The Collective Tongue: an Exploration of Chorus Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Theatre Performance

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF FINE ARTS IN MUSICAL THEATRE WEITZENHOFFER FAMILY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA CREDIT HOURS AND GRADE AVERAGES REQUIRED Musical Theatre For Students Entering the Total Credit Hours . 120-130 Performance Oklahoma State System Minimum Overall Grade Point Average . 2.50 for Higher Education Minimum Grade Point Average in OU Work . 2.50 B737 Summer 2014 through A grade of C or better is required in all courses taken within the College of Fine Arts. Bachelor of Fine Arts Spring 2015 Bachelor’s degrees require a minimum of 40 hours of upper-division (3000-4000) coursework. in Musical Theatre OU encourages students to complete at least 32-35 hours of applicable coursework each year to have the opportunity to graduate in four years. Audition is required for admission to the degree program. General Education Requirements (34-44 hours) Hours Major Requirements (86 hours) Core I: Symbolic and Oral Communication Musical Theatre Performance (14 hours) Musical Theatre Support (14 hours) ENGL 1113, Principles of English Composition 3 MTHR 2122, Auditions 2 MTHR 3143, History of American 3 ENGL 1213, Principles of English Composition, or 3 MTHR 3142, Song Study I 2 Musical Theatre (Core IV) EXPO 1213, Expository Writing MTHR 3152, Song Study II 2 MTHR 4183, Capstone Experience 3 MTHR 3162, Repertoire 2 (Core V) Foreign Language—this requirement is not mandatory if the 0-10 MTHR 3172, Roles 2 Musical Theatre Electives (six of these 8 student successfully completed 2 years of the same foreign MTHR 3182, Musical Scenes I 2 eight hours must be upper-division) language in high school. -

The Characteristics of Greek Theater

The Characteristics of Greek Theater GHS AH: Drama Greek Theater: Brief History n Theater owes much to Greek drama, which originated some 27 centuries ago in 7th century BCE. n Greeks were fascinated with the mystery of the art form. n Thespis first had the idea to add a speaking actor to performances of choral song and dance. The term Thespian (or actor) derives from his name. Greek Theater: Brief History n Greek plays were performed in outdoor theaters, usually in the center of town or on a hillside. n From the 6th century BCE to the 3rd century BCE, we see the development of elaborate theater structures. n Yet, the basic layout of the theater remained the same. Tragedy and Comedy n Both flourished in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, when they were performed, sometimes before 12,000 or more people at religious festivals in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine and the patron of the theater. n Tragedy=dealt with stories from the past n Comedy=dealt with contemporary figures and problems. Introduction to Greek Drama n Video segment: About Drama Complete the worksheet as you watch the video segment. n The masks of comedy and tragedy are emblems of theater today. and they originated in ancient Greece. What are the parts of a Greek theater? What is a Greek Chorus? n The Greek Chorus was a group of poets, singers, and/or dancers that would comment on events in the play. n 12 to 50 members would normally comprise the chorus. n They would explain events not seen by the audience (ex. -

