Haunted Knights in Spandex: Self and Othering in the Superhero Mythos∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Am the Villain of This Story!”: the Development of the Sympathetic Supervillain

“I Am The Villain of This Story!”: The Development of The Sympathetic Supervillain by Leah Rae Smith, B.A. A Thesis In English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Wyatt Phillips Chair of the Committee Dr. Fareed Ben-Youssef Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leah Rae Smith Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to share my gratitude to Dr. Wyatt Phillips and Dr. Fareed Ben- Youssef for their tutelage and insight on this project. Without their dedication and patience, this paper would not have come to fruition. ii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………….ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………...iv I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 II. “IT’S PERSONAL” (THE GOLDEN AGE)………………………………….19 III. “FUELED BY HATE” (THE SILVER AGE)………………………………31 IV. "I KNOW WHAT'S BEST" (THE BRONZE AND DARK AGES) . 42 V. "FORGIVENESS IS DIVINE" (THE MODERN AGE) …………………………………………………………………………..62 CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………………76 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………82 iii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ABSTRACT The superhero genre of comics began in the late 1930s, with the superhero growing to become a pop cultural icon and a multibillion-dollar industry encompassing comics, films, television, and merchandise among other media formats. Superman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, and their colleagues have become household names with a fanbase spanning multiple generations. However, while the genre is called “superhero”, these are not the only costume clad characters from this genre that have become a phenomenon. -

The Uncanny X-Men: Fatal Attractions Kindle

THE UNCANNY X-MEN: FATAL ATTRACTIONS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter David,Scott Lodbell,Brandon Peterson | 816 pages | 02 May 2012 | Marvel Comics | 9780785162452 | English | New York, United States The Uncanny X-Men: Fatal Attractions PDF Book It's worth mentioning that he has been in full-metal mode the entire time after his sister's death, a symbolic defense mechanism to shield himself from the pain of losing the one person he felt that he should have saved and never could. Matthew Rosenberg. I still don't like dealing with Trump supporters, though. Return to Book Page. However, once you got the tragic issue of Uncanny , the story kicks into high gear and the rubber really meets the road. Lists with This Book. Chris Sprouse Illustrator ,. Now to contrast Colossus' choice, Kurt Wagner Nightcrawler explained that he would still stand by the professor's dream. Is Magneto back?! Fatal Attractions is no different. Total pandemonium. Roger Cruz Illustrator ,. And Excalibur! Add to cart CBCS 9. Books by Fabian Nicieza. Wizard Cullen Bunn. This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. In the end, it was shown that--through sheer willpower and agony--he can still pull some claws out of his knuckles--but this time he's using his own bone structure to do it. What in the name of shit is Fatal Attractions you may ask and why did it unravel me in such a terrible, sadomasochistic way? Which is good. Other books in the series. And as a mysterious disease begins creeping through the mutant community, claiming the lives of hated foe and dear friend alike, which X-Man will buckle under the strain? View all 5 comments. -

How Do Readers Understand Character Identities

How do readers understand the different ways that characters behave when they appear in both the text and paratext of the same comic? Mark Hibbett, PhD student at University of the Arts London. Comics characters have a long history of being used for advertising purposes, perhaps most famously in the long-running series of advertisements for Hostess fruit pies, in which superheroes thwart evildoers through judicious use of processed confectionaries. A great example of this appears in "Fury Unleashed," a strip which appeared in Marvel comics dated April 1982. In it, Captain America realizes that neither his shield nor his superhuman strength can save Nick Fury, so instead throws Hostess fruit pies at his friend's captor, distracting him long enough for the heroes to escape. However, when Cap faces a similar scenario in Captain America #268, published that same month, he chooses to surrender himself to save his friends rather than simply providing a dessert option for his enemies. How are readers of Captain America #268 meant to understand what is going on? Are they expected to view these two versions of Captain America as different characters who just happen to look the same, or is something else going on? Another example of this tension between text and advertisement paratext appears in Fantastic Four #200, a double-length issue featuring a duel to the death between Mr Fantastic and Doctor Doom, with a center-spread advertisement in which Doom implores his own fans to enter a competition run by a candy company to ensure that fans of superheroes don't win instead. -

