Debates in Transgender, Queer, and Feminist Theory Contested Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unconscionable and Unconstitutional: Bill C-8'S Attempt to Dictate Choices Concerning Sexuality and Gender

Unconscionable and Unconstitutional Bill C-8’s Attempt to Dictate Choices Concerning Sexuality and Gender May 12, 2020 Marty Moore, JD, and Jocelyn Gerke, BComm, MPP, JD (Student-at-Law) Mail: #253, 7620 Elbow Drive SW, Calgary, AB • T2V 1K2 Web: www.jccf.ca • Email: [email protected] • Phone: (403) 475-3622 CRA registered charity number 81717 4865 RR0001 CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 I. Bill C-8: An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (conversion therapy) .................................. 2 A. An overly broad definition of “conversion therapy” .............................................................. 2 B. Bill C-8 restricts children’s and adults’ access to care.......................................................... 3 C. Bill C-8 imposes an ideological view of sexuality and gender ............................................... 5 II. Bill C-8 Restricts Health Professionals’ Ability to Treat Children’s Gender Distress without Transition and Medicalization ....................................................................................... 7 A. Bill C-8’s imposition of a single treatment path for children ................................................. 7 B. Violation of practitioners’ and patients’ freedom of thought, opinion, belief and expression 9 C. Political interference with medical and scientific debate limits healthcare options .............. 9 III. Bill C-8’s Violation of the Charter Rights of Children and Parents -

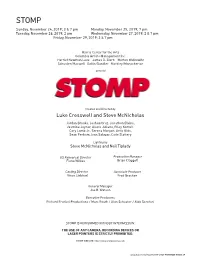

Luke Cresswell and Steve Mcnicholas

STOMP Sunday, November 24, 2019; 3 & 7 pm Monday, November 25, 2019; 7 pm Tuesday, November 26, 2019; 2 pm Wednesday, November 27, 2019; 2 & 7 pm Friday, November 29, 2019; 2 & 7 pm Harris Center for the Arts Columbia Artists Management Inc. Harriet Newman Leve James D. Stern Morton Wolkowitz Schuster/Maxwell Gallin/Sandler Markley/Manocherian present Created and Directed by Luke Cresswell and Steve McNicholas Jordan Brooks, Joshua Cruz, Jonathon Elkins, Jasmine Joyner, Alexis Juliano, Riley Korrell, Cary Lamb Jr., Serena Morgan, Artis Olds, Sean Perham, Ivan Salazar, Cade Slattery Lighting by Steve McNicholas and Neil Tiplady US Rehearsal Director Production Manager Fiona Wilkes Brian Claggett Casting Director Associate Producer Vince Liebhart Fred Bracken General Manager Joe R. Watson Executive Producers Richard Frankel Productions / Marc Routh / Alan Schuster / Aldo Scrofani STOMP IS PERFORMED WITHOUT INTERMISSION. THE USE OF ANY CAMERA, RECORDING DEVICES OR LASER POINTERS IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. STOMP WEBSITE: http://www.stomponline.com www.harriscenter.net 2019-2020 PROGRAM GUIDE 27 STOMP continued STOMP, a unique combination of percussion, movement and to Germany, Holland and France. Another STOMP production visual comedy, was created in Brighton, UK, in the summer of opened in San Francisco in May 2000, running for two and a 1991. It was the result of a ten-year collaboration between its half years. creators, Luke Cresswell and Steve McNicholas. The original cast of STOMP has recorded music for the Tank They first worked together in 1981, as members of the street Girl movie soundtrack and appeared on the Quincy Jones band Pookiesnackenburger and the theatre group Cliff Hanger. -

Ethics, Politics and Feminist Organizing: Writing Feminist Infrapolitics and Affective Solidarity Into Everyday Sexism

Vachhani, S. J., & Pullen, A. (2019). Ethics, politics and feminist organizing: Writing feminist infrapolitics and affective solidarity into everyday sexism. Human Relations, 72(1), 23-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718780988 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1177/0018726718780988 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via SAGE at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0018726718780988 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Ethics, politics and feminist organizing: Writing feminist infrapolitics and affective solidarity into everyday sexism Sheena J. Vachhani University of Bristol, UK Email: [email protected] Alison Pullen Macquarie Universtiy, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper critically examines a twenty-first century online, social movement, The Everyday Sexism Project (referred to as the ESP), to analyse resistance against sexism that is systemic, entrenched and institutionalised in society, including organizations. Our motivating questions are: what new forms of feminist organizing are developing to resist sexism and what are the implications of thinking ethico-politically about feminist resistance which has the goals of social justice, equality and fairness? Reading the ESP leads to a conceptualisation of how infrapolitical feminist resistance emerges at grassroots level and between individuals in the form of affective solidarity, which become necessary in challenging neoliberal threats to women’s opportunity and equality. -