FOUR YEAR PLAN | THEATRE: MUSICAL THEATRE This Is a Sample 4-Year Plan

FOUR YEAR PLAN | THEATRE: MUSICAL THEATRE This is a sample 4-year plan. Students are required to meet with their Academic Advisor each semester. YEAR ONE FALL SEMESTER SPRING SEMESTER Course # Course Name Units Course # Course Name Units THEA 107 Acting I 3 THEA/KINE 133C Musical Theatre Dance I 1 THEA 200C Intro to Theatre 3 SOCI 100C/ANTH 102C/ PSYC Intro to Sociology/Cultural Anthropology/ 3 THEA 134 Musical Literacy for Theatre 2 103C General Psychology CORE 100C Cornerstone 1 NT 101C New Testament Survey 3 THEA 110/106/116 Beginning Costume/Set/Scenic Construction 1 THEA 244 Beginning Musical Theatre Audition 3 ENGL 120C Persuasive Writing 3 THEA 135 Beginning Theatre Movement 2 MUSI 101 OR 102 Basic Voice 1 THEO 101C/103C Foundations of Christian Life/Intro to Theology 3 MUSI 100 Recital Attendance 0 THEA 108A Theatrical Production I 1 THEA 108B Theatrical Production I 1 THEA 132A Theatrical Performance I (if cast) 1-2 THEA 132B Theatrical Performance I (if cast) 1-2 TOTAL 16-18 TOTAL 15-17 YEAR TWO FALL SEMESTER SPRING SEMESTER Course # Course Name Units Course # Course Name Units THEA 320 Lighting Design (must be taken this semester) 3 THEA 309 Costume Design 3 THEA 202C History of Theatre I 3 THEA 207 Acting II 3 OT 201C Old Testament Survey 3 THEA 204C History of Theatre II 3 THEA 239 Makeup Design 3 THEA 344 Intermediate Musical Theatre Audition 3 THEA/KINE 433 Musical Theatre Dance II 1 THEA 208 B Theatrical Production II 1 THEA 220 Musical Theatre Vocal Technique 3 THEA 232 B Theatrical Performance II (if cast) THEA 208 A Theatrical Production II 1 1-2 + Elective THEA 232A Theatrical Performance II 1-2 Dance Class at OCC or Private Dance elective option 1 TOTAL 17-18 TOTAL 16-18 YEAR THREE FALL SEMESTER SPRING SEMESTER Course # Course Name Units Course # Course Name Units THEA 315 Scenic Design (must be taken this semester) 3 THEO 300 Developing a Christian Worldview 3 THEA 360 Dramatic Literature: Script Analysis or Elective 3 ENGL 220 Research Writing 3 POLS 155/HIST 156C U.S. -

The Creative Choreography for Nang Yai (Thai Traditional Shadow Puppet Theatre) Ramakien, Wat Ban Don, Rayong Province

Fine Arts International Journal, Srinakharinwirot University Vol.14 issue 2 July - December 2010 The Creative Choreography for Nang Yai (Thai traditional shadow puppet theatre) Ramakien, Wat Ban Don, Rayong Province Sun Tawalwongsri Abstract This paper aims at studying Nang Yai performances and how to create modernized choreography techniques for Nang Yai by using Wat Ban Don dance troupes. As Nang Yai always depicts Ramakien stories from the Indian Ramayana epic, this piece will also be about a Ramayana story, performed with innovative techniques—choreography, narrative, manipulation, and dance movement. The creation of this show also emphasizes on exploring and finding methods of broader techniques, styles, and materials that can be used in the production of Nang Yai for its development and survival in modern times. Keywords: NangYai, Thai traditional shadow puppet theatre, Choreography, Performing arts Introduction narration and dialogues, dance and performing art Nang Yai or Thai traditional shadow in the maneuver of the puppets along with musical puppet theatre, the oldest theatrical art in Thailand, art—the live music accompanying the shows. is an ancient form of storytelling and entertainment Shadow performance with puppets made using opaque, often articulated figures in front of from animal hide is a form of world an illuminated backdrop to create the illusion of entertainment that can be traced back to ancient moving images. Such performance is a combination times, and is believed to be approximately 2,000 of dance and puppetry, including songs and chants, years old, having been evolved through much reflections, poems about local events or current adjustment and change over time. -

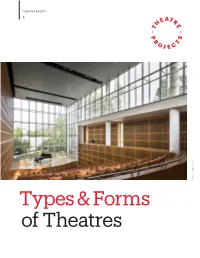

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

History of Theatre the Romans Continued Theatrical Thegreek AD (753 Roman Theatre fi Colosseum Inrome, Which Was Built Between Tradition

