February 25, 2021 to Whom It May Concern: Please Find Attached Our Updated Community Impact Assessment of Lambert Compressor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Americans in Our Area

Early Native Americans In Our Area Written & Published by the Waynesboro Historical Commission Founded 1971 Waynesboro, Virginia 22980 Dedication The Historic Commission of Waynesboro dedicates this publication to the earliest settlers of the North American Continent and in particular Virginia and our immediate region. Their relentless push through an unmarked environment exemplifies the quest of the human spirit to reach the horizon and make it its own. Until relatively recently, a history of America would devote a slight section to the Indian tribes discovered by the colonists who landed on the North American continent. The subsequent text would detail the claiming of the land, the creation of towns and villages, and the conquering of the forces that would halt the relentless move to the West. That view of history has been challenged by the work of archeologists who have used the advances in science and the skills of excavation to reveal a past that had been forgotten or deliberatively ignored. This publication seeks to present a concise chronicle of the prehistory of our country and our region with attention to one of the forgotten and marginalized civilizations, the Monacans who existed and prospered in Central Virginia and the areas immediate to Waynesboro. Migration to North America Well before the Romans, the Greeks, or the Egyptians created the culture we call Western Civilization, an ethnic group known as the “First People” began its colonization of the North American continent. There are a number of theories of how the original settlers came to the continent. Some thought they were the “Lost Tribes” of the Old Testament. -

Southern Indian Studies

Southern Indian Studies Volume 40 1991 Southern Indian Studies Published by The North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. 109 East Jones Street Raleigh, NC 27601-2807 Mark A. Mathis, Editor Officers of the Archaeological Society of North Carolina President: J. Kirby Ward, 101 Stourbridge Circle, Cary, NC 27511 Vice President: Richard Terrell, Rt. 5, Box 261, Trinity, NC 27370. Secretary: Vin Steponaitis, Research Laboratories of Anthropology, CB 3120, Alumni Building, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599. Treasurer: E. William Conen, 804 Kingswood Dr., Cary, NC 27513 Editor: Mark A. Mathis, Office of State Archaeology, 109 East Jones St., Raleigh, NC 27601-2807. At-Large Members: Stephen R. Claggett, Office of State Archaeology, 109 East Jones St., Raleigh, NC 27601-2807. R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., Research Laboratories of Anthropology, CB 3120, Alumni Building, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599. Robert Graham, 2140 Graham-Hopedale Rd., Burlington, NC 27215. Loretta Lautzenheiser, 310 Baker St., Tarboro, NC 27886. William D. Moxley, Jr., 2307 Hodges Rd., Kinston, NC 28501. Jack Sheridan, 15 Friar Tuck Lane, Sherwood Forest, Brevard, NC 28712. Information for Subscribers Southern Indian Studies is published once a year in October. Subscription is by membership in the North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. Annual dues are $10.00 for regular members, $25.00 for sustaining members, $5.00 for students, $15.00 for families, $150.00 for life members, $250.00 for corporate members, and $25.00 for institutional subscribers. Members also receive two issues of the North Carolina Archaeological Society Newsletter. Membership requests, dues, subscriptions, changes of address, and back issue orders should be directed to the Secretary. -

8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina

8 Tribes, 1 State: North Carolina’s Native Peoples As of 2014, North Carolina has 8 state and federally recognized Native American tribes. In this lesson, students will study various Native American tribes through a variety of activities, from a PowerPoint led discussion, to a study of Native American art. The lesson culminates with students putting on a Native American Art Show about the 8 recognized tribes. Grade 8 Materials “8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina” PowerPoint, available here: o http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2014/06/NCNativeAmericans1.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode”; upon completion of presentation, hit ESC on your keyboard to exit the file o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] “Native American Art Handouts #1 – 7”, attached North Carolina Native American Tribe handouts, attached o Lumbee o Eastern Band of Cherokee o Coharie o Haliwa-‑ Saponi o Meherrin o Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation o Sappony o Waccamaw Siouan “Create a Native American Art Exhibition” handout, attached “Native Americans in North Carolina Fact Sheet”, attached Brown paper or brown shopping bags (for the culminating project) Graph paper (for the culminating project) Art supplies (markers, colored pencils, crayons, etc. Essential Questions: What was life like for Native Americans before the arrival of Europeans? What happened to most Native American tribes after European arrival? What hardships have Native Americans faced throughout their history? How many state and federally recognized tribes are in North Carolina today? Duration 90 – 120 minutes Teacher Preparation A note about terminology: For this lesson, the descriptions Native American and American Indian are 1 used interchangeably when referring to more than one specific tribe. -

