Agricultural Management Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beatty Cramer House (CR # 21-02)

DocuSign Envelope ID: 2DB235E3-0717-4035-B0B5-3FF91AF7EE2A Frederick County, Maryland Staff Report Concurrence Form To: Office of the County Executive Date: 05/07/2021____________________ Division Director: Steve__________________ Horn __ Approved: __________________________ From: Kimberly________________ Golden Brandt _____________ Division: Planning_________________ & Permitting __________ Phone #: 301-600-1144____________________ Staff Report Topic: : Proposed Listing on County Register of Historic Places – Beatty Cramer House (CR # 21-02) Time Sensitive? Yes □ (if yes, deadline for approval: ____________________) No □X Action Requested by Executive’s Office: Signature Requested □X OR Information Only □ Staff Report Review: This staff report has been thoroughly reviewed first by the appropriate divisions/agencies noted on Page 2 followed by those outlined below: Name Signature Date Budget Office Kelly Weaver 5/10/2021 Finance Division Erin White 5/10/2021 County Attorney’s Office Kathy L Mitchell 5/10/2021 Refer to County Council? Yes □X No □ (County Attorney’s Office to complete) Chief Administrative Rick Harcum 5/13/2021 Officer County Executive Jan Gardner 5/13/2021 Forward to Council? Yes □X No □ (County Executive to complete) Page 1 of 2 May 2020 DocuSign Envelope ID: 2DB235E3-0717-4035-B0B5-3FF91AF7EE2A Frederick County, Maryland Staff Report Concurrence Form Other Reviewers: Title Name Signature Date 3. Director, Livable Frederick Kimberly Golden Brandt 5/7/2021 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Comments: From Date Comment Page 2 of 2 May 2020 -

A Finishes Study of the Dutch-American Stone Houses of Bergen County, New Jersey

THE COLORS OF CULTURE: A FINISHES STUDY OF THE DUTCH-AMERICAN STONE HOUSES OF BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Kimberly Michele De Muro Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Historic Preservation Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Columbia University May 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ iii Introduction .................................................................................................................................... iv Methodology .................................................................................................................................. ix Chapter 1: The Early History of Colonial Bergen County and the Bergen County Dutch ............. 1 Chapter 2: The Perseverance of Dutch Culture in Northern New Jersey ....................................... 7 Chapter 3: The Evolution of Dutch-American Architecture ......................................................... 11 Chapter 4: The Availability of Pigments to the Residents of Bergen County and the Consumer Revolution of the Eighteenth Century .......................................................................................... 19 Transportation and Trade in Colonial New Jersey .................................................................... 19 Painters’ Colors and Pigments in New York City and the American Colonies ........................ 22 Chapter -

Volume 27 , Number 2

THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Mark James Morreale, Guest Editor Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College. COL Lance Betros, Professor and Head, Department of History, U.S. Military James M. Johnson, Executive Director Academy at West Point Research Assistants Kim Bridgford, Professor of English, Gabrielle Albino West Chester University Poetry Center Gail Goldsmith and Conference Amy Jacaruso Michael Groth, Professor of History, Wells College Brian Rees Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, State University of New York at New Paltz Hudson River Valley Institute Advisory Board Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- Peter Bienstock, Chair Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Margaret R. Brinckerhoff Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Dr. Frank Bumpus Fordham University Frank J. Doherty H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey Vassar College Shirley M. Handel Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Marjorie Hart Marist College Maureen Kangas Barnabas McHenry David Schuyler, -

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Transportation Analysis Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Van Buren National Historic Site New York Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Transportation Analysis Report PMIS No. 73134 October 2010 Martin Van Buren National Historic Site – Existing Transportation Conditions Report – January 2010 1 Table of Contents Section 1: Existing transportation conditions ......................................................................................................... 3 Section 2: Area trail connections ............................................................................................................................ 31 Section 3: Signage ...................................................................................................................................................... 43 Section 4: Roadway Considerations ....................................................................................................................... 58 Section 5: Parking ..................................................................................................................................................... 66 Section 6: School and Charter Bus Service ............................................................................................................ 73 Document Review ................................................................................................................................................... 79 Martin Van Buren National Historic Site – Existing Transportation Conditions Report – January 2010 2 -