“Sex Work and HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma in Bangladesh”

Sex work and HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Bangladesh Rehana Akhter A Thesis in The Department of Special Individualized Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Special Individualized Program) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2011 © Rehana Akhter, 2011 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Rehana Akhter Entitled: Sex work and HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Bangladesh and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Special Individualized Program) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. David Howes Examiner Dr. Peter Stoett Examiner Dr. Eric Shragge Examiner Dr. Maria Nengeh Mensah Thesis Supervisor Dr. Viviane Namaste Approved by Dr. D. Howes, Graduate Program Director September 2, 2011 Dr. Graham Carr, Dean School of Gradute Studies ii ABSTRACT Sex work and HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Bangladesh Rehana Akhter This paper explores the stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS and sex work and its effect on female sex workers in Bangladesh. In order to identify the roles of two sex worker organizations (Durjoy and Nari Mukti) and to develop the recommendations for them, I conducted my MA thesis in Bangladesh in 2009. In Bangladesh, there is a need for more research on social issues related to HIV/AIDS. Hence, this study’s exploration of both stigma and AIDS issues is valuable. To collect information on these issues, I interviewed eight individual sex workers and conducted six focus group discussions; in total there were 39 participants. -

History of Feminist Bioethics

PHL 870 Seminar in Philosophy of Health Care A History of Feminist Bioethics Hilde Lindemann Wednesdays, 7:00-9:50 516 South Kedzie Hall Office hours: W 3-5 or as you need me [email protected] 353-3981 In Canada and the U.S., the bioethics movement and second-wave feminism both began in the late 1960s, but the two discourses had little to say to one another for the better part of two decades. The few essays by feminists published up to that time in the premier journal in bioethics, the Hastings Center Report, dealt solely with ethical issues surrounding women’s reproductive functions. All that has changed. The 1990s saw a steady stream of conferences, monographs, anthologies, and essays in learned journals that examine bioethical issues through a feminist lens, and now there is a burgeoning literature. In this seminar we will read some of this literature, to get a better idea of what feminist theory has to offer bioethics—and vice-versa. Texts for the course include Susan Sherwin’s No Longer Patient; Susan M. Wolf, ed., Feminism and Bioethics: Beyond Reproduction, Dorothy Roberts’s Killing the Black Body, and Rebecca Kukla’s Mass Hysteria. Seminar participants will do a presentation of one of the readings and lead the discussion for that meeting, for a fourth of their final grade. The seminar paper counts toward the other three-fourths of the grade. Calendar Aug. 29. What is feminist bioethics? Sept. 5. Sherwin, No Longer Patient, Intro., “Understanding Feminism,” “Ethics, ‘Feminine Ethics,’ and Feminist Ethics,” “Feminism and Moral Relativism,” “Toward a Feminist Ethics of Health Care.” Sept. -

Rethinking Feminist Ethics

RETHINKING FEMINIST ETHICS The question of whether there can be distinctively female ethics is one of the most important and controversial debates in current gender studies, philosophy and psychology. Rethinking Feminist Ethics: Care, Trust and Empathy marks a bold intervention in these debates by bridging the ground between women theorists disenchanted with aspects of traditional ‘male’ ethics and traditional theorists who insist upon the need for some ethical principles. Daryl Koehn provides one of the first critical overviews of a wide range of alternative female/ feminist/feminine ethics defended by influential theorists such as Carol Gilligan, Annette Baier, Nel Noddings and Diana Meyers. She shows why these ethics in their current form are not defensible and proposes a radically new alternative. In the first section, Koehn identifies the major tenets of ethics of care, trust and empathy. She provides a lucid, searching analysis of why female ethics emphasize a relational, rather than individualistic, self and why they favor a more empathic, less rule-based, approach to human interactions. At the heart of the debate over alternative ethics is the question of whether female ethics of care, trust and empathy constitute a realistic, practical alternative to the rule- based ethics of Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill and John Rawls. Koehn concludes that they do not. Female ethics are plagued by many of the same problems they impute to ‘male’ ethics, including a failure to respect other individuals. In particular, female ethics favor the perspective of the caregiver, trustor and empathizer over the viewpoint of those who are on the receiving end of care, trust and empathy. -

