History of Theatre Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

Storytelling and Community: Beyond the Origins of the Ancient

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN by Sarah Kellis Jennings Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Theatre Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 3, 2013 ii STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY: BEYOND THE ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT THEATRE, GREEK AND ROMAN Project Approved: T.J. Walsh, Ph.D. Department of Theatre (Supervising Professor) Harry Parker, Ph.D. Department of Theatre Kindra Santamaria, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 GREEK THEATRE .............................................................................................................1 The Dithyramb ................................................................................................................2 Grecian Tragedy .............................................................................................................4 The Greek Actor ............................................................................................................. 8 The Satyr Play ................................................................................................................9 The Greek Theatre Structure and Technical Flourishes ...............................................10 Grecian -

The Characteristics of Greek Theater

The Characteristics of Greek Theater GHS AH: Drama Greek Theater: Brief History n Theater owes much to Greek drama, which originated some 27 centuries ago in 7th century BCE. n Greeks were fascinated with the mystery of the art form. n Thespis first had the idea to add a speaking actor to performances of choral song and dance. The term Thespian (or actor) derives from his name. Greek Theater: Brief History n Greek plays were performed in outdoor theaters, usually in the center of town or on a hillside. n From the 6th century BCE to the 3rd century BCE, we see the development of elaborate theater structures. n Yet, the basic layout of the theater remained the same. Tragedy and Comedy n Both flourished in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, when they were performed, sometimes before 12,000 or more people at religious festivals in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine and the patron of the theater. n Tragedy=dealt with stories from the past n Comedy=dealt with contemporary figures and problems. Introduction to Greek Drama n Video segment: About Drama Complete the worksheet as you watch the video segment. n The masks of comedy and tragedy are emblems of theater today. and they originated in ancient Greece. What are the parts of a Greek theater? What is a Greek Chorus? n The Greek Chorus was a group of poets, singers, and/or dancers that would comment on events in the play. n 12 to 50 members would normally comprise the chorus. n They would explain events not seen by the audience (ex. -

Mapping the History of Malaysian Theatre: an Interview with Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof

ASIATIC, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2010 Mapping the History of Malaysian Theatre: An Interview with Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof Madiha Ramlan & M.A. Quayum1 International Islamic University Malaysia It seems that a rich variety of traditional theatre forms existed and perhaps continues to exist in Malaysia. Could you provide some elucidation on this? If you are looking for any kind of history or tradition of theatre in Malaysia you won’t get it, because of its relative antiquity and the lack of records. Indirect sources such as hikayat literature fail to mention anything. Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai mentions Javanese wayang kulit, and Hikayat Patani mentions various music and dance forms, most of which cannot be precisely identified, but there is no mention of theatre. The reason is clear enough. The hikayat generally focuses on events in royal court, while most traditional theatre developed as folk art, with what is known as popular theatre coming in at the end of the 19th century. There has never been any court tradition of theatre in the Malay sultanates. In approaching traditional theatre, my own way has been to first look at the proto- theatre or elementary forms before going on to the more advanced ones. This is a scheme I worked out for traditional Southeast Asian theatre. Could you elaborate on this? Almost all theatre activity in Southeast Asia fits into four categories as follows: Proto-Theatre, Puppet Theatre, Dance Theatre and Opera. In the case of the Philippines, one could identify a separate category for Christian theatre forms. Such forms don’t exist in the rest of the region. -

History of Theatre the Romans Continued Theatrical Thegreek AD (753 Roman Theatre fi Colosseum Inrome, Which Was Built Between Tradition

History of theatre Ancient Greek theatre Medieval theatre (1000BC–146BC) (900s–1500s) The Ancient Greeks created After the Romans left Britain, theatre purpose-built theatres all but died out. It was reintroduced called amphitheatres. during the 10th century in the form Amphitheatres were usually of religious dramas, plays with morals cut into a hillside, with Roman theatre and ‘mystery’ plays performed in tiered seating surrounding (753BC–AD476) churches, and later outdoors. At a the stage in a semi-circle. time when church services were Most plays were based The Romans continued the Greek theatrical tradition. Their theatres resembled Greek conducted in Latin, plays were on myths and legends, designed to teach Christian stories and often involved a amphitheatres but were built on their own foundations and often enclosed on all sides. The and messages to people who could ‘chorus’ who commented not read. on the action. Actors Colosseum in Rome, which was built between wore masks and used AD72 and AD80, is an example of a traditional grandiose gestures. The Roman theatre. Theatrical events were huge works of famous Greek spectacles and could involve acrobatics, dancing, playwrights, such as fi ghting or a person or animal being killed on Sophocles, Aristophanes stage. Roman actors wore specifi c costumes to and Euripedes, are still represent different types of familiar characters. performed today. WORDS © CHRISTINA BAKER; ILLUSTRATIONS © ROGER WARHAM 2008 PHOTOCOPIABLE 1 www.scholastic.co.uk/junioredplus DECEMBER 2008 Commedia dell’Arte Kabuki theatre (1500s Italy) (1600s –today Japan) Japanese kabuki theatre is famous This form of Italian theatre became for its elaborate costumes and popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. -