Marion F. Werkheiser, Attorney for the Monacan Indian Nation, (703) 489-6059, [email protected]

THE MONACAN INDIAN NATION URGES YOU TO HELP SAVE RASSAWEK The James River Water Authority (JRWA) plans to build a water pump station on top of Rassawek, the Monacans’ capital city documented by John Smith in his 1612 Map of Virginia (see image). JRWA must move the project to an alternative location so that Rassawek can be saved for future generations and Monacan ancestors can be allowed to rest in peace. • Rassawek was located at the confluence of the Rivanna and James Rivers, and John Smith described it as the capital city to which all other Monacan towns paid tribute. Researchers from the Smithsonian verified the location in the 1880s and again in the 1930s, and the Commonwealth of Virginia has included the Rassawek archaeological site in its files since at least 1980. It is the Monacan equivalent of Werowocomoco, the Powhatan capital now planned to be a national park. • JRWA (a joint venture of Louisa and Fluvanna Counties) proposes to build a pump station to deliver water to help attract economic development, such as prospective breweries and data centers, in Zion Crossroads. JRWA chose the Rassawek site because they thought it would be the least expensive of several options. Building the pump station on top of Rassawek will mean that the site will be obliterated and Monacan burials will likely be disturbed. • Monacan tribal members have participated in several previous repatriation ceremonies previously, and these are somber and traumatizing occasions that the tribe does not enter into lightly or when other options exist. The Monacan Indian Nation has asked the Department of Historic Resources to deny JRWA’s burial permit application and not allow them to dig up Monacan ancestors. -

Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2015 Maopewa iati bi: Takai Tonqyayun Monyton "To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling": Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J. Emrick Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Emrick, Isaac J., "Maopewa iati bi: Takai Tonqyayun Monyton "To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling": Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755" (2015). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5543. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maopewa iati bi: Takai Toñqyayuñ Monyton “To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling”: Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J. Emrick Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Tyler Boulware, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Michele Stephens, Ph.D. Department of History & Amy Hirshman, Ph.D. Department of Sociology and Anthropology Morgantown, West Virginia 2015 Keywords: Native Americans, Indian History, West Virginia History, Colonial North America, Diaspora, Environmental History, Archaeology Copyright 2015 Isaac J. Emrick ABSTRACT Maopewa iati bi: Takai Toñqyayuñ Monyton “To abandon so beautiful a Dwelling”: Indians in the Kanawha-New River Valley, 1500-1755 Isaac J. -

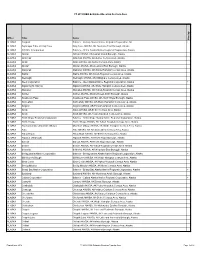

FY 2019 IHBG Estimate Allocation Formula Area

FY 2019 IHBG Estimate Allocation Formula Area Office Tribe Name Overlap ALASKA Afognak Balance - Koniag Alaska Native Regional Corporation, AK + ALASKA Agdaagux Tribe of King Cove King Cove ANVSA, AK-Aleutians East Borough, Alaska ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated Balance - Ahtna Alaska Native Regional Corporation, Alaska ALASKA Akhiok Akhiok ANVSA, AK-Kodiak Island Borough, Alaska ALASKA Akiachak Akiachak ANVSA, AK-Bethel Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Akiak Akiak ANVSA, AK-Bethel Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Akutan Akutan ANVSA, AK-Aleutians East Borough, Alaska ALASKA Alakanuk Alakanuk ANVSA, AK-Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Alatna Alatna ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Aleknagik Aleknagik ANVSA, AK-Dillingham Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Aleut Corporation Balance - Aleut Alaska Native Regional Corporation, Alaska + ALASKA Algaaciq (St. Mary's) Algaaciq ANVSA, AK-Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Allakaket Allakaket ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Ambler Ambler ANVSA, AK-Northwest Arctic Borough, Alaska ALASKA Anaktuvuk Pass Anaktuvuk Pass ANVSA, AK-North Slope Borough, Alaska ALASKA Andreafski Andreafsky ANVSA, AK-Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Angoon Angoon ANVSA, AK-Hoonah-Angoon Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Aniak Aniak ANVSA, AK-Bethel Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Anvik Anvik ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Arctic Slope Regional Corporation Balance - Arctic Slope Alaska Native Regional Corporation, Alaska ALASKA Arctic Village Arctic Village ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk -

Native Pathways to Health Community Report

Native Pathways to Health Community Report November 2020 I. NPTH Purpose, Methods overview The Native Pathways to Health (NPTH) project builds upon existing community- academic partnerships with NC’s AI communities and the University of NC American Indian Center, and seeks to leverage community’s unique strengths to better understand and address tribal health priorities. The tribal communities that partnered (9) in the Native Pathways to Health Project included: Coharie Tribe, Haliwa-Saponi Tribe, Lumbee Tribe of NC, Meherrin Tribe, Metrolina Native American Society, Occaneechi Band of Saponi Nation, Triangle Native American Society, Sappony Tribe, and Waccamaw-Siouan Tribe. In Year 1, the NPTH research team, which includes well-respected members of NC’s AI tribes, partnered with adults and youth from NC tribes and urban Indian organizations to form a Tribal Health Ambassador Program. Tribal Health Ambassadors (THAs) collaborated with the research team to assess health in their communities: Adult THAs led talking circles (a sacred approach for engaging in discussion). Talking Circles are a traditional way for AI people to solve problems by effectively removing barriers which allows them to express themselves with complete freedom in a sacred space. Normally the circle is blessed by an Elder. Important to remember what is said in the circle stays within the circle but an exception will be made for this project so we can help tell the stories of the needs within the communities and also use this data to create a health assessment tailored to each tribal community. Youth THAs designed projects following a Youth Participatory Action Research approach. -

WE HAVE a STORY to TELL the Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region

A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS GRADES 9-12 I-AR T!PLESI PEACE Onwun The Mull S..1M• ...i Migb<y PIUNC,'11. 8'*'C,,...fllc:-..I. ltJosolf oclW,S."'-', fr-•U>d lrti..I. n.<.odnJll>. f.O,ctr. l11iiiJ11 lCingJ... and - Queens, c!re. ("', L l.r.Jdic t~'ll~~ti.flf-9, 16-'"'. DEDICATION Group of Chickahominy Indians at the Chickahominy River, Virginia, 1918. Photo by Frank G. Speck. For the Native Americans of the Chesapeake region—past, present, and future. We honor your strength and endurance. Thank you for welcoming us to your Native place. Education Office of the National Museum of the American Indian Acknowledgments Coauthors, Researchers: Gabrielle Tayac, Ph.D. (Piscataway), Edwin Schupman (Muscogee) Contributing Writer: Genevieve Simermeyer (Osage) Editor: Mark Hirsch Reviewers: Leslie Logan (Seneca), Clare Cuddy, Kakwireiosta Hall (Cherokee/Mohawk), Benjamin Norman (Pamunkey) Additional Research: Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, Ph.D., Buck Woodard (Lower Muscogee Creek), Angela Daniel, Andy Boyd Design: Groff Creative Inc. Special Thanks: Helen Scheirbeck, Ph.D. (Lumbee); Sequoyah Simermeyer (Coharie), National Congress of American Indians; NMAI Photo Services All illustrations and text © 2006 NMAI, Smithsonian Institution, unless otherwise noted. TABLE OF CONTENTS WE HAVE A STORY TO TELL The Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region Introduction for Teachers Overview/Background, Acknowledgments, Pronunciation of Tribal Names . 2 Lesson Plan. 3 Lesson Questions . 5 Reading Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region and the Enduring Effects of Colonialism . 6 SMALL GROUP PROJECT AND CLASS PRESENTATION Issues of Survival for Native Communities of the Chesapeake Region Instructions for Small Group Project . 15 Readings, Study Questions, Primary Resources, and Secondary Resources Issue 1: The Effects of Treaty Making . -

Federal Funding for Non-Federally Recognized Tribes

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Honorable Dan Boren, GAO House of Representatives April 2012 INDIAN ISSUES Federal Funding for Non-Federally Recognized Tribes GAO-12-348 April 2012 INDIAN ISSUES Federal Funding for Non-Federally Recognized Tribes Highlights of GAO-12-348, a report to the Honorable Dan Boren, House of Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found As of January 3, 2012, the United Of the approximately 400 non-federally recognized tribes that GAO identified, States recognized 566 Indian tribes. 26 received funding from 24 federal programs during fiscal years 2007 through Federal recognition confers specific 2010. Most of the 26 non-federally recognized tribes were eligible to receive this legal status on tribes and imposes funding either because of their status as nonprofit organizations or state- certain responsibilities on the federal recognized tribes. Similarly, most of the 24 federal programs that awarded government, such as an obligation to funding to non-federally recognized tribes during the 4-year period were provide certain benefits to tribes and authorized to fund nonprofit organizations or state-recognized tribes. In addition, their members. Some tribes are not some of these programs were authorized to fund other entities, such as tribal federally recognized but have qualified communities or community development financial institutions. for and received federal funding. Some of these non-federally recognized For fiscal years 2007 through 2010, 24 federal programs awarded more than tribes are state recognized and may be $100 million to the 26 non-federally recognized tribes. Most of the funding was located on state reservations. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 79/Tuesday, April 27, 2021/Notices

