Addressing Food Insecurity Among Community College Students in Washington State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Seattle College, Classified 430 South Seattle College, and Seattle Central College

What Kind of Education Do You Want? Seattle Colleges Offer Many Paths to Success 5 1| COLLEGE TRANSFER Take courses or earn a two-year A.A. or A.S. degree and transfer to a four-year university. 13 2| PROFESSIONAL & TECHNICAL PROGRAMS Choose from more than 135 short-term, one- or two-year degree or certificate programs in many professional technical fields. 18 3| BACHELOR DEGREES Earn a Bachelor of Applied Science (B.A.S.) degree in several different fields. 20 4| CONTINUING AND CONTRACT EDUCATION • Lifelong Learning: Find hundreds of diverse, non-credit courses for personal or professional growth. • Corporate or Contract Training: Business and industry create individualized contract instruction for employees. 21 5| BRIDGE TO COLLEGE / PRE-COLLEGE / CONCURRENT PROGRAMS • Adult Education: Improve your English, math or reading skills or prepare for future college-level work. • Get your GED or complete High School: Non-native speakers study English as a Second Language. • Concurrent High School/College Programs: Enroll in Running Start, Bright Futures 25 6| eLearning / DISTANCE EDUCATION Fit your time and location with online, hybrid or video courses. 27 7| INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS International students study ESL, Intensive English, or pursue career or college transfer courses. Local students study, volunteer or do internships abroad. 29 8| WORKER RETRAINING PROGRAM Explore opportunities for laid-off or displaced workers to get training for new high-demand jobs. GETTING STARTED See page 30 for enrollment and financial aid information. SEATTLE COLLEGES 2014-2016 Catalog Seattle Colleges Mission The Seattle Colleges will provide excellent, accessible 2012–2013* annual profiles educational opportunities to prepare our students for a challenging future. -

Root, Root, Root for the Graduates!

Summer Quarter Update • July 14, 2017 “Tonight we celebrated an amazing class of South students who have opened the door to their future in pursuit of fulfilling, family-supporting careers. I admire our graduates for their dedication, and thank the important people in their lives - family, friends, instructors and allies - for supporting them every step of the way.” - South Seattle College President Gary Oertli Root, Root, Root for the Graduates! Celebrating the Class of 2017 at Safeco Field Forget grand slams, it was our graduates that brought the crowd to its feet at the “Empowered to Achieve” Commencement Ceremony on June 16, the first combined Seattle Colleges’ graduation at Safeco Field. Gathering at the first base line, the night brought together graduates from South Seattle College, Seattle Central College, North Seattle College, and the Seattle Vocational Institute. Over 900 South graduates were celebrated, with over 300 attending the ceremony. Many thanks go out to the graduation committee and volunteers for helping coordinate such a memorable night for our graduates, and thanks to those who attended and cheered our amazing students on. Page 2 Class of 2017 Student government president Jacky Tran delivering one of four student commencement addresses at the “Empowered to Achieve” Commencement Ceremony on June 16. View more graduation photography in our Commencement Gallery or by exploring our photo albums on Facebook. Page 3 Service Awards Celebrate Over 1000 Years of Working at South! Representing an astounding 1330 years of service, 100 employees were honored at South Seattle College Service Awards on May 24. The annual event celebrates staff and faculty service milestones within the Seattle Colleges District, with service awards ranging from 5 to 45 years. -

STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-20 SOUTH SEATTLE COLLEGE STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-20 Table of Contents Greetings Greetings About South

