Abdul Rauf EXTERNAL and INTERNAL IMPULSES of BRITISH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer of Power and the Crisis of Dalit Politics in India, 1945–47

Modern Asian Studies 34, 4 (2000), pp. 893–942. 2000 Cambridge University Press Printed in the United Kingdom Transfer of Power and the Crisis of Dalit Politics in India, 1945–47 SEKHAR BANDYOPADHYAY Victoria University of Wellington Introduction Ever since its beginning, organized dalit politics under the leadership of Dr B. R. Ambedkar had been consistently moving away from the Indian National Congress and the Gandhian politics of integration. It was drifting towards an assertion of separate political identity of its own, which in the end was enshrined formally in the new constitu- tion of the All India Scheduled Caste Federation, established in 1942. A textual discursive representation of this sense of alienation may be found in Ambedkar’s book, What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables, published in 1945. Yet, within two years, in July 1947, we find Ambedkar accepting Congress nomination for a seat in the Constituent Assembly. A few months later he was inducted into the first Nehru Cabinet of free India, ostensibly on the basis of a recommendation from Gandhi himself. In January 1950, speaking at a general public meeting in Bombay, organized by the All India Scheduled Castes Federation, he advised the dalits to co- operate with the Congress and to think of their country first, before considering their sectarian interests. But then within a few months again, this alliance broke down over his differences with Congress stalwarts, who, among other things, refused to support him on the Hindu Code Bill. He resigned from the Cabinet in 1951 and in the subsequent general election in 1952, he was defeated in the Bombay parliamentary constituency by a political nonentity, whose only advantage was that he contested on a Congress ticket.1 Ambedkar’s chief election agent, Kamalakant Chitre described this electoral debacle as nothing but a ‘crisis’.2 1 For details, see M. -

UNIT 20 PRELUDE to QUIT INDIA* Prelude to Quit India

UNIT 20 PRELUDE TO QUIT INDIA* Prelude to Quit India Structure 20.1 Introduction 20.2 Political Situation in India 1930-39 – A Background 20.3 British Imperial Strategy in India 20.4 Resignation of Ministries 20.5 Individual Satyagraha 20.6 Cripps Mission 20.7 Summary 20.8 Exercises 20.1 INTRODUCTION At the very outset of the World War II in September 1939, it became evident that India would be in the forefront of the liberation struggle by the subject countries. In fact, support to Britain in its war efforts rested on the assurance by the former that India would be freed from British subjection after the war. Imperial strategy as it was shaped in Britain was still stiff and rigid. Winston Churchill who succeeded Neville Chamberlain as the Prime Minister of Britain on 10 May 1940, declared that the aim of the war was, “victory, victory at all costs… for without victory, there is no survival… no survival for the British Empire…”. (Madhushree Mukerjee, 2010, p.3.) More than ever before, the mainstream political parties of India had to make their moves on the basis of both national politics and international developments. It is in this context that the Quit India Movement of 1942 heralded one of the most tumultuous phases in the history of the Indian national movement. The developments leading up to it were also momentous because of their long term ramification. In the course of this Unit, we will establish the pulls and pressures working on mainstream Indian politics and their regional manifestations prior to the beginning of the Quit India Movement of 1942. -

Leo Amery at the India Office, 1940 – 1945

AN IMPERIALIST AT BAY: LEO AMERY AT THE INDIA OFFICE, 1940 – 1945 David Whittington A thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education August 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii GLOSSARY iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTERS I LITERATURE REVIEW 10 II AMERY’S VIEW OF ATTEMPTS AT INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL 45 REFORM III AMERY FROM THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT OF 1935 75 UNTIL THE AUGUST OFFER OF 1940 IV FROM SATYAGRAHA TO THE ATLANTIC CHARTER 113 V THE CRIPPS MISSION 155 VI ‘QUIT INDIA’, GANDHI’S FAST AND SOCIAL REFORM 205 IN INDIA VII A SUCCESSOR TO LINLITHGOW, THE STERLING BALANCES 253 AND THE FOOD SHORTAGES VIII FINAL ATTEMPTS AT CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM BEFORE THE 302 LABOUR ELECTION VICTORY CONCLUSION 349 APPENDICES 362 LIST OF SOURCES CONSULTED 370 ABSTRACT Pressure for Indian independence had been building up throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, initially through the efforts of the Indian National Congress, but also later, when matters were complicated by an increasingly vocal Muslim League. When, in May 1940, Leo Amery was appointed by Winston Churchill as Secretary of State for India, an already difficult assignment had been made more challenging by the demands of war. This thesis evaluates the extent to which Amery’s ultimate failure to move India towards self-government was due to factors beyond his control, or derived from his personal shortcomings and errors of judgment. Although there has to be some analysis of politics in wartime India, the study is primarily of Amery’s attempts at managing an increasingly insurgent dependency, entirely from his metropolitan base. -

