Not the Apocalypse: Television Futures in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. These changes have affected the cost-benefit calculations of media ownership and led to the entrance of Chinese capital into the Hong Kong media scene. The digital media arena is also facing the challenge of intrusion by the state. KEYWORDS: press freedom, political economy, self-censorship, digital media, media business, Hong Kong. wo decades after the handover, many observers, academics, and jour- part follows past scholarship to outline the ownership structure of the Hong nalists would agree that press freedom in Hong Kong has declined over Kong media system, while noting how several counteracting forces have Ttime. The titles of the annual reports by the Hong Kong Journalists As- prevented the media from succumbing totally to political power. -

Channel U

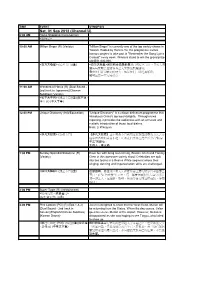

TIME EVENT SYNOPSIS Sat, 01 Sep 2012 (Channel U) 6:00 AM Home Shopping (Commercial) <购物乐> 10:00 AM Million Singer (R) (Variety) "Million Singer" is currently one of the top variety shows in Taiwan. Hosted by Harlem Yu, the programme invites famous singers to take part in "Remember the Song Lyrics Contest" every week. Winners stand to win the grand prize of NT$1,000,000. <百万大歌星> (综艺节目)(重) <百万大歌星>是目前台湾最新最热门的综艺节目。主持人庾 澄庆每期都会邀请许多艺人来参加歌唱游戏, 考验他们背记歌词的功力。如果他们一路过关斩将, 就可赢取一百万元奖金。 11:30 AM Wonders of Horus (R) (Dual Sound - 2nd track in Japanese)(Chinese Subtitles) (Variety) <科学大不同> (综艺节目)(重)(双声道 - 华日语) (中文字幕) 12:00 PM Unique Discovery (Info/Education) "Unique Discovery" is a unique delicacies programme that introduces China's top local delights. Through news reporting, it provides the audiences with an accurate and realistic introduction of these local dishes. Host: Li Wenjuan <非凡大探索> (资讯节目) 《非凡大探索》这个美食节目利用近似新闻报导的方式去介 绍中国各地的美食小吃,让观众们亲身品尝之后少有"报导 不实"的感觉。 主持人:李文娟 1:00 PM Sunday Splendid Showtime (R) Have fun with Zeng Guo Cheng, Blackie Chen and Tammy (Variety) Chen in this awesome variety show! Celebrities are split into two teams in a Red vs White segment where their singing, dancing and impersonation skills are challenged. <周日大精彩> (综艺节目)(重) 由曾国城、陈建州(黑人)和陈怡蓉主持的娱乐性丰富综艺 节目。在"红白大赏"单元里,每一集曾国城和黑人会分别带 领一班艺人,在舞蹈、歌唱、模仿等各方面互相竞技,争取 胜利。 2:00 PM Super Taste (R) (Infotainment) <时尚玩家 - 就要酱玩> (娱乐资讯节目)(重) 3:00 PM Pink Lipstick (PG) (R) (Eps 1 & 2) Jia'en is delighted to know that her best friend, Meilan will (Dual Sound - 2nd track in be returning from the States. When the day comes, Jia'en Korean)(English/Chinese Subtitles) goes to receive Meilan at the airport. -

Consultation Paper on the Future Directions of the Radio Television

Public Consultation Paper on The New Radio Television Hong Kong: Fulfilling its Mission as a Public Service Broadcaster Commerce and Economic Development Bureau October 2009 Public Consultation Paper on The New Radio Television Hong Kong: Fulfilling its Mission as a Public Service Broadcaster Commerce and Economic Development Bureau October 2009 - 2 - Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 : Preamble 3 Chapter 2 : Public Purposes 6 Chapter 3 : Corporate Governance 9 Chapter 4 : The Charter 14 Chapter 5 : Performance Evaluation 17 Chapter 6 : Extended Mode of Service Delivery 25 Chapter 7 : New Programming Opportunities 26 Chapter 8 : Public Consultation 30 - 3 - CHAPTER ONE PREAMBLE Introduction 1.1 The subject of public service broadcasting (PSB) and the future of Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) have been debated in the community for over 20 years. In January 2006, the Chief Executive (CE) appointed an independent Committee on Review of Public Service Broadcasting (the Review Committee) to examine the subject of PSB. The Review Committee submitted its report to the Government in March 2007. On 22 September 2009, having regard to the Review Committee’s report and all relevant considerations, the Chief Executive in Council (CE in C) decided on the way forward on the development of PSB in Hong Kong. RTHK is to be tasked to take up the mission to serve as the public service broadcaster for Hong Kong, with safeguards and appropriate resources provided to allow it to do so effectively. This momentous decision marks the beginning of a new RTHK, with a new mission and objectives. 1.2 This consultation paper sets out our proposals on how to enhance the role and functions of the new RTHK as a public service broadcaster and seeks views from the public on the implementation measures. -

Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics Interpersonal Meaning

OPEN ACCESS Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics ISSN 2209-0959 https://journals.castledown-puBlishers.com/ajal/ Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1 (1), 3-19 (2018) https://dx.doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v1n1.4 Interpersonal Meaning of Code-switching: An Analysis of Three TV Series WANG HUABIN a a Department of English, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Abstract As one of the most widespread linguistic phenomena, code-switching has attracted increasing attention nowadays. Inspired by previous studies in this field, this paper addresses code-switching under the guidance of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), with the primary goal of analysing the interpersonal meanings of code-switching in three TV series. The research data were collected as follows: first, internet resources were examined to find three popular TV series with code-switching, namely I Not Stupid, Moonlight Resonance and Humble Abode; second, the data were selected, classified and observed for analysis. As the focus of this paper is interpersonal meaning, functional theories were elaborated towards a single framework for interpersonal meanings of code-switching in two parts: appraisal theory and tenor in register. The first part aims to evaluate emotions which are embedded in code-switching. The second part deals with the roles and relationships between different participants. With these theories included in the research, qualitative analyses were conducted: first of all, sample data were categorised based on their grammatical structures; then interpersonal meanings of code-switching are discussed under the guidance of these functional theories to test the applicability of SFL in this field. -

Channel U

TIME EVENT SYNOPSIS Mon, 01 Oct 2012 (Channel U) 11:00 AM Home Shopping (Commercial) <购物乐> 3:00 PM Money Week (R) (Local Current Tung Soo Hua hosts Money Week, the Mandarin Business Affairs) Current Affairs Programme, that provides comprehensive insights and analysis of the business world. <财经追击> (本地时事节目)(重) 《财经追击》是新加坡唯一以中文制作的经济时事节目。节 目将深入分析最新的经济趋势和商业动态,让观众能更好地 掌握市场走势和投资情报。 3:30 PM P.R.D. Walker (R) (Info/Education) In this series of travelogues, host Leung Ka Ki and Karman Cheng takes us through the many interesting places throughout China's Pearl River Delta. <潮游珠三角> (资讯节目)(重) 在这系列旅游记事里, 让主持人梁嘉琪与郑嘉雯带我们潮游珠三角. 4:00 PM The Stories In China (R) Hosted by Cai Li Qun and Ken, "Stories of China" is a fun (Infotainment) and adventurous travelogue that takes its viewers to the different parts of China. From cultural to traditional activities, each episode features the most authentic aspects of China ever as Li Qun shares with the viewers stories about the place visited and its people. <在中国的故事> (娱乐资讯节目)(重) 最真实的中国,最动人的故事! 让节目主持人蔡立群与阿Ken,带大家去见识中国各地多姿 多彩的文化与习俗,品尝各种风味不同的地方美食,以及与 观众分享一些鲜为人知的民间轶事。 5:00 PM Angel Lover (R) (Ep 9) (Taiwan As members of an organisation called "Angel Lover", a Drama) group of five young men devote themselves to helping women, who have troubles in their relationships with men, to rediscover the true meaning of love and to regain confidence in life. <天使情人> (台湾剧)(重) 曾经为爱伤痛的Angelina, 成立了一个名叫"Angel Lover"的组织。这个组织有五个男生, 他们愿意付出自己的关心和智慧, 帮助那些在感情上受过伤害的女人,重新获得爱与生命的勇 气。 6:00 PM Moonlight Resonance (R) (Ep 12) Taizu's mum goes on a hunger strike when Yongzhong (English/Chinese Subtitles) and Yongjia refuse to return home. -

