Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Brom Ebook

THE ART OF BROM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gerald Brom,John Fleskes,Arnie Fenner | 210 pages | 10 Oct 2013 | Flesk Publications | 9781933865492 | English | Santa Cruz, United States The Art of Brom PDF Book Sign up now. The Art Of Gerald Br Lynne Pickering ;Art and Interiors. Beach Art. Reward no longer available 1 backer. Log in Sign up. Your name will be listed in a special thank you page of the book. Skirt Drawing. Learn about new offers and get more deals by joining our newsletter. Rose Drawing Realistic. Accept all Manage Cookies. Includes an extra pages not found in the trade edition. This sumptuous coffee table book weaves together poetry, literature, culture, and art to illuminate the Brom Painting. Eucalyptus Leaves Drawing. Imagery from the Bird's Home: The Art of. Full color fine art representations throughout the large format volume. John Fleskes is the president and publisher of Flesk Publications. Product Details About the Author. Gerald Brom - Brom P Are you happy to accept all cookies? Mean Jellybean Brom Painting Of Womans Face. Bonnard World of Art. Caduceus Drawing. About the Author At age twenty, Brom began working full-time as a commercial illustrator in Atlanta, Georgia. He has since gone on to lend his distinctive vision to all facets of the creative industries, from novels and games, to comics and film. Brom has collected together the very best of his art spanning his 30 year career. Dispatched from the UK in 2 business days When will my order arrive? Also included is the 5. His head is constantly Art Of Brom - Brom P Free delivery worldwide. -

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

Fantastic Art Revisited: Exhibiting Old Masters & Contemporary Art

Fantastic Art Revisited: Exhibiting Old Masters & Contemporary Art A symposium presented by Nicholas Hall and Yuan Fang in conjunction with the exhibition at David Zwirner Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art Saturday Afternoon October 27, 2018 The Kitchen 512 W 19th Street, New York RSVP required for entry. Please email [email protected] or telephone +1 212-772-9100 Please arrive promptly as no one shall be seated once the presentation begins Fantastic Art Revisited: Exhibiting Old Masters and Contemporary Art is a symposium organized by Nicholas Hall and Yuan Fang, to take place on the closing day of the accompanying exhibition Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art at David Zwirner. The symposium brings into focus the legacy of Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s 1936 MoMA exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. A key point of reference for Endless Enigma, Barr’s exhibition brought art by Dada and Surrealist artists into the context of what he called ‘fantastic art’ by European Old Masters, whose works displayed unexpected thematic and formal relationships with those of the avant- garde. It was, in fact, one of the earliest modern museum exhibitions to explore the continuous conversation between art of the past and art of the present – a dialogue that has enjoyed increasing popularity in recent years across the museum and commercial art world. The half-day event will consist of presentations by curators and academics from leading European and American institutions. Divided into two sessions, the presentations will cover a diverse range of topics referencing a single work, subject or concept touched upon in Endless Enigma; the first session explores the earlier history of fantastic art, while the following session presents topics pertaining to museology and display. -

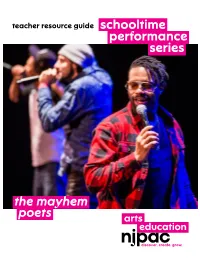

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

1-54 FORUM Talks Programme Announced for Second Edition in Marrakech, Curated by Art Historian and Curator Karima Boudou