Evolution of Street Theatre As a Tool of Political Communication Sangita

Evolution of Street Theatre as a tool of Political Communication Sangita De & Priyam Basu Thakur Abstract In the post Russian Revolution age a distinct form of theatrical performance emerged as a Street Theatre. Street theatre with its political sharpness left a crucial effect among the working class people in many corner of the world with the different political circumstances. In India a paradigm shift from proscenium theatre to the theatre of the streets was initiated by the anti-fascist movement of communist party of India under the canopy of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). In North India Street theatre was flourished by Jana Natya Manch (JANAM) with the leadership of Safdar Hashmi. This paper will explore the background of street theatre in India and its role in political communication with special reference to historical and analytical study of the role of IPTA, JANAM etc. Keywords: Street Theatre, Brecht, Theatre of the Oppressed, Communist Party of India (CPI), IPTA, JANAM, Safdar Hashmi, Utpal Dutta. Introduction Scholars divided the history of theatre forms into the pre-Christian era and Christian era. Aristotle’s view about the structure of theatre was based on Greek tragedy. According to the scholar Alice Lovelace “He conceived of a theatre to carry the world view and moral values of those in power, investing their language and symbols with authority and acceptance. Leaving the masses (parties to the conflict) to take on the passive role of audience...........The people watch and through the emotions of pity & grief, suffer with him.” Bertolt Brecht expressed strong disagreement with the Aristotelian concept of catharsis. -

Raja Edepus, And: Making of “Raja Edepus.” Lynda Paul

Raja Edepus, and: Making of “Raja Edepus.” Lynda Paul Asian Music, Volume 42, Number 1, Winter/Spring 2011, pp. 141-145 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/amu/summary/v042/42.1.paul.html Access Provided by Yale University Library at 02/05/11 2:36AM GMT Recording Reviews Raja Edepus. Directed and produced by William Maranda. DVD. 92 min- utes. Vancouver BC: Villon Films, 2009. Available from http://www.villon! lms .com. Making of “Raja Edepus.” Directed and produced by William Maranda. DVD. 27 minutes. Vancouver BC: Villon Films, 2008. Available from http://www .villon! lms.com. If, at ! rst glance, ancient Greek tragedy and contemporary Balinese dance- drama seem unlikely theatrical companions, the production Raja Edepus puts any such doubts to rest. Produced by William Maranda with artistic direction by Nyoman Wenten, Raja Edepus is a compelling Balinese rendering of the ancient Sophocles drama, Oedipus Rex. Created for live performance at the Bali Arts Festival in 2006, Raja Edepus is now available to a wider public through two DVDs: one, a recording of the show, and the other, a documentary about the performance’s preparation. " e live production fuses musical and dramatic techniques used in contem- porary Balinese theater with techniques thought to have been used in ancient Greek theater. As Maranda describes on the Making of “Raja Edepus” DVD, the two types of theater—though separated by 2500 years and much of the earth— have signi! cant features in common. Maranda explains that he was inspired to initiate this project a# er attending performances of the Balinese gamelan in residence at the University of British Columbia; he was struck by the fact that Ba- linese theater uses masks—a device familiar to Maranda from his previous work on ancient Greek theater. -

![Curriculum Vitae [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0393/curriculum-vitae-pdf-1260393.webp)

Curriculum Vitae [PDF]

1 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. John Emigh Professor Theatre, Speech, and Dance and English 2. 3591 Pawtucket Ave Riverside, RI 02915 3. Education: Ph. D. Tulane University (Theatre: Theory and Criticism) 1971 Dissertation: "Love and Honor,1636: A Comparative Study of Corneille's Le Cid and Calderón's Honor Plays" M.F.A. Tulane University (Theatre: Directing) 1967 Thesis: "Analysis, Adaptation, and Production Book of Georg Büchner's Woyzeck" B.A. Amherst College (English and Dramatic Arts) 1964 Thesis: Production of Samuel Beckett's "Waiting for Godot" Additional education and training: 1999-2000 – I Gusti Ngurah Windia (private study, Balinese masked dance]–7/99, 7/01 1983-84 - Intensive workshop in Feldenkrais technique - 1/84 1976-77 - Valley Studio Mime School (corporal mime) - 8/76 - Kristen Linklater and the Working Theatre (intensive workshop in voice and movement for the stage) - 6/77 1974-75 - I Nyoman Kakul (private study, Balinese masked dance -12/74-4/75 1971-72 - American Society for Eastern Arts (Balinese music and dance, Javanese shadow puppetry) - 6-8/72, also 8/76 1967-68 - Columbia University (voice) - 7-8/67 1966-67 - Circle in the Square Theatre School (acting) - 7-8/66 1961-62 - University of Malaga, Spain (curso para estranjeros)-12/61-2/62 4. Professional Appointments: Brown University: 1990- Professor of Theatre, Speech, and Dance and of English 1987- 92 Chairperson, Department of Theatre, Speech, and Dance 1974- 90 Associate Professor of English and Theatre Arts (1986: Theatre, Speech and Dance); Associate Director, University -