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 18 6 (paperback edition) ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) I never had the advantage of a university education. Winston Churchill, speech on accepting an honorary degree at the University of Copenhagen, 10 October 1950 The privilege of a university education is a great one; the more widely it is extended the better for any country. Winston Churchill, Foundation Day Speech, University of London, 18 November 1948 I always enjoy coming to Bristol and performing my part in this ceremony, so dignified and so solemn, and yet so inspiring and reverent. Winston Churchill, Chancellor’s address, University of Bristol, 26 November 1954 Contents Preface ix List of abbreviations xi List of illustrations xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Freedom Struggle After the Civil Disobedience Movement

Freedom Struggle after the Civil Disobedience Movement Political Context: Following the withdrawal of the Civil Disobedience Movement, there was a two-stage debate on the future strategy of the nationalists: the first stage was on what course the national movement should take in the immediate future, i.e., during the phase of non-mass struggle (1934-35); and the second stage, in 1937, considered the question of office acceptance in the context of provincial elections held under the autonomy provisions of the Government of India Act, 1935. First Stage Debate on 1. Constructive work on Gandhian lines. 2. Constitutional struggle and participation in elections. 3. Rejection of constructive work and constitutional struggle— continuation of CDM. Government of India Act, 1935 Amidst the struggle of 1932, the Third RTC was held in November, again without Congress participation. The discussions led to the formulation of the Act of 1935. Main Features 1. An All India Federation It was to comprise all British Indian provinces, all chief commissioner’s provinces and the princely states. The federation’s formation was conditional on the fulfilment of (i) states with allotment of 52 seats in the proposed Council of States should agree to join the federation, and (ii) aggregate population of states in the above category should be 50 per cent of the total population of all Indian states. Since these conditions were not fulfilled, the proposed federation never came up. The central government carried on Up to 1946 as per the provisions of Government of India Act, 1919. 2. Federal Level: Executive a. The governor-general was the pivot of the entire Constitution. -

Major Gwilym Lloyd-George As Minister of Fuel and Power, 1942–1945

131 Major Gwilym Lloyd-George As Minister Of Fuel And Power, 1942 –1945 J. Graham Jones Among the papers of A. J. Sylvester (1889–1989), Principal Private Secretary to David Lloyd George from 1923 until 1945, purchased by the National Library of Wales in 1990, are two documents of considerable interest, both dating from December 1943, relating to Major Gwilym Lloyd-George, the independent Liberal Member for the Pembrokeshire constituency and the second son of David and Dame Margaret Lloyd George. At the time, Gwilym Lloyd-George was serving as the generally highly-regarded Minister for Fuel and Power in the wartime coalition government led by Winston Churchill. The first is a letter, probably written by David Serpell, who then held the position of private secretary to Lloyd-George at the Ministry of Fuel and Power (and who was a warm admirer of him), to A. J. Sylvester.1 It reads as follows: PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL 4 December, 1943 Dear A. J., I am afraid I did not get much time for thought yesterday, but I have now been able to give some time to the character study you spoke to me about … The outstanding thing in [Gwilym] Ll.G’s character seems to me to be that he is genuinely humane – i.e. he generally has a clear picture in his mind of the effects of his policies on the individual. In the end, this characteristic will always over-shadow others when he is determining policy. To some extent, it causes difficulty as he looks at a subject, not merely as a Minister of Fuel and Power, but as a Minister of the Crown, and thus sees another Minister’s point of view more readily perhaps than that Minister will see his. -

On the Basis of the Framework Provided by the Cabinet Mission, a Constituent Assembly the Assembly Had 398 Members out of Which 292 Members Were Elected Through

On the basis of the framework provided by the Cabinet Mission, a Constituent Assembly The assembly had 398 members out of which 292 members were elected through was constituted on 9th December, 1946. provincial assembly elections. The Constituent Assembly of India was elected to write the Constitute of India. 93 were members representing the Indian Princely states and 4 members The first meeting of the Constituent Assembly took place on December 9, 1946 at represented the Chief Commissioners’ Provinces. New Delhi with Dr Sachidanand being elected as the interim President of the Assembly. The strength of the committee later reduced to 299 due to the India- Pakistan However, on December 11, 1946, Dr. Rajendra Prasad was elected as the President and partition under the Mountbatten Plan of 3rd August 1947, and a separate H.C. Mukherjee as the Vice-President of the Constituent Assembly. constituent assembly was set up for them. Thus the membership of the Its last session was held on 24 January 1950. X committee was reduced to 299 members. Composition of Constituent Assembly Introduction Constituent Assembly of India Demand for constitutional assembly It was in 1934 that the idea of a Constituent Assembly for India was put forward for the first time by M.N. Roy, a pioneer of communist movement in India. In 1935, the Indian National Congress (INC), for the first time, officially demanded a Constituent Assembly to frame the Constitution of India. In 1938, Jawaharlal Nehru, on behalf the INC declared that ‘the Constitution of free India must be framed, without outside interference, by a Constituent Assembly elected on the basis of adult franchise’. -

