Witnessing Whiteness Workshop Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Names in Marilynne Robinson's <I>Gilead</I> and <I>Home</I>

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 139–49 Names in Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Home Susan Petit Emeritus, College of San Mateo, California, USA The titles of Marilynne Robinson’s complementary novels Gilead (2004) and Home (2008) and the names of their characters are rich in allusions, many of them to the Bible and American history, making this tale of two Iowa families in 1956 into an exploration of American religion with particular reference to Christianity and civil rights. The books’ titles suggest healing and comfort but also loss and defeat. Who does the naming, what the name is, and how the person who is named accepts or rejects the name reveal the sometimes difficult relationships among these characters. The names also reinforce the books’ endorsement of a humanistic Christianity and a recommitment to racial equality. keywords Bible, American history, slavery, civil rights, American literature Names are an important source of meaning in Marilynne Robinson’s prize-winning novels Gilead (2004) and Home (2008),1 which concern the lives of two families in the fictional town of Gilead, Iowa,2 in the summer of 1956. Gilead is narrated by the Reverend John Ames, at least the third Congregationalist minister of that name in his family, in the form of a letter he hopes his small son will read after he grows up, while in Home events are recounted in free indirect discourse through the eyes of Glory Boughton, the youngest child of Ames’ lifelong friend, Robert Boughton, a retired Presbyterian minister. Both Ames, who turns seventy-seven3 that summer (2004: 233), and Glory, who is thirty-eight, also reflect on the past and its influence on the present. -

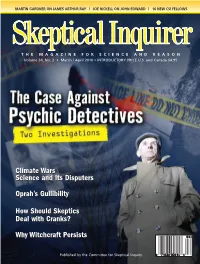

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

1 the Importance of Sundown Towns

1 The Importance of Sundown Towns “Is it true that ‘Anna’stands for ‘Ain’t No Niggers Allowed’?”I asked at the con- venience store in Anna, Illinois, where I had stopped to buy coffee. “Yes,” the clerk replied. “That’s sad, isn’t it,” she added, distancing her- self from the policy. And she went on to assure me, “That all happened a long time ago.” “I understand [racial exclusion] is still going on?” I asked. “Yes,” she replied. “That’s sad.” —conversation with clerk, Anna, Illinois, October 2001 ANNA IS A TOWN of about 7,000 people, including adjoining Jonesboro. The twin towns lie about 35 miles north of Cairo, in southern Illinois. In 1909, in the aftermath of a horrific nearby “spectacle lynching,” Anna and Jonesboro expelled their African Americans. Both cities have been all-white ever since.1 Nearly a century later, “Anna” is still considered by its residents and by citizens of nearby towns to mean “Ain’t No Niggers Allowed,” the acronym the convenience store clerk confirmed in 2001. It is common knowledge that African Americans are not allowed to live in Anna,except for residents of the state mental hospital and transients at its two motels. African Americans who find themselves in Anna and Jonesboro after dark—the majority-black basketball team from Cairo, for example—have sometimes been treated badly by residents of the towns, and by fans and stu- dents of Anna-Jonesboro High School. Towns such as Anna and Jonesboro are often called “sundown towns,” owing to the signs that many of them for- merly sported at their corporate limits—signs that usually said “Nigger,Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on You in __.” Anna-Jonesboro had such signs on Highway 127 as recently as the 1970s. -

