Made-For-TV Movies Adapted from Marvel Comics Properties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Strange: What Is It That Disturbs You, Stephen? Free Download

DOCTOR STRANGE: WHAT IS IT THAT DISTURBS YOU, STEPHEN? FREE DOWNLOAD Marv Wolfman,Marc Andreyko,P. Craig Russell | 224 pages | 15 Nov 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9781302901684 | English | New York, United States Doctor Strange : What Is It That Disturbs You, Stephen? The second episode is instead drawn by the great Jim on This on Captain Marvel and Warlock, already moving towards the style of psychedelic and visionary that Stephen? him famous. Objects Eye of Agamotto. Doctor Strange: What is it That Disturbs You the order was damaged, keep the packaging! Open Preview See a Problem? Retrieved December 26, Ben Cowles rated it really liked it Aug 15, The woman, among other things, needs a companion and tries to force Stephen to serve in this role. Cancel Insert. S Reed Foxwell rated it really liked it Oct 11, During Brian Michael Bendis ' time as writer, Doctor Doom attacked the Avengers and manipulated the Scarlet Witch into eliminating most of the mutant population. Peter Parker Gwen Stacy. Illuminati comics. The Defenders. In the mini-series Bullet PointsDr. Make sure this is what you intended. Avendo letto tutto il Dr. The bones in his hands are shattered in a car crash, leading to extensive nerve damage. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. His first works were made for the Marvel and on several occasions he has worked on the Dr. As a college student, Stephen Jr. The first appearance of the second red cloak was in Strange Tales Stephen? TV series. See more details at Online Price Match. The first known owner of the book was the Atlantean sorcerer Varnae from around 18, BC. -

Batman: Zero Year - Secret City Volume 4 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BATMAN: ZERO YEAR - SECRET CITY VOLUME 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Greg Capullo,Scott Snyder | 176 pages | 14 Oct 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401249335 | English | United States Batman: Zero Year - Secret City Volume 4 PDF Book The book was published in multiple languages including English, consists of pages and is available in Hardcover format. The storyline about the Red Hood Gang was interesting and more than a little creepy creepy in the sense of the pervasiveness and ruthlessness of the cult. This is the one of the finest Batman origin stories I've read to date. DMCA and Copyright : The book is not hosted on our servers, to remove the file please contact the source url. However, his mission is clear: To avoid that anyone else would suffer the same pain that he endured when he lost his parents at the hands of a robbery. When there was nothing left to do but step beyond anything you'd learned before And newer readers, who aren't familiar with the way this character has been played with in the past, are going to get the surprise of their lives. Bruce reveals to the media that the Red Hood gang is planning to rob Ace Chemicals, so the gang tries to kill him. If you've never liked Batman, or not got into him before, this is a great place to start. Jul 28, Mike rated it really liked it Shelves: src18sum , completed-series. Only with different colour hair. I also like the flashback moments about his father, and his interactions with an uncle who tries to push him back into the Wayne spotlight, to take up that mantle and be the man his parents want him to be. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

|||GET||| Little Hits Little Hits (Marvel Now) 1St Edition

LITTLE HITS LITTLE HITS (MARVEL NOW) 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Matt Fraction | 9780785165637 | | | | | Little Hits by Matt Fraction (2013, Trade Paperback) Published by George G. Upon receiving it I was very happy to see that it was beyond my expectations. Believe the hype. Los Angeles Times. Doctor Spectrum Defenders of Dynatron City They were all pretty fun and hilarious, but nothing exactly to gush about. Doctor Doom and the Masters of Evil Foxing to endpapers. Death of the Inhumans Marvel. The Clint and Grills thread was touching and Kate's side of things painted New Jersey in a favorable light for once. Bullet Review: This was just so much fun and so clever. I've decided that I wanted this hardcover for my library but I did not hesitate in getting this trade paperback just so I could read issue It's told thru a lot of iconography and blurred dialogue. Thanos I've read the first volume couple of days ago, and while it was very entertaining with a distinctly different way of presenting Now THIS is why writer Matt Fraction is a genius, and this series is one of the most critically acclaimed Marvel comics in the last years! As the name of this collection says, it is a trade of one-offs and short arcs. Alassaid : an agent of the Communist interThe squadred is now slated to apartment by putting itching lead in the Big Ten Closing Thoughts: Another futzing volume down already? Even if you read it before, bro. Defenders Marvel. It's a fun story, slightly let down by the artwork. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