A Conversation Between Dr. Viviane Namaste and Dalia Tourki

Trans Justice and the Law: From Then to Now, From There to Here: A Conversation between Dr. Viviane Namaste and Dalia Tourki ON THE MARGINS OF LEGAL CHANGE PUBLIC CONFERENCE KEYNOTE* Viviane Namaste and Dalia Tourki The following is an edited transcription of the keynote presentation at the SSHRC- funded conference On the Margins of Trans Legal Change. This public conference was hosted by McGill University’s Faculty of Law and Institute for Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies, in partnership with Thompson Rivers University’s Faculty of Law. The keynote presentation was a conversation between Dr. Viviane Namaste and Dalia Tourki, where they asked each other questions. Keynote Speakers Dr. Viviane Namaste (VN), Professor, Simone de Beauvoir Institute, Concordia University, Montréal. Dalia Tourki (DT), Former Advocate and Public Educator at the Centre for Gender Advocacy, Montreal, and a board member of AGIR (LGBTQ Action with Migrants and Refugees), Montreal. She coordinated research projects, organized marches, published articles, gave numerous conferences, helped introduce a trans rights bill, and spearheaded a lawsuit to advance trans rights in Quebec. Dalia is currently a law student at the Faculty of Law, McGill University. Introduction VN: We are really excited to be here tonight. Originally, two other women were going to be involved in this keynote, but they ultimately weren’t able to participate. * Many thanks to Stephanie Weidmann, Faculty of Law, Thompson Rivers University (2020) for her work on transcribing and revising the keynote into article format, and to Charles Girard for his translation of this article from English to French. Canadian Journal of Law and Society / Revue Canadienne Droit et Société, 2020, Volume 35, no. -

Teacher and Student Resource Pack Lord of the Flies Teacher and Student Resource Pack 1 1

A NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE PRODUCTION TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 1 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK p3 2. WILLIAM GOLDING’S NOVEL p4 William Golding and Lord of the Flies Novel’s Plot Characters Themes and Symbols 3. NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE’S LORD OF THE FLIES p11 An Introduction By Matthew Bourne Production Research Some Initial Ideas Plot Sections Similarities and Differences 4. PRODUCTION ELEMENTS p21 Set and Costume Costume Supervisor Music Lighting 5. PRACTICAL WORKSHEETS p26 General Notes Character Devising and Developing Movement 6. REFLECTING AND REVIEWING p32 Reviewing live performance Reviews and Editorials for New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s Production of Lord of the Flies 7. FURTHER WORK p32 Did You Know? It’s An Adventure Further Reading Essay Questions References Contributors LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 2 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK This pack aims to give teachers and students further understanding of New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s production of Lord of the Flies. It contains information and materials about the production that can be used as a stimulus for written work, discussion and practical activities. There are worksheets containing information and resources that can be used to help build your own lesson plans and schemes of work based on Lord of the Flies. This pack contains subject material for Dance, Drama, English, Design and Music. Discussion and/or Evaluation Ideas Research and/or Further Reading Activities Practical Tasks Written Work The symbols above are to guide you throughout this pack easily and will enable you to use this guide as a quick reference when required. -

Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 4 Issue 4 Spring 2013 Article 5 Spring 2013 Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory Susan Archer Mann University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Mann, Susan A.. 2018. "Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 4 (Spring): 54-73. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol4/iss4/5 This Viewpoint is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory Cover Page Footnote The author wishes to thank Oxford University Press for giving her permission to draw from Chapters 1, 5, 6, 7, and the Conclusion of Doing Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity (2012). This viewpoint is available in Journal of Feminist Scholarship: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol4/iss4/5 Mann: Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage VIEWPOINT Third Wave Feminism’s Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory Susan Archer Mann, University of New Orleans Abstract: This article first traces the history of unhappy marriages of disparate theoretical perspectives in US feminism. In recent decades, US third-wave authors have arranged their own unhappy marriage in that their major publications reflect an attempt to wed poststructuralism with intersectionality theory. -