22258 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 79 / Tuesday, April 27, 2021 / Notices members of the Pawnee Nation of burials but without any further DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oklahoma. attributions. Human skeletal remains In 1940, 321 cultural items were and associated funerary objects from National Park Service removed from cemeteries associated this site were repatriated to the Pawnee [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0031769; with the Clarks site (25PK1) in Polk Nation of Oklahoma in 1990–1991. The PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] County, NE. These objects were four unassociated funerary objects are recovered during archeological three soil samples and one flintlock Notice of Inventory Completion: excavations by the Nebraska State rifle. Valentine Museum, Richmond, VA Historical Society. The 321 objects are listed as having been recovered from This village was occupied by the AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. burials but without any further Kitkahaki Band of the Pawnee from ACTION: Notice. attributions. Human skeletal remains about 1775 to 1809, based on and associated funerary objects from archeological and ethnohistorical SUMMARY: The Valentine Museum has this site were repatriated to the Pawnee information, as well as oral traditional completed an inventory of human Nation of Oklahoma in 1990–1991. The information provided by members of the remains and associated funerary objects, 321 unassociated funerary objects are: Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. in consultation with the appropriate 15 brass/copper bells, one brass/copper Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian ornament, one bridle bit, two bullet Determinations Made by History organizations, and has determined that molds, five chalk fragments, four Nebraska there is a cultural affiliation between the human remains and associated funerary chipped stone flakes, five chipped stone Officials of History Nebraska have tools, two clasp knives, three clay objects and present-day Indian Tribes or determined that: lumps, three cloth and leather Native Hawaiian organizations. -

S. 691 [Report No

II Calendar No. 161 115TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. 691 [Report No. 115–123] To extend Federal recognition to the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Chicka- hominy Indian Tribe—Eastern Division, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, Inc., the Monacan Indian Nation, and the Nansemond Indian Tribe. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES MARCH 21, 2017 Mr. KAINE (for himself and Mr. WARNER) introduced the following bill; which was read twice and referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs JUNE 28, 2017 Reported by Mr. HOEVEN, without amendment A BILL To extend Federal recognition to the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Chickahominy Indian Tribe—Eastern Divi- sion, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, Inc., the Monacan Indian Nation, and the Nansemond Indian Tribe. 1 Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representa- 2 tives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, VerDate Sep 11 2014 23:46 Jun 28, 2017 Jkt 069200 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6652 Sfmt 6201 E:\BILLS\S691.RS S691 rfrederick on DSK3GLQ082PROD with BILLS 2 1 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. 2 (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the 3 ‘‘Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal 4 Recognition Act of 2017’’. 5 (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents of 6 this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. TITLE I—CHICKAHOMINY INDIAN TRIBE Sec. 101. Findings. Sec. 102. Definitions. Sec. 103. Federal recognition. Sec. 104. Membership; governing documents. -

The Virginia Indians Meet the Tribes Student Activity Book

The Virginia Indians Meet the Tribes http://virginiaindians.pwnet.org/history/modern_indians.php Student Activity Book Virginia Department of Education © 2013 Table of Contents Introduction………..…………………..…………...1 Virginia’s First People: 1607………………………2 Adaptations & Occupations: 1607…………….3 Adaptations & Occupations: Today…………..4 The Virginia Indian Pow Wow……………………6 Regalia………………………………………………7 Similarities & Differences………………….……..8 Tech it Up: Find out More!………………………..9 Introduction European colonists arriving in Virginia may have been greeted with, "Wingapo." Indians have lived in what is now called Virginia for thousands of years. While we are still learning about the people who inhabited this land, it is clear that Virginia history did not begin in 1607. If you ask any Virginia Indian, "When did you come to this land?" he or she will tell you, "We have always been here." http://virginiaindians.pwnet.org/history/index.php 1 Virginia’s First People http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/arch_NET/timeline/late_wood_map.htm There were three major language families at the time of European contact in 1607: the Siouan, the Algonquian, and the Iroquoian. In the video, Keenan taught us that today, there are eleven different Virginia Indian tribes recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia. This activity book will give you the opportunity to compare Virginia’s first people from 1607 to Virginia’s first people today. You will also be able to compare your own life and traditions to those of a Virginia Indian child today. 2 Adaptations & Occupations: 1607 Directions: Draw and label pictures that show how Virginia’s first people adapted to their environment and what kinds of occupations they had in 1607.