History of theatre Ancient Greek theatre Medieval theatre (1000BC–146BC) (900s–1500s) The Ancient Greeks created After the Romans left Britain, theatre purpose-built theatres all but died out. It was reintroduced called amphitheatres. during the 10th century in the form Amphitheatres were usually of religious dramas, plays with morals cut into a hillside, with Roman theatre and ‘mystery’ plays performed in tiered seating surrounding (753BC–AD476) churches, and later outdoors. At a the stage in a semi-circle. time when church services were Most plays were based The Romans continued the Greek theatrical tradition. Their theatres resembled Greek conducted in Latin, plays were on myths and legends, designed to teach Christian stories and often involved a amphitheatres but were built on their own foundations and often enclosed on all sides. The and messages to people who could ‘chorus’ who commented not read. on the action. Actors Colosseum in Rome, which was built between wore masks and used AD72 and AD80, is an example of a traditional grandiose gestures. The Roman theatre. Theatrical events were huge works of famous Greek spectacles and could involve acrobatics, dancing, playwrights, such as fi ghting or a person or animal being killed on Sophocles, Aristophanes stage. Roman actors wore specifi c costumes to and Euripedes, are still represent different types of familiar characters. performed today. WORDS © CHRISTINA BAKER; ILLUSTRATIONS © ROGER WARHAM 2008 PHOTOCOPIABLE 1 www.scholastic.co.uk/junioredplus DECEMBER 2008 Commedia dell’Arte Kabuki theatre (1500s Italy) (1600s –today Japan) Japanese kabuki theatre is famous This form of Italian theatre became for its elaborate costumes and popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. -

Raja Edepus, And: Making of “Raja Edepus.” Lynda Paul

Raja Edepus, and: Making of “Raja Edepus.” Lynda Paul Asian Music, Volume 42, Number 1, Winter/Spring 2011, pp. 141-145 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/amu/summary/v042/42.1.paul.html Access Provided by Yale University Library at 02/05/11 2:36AM GMT Recording Reviews Raja Edepus. Directed and produced by William Maranda. DVD. 92 min- utes. Vancouver BC: Villon Films, 2009. Available from http://www.villon! lms .com. Making of “Raja Edepus.” Directed and produced by William Maranda. DVD. 27 minutes. Vancouver BC: Villon Films, 2008. Available from http://www .villon! lms.com. If, at ! rst glance, ancient Greek tragedy and contemporary Balinese dance- drama seem unlikely theatrical companions, the production Raja Edepus puts any such doubts to rest. Produced by William Maranda with artistic direction by Nyoman Wenten, Raja Edepus is a compelling Balinese rendering of the ancient Sophocles drama, Oedipus Rex. Created for live performance at the Bali Arts Festival in 2006, Raja Edepus is now available to a wider public through two DVDs: one, a recording of the show, and the other, a documentary about the performance’s preparation. " e live production fuses musical and dramatic techniques used in contem- porary Balinese theater with techniques thought to have been used in ancient Greek theater. As Maranda describes on the Making of “Raja Edepus” DVD, the two types of theater—though separated by 2500 years and much of the earth— have signi! cant features in common. Maranda explains that he was inspired to initiate this project a# er attending performances of the Balinese gamelan in residence at the University of British Columbia; he was struck by the fact that Ba- linese theater uses masks—a device familiar to Maranda from his previous work on ancient Greek theater. -

Course Outline

Degree Applicable Glendale Community College October 2013 COURSE OUTLINE Theatre Arts 107 (C-ID Number: THTR 114) Drama Heritage: Play Structure, Form, and Analysis (C-ID Title: Script Analysis) I. Catalog Statement Theatre Arts 107 is a survey of dramatic literature from the classical to the contemporary periods from the structural, stage production, and analytical points of view. The course combines reading, analyzing and understanding play scripts with field trips to local theatres and in-class audio-visual presentations. The student examines the playwright’s methods of creating theatre and learns to distinguish between a play as literature versus a play as performance. Total Lecture Units: 3.0 Total Course Units: 3.0 Total Lecture Hours: 48.0 Total Faculty Contact Hours: 48.0 Prerequisite: None. Note: During the semester, students are expected to attend professional and Glendale Community College Theatre Arts Department productions as a part of the learning process. II. Course Entry Expectations Skill Level Ranges: Reading 5; Writing 5; Listening/Speaking 4; Math 1. III. Course Exit Standards Upon successful completion of the required coursework, the student will be able to: 1. identify representative plays and playwrights of each of the major periods and styles of dramatic literature; 2. demonstrate a respect and appreciation of plays and playwrights, their problems, techniques and relevance to social conditions of the past and present; 3. demonstrate this respect and appreciation through class participation and written assignments dealing with the comparing and contrasting of the various plays and playwrights under study; 4. identify the patterns common to most, if not all, dramatic storytelling. -