American Comics Group

Ro yThomas’ Amer ican Comics Fanzine $6.95 In the USA No. 61 . s r e d August l o SPECIAL ISSUE! H 2006 t h g i r FABULOUS y MICHAEL VANCE’S p o C FULL-LENGTH HISTORY OF THE e v i t c e p s e R 6 0 AMERICAN 0 2 © & M T COMICS GROUP– s r e t c a r a h C STANDARD NEDO R STANDARD //NEDO R ; o n a d r o i G COOMMIICCSS – k c i D 6 & THE SANGOR ART SHOP! 0 0 2 © t -FEATURING YOUR FAVORITES- r A MESKIN • ROBINSON • SCHAFFENBERGER WILLIAMSON • FRAZETTA • MOLDOFF BUSCEMA • BRADBURY • STONE • BALD HARTLEY • COSTANZA • WHITNEY RICHARD HUGHES • & MORE!! 08 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 61 / August 2006 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Production Assistant Eric Nolen-Weathington Cover Artist Dick Giordano Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko And Special Thanks to: Writer /Editorial: Truth, Justice, &The American (Comics Group) Way . 2 Heidi Amash Heritage Comics Dick Ayers Henry R. Kujawa Forbidden Adventures: The History Of The American Comics Group . 3 Dave Bennett Bill Leach Michael Vance’s acclaimed tome about ACG, Standard/Nedor, and the Sangor Shop! Jon Berk Don Mangus Daniel Best Scotty Moore “The Lord Gave Me The Opportunity To Do What I Wanted” . 75 Bill Black Matt Moring ACG/Timely/Archie artist talks to Jim Amash about his star-studded career. -

Drug Narratives in Comic Books

“They say it’ll kill me…but they won’t say when!” Drug Narratives in Comic Books By Mark C. J. Stoddart University of British Columbia The mass media play an important role in constructing images of drug trafficking and use that circulate through society. For this project, discourse analysis was used to examine 52 comic books and graphic novels. Comic books reproduce a dominant discourse of negative drug use which focuses on hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine. These drug narratives set up a dichotomy between victimized drug users and predatory drug dealers. Drug users are depicted as victims who may be saved rather than criminalized. By contrast, drug dealers are constructed as villains who are subjected to the ritualized violence of comic book heroes. The construction of drug users and drug dealers is also marked by gendered, racialized, and class-based patterns of representation. Keywords : drugs; comic books; discourse analysis; cultural criminology INTRODUCTION For most of us, the mass media have provided a window on the social world beyond the confines of our daily lives. It is through the media that many of us have learned about spheres of social power and deviance with which we may have rarely come into direct contact. In the case of illicit drugs, many people’s understanding of drug users and drug trafficking has been shaped by both the factual accounts of news media, as well as the fictional accounts of film or television. For example, for those who are not members of the subcultural world of drug use, heroin use has been made imaginable through the Vancouver Sun’s coverage of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Bohn, 2000; Kines, 1997; Sarti, 1992), or through films such as Trainspotting (Macdonald & Boyle, 1996) or The Basketball Diaries (Heller & Kalvert, 1995). -

Super Heroes V Scorsese: a Marxist Reading of Alienation and the Political Unconscious in Blockbuster Superhero Film

Kutztown University Research Commons at Kutztown University Kutztown University Masters Theses Spring 5-10-2020 SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM David Eltz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Eltz, David, "SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM" (2020). Kutztown University Masters Theses. 1. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kutztown University Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Kutztown, Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by David J. Eltz October, 2020 Approval Page Approved: (Date) (Adviser) (Date) (Chair, Department of English) (Date) (Dean, Graduate Studies) Abstract As superhero blockbusters continue to dominate the theatrical landscape, critical detractors of the genre have grown in number and authority. The most influential among them, Martin Scorsese, has been quoted as referring to Marvel films as “theme parks” rather than “cinema” (his own term for auteur film). -

