2020 Steinmeyer Allison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

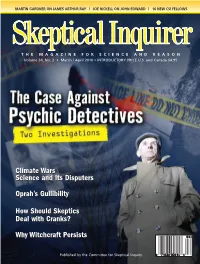

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

James Arthur Ray: New Age Guru and Sweat Lodge Culprit

SI March April 2010 pgs:SI J A 2009 1/22/10 11:39 AM Page 19 NOTES OF A FRINGE WATCHER M A R T I N G A R D N E R James Arthur Ray: New Age Guru and Sweat Lodge Culprit n recent years Sedona, Arizona, has become a popular haven for New IAge cults of all shades. Why Sedona? Partly because of its superb scenery and sunlight, and partly because of the belief that it swarms with invisible “vortexes” from which one can draw cosmic or spiritual energy. There are also nearby Indian tribes with herbal remedies and powerful witch doctors. On October 8, 2009, at a New Age retreat in Angel Valley, Arizona, near Sedona, another of Oprah Winfrey’s and Larry King’s guests ran into deep trouble. More than sixty followers of James Arthur Ray were crammed into a small tent Ray brought to an unbearable tem- perature with heated rocks. At the end of the first session of what Ray calls a “sweat lodge” meeting, guests were throwing up and passing out while Ray stood guard at the tent’s flap entrance to prevent guests from leaving. By the meeting’s end, some twenty followers were taken to hospitals where three died: Kirby Brown, thirty- eight; Liz Newman, forty-eight; and James Shore, forty. Who the devil is James Ray? He was Martin Gardner is author of more than sev- enty books, most recently The Jinn from Hyperspace (Prometheus Books, 2008) and When You Were a Tadpole and I Was a Fish, and Other Specula tions About This and That (Hill and Wang, 2009). -

Proceedings: Sixth Biennial Conference on Religion and American Culture

Proceedings: Sixth Biennial Conference on Religion and American Culture June 6-9, 2019 The Alexander Hotel Indianapolis, Indiana hosted by The Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture in the IU School of Liberal Arts Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and Religion & American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation Editors Philip Goff Lauren Schmidt Nate Wynne © 2019 The Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Proceedings: Sixth Biennial Conference on Religion and American Culture, June 2019 Table of Contents Introduction Philip Goff, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis 4 Part I Teaching American Religion Kathleen Holscher, University of New Mexico 6 Carolyn M. Jones Medine, University of Georgia 8 Douglas Thompson, Mercer University 12 Translating Scholarship Heath W. Carter, Valparaiso University 15 Robert Orsi, Northwestern University 17 Mira Sucharov, Carleton University 19 Part II Religion and Refugees Melissa Borja, University of Michigan 22 Tricia C. Bruce, University of Notre Dame 25 Gale L. Kenny, Barnard College 27 Different Narratives in Religion and American Politics Prema Kurien, Syracuse University 30 David Harrington Watt, Haverford College 32 Aubrey L. Westfall, Wheaton College 34 Part III Religion and Crisis Amanda J. Baugh, California State University, Northridge 37 John Corrigan, Florida State University 39 Anthony Petro, Boston University 41 New Religious Movements Embodied Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis 44 Leonard Norman Primiano, Cabrini University 46 Judith Weisenfeld, Princeton University 49 Part IV Science, Technology, and Spirituality Sylvester A. Johnson, Virginia Tech 53 Hillary Kaell, Concordia University 55 Christopher White, Vassar College 59 Looking Ahead Rudy V. -

Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) 1 Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) 1 Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also called the Sioux Treaty of 1868) was an agreement between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation[1] signed in 1868 at Fort Laramie in the Wyoming Territory, guaranteeing to the Lakota ownership of the Black Hills, and further land and hunting rights in South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana. The Powder River Country was to be henceforth closed to all whites. The treaty ended Red Cloud's War. In the treaty, as part of the U.S. vendetta to General William T. Sherman (third from left) and Commissioners in Council with "divide and conquer", the U.S. included all chiefs and headmen of different bands of the Sioux, including Arapaho Indians, Ponca lands in the Great Sioux Reservation. Fort Laramie, Wyoming, 1868. Photograph by Alexander Gardner Conflict between the Ponca and the Sioux/Lakota, who now claimed the land as their own by U.S. law, forced the U.S. to remove the Ponca from their own ancestral lands in Nebraska to poor land in Oklahoma. The treaty includes an article intended to "ensure the civilization" of the Lakota, financial incentives for them to farm land and become competitive, and stipulations that minors should be provided with an "English education" at a "mission building." To this end the U.S. government included in the treaty that white teachers, blacksmiths, a farmer, a miller, a carpenter, an engineer and a government agent should take up residence within the reservation. -

