlet Victoria SIA VUT Makkovik Ulukhaktok Kugaaruk Foxe Island Hopedale Liverpool Amundsen Victoria King -

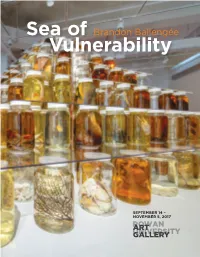

Brandon Ballengée Vulnerability

Sea of Brandon Ballengée Vulnerability SEPTEMBER 14 – NOVEMBER 5, 2017 ROWANART UNIVERSITYGALLERY ‘TRANSDISCIPLINARY’ IS HOW BEST TO DESCRIBE BRANDON BALLENGÉE’S PRACTICE. He is an artist, biologist and environmental educator who cre- ates artworks inspired from his ecological feldwork and lab- oratory research. His scientific research informs his artistic inquiry resulting in works that are balanced in its artistic and scientifc statements. In Sea of Vulnerability we presented a se- ries of his artworks in the form of installations, assemblages, and mixed media that ofer dramatic visual representations of species that are in decline, threatened, or already lost to extinc- tion. The results are beautifully composed artistic expressions that are also informative of some of our most pressing envi- ronmental issues. In his work Collapse for example we encounter a monumental pyramid of preserved aquatic specimens from the Gulf of Mexico meant to reference the fragile inter-relationship between gulf species and the food chain post the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the largest oil spill in human history. The narrative expressed in the work is dire, but visually the installation is a stun- ning example of formal visual aesthetics. The 455 jars (containing 370+ diferent species) are me- ticulously spaced into evenly measured rows punctuated by various shades of amber placed in purposeful sequences. The precision of the placement invites the viewer in where they encoun- ter the meaning in the work. As you follow the rows towards the top many of the glass jars are 1 Collapse: 2012, preserved specimens, glass and Carosafe preservative solutions, 9 x 12.8 x 12.8 feet, in scientifc collabora- tion with Todd Gardner, Jack Rudloe, Brian Schiering and Peter Warny courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York. -

Behind the Plan to Protect the Serengeti of the Arctic

Behind the Plan to Protect the Serengeti of the Arctic newsdeeply.com /oceans/articles/2017/08/24/behind-the-plan-to-protect-the-serengeti-of-the-arctic For nearly 50 years, Inuit in northeastern Canada have been pushing for federal protection of the fragile ecosystem in Lancaster Sound that they subsist on. The Sound, which forms the eastern gateway to the Northwest Passage, has been called the Serengeti of the Arctic for its rich diversity of wildlife, including narwhals, belugas and polar bears. It’s also believed to hold some of the world’s largest offshore oil reserves. The Inuit’s perseverance finally paid off last week with an announcement by the Canadian government, the territory of Nunavut and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) that Lancaster Sound – now to be known as Tallurutiup Imanga – will be protected by a national marine conservation area much larger than one proposed just seven years ago. Once enacted, the conservation area will mean a complete ban on oil and gas activities, as well as deep-sea mining and ocean dumping. The announcement marks a triumph for the Inuit after decades of negotiation and, at times, strong disagreement over how the area should be managed. “We are patient people,” acknowledged P.J. Akeeagok, president of the QIA, which represents some 14,000 Inuit, including five communities within the conservation area, “but this agreement provides an amazing opportunity.” 1/5 The conservation area will span some 109,000 square km (42,200 square miles) – more than double what was first proposed by the federal government in 2010, after the Inuit went to court to block seismic testing – making it Canada’s largest protected area.