An Early Nineteenth Century Malting Business in East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felixstowe Northern Fringe Landscape and Visual Appraisal of Land to the North of the A14(T) to Assess Suitability for Housing Growth For

Felixstowe Northern Fringe Landscape and visual appraisal of land to the north of the A14(T) to assess suitability for housing growth for Suffolk Coastal District Council July 2008 Quality control Landscape and visual appraisal of land to the north of the A14(T) Felixstowe Northern Fringe Checked by Project Manager: Approved by: Signature: Signature: Name: Louise Jones Name: Simon Neesam Title: Associate Title: Associate Director Date: Date: The Landscape Partnership is registered with the Landscape Institute, the Royal Town Planning Institute, and is a member of the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment The Landscape Partnership Registered office Greenwood House 15a St Cuthberts Street Bedford MK40 3JB Registered in England No. 270900 Status: Issue Felixstowe Northern Fringe Landscape and Visual Appraisal 1 Introduction 1.1 The Landscape Partnership was appointed by Suffolk Coastal District Council in May 2008 to undertake a landscape and visual appraisal of areas of land to the north of Felixstowe [north of A14(T)] to assess suitability for housing growth. Qualifications and Experience 1.2 The Landscape Partnership is a practice of Landscape Architects, Urban Designers, Environmental Planners, Arboriculturists and Ecologists established in 1986. The practice has considerable experience in environmental impact assessment and landscape design for a wide variety of projects types and scales including the assessment of buildings in the countryside. It is currently delivering these services to Suffolk County Council under a strategic partnership arrangement and has dealt with a number of major infrastructure projects in the eastern region. 1.3 The practice also has considerable experience in the process of landscape characterisation and assessment. -

Peyton Hall Cottage Ramsholt | Woodbridge | Suffolk | IP12 3AA Guide Price £375,000 Freehold

Peyton Hall Cottage Ramsholt | Woodbridge | Suffolk | IP12 3AA Guide Price £375,000 Freehold Peyton Hall Cottage is an that may offer further potential as a snaps or to provide welcoming second exit for the B1083. Continue on enchanting one bedroom ground floor double bedroom or background heat in readiness for your this road past Shottisham and on second reception room (subject to the arrival if the property is to be used as a towards Alderton. On a sharp left hand character home enjoying a rural necessary consents). holiday home or rural retreat. The bend, there will be a road to the right, position. The cottage is water is heated by an immersion heater. signposted Ramsholt 2. After 2 miles surrounded by fields within the The cottage offers a blend of exposed The well is situated beneath the patio there is a sharp right hand bend, and highly regarded village of brick floors and wooden floor boards, a and we are advised that it has been then take a dirt track on the left shortly Ramsholt on the northern shore feature fireplace with inset wood burner overhauled by making it deeper (via a after bend. Little white cottage under within the sitting/dining room, a solid bore hole) and by updating the electrics trees. The garden goes back to the of the River Deben. fuel range style cooker in the kitchen and pump. bend. that heats four radiators within the About the Property property and there is space for a wood About the Area Services Ramsholt is located near Woodbridge burner in the study. -

Ipswich Geological Group

IPSWICH GEOLOGICAL GROUP BULLETIN No. 1 August 1966 Contents Author Title Original Pages H. E. P. Spencer, F.G.S. Geographic and Geological Notes on the 1-3 Ipswich District R. A. D. Markham Coast Erosion 4 S. J. J. MacFarlane The Crag Exposure to the West of the Water 5-6 &7 Tower on Rushmere Heath R. A. D. Markham Marsupites from the Gipping Valley Chalk 6 R. A. D. Markham Note of some Crag fossils in the Museum of the 6 Geology Department of Birmingham University Colin Holcombe Section through junction of Red and Coralline 10-12 Crags, “The Rocks” Ramsholt R. A. D. Markham Note re Hoxne Palaeoliths 14 C. Allen Fossils collected from the London Clay, 1963 19-20 R. A. D. Markham An excavation in the Coralline Crag at 21-23 Tattingstone R. A. D. Markham Waldringfield Crag 24-25 R. A. D. Markham Notes on Weavers Pit, Tuddenham St. Martin 25-27 R. A. D. Markham Acknowledgement and publication details 27 GEOGRAPHIC AND GEOLOGICAL NOTES ON THE IPSWICH DISTRICT By H. E. P. Spencer, F.G.S. East Suffolk has beds of sand and clay deposited during the closing chapters of the series of geological epochs. In the region there are probably the greatest number of formations to be found in any such limited area. Basically everything rests on the Cretaceous chalk laid down over 70 million years ago. Locally there are at least 250' missing of the upper chalk which is represented on the Norfolk shore at Trimingham by the Ostrea lunata zone. -

MAP BOOKLET Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies

MAP BOOKLET to accompany Issues and Options consultation on Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies Local Plan Document Consultation Period 15th December 2014 - 27th February 2015 Suffolk Coastal…where quality of life counts Woodbridge Housing Market Area Housing Market Settlement/Parish Area Woodbridge Alderton, Bawdsey, Blaxhall, Boulge, Boyton, Bredfield, Bromeswell, Burgh, Butley, Campsea Ashe, Capel St Andrew, Charsfield, Chillesford, Clopton, Cretingham, Dallinghoo, Debach, Eyke, Gedgrave, Great Bealings, Hacheston, Hasketon, Hollesley, Hoo, Iken, Letheringham, Melton, Melton Park, Monewden, Orford, Otley, Pettistree, Ramsholt, Rendlesham, Shottisham, Sudbourne, Sutton, Sutton Heath, Tunstall, Ufford, Wantisden, Wickham Market, Woodbridge Settlements & Parishes with no maps Settlement/Parish No change in settlement due to: Boulge Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Bromeswell No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Burgh Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Capel St Andrew Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Clopton No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Dallinghoo Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Debach Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Gedgrave Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Great Bealings Currently working on a Neighbourhood -

Suffolk Coast and Estuaries

Suffolk Coast and Estuaries 1 Southwold and the River Blyth 8 5 Orford and the River Ore 16 Escape the hubbub of this busy, A short walk combining the charms of genteel resort to enjoy the tranquillity Orford with a windswept estuary and of the surrounding marshes a treasure trove of wartime secrets 2 Dunwich Heath and Dunwich 10 6 Melton, Bromeswell and Ufford 18 Strike out across the heather-covered Beyond the tides, wander by the upper heath to Dunwich village, a once mighty reaches of the gently flowing River Deben port now all but lost to the sea 7 Sutton Hoo 20 3 Sizewell and RSPB Minsmere 12 Sweeping views of the River Deben A striking example of industry and Valley coupled with one of the world’s nature co-existing on an isolated greatest archaeological discoveries stretch of coast running from a nuclear power plant to the reedbeds of a 8 Ramsholt and the River Deben 22 protected reserve Rural isolation on the banks of the Deben combined with a seamark church 4 Aldeburgh and the River Alde 14 and popular waterside pub Journey past a giant scallop and black tarred fishermen’s huts to the peaceful 9 Felixstowe 24 marshes and gently twisting River Alde There’s a lot more to Felixstowe than you might imagine: imposing docks, historic fort and restored Edwardian seafront gardens 10 Ipswich town and marina 26 History, priceless works of art, literary heritage and maritime tradition all rolled into one in Suffolk’s county town 11 Pin Mill and the River Orwell 28 A classic estuary walk with an irresistible waterside pub and a dash of smuggling history thrown in for good measure 7 1 SUFFOLK COAST AND ESTUARIES Southwold and the River Blyth Distance 6.5km Time 2 hours Once you have finished exploring the Terrain promenade and footpaths old-world charm of the pier, with your Map OS Landranger 156 or OS Explorer 231 back to the sea turn left along the Access parking at seafront; buses from promenade, passing the colourful beach Lowestoft, Beccles, Norwich and huts, and climb up the steps to St James Halesworth; nearest train station is at Green. -