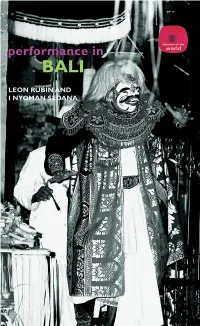

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Theatres of the World Series editor: John Russell Brown Series advisors: Alison Hodge, Royal Holloway, University of London; Osita Okagbue, Goldsmiths College, University of London Theatres of the World is a series that will bring close and instructive contact with makers of performances from around the world. -

It's Role in Greek Society

The Development of Greek Theatre And It’s Role in Greek Society Egyptian Drama • Ancient Egyptians first to write drama. •King Menes (Narmer) of the 32 nd C. BC. •1st dramatic text along mans’s history on earth. •This text called,”the Memphis drama”. •Memphis; Egypt’s capital King Memes( Narmer) King Menes EGYPT King Menes unites Lower and Upper Egypt into one great 30 civilization. Menes 00 was the first Pharaoh. B The Egyptian civilization was a C great civilization that lasted for about 3,000 years. FROM EGYPT TO GREECE •8500 BC: Primitive tribal dance and ritual. •3100 BC: Egyption coronation play. •2750 BC: Egyption Ritual dramas. •2500 BC: Shamanism ritual. •1887 BC: Passion Play of Abydos. •800 BC: Dramatic Dance •600 BC: Myth and Storytelling: Greek Theatre starts. THE ROLE OF THEATRE IN ANCIENT SOCIETY This is about the way theatre was received and the influence it had. The question is of the place given To theatre by ancient society, the place it had in people ’s lives. The use to which theatre was put at this period was new. “Theatre became an identifier of Greeks as compared to foreigners and a setting in which Greeks emphasized their common identity. Small wonder that Alexander staged a major theatrical event in Tyre in 331 BC and it must have been an act calculated in these terms. It could hardly have meaning for the local population. From there, theatre became a reference point throughout the remainder of antiquity ”. (J.R. Green) Tyre Tyre (Latin Tyrus; Hebrew Zor ), the most important city of ancient Phoenicia, located at the site of present-day Sûr in southern Lebanon. -

Drama 204.3 History of Drama and Theatre from 1850 to the Present

Drama 204.3 History of Drama and Theatre From 1850 to the Present History of Theatre, dominantly in the Western Tradition, from the rise of the modern theatre to the present day. Evolution of theatrical production (acting, directing, production, theatre architecture) will be emphasized, with assigned plays being examined largely within the context of the production and performance dynamics of their period. Instructor Moira Day Rm 187, John Mitchell 966-5193 (Off.) 653-4729 (Home) 1-780-466-8957 (emergency only) [email protected] http://www.ualberta.ca/~normang/Pika.html Office Hours MW 11:00 - 1:00 Booklist ***Klaus, Gilbert, Field, ed. Stages of Drama (5th edition). Boston: Bedford/St.Martin’s, 2003. Brockett, Oscar. History of the Theatre (9th edition). Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2003. *** Theatre History Notes Package. Bookstore Grades and Course Information ***Mid-Term 10% Quizzes 10% Response Papers (4 x5%) 20% Group work 20% Participation 10%*** Final Exam 30% ---- 100% I will be in class five minutes ahead of time for consultation, and begin and end lectures on time. I will also return quizzes within TWO class periods after giving them, and return exams within TEN DAYS after giving them. Exams, quizzes and papers not picked up at that class time can be picked up during office hours. Students are expected to be punctual and to submit all classwork on time. Any requests for an extension must be submitted *** ***one week in advance of the formal deadline. ***Unexcused late assignments***, except in the case of certifiable illness or death in the family, will be heavily penalized (10% per day deducted). -

The 1903 Iphigeneia in Tauris in Philadelphia Lee Pearcy Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2008 In the Shadow of Aristophanes: The 1903 Iphigeneia in Tauris in Philadelphia Lee Pearcy Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation L. T. Pearcy, “In the Shadow of Aristophanes: The 1903 Iphigeneia in Tauris in Philadelphia,” In Pursuit of Wissenschaft: eF stschrift für William M. Calder III zum 75. Geburtstag, edd. Stephan Heilen, R. Kirstein, R. S. Smith, S. Trzaskoma, R. van der Wal, and M. Vorwerk. Zurich and New York: Olms, 2008, 327-340. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/105 For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SHADOW OF ARISTOPHANES: THE 1903 IPHIGENEIA IN TAURIS IN PHILADELPHIA Forty years ago in a memorable course on Roman drama at Columbia University I learned that Plautus, Amphitruo, and Seneca, Thyestes, were not only texts for philological study, but also scripts for performance. The in- structor advised us never to neglect any opportunity to attend a staging of an ancient drama; even the most inept production, he said, showed things that reading and study could not reveal.1 With gratitude for that insight and many others given during those undergraduate years and since, I offer this account of a neglected early twentieth-century revival of a Greek tragedy to Professor William M.