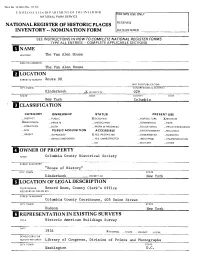

(Owner of Property

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) U Nil hl)SI AILS Dl PARTMhNI Ol THL IML.klOR FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC The Van Alen House AND/OR COMMON The Van Alen House [LOCATION STREETS NUMBFR ROUte 9H _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Kinderhook _2L VICINITY OF 029 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York Columbia HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE _ DISTRICT —.PUBLIC 2LOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE --SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ...ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT __IN PROCESS 2LYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC -..BEING CONSIDERED — YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Columbia County Historical Society STREETS NUMBER ^House of History" CITY, TOWN STATE Kinderhook VICINITY OF New York [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Record Room, County Clerk's Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC STREET & NUMBER Columbia County Courthouse, 405 Union Street CITY, TOWN STATE Hudson New York [| REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1934 X FEDERAL _...STATE —COUNTY ..LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE J^GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Adam Van Alen House, near Kinderhook, New York, is a one-and-a-half storey brick farmhouse built in two distinct parts. -

Elevated Soul Food & Live Music Venue

HUDSON VALLEY REGION eat COUNTY www.thegreensatcopake.com play www.copakecountryclub.com stay www.thebarnatcopakelake.com ELEVATED SOUL FOOD & LIVE MUSIC VENUE helsinkihudson.com 405 Columbia St Hudson NY 518.828.4800 COLUMBIACOUNTYTOURISM.ORG BETTER TOGETHER You and your TKG agent, Making vacation home dreams come true Hudson Chatham Stockbridge Pittsfi eld 413-329-1162 [email protected] TKGRE.COM Serving the Hudson Valley and the Berkshires To Vermont DRIVING TIMES Albany, NY 35 min Hartford, CT 1 1/2 hrs RENSSELAERBIA CO. CO. Poughkeepsie, NY 45 min Boston, MA 2 1/2 hrs COLUM To Albany 9 22 New York City, NY 2 hrs Montreal, CAN 4 1/2 hrs 5A 20 Lebanon Valley New To Albany 66 Raceway Lebanon Malden 9 BERKSHIRE CO. Knickerbocker Hand Hollow Lake Bridge 32 Conservation 20 32 North Albany Turnpike 13 Area To Albany Chatham 34 Theater Barn . d Shaker RENSSELAER CO. 9 28B R BIA CO. m Village COLUM u NEW LEBANON 22 e 17 s To u Mt. 5 Pittsfield 28 M Old Chatham r 9 Lebanon Kinderhook e k 66 a Lake h 21 S Niverville O. 90 KINDERHOOK 13 Shaker Queechy 203 Museum 295 Lake 9 & Library East Chatham HUDSON RIVER HUDSON 30 9J Valatie Canaan COLUMBIA C 9H Chatham CHATHAM CANAAN BERKSHIRE CO. Center Ooms Conservation 90 To STUYVESANT Area at Richmond 66 Sutherland and Lenox Kinderhook 203 Pond Schor S Conservation Stuyvesant Vanderpoel Martin 295 Area House Van Buren 21 Park Chatham Borden’s Pond 5 26A Van Alen Conservation 90 Area NEW YORK House 21B 24 MASSACHUSETT Stuyvesant 25A “Lindenwald” 9 Falls Martin Van Buren Mac-Haydn To Springfield 46 25 National Historical Theatre Beebe Hill and Boston Site State Forest JOLSEN 21 Fairgrounds 5 BLVD. -

For Nearly Three Hundred Years, the Home of Jan Van Hoesen Has Stood Overlooking the Claverack Creek, About Two Miles from the Hudson River’S Eastern Shore

Jan van Hoesen House, Claverack, NY by Thomas E. Rinaldi & Rob Yasinsac From Hudson Valley Ruins: Forgotten Landmarks of an American Landscape, Published by UPNE, 2006 Reproduced Here With Permission Of Publisher. Copyrighted Material. For nearly three hundred years, the home of Jan van Hoesen has stood overlooking the Claverack Creek, about two miles from the Hudson River’s eastern shore. Today the house is empty. Though historians recognize this as being one of the oldest and most important examples of residential architecture in the Hudson Valley, decades of neglect have left the house a desolate ruin. Once it was common to find the Hudson’s old Dutch houses in varying states of disrepair. In recent years many homes from this period have been carefully restored or even made into museums, but this old mansion remains a landmark forgotten by most. The original main facade of the Jan van Hoesen house has been altered, but its symmetrical arrangement can still be discerned Though small by today’s standards, the Van Hoesen house was one of the grandest on the Hudson when built, around the year 1720. It stands on a tract of land purchased by Jan Franse van Hoesen, the grandfather of its builder, who came to New Netherland via Amsterdam from Husum, near Hamburg on Germany’s North Sea cost. A seafarer by trade, Van Hoesen arrived at New Amsterdam in 1639 and eventually made his way up the river to Beverwyck (now Albany), where he settled with his family. In 1662 he negotiated the purchase of a large tract of land south of Beverwyck from the native Mahicans, at the site of the future city of Hudson. -

Walking Tour Brochure

Village of Kinderhook Farther Afield HISTORIC The settlement at Kinderhook (Dutch, “children’s 29 Luykas Van Alen House: 2589 Route 9H (1737) corner”) began in the 1660s by Dutch families One of the finest examples of Dutch architecture, this from Albany. Originally called het Dorp or Groot house features parapet gables, Dutch doors and stoops, distinctive Dutch brickwork, and iron beam anchors. The Stuk, the settlement formed on the west bank of KINDERHOOK home was designated a National Historic Landmark in the Kinderhook Creek on lands purchased from 1967 and is open for tours during the summer. the Mahican Indians. 30 Ichabod Crane Schoolhouse: (ca. 1850) VILLAGE During colonial times, large farms and spacious lots Now on the grounds of the Van Alen House. This one- shaped the nascent hamlet. Roads in place then – first room schoolhouse was moved kitty-corner from the A Walking & Bicycling Tour William Street and later Hudson, Albany, and Broad other side of Route 9H in 1974 by the Columbia County Streets – formed a pattern that remains to this day. Historical Society. The building was a functioning school until 1940. The name Ichabod Crane comes from the Washington Irving tale, The Legend of Sleepy Colorful historic figures passed through Kinderhook Hollow. Jesse Merwin, a local schoolteacher, was the during the American Revolution. One of them was prototype for the main character. Colonel Henry Knox, whose horse-drawn sledges carried artillery through the village in January 1776 31 Lindenwald – Martin Van Buren National Historic en route from Ticonderoga to Boston. Site: 1013 Old Post Road (1797) Built by Peter Van Ness in Following the Revolution, Kinderhook experienced 1797, this house was later purchased by President significant growth as it emerged as a postal and Martin Van Buren as his stagecoach stop between Albany and New York retirement home. -

Dutch Farming Heritage Trail

KINDERHOOK COMMUNITY TRAILS KINDERHOOK. NEW YORK Dutch Farming Heritage Trail COMMUNITY TRAILS Community members in the towns of Kinderhook, Stuyvesant and Stockport have been busy over the last decade investigating the possibility of establishing recreational trails within their towns. Together they have explored the idea of also creating a longer inter- mu nicipal trail linking the three communities. The pace and scope of trail planning quickened in 2010 thanks to a grant from the Hudson River Valley Greenway. That work has inspired the development and completion of the Dutch Farming Heritage Trail. It’s hoped that this trail will serve as a catalyst and a model for a web of multiple use trails linking the three towns. Please use the trail regularly and enjoy it respo nsibly. Always respect the rights of property owners and abutters. TRAIL ROUTE The trail runs from the back of the Van Alen House property, owned by Columbia County Historical Society, through areas of Roxbury Farm, down a historic portion of Old Post Road, and to the parking lot of the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site. Hikers can enjoy forest, farm, and stream views, while hiking along rolling hills. Not only does the trail connect the two National Historic Landmarks, but it also provides the opportunity to tie together the evolution of Dutch farming across four centuries. The story begins in the 1700’s, with the Van Alen family farming the land. Gone are the farm structures that likely dotted the landscape, which might well have included a Dutch barn and hay barracks. Where there is now early successional forest, there once were fields of crops, including hay and flax. -