Class:-8Th History, Chapter:-11 A. Fill in the Blanks:- 1. in 1931, Japan

Class:-8th History, Chapter:-11 A. Fill in the blanks:- 1. In 1931, Japan, which had become a powerful imperialist country, invaded China. 2. Gandhiji, in his speech, gave the mantra 'Do or Die' during the Quit India movement. 3. When the Cripps Mission failed, the Quit India movement started in 1942. 4. Subhash Chandra Bose formed a new party could the Forward Bloc. 5. The Muslim League propagated the two-nation theory. B. Match the following:- 1. Cripps Mission d. Stafford Cripps 2. Quit India Movement c. Mahatma Gandhi 3. Azad Hind Fauj e. Subhash Chandra Bose 4. Independence of India b. 1947 5. Indian Constitution a. 1950 C. Write (T) for true and (F) for false. 1. After the failure of the INA, Japan captured Indian. (False) 2. The Congress declared that Imperialism and Fascism were essential for peace and progress. (False) 3. During the 1942 Movement, parallel governments were formed in different parts of India. (False) 4. INA was also known as the 'Rani Jhansi Regiment'. (False) 5. Lord Mountbatten was against the formation of two nations-India and Pakistan. (False) D. Write short notes on the following topics:- 1. Quit India Movement :- The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All-India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 9 August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule in India. Gandhi Ji gave the mantra- 'Do or Die'. 2. formation of the INA :- Azad Hind Fauj (INA), led by Subhash Chandra Bose in cooperation with the Japanese army, waged a grim fight as the Quit India Movement failed. -

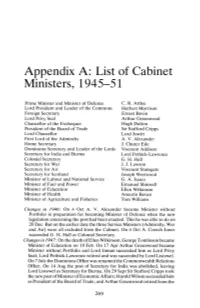

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

Progressive Consensus.Qxd

The Progressive Consensus in Perspective Iain McLean and Guy Lodge FEBRUARY 2007 © ippr 2007 Institute for Public Policy Research www.ippr.org The Institute for Public Policy Research (ippr) is the UK’s leading progressive think tank and was established in 1988. Its role is to bridge the political divide between the social democratic and liberal traditions, the intellectual divide between academia and the policy making establishment and the cultural divide between government and civil society. It is first and foremost a research institute, aiming to provide innovative and credible policy solutions. Its work, the questions its research poses, and the methods it uses are driven by the belief that the journey to a good society is one that places social justice, democratic participation, economic and environmental sustainability at its core. This paper was first published in February 2007. © ippr 2007 30-32 Southampton Street, London WC2E 7RA Tel: 020 7470 6100 Fax: 020 7470 6111 www.ippr.org Registered Charity No. 800065 About the authors Iain McLean is Professor of Politics and Director of the Public Policy Unit, Oxford University. He has published widely in political science and 20th-century British history, including Rational Choice and British Politics (OUP, 2001) and, with Jennifer Nou, ‘Why should we be beggars with the ballot in our hand? Veto players and the failure of land value taxation in the UK, 1909-14’, British Journal of Political Science, 2006. Guy Lodge is a Research Fellow in the democracy team at ippr. He specialises in governance and constitutional reform and has published widely in this area. -

Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945

Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 By Roger Spalding Narratives of Delusion in the Political Practice of the Labour Left 1931–1945 By Roger Spalding This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Roger Spalding All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0552-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0552-0 For Susan and Max CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ............................................................................................... 14 The Bankers’ Ramp Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 40 Fascism, War, Unity! Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 63 From the Workers to “the People”: The Left and the Popular Front Chapter -

Download Flyer

ANTHEM PRESS INFORMATION SHEET Azad Hind Subhas Chandra Bose, Writing and Speeches 1941-1943 Edited by Sisir K. Bose and Sugata Bose Pub Date: October 2004 Category: HISTORY / Asia / General Binding: Paperback BISAC code: HIS003000 Price: £14.95 / $32.95 BIC code: HBJF ISBN: 978184330839 Extent: 200 pages Rights Held: World Size: 234 x 156mm / 9.2 x 6.1 Description A collection of Subhas Chandra Bose’s writings and speeches, 1941–1943. This volume of Netaji Bose’s collected works covers perhaps the most difficult, daring and controversial phase in the life of India’s foremost anti-colonial revolutionary. His writings and broadcasts of this period cover a broad range of topics, including: the nature and course of World War Two; the need to distinguish between India’s internal and external policy in the context of the international war crisis; plans for a final armed assault against British rule in India; dismay at, and criticism of, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union; the hypocrisy of Anglo- American notions of freedom and democracy; the role of Japan in East and South East Asia; the reasons for rejecting the Cripps offer of 1942; support for Mahatma Gandhi and the Quit India movement later that year and reflections on the future problems of reconstruction in free India. Readership: For students and scholars of Indian history and politics. Contents List of Illustrations; Dr Sisir Kumar Boses and Netaji's Work; Acknowledgements; Introduction, Writings and Speeches; 1. A Post-Dated Letter; 2. Forward Bloc: Ist Justifications; 3. Plan of Indian Revolution; 4. Secret Memorandum to the German Governemtn; 5.