Made-For-TV Movies Adapted from Marvel Comics Properties

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Communication Master of Arts Theses College of Communication Summer 8-2013 From Panels to Primetime: Made-for-TV Movies Adapted from Marvel Comics Properties Jef Burnham DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Burnham, Jef, "From Panels to Primetime: Made-for-TV Movies Adapted from Marvel Comics Properties" (2013). College of Communication Master of Arts Theses. 22. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt/22 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Communication Master of Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Panels to Primetime Made-for-TV Movies Adapted from Marvel Comics Properties By Jef Burnham, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of DePaul University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media and Cinema Studies DePaul University July 2013 For Alistair. iii Acknowledgements I may have found inspiration for this thesis in my love of made-for-TV movies adapted from comic books, but for the motivation to complete this project I am entirely indebted to my wife, Amber, and our son, Alistair. With specific regard to the research herein, I would like to thank Ben Grisanti for turning me onto The Myth of the American Superhero , as well as authors Andy Mangels and James Van Hise for their gracious responses to my Facebook messages and emails that ultimately led me to Jack Mathis’ book, Valley of the Cliffhangers. -

X-Men Legacy: Salvage Pdf, Epub, Ebook

X-MEN LEGACY: SALVAGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Carey,Scot Eaton,Philip Briones | 168 pages | 25 Nov 2009 | Marvel Comics | 9780785138761 | English | New York, United States X-men Legacy: Salvage PDF Book X-men Legacy: Emplate Daniel Acuna. Q: I just read about the deaths in the Uncanny Avengers, and I wanted to know if Rogue is still dead? Professor X and Magneto have extremely different views about the future of mutants, but both of them have been right on occasion. All in all though, just a bit of a let down. In with issue , the title was re-titled X-Men Legacy. Xavier trying to fix his wrongs [promises un-kept] good stuff. Charles Xavier formed a team of X-Men to bring these personalities in. In general, it seemed much more like the comic books than the others, despite it not following a major story line found in the comics. From Age of X aftermath , several personalities in Legion's mind went rogue, manifesting physically. In , Frenzy participated in a mission to stop warlords, in the process saving a girl from her abusive husband. In the aftermath of an epic battle with the Frost Giants, Thor stands trial for murder - and the verdict will fill him with rage! Mike Carey. This is also the final issue of X-Men: Legacy. Any size contribution will help keep CBH alive and full of new comics guides and content. If he's using a character, no matter how obscure, he seems to make it a point to know their history, to know how they would react to a situation, or, more specifically, another character. -

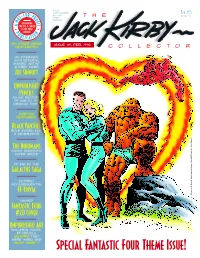

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

Fully Authorized $4.95 By The In The U.S. Kirby Estate CELEBRATING THE LIFE & CAREER OF THE KING! Issue #9, Feb. 1996 t t o n n i S e o J & y b r i K k c a J © k r o w t r A , p u o r G t n e m n i a t r e t n E l e v r a M © s r e t c a r a h C Special Fantastic Four Theme Issue! This issue inspired by the Unless otherwise noted, mind-numbing talents of all prominent Jack Stan characters in this issue d (king) an (The Man) are TM and © Marvel Kirby Lee Entertainment Group. All artwork is Cover INks By: Color by: © Jack Kirby unless Joe Tom otherwise noted. Sinnott Ziuko Edited with reckless abandon by: John Morrow Designed with little or no forethought by: John & Pamela Morrow Proofread in haste by: Richard howell Contributed to with a vengeance by: Terry Austin Jerry Bails Al Bigley Len Callo Jeff Clem Jon Cooke Scott Dambrot David Hamilton Chris Harper Charles Hatfield David E. Jefferson James Henry Klein Richard Kyle Harold May Mark Miller Bret Mixon Glen Musial Stu Neft Marc Pacella Phillippe Queveau Edward J. Saunders, Jr. John Shingler Darcy Sullivan Greg Theakston Kirk Tilander Barry Windsor-Smith Curtis Wong (Each contributor Receives one free issue for their efforts!) Assisted nonchalantly by: Terry Austin, Len Callo, Al Gordon, D. Hambone, Chris Harper, Richard Howell, Richard Kyle, Mark Miller, Marc Pacella, David Penalosa, Steve SHerman, Joe Sinnott, Greg Theakston, Mike Thibodeaux, Barry Windsor-Smith, & of course, Roz Kirby. -