History of Greek Theatre

HISTORY OF GREEK THEATRE Several hundred years before the birth of Christ, a theatre flourished, which to you and I would seem strange, but, had it not been for this Grecian Theatre, we would not have our tradition-rich, living theatre today. The ancient Greek theatre marks the First Golden Age of Theatre. GREEK AMPHITHEATRE- carved from a hillside, and seating thousands, it faced a circle, called orchestra (acting area) marked out on the ground. In the center of the circle was an altar (thymele), on which a ritualistic goat was sacrificed (tragos- where the word tragedy comes from), signifying the start of the Dionysian festival. - across the circle from the audience was a changing house called a skene. From this comes our present day term, scene. This skene can also be used to represent a temple or home of a ruler. (sometime in the middle of the 5th century BC) DIONYSIAN FESTIVAL- (named after Dionysis, god of wine and fertility) This festival, held in the Spring, was a procession of singers and musicians performing a combination of worship and musical revue inside the circle. **Women were not allowed to act. Men played these parts wearing masks. **There was also no set scenery. A- In time, the tradition was refined as poets and other Greek states composed plays recounting the deeds of the gods or heroes. B- As the form and content of the drama became more elaborate, so did the physical theatre itself. 1- The skene grow in size- actors could change costumes and robes to assume new roles or indicate a change in the same character’s mood. -

Stagecraft Syllabus

Mr. Craig Duke Theatre Production E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 908-464-4700 ext. 770 Syllabus 2010-2011 Period 2 Course Description: Theatre Production will introduce to the student, both novice and experienced, a practical approach to the technical and production aspects of musical theatre and drama. Students will learn the skills needed to construct scenery, hang and focus lighting instruments, implement a sound system for effects and reinforcement, and scenic artistry, all in a variety of techniques. In conjunction with the Music and Drama Departments, students will take an active role in each of the major productions at NPHS. Additionally, students will be introduced to theatrical design, and will be given an opportunity to draft their own designs for scenery and/or lighting of a theatrical production. Textbooks: There is no textbook for this class. Materials will be distributed in class, along with some notes. Several stagecraft books have been ordered for the NPHS Media Center. They are available in the reference section of the library, and I will refer to them in class from time to time. Most of the material presented comes from The Stagecraft Handbook by Daniel Ionazzi, and from Richard Pilbrow’s Stage Lighting Design. Course Topics: I. Introduction IV. Lighting for the Stage A. A Brief History of Theatre A. Why Light the Stage? B. The Production Team B. Instruments of the Designer C. Safety in the Theatre C. Properties of Light and Dark D. Tools of the Trade D. Color Theories II. Scenic Design for the Stage E. Lighting Design Paperwork A. -

It's Role in Greek Society

The Development of Greek Theatre And It’s Role in Greek Society Egyptian Drama • Ancient Egyptians first to write drama. •King Menes (Narmer) of the 32 nd C. BC. •1st dramatic text along mans’s history on earth. •This text called,”the Memphis drama”. •Memphis; Egypt’s capital King Memes( Narmer) King Menes EGYPT King Menes unites Lower and Upper Egypt into one great 30 civilization. Menes 00 was the first Pharaoh. B The Egyptian civilization was a C great civilization that lasted for about 3,000 years. FROM EGYPT TO GREECE •8500 BC: Primitive tribal dance and ritual. •3100 BC: Egyption coronation play. •2750 BC: Egyption Ritual dramas. •2500 BC: Shamanism ritual. •1887 BC: Passion Play of Abydos. •800 BC: Dramatic Dance •600 BC: Myth and Storytelling: Greek Theatre starts. THE ROLE OF THEATRE IN ANCIENT SOCIETY This is about the way theatre was received and the influence it had. The question is of the place given To theatre by ancient society, the place it had in people ’s lives. The use to which theatre was put at this period was new. “Theatre became an identifier of Greeks as compared to foreigners and a setting in which Greeks emphasized their common identity. Small wonder that Alexander staged a major theatrical event in Tyre in 331 BC and it must have been an act calculated in these terms. It could hardly have meaning for the local population. From there, theatre became a reference point throughout the remainder of antiquity ”. (J.R. Green) Tyre Tyre (Latin Tyrus; Hebrew Zor ), the most important city of ancient Phoenicia, located at the site of present-day Sûr in southern Lebanon.