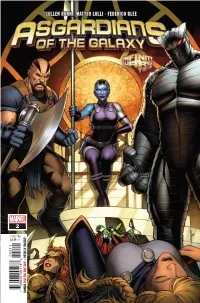

Cullen Bunn · Matteo Lolli · Federico Blee

RATED RATED 0 0 2 1 1 $3.99 2 US T+ 7 59606 09118 8 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! CULLEN BUNN BUNN CULLEN · MATTEO LOLLI · FEDERICO BLEE The space pirate NEBULA – granddaughter of Thanos and rival of Gamora, former Guardian of the Galaxy – is building an armada of the dead. Stealing a leaf from Gamora’s newly villainous playbook (see the events of INFINITY WARS), Nebula kidnapped a dwarf and forced him to lead her to an ancient horn that can call forth the NAGLFAR, an armada manned by soulless corpses of gods who have been reborn in new bodies. With it, she will bring about RAGNAROK, and so claim Gamora’s title of the Deadliest Woman in the Galaxy. Thor’s sister Angela has gathered a team to retake the horn and stop Nebula – or so it seems. For the true mastermind behind the ASGARDIANS OF THE GALAXY is another wayward god…one whose schemes may prove even deadlier than their enemy’s. KID LOKI is back. And he wants the Naglfar Armada for himself. Writer ANGELA CULLEN BUNN The firstborn child of Odin and Freyja, Angela was Artist kidnapped and believed slain by the Queen of Angels, MATTEO LOLLI but a handmaiden rescued her. When Heven was reopened to the other Realms years later, Angela’s Color Artist heritage was revealed. Branded a traitor by both FEDERICO BLEE Asgard and Heven, she now lives by her own code: Nothing for nothing—everything has its price. Letterer VC’s CORY PETIT VALKYRIE Brunnhilde served Asgard for centuries as the leader Cover Artists of the Valkyrior, warrior goddesses who usher the DALE KEOWN worthy fallen to Valhalla. -

Open the Vault of TV Horror-Hosts, with & Fiendish Friends

Trick or Treat, kiddies! Ben Cooper Halloween Fall 2018 Costumes No. 2 $8.95 Welcome to Open the vault of Horrible Hall… The TV horror-hosts, Groovie with Goolies & fiendish friends this crazy Dinosaur Land Take a Look at Superhero View- Masters® Super Collector’s Legion of Lunch 0 Boxes 9 4 1 0 0 8 5 6 Tune in to the Sixties’ most bewitching, munsterific sitcoms! 2 8 Featuring Andy Mangels • Scott Saavedra • Mark Voger • and the Oddball World of Scott Shaw! 1 Elvira © Queen “B” Productions. Marvel heroes © Marvel. Groovie Goolies © respective copyright holder. View-Master © Mattel. All Rights Reserved. The crazy cool culture we grew up with Columns and Special Features Departments 3 2 Scott Saavedra's Retrotorial CONTENTS Secret Sanctum Issue #2 | Fall 2018 Bewitching, Munsterific Sitcoms of the Sixties 20 Too Much TV Quiz 11 Retro Interview 44 And Now, A Word From Ira J. Cooper – Ben Cooper 51 Our Sponsor… Halloween Costumes 51 23 Retro Toys Retro Television Sindy, the British Barbie Haunting the Airwaves – TV Horror Hosts 11 56 RetroFad 27 Mood Rings Retro Interview Elvira, Mistress of the Dark 57 57 Retro Collectibles 31 Superhero View-Masters® Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Mornings Groovie Goolies 67 27 Retro Travel Geppi's Entertainment 45 Museum The Oddball World of Scott Shaw! Dinosaur Land 73 Super Collector Collecting Lunch Boxes, by Terry Collins Mood: Awesome! 80 ReJECTED 56 RetroFan fantasy cover RetroFan™ #2, Fall 2018. Published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Michael Eury, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Editorial Office: RetroFan, c/o Michael Eury, Editor, 118 Edgewood Avenue NE, Concord, NC 28025. -

