©2016 Tara Coleman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Modernism and “Cine-Text”: Fragments and Flows at Empire’S Edge in Kitagawa Fuyuhiko and Yokomitsu Riichi

CHAPTER 24 JAPANESE MODERNISM AND “CINE-TEXT”: FRAGMENTS AND FLOWS AT EMPIRE’S EDGE IN KITAGAWA FUYUHIKO AND YOKOMITSU RIICHI WILLIAM O. GARDNER In November 1930, literary critic Inoue Yoshio wrote that the “belief in the eye” evident in Kitagawa Fuyuhiko’s recent poetry had progressed from a faith in the human eye to a belief in “that which is all the more precise, all the more objective: to the machine eye—to the lens” (17).' This critical comment, strongly evocative of Soviet filmmaker and theorist Dziga Vertov’s conception of the “cine-eye” {kinoglaz), builds upon Kitagawas own statement that “the poetry of tomorrow is advancing toward the ‘victory of the eye’” (Usawa 30). As Inoue suggests, Kitaga wa’s poetry circa 1930 displays a tendency to emulate the film camera, rather than the human eye, in presenting objects that are disassociated from the viewpoint of any single subjective viewing position. This aspiration to the free-ranging and “objective” viewpoint of the “machine eye” is part of a broad confluence between the literary and the cinematic in Kitagawa’s work, which we can also identify in his exploration of the poetic genre of the “cinepoeme,” as well as his coinage of the term “prose film” in his later critical and theoretical writings on cinema. As I will 572 TRANSLATION ZONES explore in this essay, Kitagawa’s writings from the 1920s and 1930s, together with the contemporaneous works of prose author Yokomitsu Riichi, are strongly marked by this confluence of the literary and the cinematic—so much so that we might term Kitagawa and Yokomitsu’s writing from this period “cine-text”: literary and critical texts permeated with cinematic qualities and concerns. -

Master for Quark6

Special Feature s e v i a t Realisms within Conundrum c n i e h The Personal and Authentic Appeal in Jia Zhangke’s Accented Films (1) p s c r e ESTHER M. K. CHEUNG p With persistent efforts on constructing personal and collective memories arising from the unprecedented transformations in post-socialist China, Jia Zhangke has produced an ensemble of realist films with an impressive personal and authentic appeal. This paper examines how his films are characterised by a variety of accents, images of authenticity, a quotidian ambience, and a new sense of materiality within the local-global nexus. Within a tripartite model of truth, identity, and performance, Jia’s oeuvres demonstrate the powerful performativity of different modes of realism arising out of a state of conundrum when China undergoes a transition from planned economy into wholesale marketisation and globalisation. The appeal of Jia Zhangke’s fined to documentary realism. His films serve to write up a accented cinema history of his generation: rom his first feature Xiao Wu (aka The Pickpocket , I made these films because I wanted to compensate 1997) to 24 City (2008), Jia Zhangke’s films have for what was not fulfilled. I must also emphasise that Fbeen characterised by an impressive personal and au - apart from the realist mode, there are other kinds of thentic appeal. As viewers, in about a decade’s time we have representation that can be called “visual memory”; for observed an ongoing process of the director’s negotiation example, Dali’s surrealist images in the early twentieth with realism as a mode of film representation. -

Editing and Montage in International Film and Video Theory and Technique 1St Edition Pdf

FREE EDITING AND MONTAGE IN INTERNATIONAL FILM AND VIDEO THEORY AND TECHNIQUE 1ST EDITION PDF LuГѓВs Fernando Morales Morante | 9781138244078 | | | | | Editing and Montage in International Film and Video [Book] Montagein motion pictures, the editing technique of assembling separate pieces of thematically related film and putting them together into a sequence. With montage, portions of motion pictures can be carefully built up piece by piece by the director, film editor, and visual and sound technicians, who cut and fit each part with the others. Visual montage may combine shots to tell a story chronologically or may juxtapose images to produce an impression or to illustrate an association of ideas. An example of the latter occurs in Strikeby the Russian director Sergey Eisensteinwhen the scene of workers being cut down by cavalry is followed by a shot of cattle being slaughtered. Montage may also be applied to the combination of sounds for artistic expression. Montage technique developed early in cinema, primarily through the work of the American directors Edwin S. Porter — and D. Griffith — It is, however, most commonly associated with the Russian editing techniques, particularly as introduced to American audiences through the montage sequences of Slavko Verkapich in films in the s. See also photomontage. Montage Article Additional Info. Print Cite. Facebook Twitter. Give Feedback External Websites. Let us know if you have suggestions to improve this article requires login. External Websites. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica Encyclopaedia Britannica's editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working Editing and Montage in International Film and Video Theory and Technique 1st edition that content or via study for an advanced degree Editing and Montage in International Film and Video Theory and Technique 1st edition Article History. -

How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts

American Political Science Review (2017) 111, 3, 484–501 doi:10.1017/S0003055417000144 c American Political Science Association 2017 How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument GARY KING Harvard University JENNIFER PAN Stanford University MARGARET E. ROBERTS University of California, San Diego he Chinese government has long been suspected of hiring as many as 2 million people to surrep- titiously insert huge numbers of pseudonymous and other deceptive writings into the stream of T real social media posts, as if they were the genuine opinions of ordinary people. Many academics, and most journalists and activists, claim that these so-called 50c party posts vociferously argue for the government’s side in political and policy debates. As we show, this is also true of most posts openly accused on social media of being 50c. Yet almost no systematic empirical evidence exists for this claim https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144 . or, more importantly, for the Chinese regime’s strategic objective in pursuing this activity. In the first large-scale empirical analysis of this operation, we show how to identify the secretive authors of these posts, the posts written by them, and their content. We estimate that the government fabricates and posts about 448 million social media comments a year. In contrast to prior claims, we show that the Chinese regime’s strategy is to avoid arguing with skeptics of the party and the government, and to not even discuss controversial issues. We show that the goal of this massive secretive operation is instead to distract the public and change the subject, as most of these posts involve cheerleading for China, the revolutionary history of the Communist Party, or other symbols of the regime. -

43E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle Du 26 Juin Au 5 Juillet 2015 Le Puzzle Des Cinémas Du Monde

43e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle du 26 juin au 5 juillet 2015 LE PUZZLE DES CINÉMAS DU MONDE Une fois de plus nous revient l’impossible tâche de synthétiser une édition multiforme, tant par le nombre de films présentés que par les contextes dans lesquels ils ont été conçus. Nous ne pouvons nous résoudre à en sélectionner beaucoup moins, ce n’est pas faute d’essayer, et de toutes manières, un contexte économique plutôt inquiétant nous y contraint ; mais qu’une ou plusieurs pièces essentielles viennent à manquer au puzzle mental dont nous tentons, à l’année, de joindre les pièces irrégulières, et le Festival nous paraîtrait bancal. Finalement, ce qui rassemble tous ces films, qu’ils soient encore matériels ou virtuels (50/50), c’est nous, sélectionneuses au long cours. Nous souhaitons proposer aux spectateurs un panorama généreux de la chose filmique, cohérent, harmonieux, digne, sincère, quoique, la sincérité… Ambitieux aussi car nous aimons plus que tout les cinéastes qui prennent des risques et notre devise secrète pourrait bien être : mieux vaut un bon film raté qu’un mauvais film réussi. Et enfin, il nous plaît que les films se parlent, se rencontrent, s’éclairent les uns les autres et entrent en résonance dans l’esprit du festivalier. En 2015, nous avons procédé à un rééquilibrage géographique vers l’Asie, absente depuis plusieurs éditions de la programmation. Tout d’abord, avec le grand Hou Hsiao-hsien qui en est un digne représentant puisqu’il a tourné non seulement à Taïwan, son île natale mais aussi au Japon, à Hongkong et en Chine. -