The Secret, Cultural Property and the Construction of the Spiritual Commodity

Cultural Studies Review volume 18 number 2 September 2012 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 52–73 Guy Redden 2012 The Secret, Cultural Property and the Construction of the Spiritual Commodity GUY REDDEN UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY According to John Frow, ‘Every society draws a line between those things that can be privately owned and freely exchanged, and those whose circulation is restricted’.1 Religion is one domain conventionally considered inimical to market exchange. Items deemed sacred may be seen as paradigmatic of goods that are inalienable from the group that holds them dear. Special provisions are often made to restrict their circulation and control their significance. Historically in the West this has involved the regulation of religious ideation and practice by Christian churches. Even while the formal influence of churches over the polity has waned, their institutional direction of matters of the spirit has been maintained. However, numerous commentators have observed the increased commercialisation of religion over recent years.2 This includes both the literal market exchange of religious goods and the ingression of market-like rationalities into established religions that seek to sustain their contemporary relevance by embracing marketing strategies, elements of popular culture and consumer lifestyle expectations. There are numerous questions about the nature and extent of such ISSN 1837-8692 changes, and how they may be indicative of broader societal issues. The rise of market-oriented religiosity has been attributed to the emergence of postwar consumer culture and to other secularising tendencies—such as the social influence of science—that diminish the previous authority of religion and spur religious organisations to recast their appeal.3 It is now common for religious practice to be thought of as sharing affinities with secular forms of consumption in offering participants opportunities to pursue personal identity.4 The commodification of religious goods is less often conceptualised as a production process. -

Los Angeles Lawyer December 2016

THE MAGAZINE OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION DECEMBER 2016 / $5 EARN MCLE CREDIT PLUS NEW SOCIAL PARTNERSHIP MEDIA IN AUDIT RULES LITIGATION page 24 page 30 Estate Form 8971 page 12 On Direct: Eli Broad page 8 Ready Capital Los Angeles lawyer Mark Hiraide analyzes the regulatory regime and impact of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act page 18 FEATURES 18 Ready Capital BY MARK HIRAIDE The Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act provides new ways to conduct public offerings exempt from SEC registration thereby legalizing crowdfunding 24 Finding the PATH BY TERENCE FLOYD CUFF Designation of a partnership representative to handle IRS audits and distinguishing the review year from the adjustment year of the audit are key elements in new partnership audit rules found in the Protecting Americans From Tax Hikes Act Plus: Earn MCLE credit. MCLE Test No. 263 appears on page 27. 30 Damage Control in the TMZ Era BY MANNY MEDRANO AND RALPH FRAMMOLINO Long before the rise of social media, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that attorneys have not only the right but also the obligation to defend their clients in the court of public opinion Los Angeles Lawyer DEPARTME NTS the magazine of the Los Angeles County 8 On Direct 12 Tax Tips Bar Association Eli Broad New rules for basis consistency December 2016 INTERVIEW BY DEBORAH KELLY reporting of inherited assets BY MEGAN FERKEL EARHART AND Volume 39, No. 9 10 Barristers Tips PAUL GORDON HOFFMAN Practical considerations in starting COVER PHOTO: TOM KELLER a solo practice 36 Closing Argument BY JOHN D. -