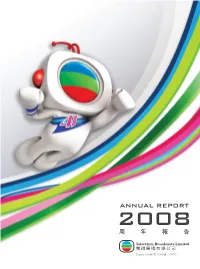

2008 Annual Report

Highlights Turnover & Profit Attributable to Equity 2008 2007 Change Holders of the Company Turnover Profit Attributable to Equity Holders of the Company Financial Highlights Performance 5,000 Earnings per share HK$2.41 HK$2.89 -17% Dividend per share – Interim HK$0.30 HK$0.30 – 4,000 – Final HK$1.40 HK$1.50 -7% HK$1.70 HK$1.80 -6% 3,000 For the year HK$’ mil HK$’ mil Turnover HK$’ mil – Terrestrial television broadcasting 2,346 2,373 -1% 2,000 – Programme licensing and distribution 773 743 +4% – Overseas satellite pay TV operations 289 281 +3% – Channel operations 1,065 965 +10% 1,000 – Other activities 107 101 +6% – Inter-segment elimination (173 ) (137 ) +26% 4,407 4,326 +2% 0 20042005 2006 2007 2008 YEAR Total expenses (3,102 ) (2,787 ) +11% Share of losses of associates (63 ) (125 ) -50% Profit attributable to equity holders 1,055 1,264 -17% Earnings & Dividends Per Share Earnings per Share Dividends per Share As at 31 December Total assets 6,742 6,251 +8% 3.5 Total liabilities 1,108 882 +26% Total equity 5,634 5,369 +5% 3 Number of issued shares 438,000,000 438,000,000 2.5 Ratios Current ratio 5.34 5.42 Gearing 6% – 2 HK$ Operational Highlights 1.5 Average audience share Weekday prime time – Jade 85% 84% 1 Weekly prime time – Pearl 75% 79% 0.5 Number of terrestrial TV channels in Hong Kong 5 * 3 0 20042005 2006 2007 2008 * as of 25 Mar 2009 YEAR 2008 Turnover by Business Segment 2008 Segment Results by Business Segment Terrestrial television Terrestrial television broadcasting 53% (55%) broadcasting 47% (62%) Programme licensing -

João Gilberto

SEPTEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Satellite Television and the Future of Broadcast Television in the Asia Pacific

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Satellite television and the future of broadcast television in the Asia Pacific Wang, Georgette 1993 Wang, G. (1993). Satellite television and the future of broadcast television in the Asia Pacific. In AMIC Conference on Communication, Technology and Development. Alternatives for Asia, Kuala Lumpur, Jun 25‑27, 1993. Singapore: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93089 Downloaded on 30 Sep 2021 14:02:37 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Satellite Television And The Future Of Broadcast Television In The Asia Pacific by Georgette Wang Paper No. 17 ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Satellite Television and the Future of Broadcast Television in the Asia Pacific Georgette Wang Department of Journalism National Chengchi University Taipei, Taiwan, ROC Paper presented at the Conference on Communication, Technology and Development: Alternatives for Asia, Kula Lumpur, Malaysia, June 25-17, 1993. Satellite Television and the Future of Broadcast Television in the Asia Pacific Decades since the first mention of media imperialism and ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library cultural dependency, the proliferation of communication technologies, including satellite television, VCR and cable television has brought renewed concerns over these issues (Servaes, 19**2; Sussman and Lent, 1991). While in majority of the nations broadcast television has seldom ceased to import programs, communication technologies have gone one step further to thoroughly abolish boundaries; racial, cultural or national. -

How the Lion Rock Was Tempered: Early RTHK Dramas, Social Bonding, and Post-1967-Crisis Governance

Fall Symposium on Digital Scholarship 2020 @HKBU October 20, 2020 via Zoom How the Lion Rock Was Tempered: Early RTHK Dramas, Social Bonding, and Post-1967-Crisis Governance Dr. Kwok Kwan Kenny NG Associate Professor, Academy of Film, Hong Kong Baptist University Joy Kam Research Assistant Digital Database: TV Week magazine and movie scripts (1967-1997) Television Viewing Habit, Experience, and Community • Viewing time and viewing ritual • Household and publicness • Moral and social values (‘soft propaganda’) • Hong Kong’s economic takeoff in the 1970s and early 1980s “The shared experience amongst virtually the entire population enjoying the same television programs every day contributed a great deal to the creation of a unified cultural identity for the populace” (Kai-cheung Chan and Po-king Choi) Television in Hong Kong (Karin Gwinn Wilkins) • Commercial factors more than the political, social, or cultural • Laissez-faire; favor private enterprises and free trade • Apolitical and market-driven • Perpetuating a sense of local Hong Kong identity (at times with a larger Chinese community) Commercial Market vs. Public Service (Mark Hampton) • Government unconcerned with television’s cultural potential • Uninterested to promote British values • Not adopting a public service approach • Yet, after the 1967 riots, “the Government took a stronger hand in television, both for directly propagandistic purposes and to regulate it in response to public demands" in order to bridge “the communication ‘gap’ that had apparently developed between the government and people” How could public TV programs promote communication and legitimacy of governance? Lion Rock in the 1970s. Photo credit: Housing Authority Lion Rock in the 2010s. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema.