Study on Competition Between Airports and the Application of State Aid Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

AOA-Summer-2015.Pdf

THE AIRPORT OPERATORTHE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE AIRPORT OPERATORS ASSOCIATION DELIVERING A BETTER AIRPORT London Luton Features DELIVERING A A LEAP OF FAITH BETTER LUTON Charlotte Osborn, Chaplain, Chief Executive, Nick Barton Newcastle International SECURITY STANDARDS SMALLER AIRPORTS THE WAY AHEAD The House of Commons Transport Peter Drissell, Director of Select Committee reports SUMMER 2015 Aviation Security, CAA ED ANDERSON Introduction to the Airport Operator THE AIRPORT the proposal that APD be devolved in MARTIJN KOUDIJS PETE COLLINS PETE BARNFIELD MARK GILBERT Scotland. The Scottish Government AIRPORT NEEDS ENGINEERING SYSTEM DESIGN BAGGAGE IT OPERATOR THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE AIRPORT OPERATORS ASSOCIATION has made it clear that it will seek GARY MCWILLIAM ALEC GILBERT COLIN MARNANE SERVICE DELIVERY CUSTOMER SOLUTIONS INSTALLATION to halve the APD rate in Scotland. AIRPORT OPERATORS ASSOCIATION Whilst we welcome reductions in the current eye watering levels of APD, Ed Anderson we absolutely insist on a reduction Chairman anywhere in the UK being matched by Darren Caplan the same reduction everywhere else. Chief Executive We will also be campaigning for the Tim Alderslade Government to incentivise the take up Public Affairs & PR Director of sustainable aviation fuels, which is Roger Koukkoullis an I welcome readers to this, an initiative being promoted by the Operations, Safety & Events Director the second of the new look Sustainable Aviation coalition. This Airport Operator magazine. I has the potential to contribute £480 Peter O’Broin C hope you approve of the new format. million to the UK economy by 2030. Policy Manager Sally Grimes Since the last edition we have of We will also be urging real reductions Events & Member Relations Executive course had a General Election. -

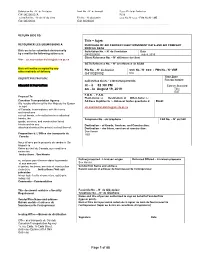

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

The Leading Search Engine Solution Used by 7 French Airports Liligo.Com Has Just Signed a Partnership with Strasbourg Airport

Press Release Paris, 31/03/2014 liligo.com: the leading search engine solution used by 7 French airports liligo.com has just signed a partnership with Strasbourg airport. To date, 7 main French airports have chosen liligo solution, making liligo.com the leading provider to power their websites with its innovative state of the art flights, hotels and car hire white label search engine product. liligo.com search engine white-label solution is comprehensive and unbiased. These core values are essential to airports websites as is also the ability to withstand very important search volumes. For these reasons, several French airports, representing 22.3% of passengers’ traffic in France, chose liligo.com’s “tailor-made” approach. Marseille Provence Airport, France’s 3rd largest regional airport for passenger traffic* with more than 8 million passengers and 108 direct destinations, has been using liligo.com’s white-label solution since 2008. The airport is Routes Europe 2014 host and liligo.com is sponsoring the event. Toulouse - Blagnac Airport, France’s 4th largest regional airport, with 7.5 million passengers in 2013*, hundreds of direct destinations and growing traffic, has also chosen liligo.com's white-label solution. Toulouse - Blagnac Airport is connected to all of Europe's major hubs. “Toulouse-Blagnac Airport has chosen liligo.com to help our passengers find the best travel solutions from Toulouse, whether they are looking for flights, holidays or hotels,” comments Jean- Michel Vernhes, Head of the Airport's Board of Directors. “With liligo.com, our passengers can compare the best travel offers and filter their searches by timetables, departure times, airlines, etc. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

Economics of Airport Operations(Pp

Accepted manuscript. Not for distribution. Please quote as: Beria, P., Laurino, A., & Nadia Postorino, M. (2017). Low-Cost Carriers and Airports: A Complex Relationship. In The Economics of Airport Operations(pp. 361-386). Emerald Publishing Limited. Book series: Advances in Airline Economics Volume 6: “Economics of airport operations” CHAPTER 14 Low-cost carriers and airports: A complex relationship Paolo Beria*, Antonio Laurino and Maria Nadia Postorino *author contact information: [email protected] Abstract In the last decades, low-cost carriers have generated several changes in the air market for both passengers and airports. Mainly for regional airports, low-cost carriers have represented an important opportunity to improve their connectivity levels and passenger traffic. Furthermore, many regional airports have become key factors to regenerate the local economy by improving accessibility and stimulating several markets, such as tourism. However, the relationship between low-cost carriers and airports is rather complex and the outcomes not always predictable. In order to analyse and understand better such relationship and its outcomes, this chapter discusses the main underlying factors identified in: relation with the regional air market (secondary/primary airports), balance of power (dominated/non-dominated airports) and industrial organisation (bases/non-bases). Starting from the proposed Relative Closeness Index, which combines yearly airport passengers and distance between airport pairs, a large sample of European airports is analysed. Then, a smaller sub-sample – which includes selected, significant case studies referring to mid-sized airports – is discussed in detail. Among the main findings, airports sharing their catchment area with others are in a very risky position, due to the potential mobility of LCCs, while geographically isolated airports in good catchment areas can better counterbalance the power of carriers. -

NORWICHBOURNEMOUTH 2021/22 Destinationschedule Guide Issue 2

from NORWICHBOURNEMOUTH 2021/22 DestinationSchedule guide Issue 2 Destination Days of Operation Current schedule Airline Destination Days of Operation Current schedule Airline (from 29 March 2021) (from 29 March 2021) BARBADOS NORWAY Caribbean Fly/Cruise M T W T F S S 04 & 25 Feb 2022 Fjords Fly/Cruise (Bergen) M T W T F S S 26 Feb 2022 CYPRUS POLAND ‡ * ‡ * Paphos M T W T F S S 19 May – 03 Nov 2021 Krakow M T W T F S S Year round from 01 May 2021 04 May – 19 Oct 2022 M T W T F S S 01 June – 30 Oct 2021 PORTUGAL ° ◊ ° ‡ ** Faro M T W T F S S Year round from 03 May 2021 FRANCE Bergerac NEW M T W T F S S 02 June – 27 Oct 2021 SPAIN * ‡ ** ‡ * ‡ ** Alicante M T W T F S S Year round from 03 May 2021 GREEK ISLANDS Girona (Barcelona) M T W **T F S **S 03 May – 30 Oct 2021 Corfu M T W T F S S 17 May – 22 Oct 2021 Gran Canaria M T W T F S S 04 Oct – 25 Apr 2022 02 May – 24 Oct 2022 03 – 31 Oct 2022 Crete (Heraklion) M T W T F S S 06 May – 21 Oct 2022 Ibiza M T W T F S S 05 May – 20 Oct 2022 ^* Kefalonia M T W T F S S 18 May – 14 Sep 2021 Lanzarote M T W T F S S Year round from 20 May 2021 03 May – 13 Sep 2022 * ‡ † ** * ◊ Malaga M T W T F S S Year round from 01 May 2021 M T W T F S 22 May – 23 Oct 2021 * † ** * Rhodes S Majorca M T W T F S S ** 01 May – 30 Oct 2021 07 May – 29 Oct 2022 * ^^ M T * W T F S S * 18 May – 24 Oct 2021 Zante M T W T F S S 23 May – 19 Sep 2021 02 Apr – 23 Oct 2022 01 May – 18 Sep 2022 Menorca M T W T F S S 19 May – 20 Oct 2021 04 May – 19 Oct 2022 ITALY Murcia M T W T F S S 04 Jun – 29 Oct 2021 ‡ ‡ Bergamo (Italian Lakes) -

AOA URGES BUDGET SUPPORT for UK AVIATION and Warns That the Survival of UK Airports Is at Stake

THE AIRPORT OPERATORTHE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE AIRPORT OPERATORS ASSOCIATION AOA URGES BUDGET SUPPORT FOR UK AVIATION and warns that the survival of UK airports is at stake Features LEEDS BRADFORD SOUTHAMPTON AIRPORT Plans for a new £150m terminal tells local council ts future approved in principle depends on a runway extension EIGHT ENGLISH AIRPORTS HOPES RISE FOR SPRING 2021 bid for freeport status Stansted expansion 2 THE AOA IS PLEASED TO WORK WITH ITS CORPORATE PARTNERS, GOLD AND SILVER MEMBERS Corporate Partners Gold Members Silver Members WWW.AOA.ORG.UK 3 KAREN DEE Introduction to The Airport Operator THE AIRPORT All of these moves amount to a Welcome to heartening vote of confidence OPERATOR from the owners of airports that THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE AIRPORT OPERATORS ASSOCIATION this edition of we will recover and be a vibrant, successful sector again. But, while AIRPORT OPERATORS ASSOCIATION The Airport that is really good news for the future, it shouldn’t distract us from The Baroness Ruby Operator the desperate situation that many McGregor-Smith CBE airports find themselves in now after Chair which tells the Government has, in effect, forced Karen Dee the story of them to close down their passenger Chief Executive operations. Henk van Klaveren how UK airports are fighting Head of Public Affairs & PR The Office of National Statistics to survive the worst crisis recently confirmed that air travel has Christopher Snelling that they have ever seen, but suffered more from the pandemic Policy Director than any other sector. The UK Rupinder Pamme also points to some optimism Government’s statement that Policy Manager international travel restrictions will Patricia Page about the future. -

Market Segmentation in Air Transportation in Slovak Republic

Volume XXI, 40 – No.1, 2019, DOI: 10.35116/aa.2019.0006 MARKET SEGMENTATION IN AIR TRANSPORTATION IN SLOVAK REPUBLIC Marek PILAT*, Stanislav SZABO, Sebastian MAKO, Miroslava FERENCOVA Technical university of Kosice, Faculty of aeronautics *Corresponding author. [email protected] Abstract. This article talks about segmentation of air transport market in the Slovak Republic. The main goal was to explore all regular flights from three International airports in Slovak Republic. The researched airports include M.R. Štefánik in Bratislava, Košice International Airport and Poprad - Tatry Airport. The reason for the selection of airports was focused on scheduled flights. The main output of the work is a graphical representation of scheduled flights operated from the territory of the Slovak Republic. The work includes an overview of airlines, destinations, attractions, and other useful information that has come up with this work. Keywords: Airport; segmentation; scheduled flights 1. INTRODUCTION The main aim of this article is to point out the coverage of the air transport market from the territory of the Slovak Republic. Initial information was processed for three International airports and their regular flights to different parts of the world. We chose M.R. Stefanik in Bratislava, Kosice International Airport and Poprad - Tatry Airport. In practical part the authors collected all regular flights from the airports and processed them in table form. All these lines were needed to develop a comprehensive graphical model which is also the main output. The graphical model clearly shows where it can be reached from the territory of the Slovak Republic by a direct route. All data is current for the 2018/2019 Winter Timetable with all the current changes, whether in terms of line cancellation or adding new carriers to new destinations. -

Gibraltar Airport Operators Association

ISSUE SPONSORED BY ISSUE SPONSORED BY The official magazine of the GIBRALTAR Airport Operators Association AIRPORT: NEW SPRING 2013 TERMINAL TRANSFORMING AIR TRAVEL Policy Features News AOA launches ‘Airport Operators TV’ Bristol Airport’s dynamic development Newcastle Airport launches new website ‘A Fair Tax on Flying’ St Helena’s £201.5m Airport Project RPS: logistical masterplanning at Manchester New night noise regime moves closer LHR Runway Resilience Project Birmingham appoints new aviation strategy specialist Delivering world class integrated baggage handling solutions Babcock provides integrated solutions which support We are one of the UK’s leading organisations providing critical airport operations, helping to keep passengers through-life integrated solutions and support services for moving and fl ights on schedule. Our services airport baggage handling. With over 15 years experience, encompass designing, installing and managing Babcock uses its unrivalled baggage processing and complex baggage handling systems, through to fl eet operational knowledge, together with its specialist management and engineering support for specialist engineering skills in automated handling and control ground support vehicles. systems development, to deliver the optimum throughlife performance in terms of cost, effi ciency and reliability. www.babcock.co.uk babcock-spring2013-1.0.indd 1 27/02/2013 09:54 p.3 WWW.AOA.ORG.UK THE Airport Operator SPRING 2013 Ed Anderson, Chairman, Airport Operators Association The official magazine of the Airport Operators Association CHAIRMAN’S IntRODUctION Airport Operators’ Association 3 Birdcage Walk Welcome to this edition of to ensure that all aspects of London the Airport Operator which the passenger experience are SW1H 9JJ is published on the occasion of excellent and we therefore Tel: 020 7799 3171 Fax: 020 7340 0999 our Annual Dinner at the welcome the appointment of Grosvenor House Hotel. -

