Shang Han Lun(Cold Damage) 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ling Zhi (Ganoderma)

Chapter 14 – Section 2 Nourishing Herbs that Calm the Shen (Spirit) Ling Zhi (Ganoderma) Pinyin Name: Ling Zhi Literal Name: “spiritual mushroom” Alternate Chinese Names: Mu Ling Zhi, Zi Ling Zhi Original Source: Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing (Divine Husbandman’s Classic of the Materia Medica) in the second century English Name: ganoderma, lucid ganoderma, reishi mushroom Botanical Name: Ganoderma lucidum (Leyss. Ex. Fr.) Karst. (Chi Zhi); Ganoderma japonicum (Fr.) Lloyd. (Zi Zhi) Pharmaceutical Name: Ganoderma 70% Properties: sweet, neutral Channels Entered: Heart, Liver, Lung CHINESE THERAPEUTIC ACTIONS CHEMICAL COMPOSITION 1. Nourishes the Heart and Calms the Shen Ganoderic acid, lucidenic acid, ganoderma acid, gan- (Spirit) odosterone oleic acid.1 Restless shen: Ling Zhi (Ganoderma) nourishes the Heart and strengthens qi and blood to treat Heart and PHARMACOLOGICAL EFFECTS Spleen deficiencies that manifest in insomnia, forgetful- • Antineoplastic: Ling Zhi has been shown to have anti- ness, fatigue, listlessness and poor appetite. neoplastic activity due to its immune-enhancing proper- • Insomnia: combine Ling Zhi with Dang Gui (Radicis ties. The specific effects of Ling Zhi include an increase in Angelicae Sinensis), Bai Shao (Radix Paeoniae Alba), monocytes, macrophages and T-lymphocytes. In addi- Suan Zao Ren (Semen Zizyphi Spinosae) and Long Yan tion, there is also an increased production of cytokine, Rou (Arillus Longan). interleukin, tumor-necrosis-factor and interferon.2 • Cardiovascular: Ling Zhi has been shown to increase 2. Stops Coughing and Arrests Wheezing cardiac contractility, lower blood pressure, and increase Cough and asthma: Ling Zhi dispels phlegm, stops resistance to hypoxia in the cardiac muscles. cough and arrests wheezing. -

Maria Khayutina • [email protected] the Tombs

Maria Khayutina [email protected] The Tombs of Peng State and Related Questions Paper for the Chicago Bronze Workshop, November 3-7, 2010 (, 1.1.) () The discovery of the Western Zhou period’s Peng State in Heng River Valley in the south of Shanxi Province represents one of the most fascinating archaeological events of the last decade. Ruled by a lineage of Kui (Gui ) surname, Peng, supposedly, was founded by descendants of a group that, to a certain degree, retained autonomy from the Huaxia cultural and political community, dominated by lineages of Zi , Ji and Jiang surnames. Considering Peng’s location right to the south of one of the major Ji states, Jin , and quite close to the eastern residence of Zhou kings, Chengzhou , its case can be very instructive with regard to the construction of the geo-political and cultural space in Early China during the Western Zhou period. Although the publication of the full excavations’ report may take years, some preliminary observations can be made already now based on simplified archaeological reports about the tombs of Peng ruler Cheng and his spouse née Ji of Bi . In the present paper, I briefly introduce the tombs inventory and the inscriptions on the bronzes, and then proceed to discuss the following questions: - How the tombs M1 and M2 at Hengbei can be dated? - What does the equipment of the Hengbei tombs suggest about the cultural roots of Peng? - What can be observed about Peng’s relations to the Gui people and to other Kui/Gui- surnamed lineages? 1. General Information The cemetery of Peng state has been discovered near Hengbei village (Hengshui town, Jiang County, Shanxi ). -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

Chen Gui and Other Works Attributed to Empress Wu Zetian

chen gui denis twitchett Chen gui and Other Works Attributed to Empress Wu Zetian ome quarter-century ago, studies by Antonino Forte and Richard S Guisso greatly advanced our understanding of the ways in which the empress Wu Zetian ࣳঞ֚ made deliberate and sophisticated use of Buddhist materials both before and after declaring herself ruler of a new Zhou ࡌʳdynasty in 690, in particular the text of Dayun jing Օႆᆖ in establishing her claim to be a legitimate sovereign.1 However, little attention has ever been given to the numerous political writings that had earlier been compiled in her name. These show that for some years before the demise of her husband emperor Gaozong in 683, she had been at considerable pains to establish her credentials as a potential ruler in more conventional terms, and had commissioned the writing of a large series of political writings designed to provide the ideologi- cal basis for both a new style of “Confucian” imperial rule and a new type of minister. All save two of these works were long ago lost in China, where none of her writings seems to have survived the Song, and most may not have survived the Tang. We are fortunate enough to possess that titled complete with its commentary, and also a fragmentary Chen gui copy of the work on music commissioned in her name, Yue shu yaolu ᑗ ᙕ,2 only thanks to their preservation in Japan. They had been ac- quired by an embassy to China, almost certainly that of 702–704, led టԳ (see the concluding section of thisضby Awata no ason Mahito ொ article) to the court of empress Wu, who was at that time sovereign of 1 See Antonino Forte, Political Propaganda and Ideology in China at the End of the Seventh Century (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale,1976); R. -