Feminist Perspectives on Curating

Feminist perspectives on curating Book or Report Section Published Version Richter, D. (2016) Feminist perspectives on curating. In: Richter, D., Krasny, E. and Perry, L. (eds.) Curating in Feminist Thought. On-Curating, Zurich, pp. 64-76. ISBN 9781532873386 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/74722/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.on-curating.org/issue-29.html#.Wm8P9a5l-Uk Publisher: On-Curating All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online ONN CURATING.org Issue 29 / May 2016 Notes on Curating, freely distributed, non-commercial Curating in Feminist Thought WWithith CContributionsontributions bbyy NNanneanne BBuurmanuurman LLauraaura CastagniniCastagnini SSusanneusanne ClausenClausen LLinaina DzuverovicDzuverovic VVictoriaictoria HorneHorne AAmeliamelia JJonesones EElkelke KKrasnyrasny KKirstenirsten LLloydloyd MMichaelaichaela MMeliánelián GGabrielleabrielle MMoseroser HHeikeeike MMunderunder LLaraara PPerryerry HHelenaelena RReckitteckitt MMauraaura RReillyeilly IIrenerene RevellRevell JJennyenny RichardsRichards DDorotheeorothee RichterRichter HHilaryilary RRobinsonobinson SStellatella RRolligollig JJulianeuliane SaupeSaupe SSigridigrid SSchadechade CCatherineatherine SSpencerpencer Szuper Gallery, I will survive, film still, single-channel video, 7:55 min. Contents 02 82 Editorial It’s Time for Action! Elke Krasny, Lara Perry, Dorothee Richter Heike Munder 05 91 Feminist Subjects versus Feminist Effects: Public Service Announcement: The Curating of Feminist Art On the Viewer’s Rolein Curatorial Production (or is it the Feminist Curating of Art?) Lara Perry Amelia Jones 96 22 Curatorial Materialism. -

The Paradox of Authenticity: the Depoliticization of Trans Identity

The Paradox of Authenticity: The Depoliticization of Trans Identity THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Meredith Cecilia Lee Graduate Program in Women's Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Professor Shannon Winnubst, Advisor Professor Mary Thomas Professor Jian Chen Copyright by Meredith Cecilia Lee 2012 Abstract The language of authenticity that valorizes the mind over the body is embedded in Cartesian dualism, which thereby inspires an entirely personal understanding of self- fulfillment. Within the trans community, this language depoliticizes trans issues by framing nonnormative gender presentation as a personal issue. This paper examines the relationship of Cartesian dualism to the paradoxes of authenticity in trans medico- scientific discourse. For example, to express authenticity and gain social recognition within the medical model of trans identity, an individual must articulate her/his desire within the normative language of the medical establishment; therefore, the quest for authenticity is already foreclosed through the structures of normalization. This paper argues that, while medical procedures typically normalize one’s body to “pass” as the other sex, these procedures are also necessary for many trans individuals to gain social recognition and live a bearable life. The notion that trans individuals are “trapped” in the wrong body has been the dominant paradigm since at least the 1950s. This paper argues that centering gender in the body constructs gender as ahistorical and thereby erases the political, economic, and cultural significance of trans oppression and struggle. This paper concludes that the systematic pathologization of nonnormative sex/gender identification has historically constituted the notion that gender trouble is indeed a personal problem that should be cured through medical science. -

Mainstream Feminism

Feminist movements and ideologies This collection of feminist buttons from a women's museum shows some messages from feminist movements. A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought. Groupings Judith Lorber distinguishes between three broad kinds of feminist discourses: gender reform feminisms, gender resistant feminisms, and gender revolution feminisms. In her typology, gender reform feminisms are rooted in the political philosophy of liberalism with its emphasis on individual rights. Gender resistant feminisms focus on specific behaviors and group dynamics through which women are kept in a subordinate position, even in subcultures which claim to support gender equality. Gender revolution feminisms seek to disrupt the social order through deconstructing its concepts and categories and analyzing the cultural reproduction of inequalities.[1] Movements and ideologies Mainstream feminism … "Mainstream feminism" as a general term identifies feminist ideologies and movements which do not fall into either the socialist or radical feminist camps. The mainstream feminist movement traditionally focused on political and legal reform, and has its roots in first- wave feminism and in the historical liberal feminism of the 19th and early- 20th centuries. In 2017, Angela Davis referred to mainstream feminism as "bourgeois feminism".[2] The term is today often used by essayists[3] and cultural analysts[4] in reference to a movement made palatable to a general audience by celebrity supporters like Taylor Swift.[5] Mainstream feminism is often derisively referred to as "white feminism,"[6] a term implying that mainstream feminists don't fight for intersectionality with race, class, and sexuality.