A Reconsideration of Still Life Dai Jinhua Translated by Lennet Daigle

Temporality, Nature Morte, and the Filmmaker: A Reconsideration of Still Life Dai Jinhua Translated by Lennet Daigle In the world of contemporary Chinese cinema, Jia Zhangke is, in many respects, an exception to the rule: he is a director whose films almost without fail depict the lower classes or, the majority of society; a director who has continually, from the start, been dedicated to making art films; a director who has fulfilled his social responsibilities as an artist while developing an original mode of artistic expression; a director who has made the transition from independent underground films to commercial mainstream films without losing his vitality, and without suffering exclusion from western film festivals; a director famous for his autobiographical narratives who has finally “grown up”, and who has successfully drawn on his experiences to explore broader social issues. As long as China’s fifth generation filmmakers continue to make commercial compromises, and the sixth generation remains stuck – have grown but not matured in terms of style and modes of expression – Jia Zhangke will remain an exception, or even “one of a kind.” Actually, after the period in which Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth and Zhang Yimou’s films had become synonymous with the moniker “Chinese cinema” and after Zhang Yuan’s nomination of “underground cinema” to refer to what Europeans think of as “Chinese cinema” – both post-Cold War but still Cold War-style designations, the release of Platform and the inverted portrait of Mao on the film poster unexpectedly heralded the arrival of the “Jia Zhangke era” of Chinese cinema in the new millenium’s international film world, as represented primarily by European film festivals and American film studies classes. -

Channel U

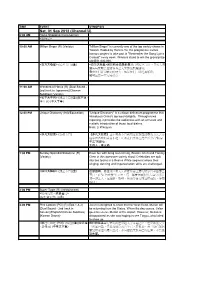

TIME EVENT SYNOPSIS Sat, 01 Sep 2012 (Channel U) 6:00 AM Home Shopping (Commercial) <购物乐> 10:00 AM Million Singer (R) (Variety) "Million Singer" is currently one of the top variety shows in Taiwan. Hosted by Harlem Yu, the programme invites famous singers to take part in "Remember the Song Lyrics Contest" every week. Winners stand to win the grand prize of NT$1,000,000. <百万大歌星> (综艺节目)(重) <百万大歌星>是目前台湾最新最热门的综艺节目。主持人庾 澄庆每期都会邀请许多艺人来参加歌唱游戏, 考验他们背记歌词的功力。如果他们一路过关斩将, 就可赢取一百万元奖金。 11:30 AM Wonders of Horus (R) (Dual Sound - 2nd track in Japanese)(Chinese Subtitles) (Variety) <科学大不同> (综艺节目)(重)(双声道 - 华日语) (中文字幕) 12:00 PM Unique Discovery (Info/Education) "Unique Discovery" is a unique delicacies programme that introduces China's top local delights. Through news reporting, it provides the audiences with an accurate and realistic introduction of these local dishes. Host: Li Wenjuan <非凡大探索> (资讯节目) 《非凡大探索》这个美食节目利用近似新闻报导的方式去介 绍中国各地的美食小吃,让观众们亲身品尝之后少有"报导 不实"的感觉。 主持人:李文娟 1:00 PM Sunday Splendid Showtime (R) Have fun with Zeng Guo Cheng, Blackie Chen and Tammy (Variety) Chen in this awesome variety show! Celebrities are split into two teams in a Red vs White segment where their singing, dancing and impersonation skills are challenged. <周日大精彩> (综艺节目)(重) 由曾国城、陈建州(黑人)和陈怡蓉主持的娱乐性丰富综艺 节目。在"红白大赏"单元里,每一集曾国城和黑人会分别带 领一班艺人,在舞蹈、歌唱、模仿等各方面互相竞技,争取 胜利。 2:00 PM Super Taste (R) (Infotainment) <时尚玩家 - 就要酱玩> (娱乐资讯节目)(重) 3:00 PM Pink Lipstick (PG) (R) (Eps 1 & 2) Jia'en is delighted to know that her best friend, Meilan will (Dual Sound - 2nd track in be returning from the States. When the day comes, Jia'en Korean)(English/Chinese Subtitles) goes to receive Meilan at the airport. -