SUFFOLK. [ KELLY's Smyth Lieut.-Col

368 WOODBRID G E. SUFFOLK. [ KELLY'S Smyth Lieut.-Col. Samuel W., V.D. Fern court, AIde- Amendment Act," John Arnott, Church street, Wood- burgh RS.O . bridge; G. A. Shipman, Quay street, Woodbridge, & Stevenson Frands Seymour esq. B.A., M.P., D.L. Play- Shuckforth Downing, Felixstowe ford Mount, near Woodbridge County Police Station, Theatre street, Alfred Hubbard, Thellusson Col. Arthur John Bethel, Thellusson lodge, superintendent; 1 sergeant & 2 constables Aldeburgh, Saxmundham Fire Brigade Station, Cumberland street, John Fosdike, Varley H. F. esq. Walton chief officer, &; 16 men Vernon-Wentworth Thomas Frederick Charles esq. Black- Inland Revenue Office, 6 Gordon villas, St. John's, Fredk. heath, Aldeburgh RS.O Robert Ellis, officer Whitbread Col. Howard C.B., D.L. Loudham park Public Lecture Hall, St. John's street, John W. Andrews, White Robart Eaton esq. Boulge hall, Woodbridge hon. sec Whitmore Wm. N. esq. Snowden hill, Wickham Market Seckford Dispensary, Seckford street, Elphinstone Hollis Wilson Frede'rick W. esq. M.P. Highrow, Fe1ixstowe R.S.O M.D., C.M. surgeon; Anthony Alfred Henley L.RC.P. Youell Edward Pitt, Beacon hill, Martlesham, Woodbridge Edin. consulting surgeon The Chairmen, for the time being, of the Woodbridge Seckford Free Library, Seckford street, Miss Harriet Urban &; Rural Councils are ex-officio magistrates Churchyard, librarian Clerk to the Magistrates, Frands John W. Wood, Seckford Hospital & Woodbridge Endowed Schools, Fras. Church street John Woodhouse Wood, clerk &; solicitor, Seckford st. Petty Sessions are held every thursday in the Woodbridge Shire hall, at 1.0 p.m. The following places are Seckford Reading Room & Social Club, Seckford street, included in the petty sessional division :-Aldeburgh, George Gough, hon. -

East Suffolk Parliamentary Constituencies

East Suffolk - Parliamentary Constituencies East Suffolk Council Scale Crown Copyright, all rights reserved. Scale: 1:70000 0 800 1600 2400 3200 4000 m Map produced on 26 November 2018 at 10:55 East Suffolk Council LA 100019684 Lound CP Somerleyton, Ashby and Herringfleet CP Corton Blundeston CP Flixton CP Oulton CP Lowestoft Oulton Broad Carlton Colville CP Barnby CP Beccles CP Mettingham CP Worlingham CP North Cove CP Shipmeadow CP Barsham CP Bungay CP Mutford CP Gisleham CP St. John, Ilketshall CP Rushmere CP Ellough CP Ringsfield CP Weston CP Kessingland CP Flixton CP Waveney Constituency St. Andrew, Ilketshall CP Henstead with Hulver Street CP Willingham St. Mary CP St. Mary, South Elmham Otherwise Homersfield CP St. Margaret, Ilketshall CP St. Lawrence, Ilketshall CP Sotterley CP St. Peter, South Elmham CP Redisham CP Shadingfield CP St. Margaret, South Elmham CP Benacre CP St. Cross, South Elmham CP St. Michael, South Elmham CP Wrentham CP All Saints and St. Nicholas, South Elmham CP Brampton with Stoven CP Rumburgh CP Frostenden CP Covehithe CP Westhall CP Spexhall CP St. James, South Elmham CP Uggeshall CP South Cove CP Wissett CP Sotherton CP Holton CP Wangford with Henham CP Chediston CP Reydon CP Linstead Parva CP Blyford CP Halesworth CP Linstead Magna CP Southwold CP Cookley CP Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet CP Cratfield CP Huntingfield CP Walberswick CP Blythburgh CP Walpole CP Bramfield CP Thorington CP Ubbeston CP Heveningham CP Dunwich CP Darsham CP Sibton CP Peasenhall CP Westleton CP Yoxford CP Dennington CP Badingham CP Middleton CP Bruisyard CP Rendham CP Saxtead CP Kelsale cum Carlton CP Cransford CP Theberton CP Swefling CP Leiston CP Framlingham CP Earl Soham CP Saxmundham CP Central Suffolk & North Ipswich Great Glemham CP Kettleburgh CP Constituency Benhall CP Knodishall CP Brandeston CP Parham CP Sternfield CP Aldringham cum Thorpe CP Stratford St. -

Ramsholt to Bawdsey Quay

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: Felixstowe Ferry to Bawdsey Report FFB 6: Ramsholt to Bawdsey Quay Part 6.1: Introduction Start Point: Ramsholt (grid reference: TM3088 4141) End Point: Bawdsey Quay (grid reference: TM3312 3788) Relevant Maps: FFB 6a to FFB 6c 6.1.1 This is one of a series of linked but legally separate reports published by Natural England under section 51 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, which make proposals to the Secretary of State for improved public access along and to this stretch of coast between Felixstowe Ferry and Bawdsey. 6.1.2 This report covers length FFB 6 of the stretch, which is the coast between Ramsholt and Bawdsey Quay. It makes free-standing statutory proposals for this part of the stretch, and seeks approval for them by the Secretary of State in their own right under section 52 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. 6.1.3 The report explains how we propose to implement the England Coast Path (“the trail”) on this part of the stretch, and details the likely consequences in terms of the wider ‘Coastal Margin’ that will be created if our proposals are approved by the Secretary of State. Our report also sets out: any proposals we think are necessary for restricting or excluding coastal access rights to address particular issues, in line with the powers in the legislation; and any proposed powers for the trail to be capable of being relocated on particular sections (“roll- back”), if this proves necessary in the future because of coastal change. -

Felixstowe Peninsula Area Action Plan

Introduction Felixstowe Peninsula Area Action Plan Development Plan Document January 2017 Introduction Table of Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 2. Vision and Objectives for Felixstowe Peninsula AAP ...................................................... 12 3. Housing ............................................................................................................................ 17 4. Employment .................................................................................................................... 48 5. Retail ................................................................................................................................ 58 6. Tourism and Sea Front..................................................................................................... 70 7. Environment .................................................................................................................... 84 8. Other Issues ..................................................................................................................... 92 9. Delivery and Monitoring .................................................................................................. 95 Appendix 1 “Saved” Policies to be replaced or deleted ........................................................ 115 Appendix 2 Core Strategy Policy Overview ........................................................................... 116 Appendix -

East Suffolk Council Martello Tower

EAST SUFFOLK COUNCIL MARTELLO TOWER ‘Z’ ALDERTON Grid Reference TM 361 419 List Grade II and Scheduled Ancient Monument Conservation Area No Description Martello Tower. Built c.1810-12 as part of defence line against threat of invasion by Napoleon. Brick with ashlar dressings. Three storeys. Teardrop shaped plan. Suggested Use Risk Priority C Condition Poor Reason for Risk Outer brick skin is peeling away, leaving about 40% of inner structure exposed. First on Register 1997 Owner/Agent Exors of D R Mann. Agent: P J Mann, High House, Bawdsey, Woodbridge IP12 3AW Current Availability Not for sale Notes The owners are investigating potential users or uses for the building in order to facilitate essential repair/conservation works. The area around the tower is no longer in cultivation. On the English Heritage Register of Buildings at Risk. Contact Robert Scrimgeour 01394 444616 EAST SUFFOLK COUNCIL CHAPEL, BAWDSEY MANOR BAWDSEY Grid Reference TM 333 382 List Grade Curtilage building to Bawdsey Manor (II*) Conservation Area No Description A pre-fabricated timber-framed building with corrugated metal covering, consisting of a porch, nave and chancel. Suggested Use Risk Priority A Condition Very bad Reason for Risk Lack of general maintenance has led to decay of timber frame and floor. First on Register 2009 Owner/Agent Mr B Toettcher, Bawdsey Manor, Bawdsey, Woodbridge IP12 3AZ Current Availability Not for sale Notes The chapel was erected by Sir Cuthbert Quilter for use by the Estate workers, c.1900 and is of considerable interest as a privately commissioned and run chapel. Contact Robert Scrimgeour 01394 444616 EAST SUFFOLK COUNCIL LEMONARY 40M N OF BAWDSEY MANOR BAWDSEY Grid Reference TM 337 379 List Grade II Conservation Area No Description Timber-framed glasshouse used as a lemonary. -

Memorials of Old Suffolk

I \AEMORIALS OF OLD SUFFOLK ISI yiu^ ^ /'^r^ /^ , Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldsuOOreds MEMORIALS OF OLD SUFFOLK EDITED BY VINCENT B. REDSTONE. F.R.HiST.S. (Alexander Medallitt o( the Royal Hul. inK^ 1901.) At'THOB or " Sacia/ L(/* I'm Englmnd during th* Wmrt »f tk* R»ut,- " Th* Gildt »nd CkMHtrUs 0/ Suffolk,' " CiUendar 0/ Bury Wills, iJS5-'535." " Suffolk Shi^Monty, 1639-^," ttc. With many Illustrations ^ i^0-^S is. LONDON BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.G. AND DERBY 1908 {All Kifkts Rtterifed] DEDICATED TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE Sir William Brampton Gurdon K.C.M.G., M.P., L.L. PREFACE SUFFOLK has not yet found an historian. Gage published the only complete history of a Sufifolk Hundred; Suckling's useful volumes lack completeness. There are several manuscript collections towards a History of Suffolk—the labours of Davy, Jermyn, and others. Local historians find these compilations extremely useful ; and, therefore, owing to the mass of material which they contain, all other sources of information are neglected. The Records of Suffolk, by Dr. W. A. Copinger shews what remains to be done. The papers of this volume of the Memorial Series have been selected with the special purpose of bringing to public notice the many deeply interesting memorials of the past which exist throughout the county; and, further, they are published with the view of placing before the notice of local writers the results of original research. For over six hundred years Suffolk stood second only to Middlesex in importance ; it was populous, it abounded in industries and manufactures, and was the home of great statesmen. -

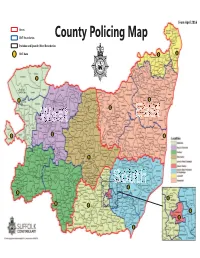

County Policing Map

From April 2016 Areas Somerleyton, Ashby and Herringfleet SNT Boundaries County Policing Map Parishes and Ipswich Ward Boundaries SNT Base 17 18 North Cove Shipmeadow Ilketshall St. John Ilketshall St. Andrew Ilketshall St. Lawrence St. Mary, St. Margaret South Ilketshall Elmham, Henstead with Willingham St. May Hulver Street St. Margaret, South Elmham St. Peter, South ElmhamSt. Michael, South Elmham HomersfieldSt. Cross, South Elmham All Saints and 2 St. Nicholas, South Elmham St. James, South Elmham Beck Row, Holywell Row and Kenny Hill Linstead Parva Linstead Magna Thelnetham 14 1 Wenhaston with Mildenhall Mells Hamlet Southwold Rickinghall Superior 16 Rickinghall Inferior Thornham Little Parva LivermLivermore Ixworthxwo ThorpeThorp Thornham Magna Athelington St.S GenevieveFornhamest Rishangles Fornham All Saints Kentford 4 3 15 Wetheringsett cum Brockford Old Newton Ashfield cum with Thorpe Dagworth Stonham Parva Stratford Aldringham Whelnetham St. Andrew Little cum Thorpe Brandeston Whelnetham Great Creeting St. Peter Chedburgh Gedding Great West Monewden Finborough 7 Creeting Bradfield Combust with Stanningfield Needham Market Thorpe Morieux Brettenham Little Bradley Somerton Hawkedon Preston Kettlebaston St. Mary Great Blakenham Barnardiston Little BromeswellBrome Blakenham ut Sutton Heath Little Little 12 Wratting Bealings 6 Flowton Waldringfield Great 9 Waldingfield 5 Rushmere St. Andrew 8 Chattisham Village Wenham Magna 11 Stratton Hall 10 Rushmere St. Andrew Town Stratford Trimley St. Mary St. Mary 13 Erwarton Clare Needham Market Sproughton Melton South Cove Bedingfi eld Safer Neighbourhood Cowlinge Nettlestead Stoke-by-Nayland Orford Southwold Braiseworth Denston Norton Stratford St. Mary Otley Spexhall Brome and Oakley Teams and parishes Depden Offton Stutton Pettistree St. Andrew, Ilketshall Brundish Great Bradley Old Newton with Tattingstone Playford St.