I Was a Poet, I Was Young”: a Reconsideration of the Georgian Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

Copyright by Deborah Helen Garfinkle 2003

Copyright by Deborah Helen Garfinkle 2003 The Dissertation Committee for Deborah Helen Garfinkle Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Bridging East and West: Czech Surrealism’s Interwar Experiment Committee: _____________________________________ Hana Pichova, Supervisor _____________________________________ Seth Wolitz _____________________________________ Keith Livers _____________________________________ Christopher Long _____________________________________ Richard Shiff _____________________________________ Maria Banerjee Bridging East and West: Czech Surrealism’s Interwar Experiment by Deborah Helen Garfinkle, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 For my parents whose dialectical union made this work possible ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express heartfelt thanks to my advisor Hana Pichova from the University of Texas at Austin for her invaluable advice and support during the course of my writing process. I am also indebted to Jiří Brabec from Charles University in Prague whose vast knowledge of Czech Surrealism and extensive personal library provided me with the framework for this study and the materials to accomplish the task. I would also like to thank my generous benefactors: The Texas Chair in Czech Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, The Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin, The Fulbright Commission and the American Council of Learned Societies without whom I would not have had the financial wherewithal to see this project to its conclusion. And, finally, I am indebted most of all to Maria Němcová Banerjee of Smith College whose intelligence, insight, generosity as a reader and unflagging faith in my ability made my effort much more than an exercise in scholarship; Maria, working with you was a true joy. -

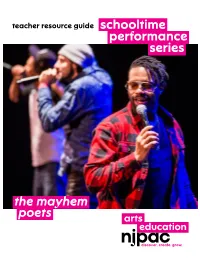

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

PDF the Migration of Literary Ideas: the Problem of Romanian Symbolism

The Migration of Literary Ideas: The Problem of Romanian Symbolism Cosmina Andreea Roșu ABSTRACT: The migration of symbolists’ ideas in Romanian literary field during the 1900’s occurs mostly due to poets. One of the symbolist poets influenced by the French literature (the core of the Symbolism) and its representatives is Dimitrie Anghel. He manages symbols throughout his entire writings, both in poetry and in prose, as a masterpiece. His vivid imagination and fantasy reinterpret symbols from a specific Romanian point of view. His approach of symbolist ideas emerges from his translations from the French authors but also from his original writings, since he creates a new attempt to penetrate another sequence of the consciousness. Dimitrie Anghel learns the new poetics during his years long staying in France. KEY WORDS: writing, ideas, prose poem, symbol, fantasy. A t the beginning of the twentieth century the Romanian literature was dominated by Eminescu and his epigones, and there were visible effects of Al. Macedonski’s efforts to impose a new poetry when Dimitrie Anghel left to Paris. Nicolae Iorga was trying to initiate a new nationalist movement, and D. Anghel was blamed for leaving and detaching himself from what was happening“ in the” country. But “he fought this idea in his texts making ironical remarks about those“The Landwho were” eagerly going away from native land ( Youth – „Tinereță“, Looking at a Terrestrial Sphere” – „Privind o sferă terestră“, a literary – „Pământul“). Babel tower He settled down for several years in Paris, which he called 140 . His work offers important facts about this The Migration of Literary Ideas: The Problem of Romanian Symbolism 141 Roșu: period. -

Discovering Rupert Brooke Grantchester Dymock

Just after their 21st wedding anniversary, for the first time since Christmas, David Maxwell Fyfe managed to get back to London to be with his wife and their family for a weekend over Easter. It was an extremely welcome reunion, as it was two months since they had been together, when Sylvia visited him in Nuremberg, and the time spent apart was growing more difficult for them both as there was still no clear end in sight for the trial. David Maxwell Fyfe 11th April 1946 Keitel is finished and Kaltenbrunner has ‘taken the stand’ I have nothing to do with him and am hoping violently that the Americans will do a good job. Ernst Kaltenbrunner was the highest-ranking member of the SS to face trial at Nuremberg. As Chief of the Main Security Office from 1943 - 45 he answered to Heinrich Himmler, overseeing a period in which persecution of Jews intensified. He is considered a major perpetrator of the Holocaust during the final years of the war. David Maxwell Fyfe 11th April 1946 I cannot realise that I am going to get home a week from today. It will be absolutely marvellous. Sylvia Maxwell Fyfe 14th April 1946 If it is any pleasure to you to know this is the first year out of 21 that I have not enjoyed. It ought to make you rather conceited if that were possible. Anyway I shall adore my Easter - and all things come to an end - even Nuremberg trials I suppose though I confess I sometimes doubt it. There was very little let up from the relentless strain of the trial, now in its’ sixth month, or genuine relaxation in the company of his equally tired work colleagues. -