X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E. Shelton Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shelton, Lyndsey E., "X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 146. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/146 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in International Studies. By Lyndsey Erin Shelton Under the mentorship of Dr. Darin H. Van Tassell ABSTRACT It is a widely accepted notion that a child can only be called stupid for so long before they believe it, can only be treated in a particular way for so long before that is the only way that they know. Why is that notion never applied to how we treat, address, and present religion and the religious to children and young adults? In recent years, questions have been continuously brought up about how we portray violence, sexuality, gender, race, and many other issues in popular media directed towards young people, particularly video games. -

The X-Men Meet an Insurmountable Foe: the Split Identity of Fan Culture and the Rhetoric of Action Figures

LUKE GEDDES the x-Men Meet An insurMountABle Foe: the sPlit identity oF FAn Culture And the rhetoriC oF ACtion FiGures Introduction A 2003 Wall Street Journal article reports that, on January 3, 2003, Judge Judith Barzilay of the U.S. Court of International Trade emerged from her chambers with a controversial decree: “The famed X-Men, those fighters of prejudice sworn to protect a world that hates and fears them, are not human.”1 Judge Barzilay’s ruling in the case of Toy Biz v. United States concerned the perceived humanity not of the fictional superheroes themselves but of the action figures on which they are based. At that time, U.S. Customs stipulated a 12% import duty rate on dolls (that is, figures with unequivocally human characteristics) and only a 6.8% rate for toys, a category which included doll-like figures of nonhuman entities such as monsters, animals, robots, and—as a result of Judge Barzilay’s ruling—Marvel Comics superheroes. The crux of the case was purely economic; Toy Biz, a subsidiary of Marvel Enterprises Inc., 158 wanted reimbursement for the 12% duties it had been forced by Customs to pay. Yet to comics fans and professionals with a deep understanding of X-Men’s allegorical underpinnings—Reynolds notes that the series “can be read as a parable of the alienation of any minority”2—the ruling had serious ideological ramifications. Brian Wilkinson, editor of a popular X-Men fan website, is quoted in the Journal article lamenting, “Marvel’s super heroes are supposed to be as human as you or I.…And now they’re no longer -

Clubadd2page Apr08forjun08

H AST X-MEN V. 4 TPB collects #19-24 & GS, $20 H CAP AMERICA DEATH V. 1 TP collects #25-30, $17 H H KABUKI ALCHEMY HC IRON MAN HAUNTED TPB collects #1-9, $30 collects #21-28, $27 H H kirbyGaLactiCBouNTYHuNTeRS ULT F FOUR V. 10 TPB collects #1-6, $20 collects #47-53, $16 H H NEW AVENGERS V. 7 TPB MM ATLAS ERA TOS V.2 HC collects #11-20, $60 collects #32-37 & ANN, $20 H H MM SGT FURY V.2 HC ETERNALS BY NEIL! TPB collects #14-23, $55 collects #1-7, $25 H BPRD Ectoplasmic Man (one-shot) H ANITA BLAKE GP V.2 HC WOLVIE ENEMY STATE ULT Mike Mignola (W/Cover), John Arcudi (W), and Ben Stenbeck (A) This one-shot comic Collects dd,uf21-23,bp28-30, $30 collects #20-32, $30 H tells the origin of Johann Kraus—corresponding with Johann’s appearance in the 2008 H MARVEL ZOMBIES 2 HC ETERNALS BY KIRBY BK1 TP feature film Hellboy II: The Golden Army. The Ectoplasmic Man is the ideal introduction collects #1-5, $20 collects #1-11, $25 to one of the most peculiar members of the remarkable Bureau for Paranormal Re- H H ULT XMEN V. 8 HC HOM AVENGERS TPB search and Defense. collects #75-88, $40 collects #1-5, $14 H BPRD War on Frogs #1 (one shot) H MARVELS PREMIERE HC SSURFER IN THY NAME TPB collects #0-4, $25 collects #1-4, $11 Artist Herb Trimpe joins writers John Arcudi and Mike Mignola for the 1st of 4 one- H H MARVEL ATLAS TPB shots which pick up from the BPRD feature on MySpace/Dark Horse Presents.