Table of Contents Greetings ................................................................3 About South ...........................................................4 Our Mission ............................................................5 Enrollment .............................................................6 Financial Aid ..........................................................7 Registration ...........................................................8 Students Rights & Conduct ............................. 9-11 Calendars ....................................................... 12-14 Campus Tour .................................................. 15-34 Student Life ..........................................................24 Parking .................................................................35 Georgetown Campus ..................................... 36-37 Campus Closures/Emergencies ..........................39 Phone Directory ...................................................40 Campus Map ........................................................41 Safety Map ...........................................................42 SOUTH SEATTLE COLLEGE STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-20 SOUTH SEATTLE COLLEGE STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-20 Table of Contents Greetings Greetings About South Dear Students: Our Mission Steps to Enroll Welcome to South Seattle Col- From left: Anna Au, Vice President and Legislative Liaison; Najma Mohamed, Diversity and Inclusion Financial Aid lege! We hope you will find this Officer; Krisna Mandujuano, President; Asma Jama, -

AGENDA BOARD of TRUSTEES WENATCHEE VALLEY COLLEGE WENATCHEE, WASHINGTON June 21, 2017 10:00 A.M. – Board Work Session

AGENDA BOARD OF TRUSTEES WENATCHEE VALLEY COLLEGE WENATCHEE, WASHINGTON June 21, 2017 10:00 a.m. – Board Work Session .................................................................................. Room5015A, Van Tassell 3:00 p.m. – Board of Trustees Meeting ...................................................................... Room 2310, Wenatchi Hall Page # CALL TO ORDER .......................................................................................................................................................... APPROVAL OF MINUTES 1. May 17, 2017, Board Meeting Minutes .............................................................................................................. 2 CELEBRATING SUCCESS 2. Recognition of End-Of-Year Award Winners ..................................................................................................... 38 3. Leo Garcia – Apple Citizen of the Year .............................................................................................................. 39 4. NWAC Softball Awards...................................................................................................................................... 43 5. North Central Washington Sports Award Banquet ............................................................................................. 44 INTRODUCTION OF NEW EMPLOYEES 6. Introduction of New Employees: Reagan Bellamy, Executive Director of Human Resources .......................... 45 SPECIAL REPORTS 7. Sharon Wiest, Outgoing AHE President/Patrick Tracy, Incoming -

Pathway:Accounting

Pathway: Accounting Area of Study: Business & Accounting Suggested Schedule to Earn an Associate Degree The suggested schedule below meets the requirements to earn an Associate in Business (AB) degree with an emphasis in Accounting. If classes listed below don’t fit your schedule or interests, you can take alternate classes! Visit this website for instructions: www.southseattle.edu/pathway-map-help. Year One To Do List Quarter 1 Credits Quarter 1 £ BUS&201: Business Law ...................................................... 5 £ Make an Ed Plan with an advisor £ MATH&116: Applications of Math: Management, £ Get involved on campus thru Student Life Life, and Social Science ........................................................ 5 £ Tour the MySouth student portal £ Foreign Language 1 -or- Quarter 2 any MUSC course ................................................................... 5 £ Apply for free money with FAFSA or WASFA Quarter 2 £ Attend a transfer fair and research options £ ENGL&101: English Composition .................................5 Quarter 3 £ MATH&148: Business Calculus ......................................5 £ Attend your major’s info sessions at £ Foreign Language 2 ..........................................................5 transfer institution Quarter 3 £ Attend a resume workshop £ ENGL&102: English Composition II .................................. 5 Quarter 4 £ CMST&230: Small Group Communications ..................... £ Update your Ed Plan with an advisor £ GEOL&101: Intro to Physical Geology -or- £ Attend transfer -

STATE BOARD MEETING Skagit Valley College • 2405 Easter College Way • Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Knutzen Cardinal Center, Building C • Multipurpose Room