Paris and Havana: a Century of Mutual Influence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Paris and Havana: A Century of Mutual Influence Laila Pedro Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/264 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Paris and Havana : A Century of Mutual Influence by LAILA PEDRO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in French in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 LAILA PEDRO All Rights Reserved i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in French in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mary Ann Caws 04/22/2014 Date Chair of Examining Committee Francesca Canadé Sautman 04/22/2014 Date Executive Officer Mary Ann Caws Oscar Montero Julia Przybos Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract PARIS AND HAVANA: A CENTURY OF MUTUAL INFLUENCE by Laila Pedro Adviser: Mary Ann Caws This dissertation employs an interdisciplinary approach to trace the history of exchange and influence between Cuban, French, and Francophone Caribbean artists in the twentieth century. I argue, first, that there is a unique and largely unexplored tradition of dialogue, collaboration, and mutual admiration between Cuban, French and Francophone artists; second, that a recurring and essential theme in these artworks is the representation of the human body; and third, that this relationship ought not to be understood within the confines of a single genre, but must be read as a series of dialogues that are both ekphrastic (that is, they rely on one art-form to describe another, as in paintings of poems), and multi-lingual. -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

Open Ikuho Amano Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Comparative Literature ASCENDING DECADENCE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF DILEMMAS AND PLEASURES IN JAPANESE AND ITALIAN ANTI-MODERN LITERARY DISCOURSES A Thesis in Comparative Literature by Ikuho Amano © 2007 Ikuho Amano Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2007 ii The thesis of Ikuho Amano was reviewed and approved* by the following: Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Japanese Thesis Adviser Chair of Committee Thomas O. Beebee Professor of Comparative Literature and German Véronique M. Fotí Professor of Philosophy Maria R. Truglio Assistant Professor of Italian Caroline D. Eckhardt Professor of Comparative Literature and English Head of the Department of Comparative Literature _________________________ * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii Abstract This dissertation examines the significance of the notion of “decadence” within the historical framework of Modernism, especially in Italy and Japan, which were latecomers to modernity. In contrast to the major corpus of fin-de-siècle Decadence, which portrays decadence fundamentally as the subjectively constructed refutation of modern material and cultural conditions, the writers of decadent literature in Italy and Japan employ the concept of decadence differently in their process of rendering the modern self and subjectivity in literary discourse. While mainstream fin-de-siècle Decadence generally treats the subject as an a priori condition for its aesthetics, these writers on modernity’s periphery incorporate heterogeneous spectrums of human consciousnesses into their narratives, and thereby express their own perspectives on the complexities inherent in the formation of modern subjectivity. -

Refrain, Again: the Return of the Villanelle

Refrain, Again: The Return of the Villanelle Amanda Lowry French Charlottesville, VA B.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1992, cum laude M.A., Concentration in Women's Studies, University of Virginia, 1995 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August 2004 ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ABSTRACT Poets and scholars are all wrong about the villanelle. While most reference texts teach that the villanelle's nineteen-line alternating-refrain form was codified in the Renaissance, the scholar Julie Kane has conclusively shown that Jean Passerat's "Villanelle" ("J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle"), written in 1574 and first published in 1606, is the only Renaissance example of this form. My own research has discovered that the nineteenth-century "revival" of the villanelle stems from an 1844 treatise by a little- known French Romantic poet-critic named Wilhelm Ténint. My study traces the villanelle first from its highly mythologized origin in the humanism of Renaissance France to its deployment in French post-Romantic and English Parnassian and Decadent verse, then from its bare survival in the period of high modernism to its minor revival by mid-century modernists, concluding with its prominence in the polyvocal culture wars of Anglophone poetry ever since Elizabeth Bishop’s "One Art" (1976). The villanelle might justly be called the only fixed form of contemporary invention in English; contemporary poets may be attracted to the form because it connotes tradition without bearing the burden of tradition. Poets and scholars have neither wanted nor needed to know that the villanelle is not an archaic, foreign form. -