Global Volatility Steadies the Climb

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Global volatility steadies the climb Cirium Fleet Forecast’s latest outlook sees heady growth settling down to trend levels, with economic slowdown, rising oil prices and production rate challenges as factors Narrowbodies including A321neo will dominate deliveries over 2019-2038 Airbus DAN THISDELL & CHRIS SEYMOUR LONDON commercial jets and turboprops across most spiking above $100/barrel in mid-2014, the sectors has come down from a run of heady Brent Crude benchmark declined rapidly to a nybody who has been watching growth years, slowdown in this context should January 2016 low in the mid-$30s; the subse- the news for the past year cannot be read as a return to longer-term averages. In quent upturn peaked in the $80s a year ago. have missed some recurring head- other words, in commercial aviation, slow- Following a long dip during the second half Alines. In no particular order: US- down is still a long way from downturn. of 2018, oil has this year recovered to the China trade war, potential US-Iran hot war, And, Cirium observes, “a slowdown in high-$60s prevailing in July. US-Mexico trade tension, US-Europe trade growth rates should not be a surprise”. Eco- tension, interest rates rising, Chinese growth nomic indicators are showing “consistent de- RECESSION WORRIES stumbling, Europe facing populist backlash, cline” in all major regions, and the World What comes next is anybody’s guess, but it is longest economic recovery in history, US- Trade Organization’s global trade outlook is at worth noting that the sharp drop in prices that Canada commerce friction, bond and equity its weakest since 2010. -

Bratislava and Košice Competition Between Regions

Herbert Kaufmann Member and Speaker of the Management Board Flughafen Wien AG Vienna International Airport A strong partner for Bratislava and Košice Competition between Regions The competitors of the Bratislava-Vienna region include Munich, Milan, Paris, Prague, etc. The Bratislava-Vienna region must define itself as a common region and develop its unique site factors. Vienna & Bratislava Airports Wide-ranging opportunities for growth 2005: 17.0 million passengers 2015: 30.0 million passengers Thereof 6 – 7 million in Bratislava For each one million passengers: 1000 new jobs at the airport Cooperation allows for the best development of potential • Vienna: primarily transfer hub west/east/long-haul • Bratislava: primarily point-to-point traffic Business, charter, low-cost carriers Competitive advantages over airports like Zurich, Munich, Prague etc. For Bratislava, more growth than with any other solution. Commitment to linking Bratislava Airport with the Vienna market • Express connections between Vienna City Centre – BTS Airport less than 1 hour travelling time • CAT operator (majority ownership Flughafen Wien AG) • Product meets highest demands by passengers e.g. city check-in with baggage Commitment to linking Bratislava Airport with the Vienna market • Construction of rail connections by 2009 (project by ÖBB and Flughafen Wien AG guaranteed by cooperation agreement) • Starting in mid-2006: Opening of city check-in in Vienna for flights from Bratislava plus bus connections Connections between Bratislava Airport and Vienna Gänsernd. Floridsdorf Marchegg Devínska Stadlau Nova Ves Bratislava Kl. St. Wien Mitte Bratislava Petržalka Flughafen Wolfsthal Wien Wien ZVBf. Wien Süd Hegyes- halom Vision for Bratislava More – Destinations – Frequencies – Passengers than with any other solution According to the Interreg III-A study by the EU, cooperation could create up to 35,000 new jobs in the region.