White Papers

MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP ROBERT K .JOHNSONt STUART N. SENATOR 355 SOUTH GRAND AVENUE ALAN V. FRIEDMANt MARTIN D. BERN MONlKA S. WIENER WESLEY SHIH RONALD L OLSONt DANIEL P_ COLLINS LYNN HEALEY SCADUTO .JACOB S. KREILKAMP RICHARD S. VOLPERT RICHARD E. DROOYAN THIRTY-FIFTH FLOOR ERIC J. LORENZINI PAUL.J. KATZ DENNiS C. BROWNf ROBERT L DELL ANGELO KATHERINE K, HUANG JONATHAN M. WEISS ROBERT E. DENHAM BRUCE A. ABBOTT LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90071-1560 LINDSAY D. M<:CASKILL ELISABETH .J. NEUBAUER .JEFFREY r. WEINBERGER JONATHAN E. ALTMAN KATE K. ANDERSON ERIC P, TUTTLE CARY B, LERMAN ALISON J. MARKOVITZ HEATHER E. TAKAHASHI MARY ANN TODD TELEPHONE (213) 683-9100 CHARLES D. SIEGAL MICHAEL J. O'SULLIVAN SUSAN TRAUB BOYD KRISTINA L WILSON RONALD K. MEYER KELLY M. KLAUS .JENNIFER L POLSE KEVIN A GOLDMAN GREGORY P. STDNE DAVID B. GOLDMAN FACSIMILE (213) 687-3702 BRIAN R. HOCHLEUTNER ROBYN KAU BACON BRAD D. BRIAN BURTON A, GROSS GRANT A. DAVIS-DENNY BERNARD A. ESKANDARI BRADLEY S, PHILLIPS KEVIN S. MASUDA ,JASON RANTANEN .JENNY M . .JIANG GEORGE M. GARVEY HO.JOON HWANG REBECCA GOSE LYNCH KEITH R,D. HAMILTON, II WILLIAM D. TEMKO KRISTIN S. ESCALANTE .JONATHAN H. BLAVIN SORAYA C. KELLY STEVEN L GUISEt DAVID C. DINIELLI KAREN .J, EPHRAIM PATRICK ANDERSON ROBERT B. KNAUSS ANDREA WEISS .JEFFRIES MICHELLE T. FRIEDLAND .JEFFREY Y. WU STEPHEN M. KRISTOVICH PETER A. DETRE L1KA C. MIYAKE YUVAL MILLER .JDHN W. SPIEGEL PAUL J. WATFORD 560 MISSION STREET MELINOA EADES L£MQINE MARK R. CONRAD TERRY E. SANCHEZ DANA S. TREISTER ANDREW W. -

NR2202 05 Crockford 93..114

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography How Do You Know When You’re in a Cult? The Continuing Influence of Peoples Temple and Jonestown in Contemporary Minority Religions and Popular Culture Susannah Crockford ABSTRACT: This article examines representations of Peoples Temple in popular culture through the lens of mimesis, understood as a process of repetition and re-creation of specific elements. This process produces what is understood as a “cult” in popular culture, which is divorced from the complex historical reality of Peoples Temple. Three symbolic strands combine to construct the concept of a “cult”: the power of a charismatic leader, isolation from outside influences, and consuming poison, or “drinking the Kool-Aid.” In popular culture, these symbols are used in order to apportion blame, to learn lessons, and to act as a warning. Peoples Temple was a collective trauma for American culture as well as an individual trauma for survivors. The process of mimesis, therefore, is a way of both memorializing and reinscribing this trauma on a cultural level. Examples from ethnographicresearchconductedinSedona, Arizona, are used to illustrate how symbols of Jonestown generated by cultural mimesis continue to be invoked by participants in contemporary minority religions as a way to signal their concern about whether they belong to a cult. KEYWORDS: minority religions, Peoples Temple, cults, United States of America, mimesis, popular culture Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 22, Issue 2, pages 93–114. ISSN 1092-6690 (print), 1541-8480. -

The Lakota Sun Dance and Ethical Intercultural Exchange

IK: Other Ways of Knowing Peer Reviewed Dancing Together: The Lakota Sun Dance and Ethical Intercultural Exchange Ronan Hallowell Volume: 3 Issue: 1 Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Southern California Pg 30-52 Reflecting upon my twenty years of participation in several Lakota Sun Dance ceremony communities, this article explores ethical questions that arise from non-Native people practicing traditional Native American ceremonies, especially the Lakota Sun Dance. Through personal stories of lessons learned attending twenty Lakota Sun Dances, being taught for many years to sing ceremonial songs by a fluent Lakota singer/elder, and a historical overview of the Sun Dance, I discuss paths toward mutually enhancing intercultural communication based on respect, shared sacrifice, generosity, integrity, and the cultivation of long-term thinking for the well-being of people and the planet, now, and for generations to come. Keywords: Native American Sun Dance; Lakota Traditions; Intercultural Communication; Ceremony; Ethics In the book Research Is Ceremony (2008), Cree scholar Shawn Wilson grapples with the challenges of conducting and articulating scholarly work that employs indigenous research methods in ways that are guided by, and in service to, the concerns of particular indigenous communities that have experienced Western scientific research as invasive, colonial, and lacking respect or understanding of indigenous ways of knowing. Wilson also discusses the struggles indigenous scholars face in regards to having their work taken seriously in the academy. His work primarily focuses on indigenous scholars in Canada and Australia, but many of his insights are relevant to other indigenous scholars and non-indigenous scholars interested in these conversations. -

Carlos Castaneda – and His Most Influential Book

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Frederika Ratkovičová A Criticism and Defence of Neoshamanism Bachelor`s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, for his patient guidance and advice. Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………...…….…..….1 1 Shamanism and Neoshamanism: Background……………….….….3 Shamanism…………………………………………………….3 Neoshamanism………………………………………………...6 Castaneda………………………………………………...……7 2 Criticism of neoshamanism…………………………….…………..13 3 Defence of neoshamanism…………………………….…….……..22 4 Conclusion…………………………………………………………29 Works Cited……………………………………………………….…31 Summary…………………………………………………………..…35 Resumé……………………………………………………………….36 Introduction Native American shamanism consists of wide set of beliefs which were rooted a long time ago. Nowadays, people are getting back to this tradition through contemporary shamanism which they call neoshamanism. This thesis focuses on the dispute between traditional shamanism and neoshamanism. Native American people, and shamans in particular, are dissatisfied with their traditions being used by non-Natives claiming that it is a misappropriation of their traditions and that they only do it for their own profit. The aim of this thesis is to acquaint the reader with possible misuse of -

PDF Download

‘Quaker Sweat’ as Intangible Heritage Benjamin Gratham Aldred ‘Quaker Sweat’ as Intangible Heritage ‘Quaker Sweat’ as Intangible Heritage Benjamin Gratham Aldred Kendall College, Chicago, IL, USA ABSTRACT In 2004, a small ritual to be held at a Quaker conference in Massachusetts stirred up a big controversy. The ‘Quaker Sweat’, a syncretic ritual drawing on Lakota, Cherokee and Religious Society of Friends sources, drew protests from a local Native American group. The controversy that emerged within the Friends General Conference, a national Quaker group, highlights the complex dynamics of the cultural property debate. Does the ritual belong to George Price, who developed it? Does the ritual belong to the Lakota, who taught him and gave him permission? Does the ritual belong to the Wampanoag on whose land it was to take place? In the ensuing debate, questions of syncretism and property are examined, taking into account the complex issues of personal versus cultural value, the role of history and experience in cultural property and the complexities of different cultural models of agency related to shared cultural forms. How does a cultural property debate develop between interested actors without the intervention of governments or inter-governmental bodies? Keywords religion, syncretism, education, ritual, sweat lodge, Lakota, Religious Society of Friends(Quakers), Wampanoag, Native American, James Arthur Ray Introduction leaders, were a synthesis of Native American ritual forms Who owns the Quaker Sweat? In 1989, a man named and Quaker philosophies. The case is perhaps of much George Price began conducting syncretic rituals he wider interest in relation to the increasing use of called ‘Quaker Sweat Lodges’. -

Witnessing Whiteness Workshop Series

Witnessing Whiteness The Need to Talk About Race and How to Do It Workshop Series A companion curriculum to the book, Witnessing Whiteness 2nd Edition Created by Shelly Tochluk Education Department Mount Saint Mary’s University – Los Angeles Web Publication Date January 2010 1.1-1 Why Pay Attention to Race? Witnessing Whiteness Chapter 1 Workshop 1.1 Dear Facilitator(s), This workshop series was carefully crafted, reviewed (by a multiracial team), and revised with several important issues in mind. The series is intended to… 1. Offer an 11 part, sequential process that corresponds to the reading of the book, Witnessing Whiteness, 2nd Edition. Understandably, facilitators, for various reasons, might want to use one or more of the workshops as stand alone events without sufficient time for participants to a) read the corresponding book chapters or b) move through the entire series. Yet, please understand that moving through these workshops without having read the corresponding book chapter will markedly reduce its effectiveness. It will make moving through the workshop more challenging and is NOT recommended. Understandings gained from one workshop are also important for subsequent workshops. 2. Respond to particular group needs. Recognizing that some groups may not be able to implement each workshop for the entire time suggested, some approved modifications can be found at the end of each workshop agenda. Only modify these workshops when absolutely required. 3. Create a welcoming, inviting space where participants feel free to speak the truth of their experience without fear of shaming or reprisal. It is essential for facilitators to understand that even when participants hold views that are counter to the themes in the book/series, a hallmark of both the book and the series is that people should be gently led into a new way of seeing.