In Search of God: the Lost Horizon in Rupert Brooke's Poetry

In Search of God: The Lost Horizon in Rupert Brooke’s Poetry Mohamed Ahmed Mustafa Al-Laithy (Ph.D.) Assistant Professor of English Al-Imam Muhammad Bin Sad Islamic University Riyadh Saudi Arabia I The British poet Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) is one of the poets who should be reread and reassessed. Brooke‟s reputation as a poet has been very much apt to doubt and controversies by admirers and detractors alike. Unlike many other poets, Brooke prospered greatly as a poet when he was only twenty. At his time, he was a “poetic…model” (Willdhardt, 49). Unlike the majority of poets, again, shortly after his death at the age of twenty eight, his reputation declined drastically and his poetry was vehemently criticised, attacked and undervalued. This makes of Brooke a unique phenomenon worthy of rereading and reassessment. Indeed, what happened with Brooke as a poet is exactly the opposite of what usually happens with poets during their lifetimes and after their deaths. One can just think of such poets as John Keats (1795-1821)and Alfred Tennyson (1809-92) and Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) who were severely attacked during their lifetimes, but were explored and championed after their deaths. Ever since the 1920s and the 1930s of the past century, Brooke‟s name as a poet has been diminishing, and almost vanishing, indeed. There seems to have been a general consent among writers and critics of one generation after another either to mention the poet askance, undervalue his poetic contribution, or else to ignore him totally. To give one example, The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, one of the most prestigious, referential anthologies in English, mentions nothing at all about Brooke or his poetry. -

SURREALISM IS a THING RUBRICS and OBJECTIVATION in the SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine Hansen

ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/5/3/62/1832938/artm_a_00158.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 SURREALISM IS A THING RUBRICS AND OBJECTIVATION IN THE SURREALIST PERIODICAL, 1924–2015 Catherine hansen What Will Be is the title of a 2014 anthology compiled by members of a 21st-century international network of Surrealist groups, announcing the continuing ambitions of a movement that fi rst began amid the sleeping fi ts and Dada-inspired provocations of the early 1920s. The anthology includes a special feature on the publishing activities of the various groups, which frequently coordinate their efforts across group and national boundaries—operating as a kind of dispersed organism whose vital functions have never seen fi t to cease, even as Surrealism has come to be considered a historical and concluded phenomenon. There is particular emphasis on the Surrealist attitude, in general, toward publishing, publicization, circulation, the digital revolution, and the rise of on-demand printing. Contributors, for example, speak- ing on behalf of the Montreal- and Miami-based Surrealist publisher Editions Sonámbula, state: “any attempt aiming to expand the fi eld of the real and of the poetic has necessarily to refl ect on the means of communication to use.”1 Surrealism has always claimed to extend the domain of what is 1 “The Utility of Surrealist Editions and of the Surrealist Gallery: An Inquiry,” in Ce qui sera/What Will Be/Lo que serà: Almanac of the International Surrealist Movement, “hors- série” number of Brumes Blondes, ed. Her de Vries and Laurens Vancrevel (Amsterdam: Brumes Blondes, 2014), 438–39. -

RUPERT BROOKE 1887-1915 the Soldier

http://www.englishworld2011.info/ BROOKE: THE SOLDIER / 1955 but thirteen or so / I went into a golden land, / Chimporazo, Cotopaxi / Took me by the hand"). Sometimes the magical note was authentic, as in many of Walter de la Mare's poems, and sometimes the meditative strain was original and impressive, as in Edward Thomas's poetry. But as World War I went on, with more and more poets killed and the survivors increasingly disillusioned, the whole world on which the Georgian imagination rested came to appear unreal. A patriotic poem such as Rupert Brooke's "The Soldier" became a ridiculous anachronism in the face of the realities of trench warfare, and the even more blatantly patriotic note sounded by other Geor- gian poems (as in John Freeman's "Happy Is England Now," which claimed that "there's not a nobleness of heart, hand, brain / But shines the purer; happiest is England now / In those that fight") seemed obscene. The savage ironies of Siegfried Sassoon's war poems and the combination of pity and irony in Wilfred Owen's work portrayed a world undreamed of in the golden years from 1910 to 1914. World War I left throughout Europe a sense that the bases of civilization had been destroyed, that all traditional values had been wiped out. We see this sense reflected in the years immediately after the war in different ways in, for example, T. S. Eliot's Waste Land and Aldous Huxley's early fiction. But the poets who wrote during the war most directly reflected the impact of the war experience.