James Arthur Ray: New Age Guru and Sweat Lodge Culprit

SI March April 2010 pgs:SI J A 2009 1/22/10 11:39 AM Page 19 NOTES OF A FRINGE WATCHER M A R T I N G A R D N E R James Arthur Ray: New Age Guru and Sweat Lodge Culprit n recent years Sedona, Arizona, has become a popular haven for New IAge cults of all shades. Why Sedona? Partly because of its superb scenery and sunlight, and partly because of the belief that it swarms with invisible “vortexes” from which one can draw cosmic or spiritual energy. There are also nearby Indian tribes with herbal remedies and powerful witch doctors. On October 8, 2009, at a New Age retreat in Angel Valley, Arizona, near Sedona, another of Oprah Winfrey’s and Larry King’s guests ran into deep trouble. More than sixty followers of James Arthur Ray were crammed into a small tent Ray brought to an unbearable tem- perature with heated rocks. At the end of the first session of what Ray calls a “sweat lodge” meeting, guests were throwing up and passing out while Ray stood guard at the tent’s flap entrance to prevent guests from leaving. By the meeting’s end, some twenty followers were taken to hospitals where three died: Kirby Brown, thirty- eight; Liz Newman, forty-eight; and James Shore, forty. Who the devil is James Ray? He was Martin Gardner is author of more than sev- enty books, most recently The Jinn from Hyperspace (Prometheus Books, 2008) and When You Were a Tadpole and I Was a Fish, and Other Specula tions About This and That (Hill and Wang, 2009). -

47 Free Films Dealing with Racism That Are Just a Click Away (With Links)

47 Free Films Dealing with Racism that Are Just a Click Away (with links) Ida B. Wells : a Passion For Justice [1989] [San Francisco, California, USA] : Kanopy Streaming, 2015. Video — 1 online resource (1 video file, approximately 53 min.) : digital, .flv file, sound Sound: digital. Digital: video file; MPEG-4; Flash. Summary Documents the dramatic life and turbulent times of the pioneering African American journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader of the post-Reconstruction period. Though virtually forgotten today, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a household name in Black America during much of her lifetime (1863-1931) and was considered the equal of her well-known African American contemporaries such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice documents the dramatic life and turbulent times of the pioneering African American journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader of the post-Reconstruction period. Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison reads selections from Wells' memoirs and other writings in this winner of more than 20 film festival awards. "One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap." - Ida B. Wells "Tells of the brave life and works of the 19th century journalist, known among Black reporters as 'the princess of the press, ' who led the nation's first anti-lynching campaign." - New York Times "A powerful account of the life of one of the earliest heroes in the Civil Rights Movement...The historical record of her achievements remains relatively modest. This documentary goes a long way towards rectifying that egregious oversight." - Chicago Sun-Times "A keenly realized profile of Ida B. -

American Pogrom: the East St. Louis Race Riot and Black Politics

Lumpkins.1-108 6/13/08 4:35 PM Page 1 Introduction ON JULY and , , rampaging white men and women looted and torched black homes and businesses and assaulted African Americans in the small industrial city of East St. Louis, Illinois. The mob, which included police officers and National Guardsmen, wounded or killed many black residents and terrorized others into fleeing the city. The rampagers acted upon a virulent form of racism that made “black skin . a death warrant,” in the words of white newspaper reporter Jack Lait of the St. Louis Repub- lic. According to one African American eyewitness, “When there was a big fire, the rioters . stop[ped] to amuse themselves, and [threw black] children . into the fire.” The riots disrupted interstate commerce and in- dustrial production, prompting Illinois authorities to mobilize additional National Guard units to suppress the mass violence. When the terror ended, white attackers had destroyed property worth three million dollars, razed several neighborhoods, injured hundreds, and forced at least seven thousand black townspeople to seek refuge across the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri. By the official account, nine white men and thirty- nine black men, women, and children lost their lives. Some thought that Introduction p 1 Lumpkins.1-108 6/13/08 4:35 PM Page 2 more white than black people had been killed. And others said that more than nine white people and many more—perhaps up to five hundred— black citizens had perished.1 Scholars generally think of East St. Louis, Illinois, as the site of the first of the major World War I–era urban race riots. -