The Reality of Illusion

Acta Univ. Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, 1 (2009) 722 The Reality of Illusion A Transcendental Reevaluation of the Problem of Cinematic Reality Melinda Szalóky Department of Film and Media Studies, University of California (Santa Barbara, USA) email: [email protected] Abstract. The paper readdresses the parallel considerations of cinema as both access to an essential, true, objective reality and as a device of deception reproducing the fallacies of a biased and reductive human perception. The claim is that the critical consideration of cinematic mediation in these ambiguous terms stems from the traditional association of cinema with the working of mental mechanisms whose logic, it is argued, follows neatly Kant's transcendental constructivist dualist model of reason and its reality. Kant's idea that our sensible but merely phenomenal experience is produced and projected by our supersensible, transcendental synthetic activity, which `in itself' is as unrecoverable as is the world that it moulds, describes perfectly the imaginary-symbolic regime of cinematic signication, whose dual nature has been considered both as a hindrance and as a guarantee of objectivity. Throughout the paper, repeated emphasis is given to the signicance of Kant's insistence to preserve, and to make palpable through the aesthetic, a noumenal unknown, a pure and never fully assessable objectivity within an increasingly self-referential, self-serving and self-enclosed human reason. It has been this modicum of a humanly inaccessible, yet arguably intuitable `excess,' the pursuit and the promise of modern art, which an aesthetically biased lm theory and practice have sought to foreground. Joining forces with Deleuze, Lyotard, and iºek, as well as with Cocteau, Tarkovsky, Wenders, and Kie±lowski, the paper promotes the necessity of continued belief in a non-human metaphysical dimension, an outside within thought that forever eludes capture. -

The Social Construction of a Myth: an Interpretation of Guo Jingming's Parable

ORIENTAL ARCHIVE 78, 2010 • 397 The Social Construction of a Myth: An Interpretation of Guo Jingming’s Parable Marco Fumian Myth and Culture Industry The nexus between mass culture production and the creation of myths is one that has very often been underlined by contemporary critics. Edgar Morin, in his early analysis of the culture industry (namely, the complex of commercial institutions producing mass culture in modern capitalist societies), observed how mass culture contributes to the shaping of the imaginary of the people “according to mental relations of projection and identification polarized on symbols, myths and images of culture as well as on the mythic or real personalities who embody those values.”1 Umberto Eco, treating the Superman comic strip cycle as a myth, analogized the popular American superhero with other heroes of classic and modern mythology. In addition, moving from a comparison between the patterns of production of religious culture in medieval Europe and the mechanisms of cultural production established by the modern American culture industry, he noted that the process of myth creation (“mythicization”) is first and foremost an institutional fact that proceeds from the top down; nevertheless, in order to become actualized, this process must sink its roots into a social body and encounter some mythopoetic tendencies emanating from the bottom that constitute the basis of a common popular sensibility.2 In the same essay, Eco also provided an apt definition of the concept of “mythicization,” which according to him would be: “an unconscious symbolization, an identification of the object with a sum of purposes that cannot be always rationalized, a projection in an image of tendencies, aspirations, fears particularly emerging in an individual, a community, a specific historical age.”3 When Guo Jingming 郭敬明 published his first novel, in 2003, a powerful aggregate of symbolic signification was generated in China, originating both from the messages transmitted by the novel and the qualities embodied by the author. -

Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics Interpersonal Meaning

OPEN ACCESS Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics ISSN 2209-0959 https://journals.castledown-puBlishers.com/ajal/ Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1 (1), 3-19 (2018) https://dx.doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v1n1.4 Interpersonal Meaning of Code-switching: An Analysis of Three TV Series WANG HUABIN a a Department of English, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] Abstract As one of the most widespread linguistic phenomena, code-switching has attracted increasing attention nowadays. Inspired by previous studies in this field, this paper addresses code-switching under the guidance of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), with the primary goal of analysing the interpersonal meanings of code-switching in three TV series. The research data were collected as follows: first, internet resources were examined to find three popular TV series with code-switching, namely I Not Stupid, Moonlight Resonance and Humble Abode; second, the data were selected, classified and observed for analysis. As the focus of this paper is interpersonal meaning, functional theories were elaborated towards a single framework for interpersonal meanings of code-switching in two parts: appraisal theory and tenor in register. The first part aims to evaluate emotions which are embedded in code-switching. The second part deals with the roles and relationships between different participants. With these theories included in the research, qualitative analyses were conducted: first of all, sample data were categorised based on their grammatical structures; then interpersonal meanings of code-switching are discussed under the guidance of these functional theories to test the applicability of SFL in this field. -

Journal of Asian Studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition

the iafor journal of asian studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: Seiko Yasumoto ISSN: 2187-6037 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Editor: Seiko Yasumoto, University of Sydney, Australia Associate Editor: Jason Bainbridge, Swinburne University, Australia Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-6037 Online: joas.iafor.org Cover image: Flickr Creative Commons/Guy Gorek The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue I – Spring 2016 Edited by Seiko Yasumoto Table of Contents Notes on contributors 1 Welcome and Introduction 4 From Recording to Ritual: Weimar Villa and 24 City 10 Dr. Jinhee Choi Contested identities: exploring the cultural, historical and 25 political complexities of the ‘three Chinas’ Dr. Qiao Li & Prof. Ros Jennings Sounds, Swords and Forests: An Exploration into the Representations 41 of Music and Martial Arts in Contemporary Kung Fu Films Brent Keogh Sentimentalism in Under the Hawthorn Tree 53 Jing Meng Changes Manifest: Time, Memory, and a Changing Hong Kong 65 Emma Tipson The Taste of Ice Kacang: Xiaoqingxin Film as the Possible 74 Prospect of Taiwan Popular Cinema Panpan Yang Subtitling Chinese Humour: the English Version of A Woman, a 85 Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) Yilei Yuan The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributers Dr. -

Post-Cinematic Affect

Post-Cinematic Affect Steven Shaviro 0 BOO KS Winchester, UK Washington, USA r First published by 0-Books, 2010 O Books ls an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., The Bothy, Deershot Lodge, Park Lane, Ropley, CONTENTS Hants, S024 OBE, UK [email protected] www.o-books.com For distributor details and how to order please visit the 'Ordering' section on oUr website. Text copyright Steven Shaviro 2009 Preface vii ISBN: 978 1 84694 431 4 1 Introduction All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of 1 this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from 2 Corporate Cannibal the publishers. 11 3 Boarding Gate The rights of Steven Shaviro as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, 35 1988. 4 Designs and Patents Act Southland Tales 64 5 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Gamer 93 6 Coda Design: Stuart Davies 131 Printed In the UK by CPI Antony Rowe Works Cited 140 Endnotes 153 We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of its business, from its global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution. Preface This book is an expanded version of an essay that originally appeared in the online journal Film-Philosophy. Earlier versions of portions of this book were delivered as talks sponsored by the Affective Publics Reading Group at the University of Chicago, by the film and media departments at Goldsmiths College, Anglia Ruskin University, University of the West of England, and Salford University, by the "Emerging Encounters in Film Theory" conference at Kings College, by the Experience Music Project Pop Conference, by the Nordic Summer University, by the Reality Hackers lecture series at Trinity University, San Antonio, and by the War and Media Symposium and the Humanities Center at Wayne State University.