1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair La Mamounia, Marrakech, 23 – 24 February 2019 1-54 FORUM talks programme announced for second edition in Marrakech, curated by art historian and curator Karima Boudou • Twelfth edition of 1-54 FORUM, titled ‘Let’s Play Something Let’s Play Anything Let’s Play’1, will examine narratives of surrealism in Africa and its diaspora • Conversation on Ted Joans’ relationship with surrealism by lecturer Joanna Pawlik • Screenings of work by filmmakers Kara Walker and Louis Van Gasteren • Panel discussions on the contemporary use of sound and language to liberate the unconscious and document it • Talk on Maghrebian Surrealism and the Surrealist movement in Egypt L-R: Noureddine Ezarraf, The Public Writer, 2017, installation. Photo by Lisa Stewart of Queens Collective. Courtesy the artist; Vince Fraser, BLAQUE MATISSE, 2017. Courtesy the artist; Abdellah Hassak, Alarme! Alarme! Alarme!, 2016. Courtesy the artist. 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, the leading international art fair dedicated to contemporary African art, has announced details of 1-54 FORUM, the fair’s acclaimed talks and events programme, for the second Marrakech edition in February. Curated for the first time by art historian and curator, Karima Boudou, the programme entitled ‘Let’s Play Something Let’s Play Anything Let’s Play’ will take place during the fair at La Mamounia. In addition, 1-54 FORUM will host three sessions around the city at ESAV (L'École Supérieure des Arts Visuels de Marrakech), Musée Yves Saint Laurent Marrakech and Le 18, a multidisciplinary art space. 1-54 Marrakech 2019 will present 18 leading galleries from 11 countries featuring more than 65 artists from Africa and its diaspora. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

The Essence of Fantasy Art

The Essence of Fantasy Art Find your creative power and reach the top of your favorite art field Stefan Loå To all of you who create a beautiful world. The Essence of Fantasy Art First published in 2015 by Mikronisch LM Ericssons väg 26 126 26 Hägersten Sweden Copyright © 2015 Stefan Loå Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-91-637-7627-4 All rights reserved. No part of this work - except minor sections - may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Applications for the copyright holders written permissions to reproduce and part of this publication should be addressed to the publishers. Contents Introduction ................................................................................. 1 Chapter One: Learning the very basics ........................................ 7 Chapter Two: Finding the top 1 % .............................................11 Chapter Three: Give it all you have – or cut off your finger ..... 15 Chapter Four: Fantasy and Magic ��������������������������������������������� 19 Chapter Five: Your inner goldmine ...........................................27 Chapter Six: My secret tricks �����������������������������������������������������33 Chapter Seven: Inner passion ................................................... 41 Chapter Eight: Try or TRY ���������������������������������������������������������45 Chapter Nine: The big exercise -

The University of Delaware Library Is in the Process of Converting Its

The University of Delaware Library is in the process of converting its legacy HTML, PDF, and word processed finding aids into Encoded Archival Description (EAD) and migrating them into a new XTF-based delivery system. During this conversion many finding aids will direct you to an older version of the Special Collections website. For additional information, please contact Special Collections at: http://library.udel.edu/spec/askspec/ Special Collections University of Delaware Library 181 South College Avenue Newark, DE 19717-5267 USA (302) 831-2229 Charles Henri Ford Letters to Ted Joans 1964 - 1987 (bulk dates 1964-1965, 1975-1987) Manuscript Collection Number 292 Accessioned: Purchase, 1993. Extent: 55 items (.1 linear ft.) Content: Letters, posters, brochures, announcements, clippings, and poems. Access: The collection is open for research. Processed: January 1994 by Anita A. Wellner. Biographical Notes Charles Henri Ford Poet, artist, filmmaker, and editor, Charles Henri Ford was born on February 10, 1913, in Brookhaven, Mississippi. In 1929, having dropped out of high school, Ford began his literary career as co-editor, with Parker Tyler, of Blues: a magazine of new rhythms (1929-1930). Published in Columbus, Mississippi, this literary magazine showcased the new schools of modern art and literature, publishing such contemporary writers as Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams, Erskine Caldwell, Ezra Pound, and e. e. cummings. By 1931 Charles Henri Ford had left the United States for France, the beginning of his world travels. During his first few years abroad, Ford wrote his only novel, the classic The Young and the Evil (Obelisk, 1933). Since that time, Ford has lived in Morocco, Italy, France, Crete, and New York City; and his poetry, films, and artwork have reflected his international travels and multicultural experiences. -

SURREALISM IS a THING RUBRICS and OBJECTIVATION in the SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine Hansen

ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/5/3/62/1832938/artm_a_00158.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 SURREALISM IS A THING RUBRICS AND OBJECTIVATION IN THE SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine hansen What Will Be is the title of a 2014 anthology compiled by members of a 21st-century international network of Surrealist groups, announcing the continuing ambitions of a movement that fi rst began amid the sleeping fi ts and Dada-inspired provocations of the early 1920s. The anthology includes a special feature on the publishing activities of the various groups, which frequently coordinate their efforts across group and national boundaries—operating as a kind of dispersed organism whose vital functions have never seen fi t to cease, even as Surrealism has come to be considered a historical and concluded phenomenon. There is particular emphasis on the Surrealist attitude, in general, toward publishing, publicization, circulation, the digital revolution, and the rise of on-demand printing. Contributors, for example, speak- ing on behalf of the Montreal- and Miami-based Surrealist publisher Editions Sonámbula, state: “any attempt aiming to expand the fi eld of the real and of the poetic has necessarily to refl ect on the means of communication to use.”1 Surrealism has always claimed to extend the domain of what is 1 “The Utility of Surrealist Editions and of the Surrealist Gallery: An Inquiry,” in Ce qui sera/What Will Be/Lo que serà: Almanac of the International Surrealist Movement, “hors- série” number of Brumes Blondes, ed. Her de Vries and Laurens Vancrevel (Amsterdam: Brumes Blondes, 2014), 438–39. -

SFRA Newsletter 169 Ouly-August 1989): 14-16

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 4-1-1999 SFRA ewN sletter 239 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 239 " (1999). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 58. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/58 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #1a. APRIL 1### CoedHors: lIonljdjon Reyjew EdHor: Karen Hellekson & Crajl Jacobsen lIejl Barron • ~ • ~I .. .:. [;) CYBERSPACE PATROL Alan Elms Cyberspace fictions continue to be of considerable interest to SFRA members; note for instance the twenty pages on "Approaching Neuromancer" in the February issue of the SFRAReview. Until recently, SFRA itself has been nearly invisible in cyberspace-but no more! First, Peter Sands has been working to expand the scope and content of the official SFRA Web page, with the help of vice president Adam Frisch and oth ers. If you haven't visited our Web page in the past few weeks, give it a try at <http://www.uwm.edu/~sands/sfralscifi.htm>. (If you bookmarked the page ear lier, you may be using an old address that leads to an earlier version; replace it with the address above.) By the time you read this, we may have been able to obtain an address that's easier to remember: <http://www.sfra.org>. -

News Flashes from Our Members

PITTSBURGH SOCIETY OF ILLUSTRATORS NEWS AND EVENTS www.pittsburghillustrators.org September, 2010 My Spot by Anni Matsick News Flashes From Our Members Whenever I sign up for a Month by Month Eye Popping Prints conference, Aries and others ask if Pisces I expect to are two “get any work more from it.” Some pages may, but I’ve from attended John many national and some regional con- Blumen’s ferences over the years and can’t say ongoing that a single assignment has resulted calendar directly from my attending. I can say, project. however, that each experience affect- ed my career as an illustrator and my personal life in many other ways, some educational, some social. The con- nections made and wisdom gathered can be put to use toward sharpening your skills and getting acquainted with others who share the same interests; things that can lead to more work. If you aren’t already signed up for PSIcon you can do that now, online, at These pittsburghillustrators.org two new silkscreen Don’t let our society’s first major all- prints illustration event go by without YOU by Tim being involved! Next issue, we’ll look Oliveira, back on photos and coverage and “Thirsty” allow you to share your own com- and ments on the experience. Enrollment “Sunbeam” has already attracted a number of new are avail- members who recognize the value. able for Come, be entertained, informed, even sale on pampered (with breakfast and lunch)! his new Then, for the next issue, tell us all website about it! at: www.timoliveira.com Both are 18” x 24” signed and editioned 5-color serigraphs.