Learning About White Supremacy: Resources for All Ages

P a g e | 1 of 6 Learning About White Supremacy and How to Talk about It Compiled by Marilyn Saxon-Simurro Learning about White Supremacy and How to Talk About it Resources for All Ages Wondering how to talk with your children, students and/or adult peers about race, racism, and white supremacy? Start here with these resources for children, teens, and adults. Items 1-9 offer resources to help adults communicate with children and teens about race, racism, and white supremacy. They are meant for parents, teachers, and mentors. Items 10-20 include information for adults about the lives of Black people that may not have been known or considered. It is hoped that this list will be used to increase knowledge about, empathy for, and effective allyship with Black people. This list with its many links is not meant for people to read in one sitting. Think of it as a menu from which you can choose one issue at a time. These issues together reveal the definition and subtle perniciousness of systemic racism. 1. Into America with Trymaine Lee Podcast: “Into an American Uprising: Talking to Kids about Racism. June 4, 2020. This 27-minute interview of Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum gives great word-for-word scripts parents, teachers and mentors can use in discussing race. You can listen here https://www.nbcnews.com/podcast/into-america/american- uprising-talking-kids-about-racism-n1225316 or on other podcast platforms such as Stitcher, Spotify, or iTunes. The full transcript is here: https://www.nbcnews.com/podcast/into-america/transcript-talking-kids-about-racism- n1226281. -

From 'Sundown Town'

Goshen, Indiana: From ‘Sundown Town’ in 20th Century to ‘Resolution’ in 21st Century PowerPoint presentation by Dan Shenk at Goshen Art House for Goshen Resilience Guild—October 11, 2018 [Begin PowerPoint video; transcript below by Dan Shenk] Dan Shenk It’s great to be here. And thanks for coming out on this chilly evening. Fall has arrived, after summer just a couple days ago. Lee Roy Berry and I very much appreciate the opportunity to make this joint presentation regarding “sundown towns,” which would be a lamentable legacy of Goshen and thousands of communities across the United States the past 100-plus years—especially the first two-thirds of the 20th century, but still persisting today in some places. Thank you, Phil, for inviting us, and we’re grateful for your creative work with the Resilience Guild. As the program indicates, I’ve titled the PowerPoint presentation “Goshen, Indiana: From ‘Sundown Town’ in 20th Century to ‘Resolution’ in 21st Century.” I put the word “resolution” in quotes, because even though the Goshen City Council took a very significant step 3½ years ago to unanimously pass a resolution acknowledging this aspect of Goshen’s history, we as a community and as individuals are still a work in progress as we seek resolution regarding racial issues. By no means have we arrived. There’s a lot that could be said about sundown towns, so I decided to write out most of my comments in order to focus on the most pertinent. After an interview, Lee Roy and I look forward to questions, discussion and your own stories that you might share with us a bit later. -

Proceedings: Sixth Biennial Conference on Religion and American Culture

Proceedings: Sixth Biennial Conference on Religion and American Culture June 6-9, 2019 The Alexander Hotel Indianapolis, Indiana hosted by The Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture in the IU School of Liberal Arts Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and Religion & American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation Editors Philip Goff Lauren Schmidt Nate Wynne © 2019 The Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Proceedings: Sixth Biennial Conference on Religion and American Culture, June 2019 Table of Contents Introduction Philip Goff, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis 4 Part I Teaching American Religion Kathleen Holscher, University of New Mexico 6 Carolyn M. Jones Medine, University of Georgia 8 Douglas Thompson, Mercer University 12 Translating Scholarship Heath W. Carter, Valparaiso University 15 Robert Orsi, Northwestern University 17 Mira Sucharov, Carleton University 19 Part II Religion and Refugees Melissa Borja, University of Michigan 22 Tricia C. Bruce, University of Notre Dame 25 Gale L. Kenny, Barnard College 27 Different Narratives in Religion and American Politics Prema Kurien, Syracuse University 30 David Harrington Watt, Haverford College 32 Aubrey L. Westfall, Wheaton College 34 Part III Religion and Crisis Amanda J. Baugh, California State University, Northridge 37 John Corrigan, Florida State University 39 Anthony Petro, Boston University 41 New Religious Movements Embodied Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis 44 Leonard Norman Primiano, Cabrini University 46 Judith Weisenfeld, Princeton University 49 Part IV Science, Technology, and Spirituality Sylvester A. Johnson, Virginia Tech 53 Hillary Kaell, Concordia University 55 Christopher White, Vassar College 59 Looking Ahead Rudy V. -

Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) 1 Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) 1 Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also called the Sioux Treaty of 1868) was an agreement between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation[1] signed in 1868 at Fort Laramie in the Wyoming Territory, guaranteeing to the Lakota ownership of the Black Hills, and further land and hunting rights in South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana. The Powder River Country was to be henceforth closed to all whites. The treaty ended Red Cloud's War. In the treaty, as part of the U.S. vendetta to General William T. Sherman (third from left) and Commissioners in Council with "divide and conquer", the U.S. included all chiefs and headmen of different bands of the Sioux, including Arapaho Indians, Ponca lands in the Great Sioux Reservation. Fort Laramie, Wyoming, 1868. Photograph by Alexander Gardner Conflict between the Ponca and the Sioux/Lakota, who now claimed the land as their own by U.S. law, forced the U.S. to remove the Ponca from their own ancestral lands in Nebraska to poor land in Oklahoma. The treaty includes an article intended to "ensure the civilization" of the Lakota, financial incentives for them to farm land and become competitive, and stipulations that minors should be provided with an "English education" at a "mission building." To this end the U.S. government included in the treaty that white teachers, blacksmiths, a farmer, a miller, a carpenter, an engineer and a government agent should take up residence within the reservation. -

California's Former Sundown Towns Face up to Racist Legacies

Humboldt Geographic Volume 2 Article 23 2021 California's Former Sundown Towns Face Up to Racist Legacies Michael Christmas [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/humboldtgeographic Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, and the Spatial Science Commons Recommended Citation Christmas, Michael (2021) "California's Former Sundown Towns Face Up to Racist Legacies," Humboldt Geographic: Vol. 2 , Article 23. Available at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/humboldtgeographic/vol2/iss1/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humboldt Geographic by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christmas: California's Former Sundown Towns Face Up to Racist Legacies Feature Stories California’s Former Sundown Towns Face Up to Racist Legacies Michael Christmas any towns in California and the United States their schools. For instance, Glendale, California, was a Mhave a deep history of racism, segregation, and sundown town with an active Ku Klux Klan and a neo- violence. Sundown towns are majority-white places Nazi group from the 1960s into the 1990s. The California that attempt to keep their towns minority-free through Real Estate Association used to boast that Glendale violence, harassment, or discriminatory legislation. was a “100 percent Caucasian Race Community.” “Sundown towns” refers to the practice of town officials Recently, however, the Glendale City Council voted posting notices that minorities could work and travel unanimously in favor of a resolution that not only in their towns during the day, but must leave by sunset. -

Report on Benton, Illinois, As Sundown Town James W. Loewen

Case 3:10-cv-00995-GPM-DGW Document 60-2 Filed 09/12/12 Page 1 of 12 Page ID #447 Report on Benton, Illinois, as Sundown Town James W. Loewen September 9, 2012 re Harry Huddleston v. City of Alton, et al. Qualifications I hold an M.A. and Ph.D. in sociology from Harvard University, with specialization in race relations. Since graduate school, I have appeared as an expert witness (testifying in court, giving depositions, writing reports, etc.) in fifty to a hundred cases. Many of these were in federal court; many involved civil rights, voting rights, etc. My first two cases, in Wilkinson and Yazoo counties, Mississippi, for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law back in 1968 and 1969, treated overwhelmingly white juries that sat in judgement of African American defendants. My c.v., which I append, lists and describes most of the cases in which I appeared since then, as well as other aspects of my professional life and qualifications. My website, http://sundown.afro.illinois.edu/sundowntowns.php, maintained by the Department of African American Studies at the University of Illinois, is the "go-to" website for researchers of sundown towns across the United States. I would also note that last month the American Sociological Association gave me the Cox-Johnson-Frazier Award "for research, teaching, and service in the tradition" of these three distinguished African American sociologists. Also, kindly note that Sundown Towns was named Outstanding Book for 2005 by the Gustavus Myers Center for the Study of Bigotry and Tolerance. Background on Sundown Towns Many people do not realize that after 1890, race relations worsened across the United States, not just in the South.