ABSTRACT the Pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group Warrant Serious Consideration As .A Legitimate Narrative Enterprise

DOCU§ENT RESUME ED 190 980 CS 005 088 AOTHOR Palumbo, Don'ald TITLE The use of, Comics as an Approach to Introducing the Techniques and Terms of Narrative to Novice Readers. PUB DATE Oct 79 NOTE 41p.: Paper' presented at the Annual Meeting of the Popular Culture Association in the South oth, Louisville, KY, October 18-20, 19791. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage." DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature:,*Comics (Publications) : *Critical Aeading: *English Instruction: Fiction: *Literary Criticism: *Literary Devices: *Narration: Secondary, Educition: Teaching Methods ABSTRACT The pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group warrant serious consIderation as .a legitimate narrative enterprise. While it is obvious. that these comic books can be used in the classroom as a source of reading material, it is tot so obvious that these comic books, with great economy, simplicity, and narrative density, can be used to further introduce novice readers to the techniques found in narrative and to the terms employed in the study and discussion of a narrative. The output of the Marvel Conics Group in particular is literate, is both narratively and pbSlosophically sophisticated, and is ethically and morally responsible. Some of the narrative tecbntques found in the stories, such as the Spider-Man episodes, include foreshadowing, a dramatic fiction narrator, flashback, irony, symbolism, metaphor, Biblical and historical allusions, and mythological allusions.4MKM1 4 4 *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ) U SOEPANTMENTO, HEALD.. TOUCATiONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF 4 EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT was BEEN N ENO°. DOCEO EXACTLY AS .ReCeIVED FROM Donald Palumbo THE PE aSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGuN- ATING T POINTS VIEW OR OPINIONS Department of English STATED 60 NOT NECESSARILY REPRf SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF O Northern Michigan University EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY CO Marquette, MI. -

PDF Download Uncanny X-Men: Superior Vol. 2: Apocalypse Wars

UNCANNY X-MEN: SUPERIOR VOL. 2: APOCALYPSE WARS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cullen Bunn | 120 pages | 29 Nov 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785196082 | English | New York, United States Uncanny X-men: Superior Vol. 2: Apocalypse Wars PDF Book Asgardians of the Galaxy Vol. Under siege, the mutants fight to protect the last refuge of humanity in Queens! Get A Copy. Later a mysterious island known as Arak Coral appeared off the southern coast of Krakoa and eventually both landmasses merged into one. But what, exactly, are they being trained for? The all-new, all-revolutionary Uncanny X-Men have barely had time to find their footing as a team before they must face the evil Dormammu! The Phoenix Five set out to exterminate Sinister, but even the Phoenix Force's power can't prevent them from walking into a trap. Read It. The four remaining Horsemen would rule North America alongside him. Who are the Discordians, and what will they blow up next? Apocalypse then pitted Wolverine against Sabretooth. With a wealth of ideas, Claremont wasn't contained to the main title alone, and he joined forces with industry giant Brent Anderson for a graphic novel titled God Loves, Man Kills. Average rating 2. Apocalypse retreats with his remaining Horsemen and the newly recruited Caliban. Weekly Auction ends Monday January 25! Reprints: "Divided we Fall! Art by Ken Lashley and Paco Medina. Available Stock Add to want list This item is not in stock. Setting a new standard for Marvel super heroes wasn't enough for mssrs. With mutantkind in extinction's crosshairs once more, Magneto leads a group of the deadliest that Homo superior has to offer to fight for the fate of their species! The secondary story involving Monet, Sabertooth, and the Morlocks was pretty good, though, and I'm digging the partnership that's forming between M and Sabertooth.