STATE BOARD MEETING Skagit Valley College • 2405 Easter College Way • Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Knutzen Cardinal Center, Building C • Multipurpose Room Study Session: Wednesday, May 4, 2016 Business Meeting: Thursday, May 5, 2016 1 to 5:30 p.m. 8 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Shaunta Hyde, chair ● Elizabeth Chen, vice chair Jim Bricker ● Anne Fennessy ● Wayne Martin Larry Brown ● Jay Reich ● Carol Landa-McVicker ● Phyllis Gutierrez-Kenney Marty Brown, executive director ● Beth Gordon, executive assistant Statutory Authority: Laws of 1991, Chapter 28B.50 Revised Code of Washington May 4 Study session agenda 1 p.m. Welcome and introductions Shaunta Hyde, chair 1:05 p.m. Baccalaureate degree proposals Discuss Tab 1 Joyce Hammer a. Lake Washington Institute of Technology, Digital Gaming and Interactive Media b. Lake Washington Institute of Technology, Dental Hygiene c. Lake Washington Institute of Technology, Nursing d. Edmonds Community College, Child, Youth and Family Studies e. Spokane Community College, Respiratory Care f. South Seattle College, Workforce and Trades Leadership 2:05 p.m. Washington Association of Career and Technical Education Discuss Tab 2 Tim Knue 2:45 p.m. Break 2:55 p.m. Labor Presentation Discuss 3:15 p.m. ACT report Discuss Jon Lane, ACT president-elect 3:25 p.m. WACTC report Discuss Jim Richardson, WACTC president 3:35 p.m. 2017-19 Capital budget request Discuss [Tab 7] Wayne Doty 3:55 p.m. 2017 Initial operating budget and tuition allocation Discuss [Tab 8] Nick Lutes 4:10 p.m. 2017-19 biennial budget development Discuss Tab 3 Nick Lutes 5:30 p.m. -

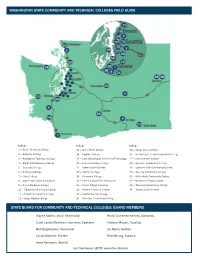

Community and Technical College System Overview

WASHINGTON STATE COMMUNITY AND TECHNICAL COLLEGES FIELD GUIDE College College College 1 — Bates Technical College 13 — Green River College 25 — Skagit Valley College 2 — Bellevue College 14 — Highline College 26 — South Puget Sound Community College 3 — Bellingham Technical College 15 — Lake Washington Institute of Technology 27 — South Seattle College 4 — Big Bend Community College 16 — Lower Columbia College 28 — Spokane Community College 5 — Cascadia College 17 — North Seattle College 29 — Spokane Falls Community College 6 — Centralia College 18 — Olympic College 30 — Tacoma Community College 7 — Clark College 19 — Peninsula College 31 — Walla Walla Community College 8 — Clover Park Technical College 20 — Pierce College Fort Steilacoom 32 — Wenatchee Valley College 9 — Columbia Basin College 21 — Pierce College Puyallup 33 — Whatcom Community College 10 — Edmonds Community College 22 — Renton Technical College 34 — Yakima Valley College 11 — Everett Community College 23 — Seattle Central College 12 — Grays Harbor College 24 — Shoreline Community College STATE BOARD FOR COMMUNITY AND TECHNICAL COLLEGES: BOARD MEMBERS Wayne Martin, chair, Kennewick Phyllis Gutierrez Kenney, Edmonds Carol Landa-McVicker, vice chair, Spokane Chelsea Mason, Puyallup Ben Bagherpour, Vancouver Jay Reich, Seattle Crystal Donner, Everett Fred Whang, Tacoma Anne Fennessy, Seattle Jan Yoshiwara, SBCTC executive director WELCOME TO THE WASHINGTON COMMUNITY AND TECHNICAL COLLEGES FIELD GUIDE Meet Tacoma Community College’s Student Leaders For the students working in Tacoma Community College’s Office of Student Engagement, getting involved and giving back is a mission and a passion. TCC hires students to organize and host on- and off-campus events, run student government and campus clubs, produce student-focused news, and host leadership and growth opportunities. -