Newsletter Vol.14, No.10-12

The Society for the Preservation of Hudson Valley Vernacular Architecture October – December 2011 Newsletter Vol.14, No.10-12 The Society for the Preservation of many of you fully know, HVVA membership Hudson Valley has many fine restoration craftsmen within Vernacular Architecture its ranks, so here is your chance guys to is a not-for-profit corporation formed reach out to the multitudes and contribute to study and preserve vernacular some tips for keeping our history standing architecture and material culture. proud for future generations. Peter Sinclair – Founder, Trustee Emeritus Understanding that each is endowed West Hurley, Ulster County, NY with differing talents to use for the better- Walter Wheeler – President ment of our community, if you can repair Troy, Rensselaer County, NY walls or make window sashes, but don't (518) 270-9430 claim a talent to write an article about it, [email protected] we have a couple of folks who are willing – Vice President to do the writing for you. So craftsmen, lets Gardiner,Ken Walton Ulster County, NY Drawings by Peter Sinclair get banging away building a response to (845) 883-0132 your fellow members request! Thanks to all [email protected] From the Editor: of you who have returned the survey; those Karen Markisenis – Secretary Congratulations to you all! You all who haven't can find a survey form to print Lake Katrine, Ulster County, NY played an important role in historic preser- out at www.HVVA.org. It is never to late to (845) 382-1788 vation during 2011! The HVVA community tell us what you want, but we need to hear [email protected] is stronger than ever. -

Architectural Traditions in the Hudson River Valley Hudsonrivervalley.Com

106884d_A_Architecture.qxp 8/3/16 7:42 AM Page 1 Map & Guide Series Hudson River Valley Architectural Traditions National Heritage Area, New York hudsonrivervalley.com in the Hudson River Valley he Hudson River Valley is known not only for its natural beauty but its architectural heritage. It was here that architects developed early residential Tstyles, created mountain resorts, and designed spectacular riverside estates. America’s first travel guides touted these architectural wonders 150 years ago. The invitation still holds: Visit the farmhouses of Dutch and French Huguenot settlers; tour the mansions and grounds along the river; and marvel at the creations of some of the country’s greatest 19th-century architects. Staatsburgh State Historic Site, photi by Andrew Halpern Dutch, Huguenot Influences neighbors. Huguenot Street, arguably the Origins of the Great Estates Clermont established a new standard for The houses built by Dutch colonists oldest street in America with its original As second- and third-generation the country house and the prominence during the 17th and early 18th centuries houses, includes three with portions that colonists became more prosperous, of the Livingston family. Federal-era are the only examples of Dutch architec- date back to the 1690s: the Bevier-Elting, many early landholdings expanded. mansions, such as Ten Broeck Mansion ture in North America. Farmhouses, such Jean Hasbrouck, and Abraham Hasbrouck Frederick Philipse I, a Dutch carpenter (1789) in Albany, Boscobel (1804-07) in as Pieter Bronck’s brick residence (1663) houses. The buildings are of local stone, who emigrated in the 1650s, successfully Cold Spring, and Locust Lawn (1814) in in Coxsackie, feature distinctive pitched with steeply pitched shingled roofs and acquired a large amount of land and two New Paltz, demonstrated the increasing roofs with gable ends, prominent roof Dutch jambless fireplaces. -

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site New York

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Van Buren National Historic Site New York Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Alternative Transportation Feasibility Study PMIS No. 73134 May 2012 Table of Contents Report Notes ........................................................................................................ i Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. i Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Project overview ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Existing Conditions ............................................................................................. 2 Park location ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Nearby attractions .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Hudson River Valley Greenway ......................................................................................................................... 7 Visitation ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 Bus/shuttle service ...........................................................................................................................................