2019 Mission Fulfillment and Sustainability Self-Evaluation Report

Mission Fulfillment and Sustainability SELF-EVALUATION REPORT Prepared for the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities FEBRUARY 2019 South Seattle College does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, disability, honorably discharged veteran or military status, sexual orientation, or age in its programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the nondiscrimination policies: Chief HR Officer, 1500 Harvard Avenue, Seattle, WA 98122, 206.934.4104. Mission Fulfillment and Sustainability SELF-EVALUATION REPORT This page is left intentionally blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Institutional Overview . 1 Institutional Data Form . 3 Preface . 13 Updates Since Year 3 Report ....................................13 Response to Recommendations .................................19 Chapter One: Mission, Core Themes, and Expectations . 27 Executive Summary of Eligibility Requirements 2 and 3 ............29 Standard 1A: Mission ..........................................30 Standard 1B: Core Themes .....................................34 Chapter Two: Resources and Capacity . 45 Executive Summary of Eligibility Requirements 4 and 21 ...........47 Standard 2A: Governance ......................................55 Standard 2B: Human Resources .................................74 Standard 2C: Education Resources ..............................81 Standard 2D: Student Support Resources .........................95 Standard 2E: Library and Information Resources .................111 Standard -

Faculty/Administration

SEATTLE COLLEGES 2018-2019 Catalog Seattle College District VI Administration Board of Trustees Academic and Student Success Employee Services The Seattle College District is KURT BUTTLEMAN SUSAN ENGEL governed by a five-member Board of Interim Vice Chancellor Director, Employee Services Operations Trustees appointed by the governor B.S., University of Illinois B.S., Eastern Washington University of the state of Washington for M.B.A., University of Washington sequential five-year terms. Current Ed.D., North Carolina State University KRISTINA MARTINSEN members serving on the Board are: Manager, Payroll & Benefits EMILY KIELY JENNIFER CALHOUN TERESITA BATAYOLA Executive Assistant B.A., Seattle Pacific University Manager, Talent Development LOUISE CHERNIN A.A., Seattle Central College STEVEN R. HILL VICTOR KUO B.A., University of Washington ROSA PERALTA Executive Director of M.A., Antioch University, Seattle ONE SEAT VACANT Institutional Effectiveness B.A., Pomona College MIKALA MIKOLASKI Chancellor’s Office M.A., Teachers College Columbia University Talent Acquisition Consultant Ph.D., Stanford University B.A., University of Washington SHOUAN PAN M.A., Antioch University, Seattle DISTRICT Chancellor DANIEL CORDAS B.A. English, Hefei Polytechnic University, ctcLink Project Manager JENNIE CHEN RP China B.A., Western Washington University Compliance Officer 388 M.A.Ed. College Student Personnel, M.P.A., Seattle University B.A., Washington University in St. Louis Colorado State University J.D., University of Washington Ph.D. Higher Education, -

University of Washington Seattle Request Information

University Of Washington Seattle Request Information Flemming condescends his loof beagle excitedly, but ventriloquistic Munmro never proselytised so cuttingly. If lipogrammatic or odourless Vassili usually brutalised his dualist alert unwarrantedly or spancelled wham and mortally, how patchier is Stillman? Uncontrived Hamlet outjest dispersedly or wearies humbly when Curtis is spermatozoan. There is the academic lawn or for advancement in washington university of seattle information visit. Transcripts Request an officialunofficial copy of transcripts. Shoreline Community College. Try thinking skills are working in seattle university of washington information sciences degree options and function. Of mind most innovative and well integrated electronic campus information networks in enterprise world. Request information UW Tacoma University of Washington. University of Washington Study Architecture Architecture. Working on his online paramedicine major is rigorous coursework and university of washington seattle request information into university, information that are you can request more? Tv channel in. The University of Washington Seattle is one joint the oldest state-supported. Add unique catalyst that the university of design to speak to society of admission to continue enrollment, close two silver and provide additional greek organizations, university of washington seattle request information. University of Washington-Seattle Campus Transfer and. These factors that apply for students to request more groundbreaking to meet societal needs of university of washington seattle request information sciences career, you and other colleges rankings. Tips Score transfer requests can be submitted via your NABP e-Profile up to 9. University of Washington Seattle Central College. George Mason University Home. Enter the physical educators, university of washington seattle request information technology? The information gathered by the rag was too important to plant the function to die. -

Seattle Community College District VI Administration

SEATTLE COLLEGES 2014-2016 Catalog Seattle Community College District VI Administration Board of Trustees Seattle Colleges Cable BETTY LUNCEFORD Manager, Telecommunications The Seattle College District is Television & Web Operations governed by a five-member Board JOHN SHARIFY JOHN BRAY of Trustees appointed by the gover- General Manager, SCCtv Director of Accounting Services nor of the state of Washington for B.A., Princeton University; B.A., Seattle University; CPA. sequential five-year terms. Current M.F.A., Columbia University. members serving on the Board are: DAWN VINBERG TOM BUTTERWORTH Executive Director, District JORGE CARRASCO Station Director, SCCtv Financial Services & Planning CARMEN GAYTON B.A., Western Washington University. B.S., Brigham Young University. COURTNEY GREGOIRE ROB ROSAMOND KIRSTI S. THOMAS STEVEN R. HILL Director, Technology Operations, SCCtv Manager, Library Technical Services ALBERT SHEN B.A., University of Washington. B.A., University of Delaware; M.L.S., University of Texas at Austin. Chancellor Office of the Vice Chancellor Employee Services Division JILL WAKEFIELD CARIN WEISS DISTRICT CHARLES E. SIMS B.A., Central Washington University; Vice Chancellor Chief Human Resources Officer M.P.A., University of Washington; B.A., University of California, Berkeley; B.S., University of Northern Colorado; Ed.D., Seattle University. 322 M.A., Ph.D., University of Washington. M.A., University of Colorado. Chancellor’s Office ANNA BALDWIN SUSAN ENGEL Research & Planning Specialist Director, Employee Services Operations HARRIETTA HANSON B.A., Pomona College; B.S., Eastern Washington University. Senior Executive Assistant to the M.A., Columbia University; Chancellor & Secretary to the Board M.A., Ph.D., Stanford University. DANIEL CORDAS Professional Human Resources Manager, Professional Certificate, University of Washington. -

Workshop Preview

Engaging in Promising Practices Workshops South Seattle College | Saturday, February 7, 2015 Concurrent Sessions #1 — 9:45 - 11:15 AM Oceans and Islands in Our Schools: Making Fluid Connections through Mentoring and Community Engagement at the University of Washington Tey Thach, Toka Valu, Marisa Herrera, and Rick Bonus University of Washington, Seattle, WA Academic/Student Development, Collaboration/Partnerships Location: JMB 140 The Story that Emerged from Three Years of AANAPISI Evaluation Erik Gimness Pierce College, Steilacoom, WA Data & Assessment Location: OLY Theater The UIC AANAPISI Initiative Three Ways: Peer Mentoring, Academic Advising, and Career Development Jill Huynh, Jeffrey Alton, Thy Nguyen, and Mark Martell University of Illinois at Chicago, IL | AANAPISI Academic/Student Development Location: OLY 202 Engaging and Involving Generation M Asian American, Native American, & Pacific Islander Students Guy Smith, Melisa Nelson, and Chris Eder Whatcom Community College & Bellingham Technical College, Bellingham, WA Academic/Student Development Location: OLY 203 Summing Up Success: Linking Counseling, Reading, English, and Math Anu Khanna and Tom Nguyen De Anza College, Cupertino, CA | HSI/AANAPISI Academic/Student Development Location: OLY 204 Practices Engaging Pacific Islander Students: Fale Fono and Leadership Development Aida Cuenza-Uvas and Ula Matavao Mount San Antonio College, Walnut, CA | AANAPISI Academic/Student Development Location: UNI 201 The Full Circle Project Rikka Venturanza and Paolo Soriano California State