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 Introduction It was in the chilly morning of 3 March 2004, hundreds of men and women nervously waited in a magnificent ballroom. Outside the building, more than ten thousand men and women patiently lined up in prepara- tion to welcome their distinguished guests. When presidential candidate Lian Zhang and vice presidential candidate James Song arrived, the crowd’s emotion exploded with thundering applause and repeated shouts of: “Lian-Song, Dongswan!” (which means “winning the election” in Tai- wanese dialect.) Joyful tears ran down on their faces like waterfalls. The solemn host rose and made an inspiring welcome speech. He vehemently accused President Chen Shui-bian for his miserable economic perfor- mance, disasterous social policies, acrimonious ethnic maneuvers, viola- tions of religious rights, sabbotage of democracy, and provocation of war in the Taiwan Straits. Fists clenched, he spoke loudly and with exaggerated body language. Bitterness, anger, and frustration permeated the air and the crowd’s mind. “Only Lian Zhang can save us from these political, social, and economic disasters,” he emphatically concluded. During his speech, the crowd echoed every sentence the host said with deafening applause and “Lian-Song, Dongswan.”1 This might have been any of the ordinary campaign gatherings dur- ing an ordinary election in an ordinary democracy. But this campaign was anything but ordinary. The hall was not at the headquarters of any politi- cal party but at the center of a newly constructed Buddhist temple worth US$ 300 million. The emotional men and women were not devoted party workers or representatives, but monks, nuns, and sincere believers of the otherwise tranquil temple. -

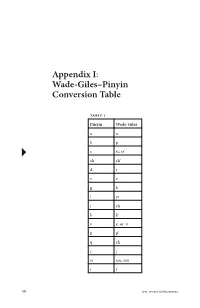

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's Name Dates R Pinyin Romanization of Artist's

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's name ❍ Dates ❍ Pinyin Romanization of Artist's name Artists are listed alphabetically by Wade-Giles. This list is not comprehensive; it reflects the catalogue of visual resource materials offered by AAPD. Searches are possible in either form of Romanization. To search for a specific artist, use the find mode (under Edit) from the pull-down menu. Lady Ai-lien ❍ (late 19th c.) ❍ Lady Ailian Cha Shih-piao ❍ (1615-1698) ❍ Zha Shibiao Chai Ta-K'un ❍ (d.1804) ❍ Zhai Dakun Chan Ching-feng ❍ (1520-1602) ❍ Zhan Jingfeng Chang Feng ❍ (active ca.1636-1662) ❍ Zhang Feng Chang Feng-i ❍ (1527-1613) ❍ Zhang Fengyi Chang Fu ❍ (1546-1631) ❍ Zhang Fu Chang Jui-t'u ❍ (1570-1641) ❍ Zhang Ruitu Chang Jo-ai ❍ (1713-1746) ❍ Zhang Ruoai Chang Jo-ch'eng ❍ (1722-1770) ❍ Zhang Ruocheng Chang Ning ❍ (1427-ca.1495) ❍ Zhang Ning Chang P'ei-tun ❍ (1772-1842) ❍ Zhang Peitun Chang Pi ❍ (1425-1487) ❍ Zhang Bi Chang Ta-ch'ien [Chang Dai-chien] ❍ (1899-1983) ❍ Zhang Daqian Chang Tao-wu ❍ (active late 18th c.) ❍ Zhang Daowu Chang Wu ❍ (active ca.1360) ❍ Zhang Wu Chang Yü [Chang T'ien-yu] ❍ (1283-1350, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu [Zhang Tianyu] Chang Yü ❍ (1333-1385, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu Chang Yu ❍ (active 15th c., Ming Dynasty) ❍ Zhang You Chang Yü-ts'ai ❍ (died 1316) ❍ Zhang Yucai Chao Chung ❍ (active 2nd half 14th c.) ❍ Zhao Zhong Chao Kuang-fu ❍ (active ca. 960-975) ❍ Zhao Guangfu Chao Ch'i ❍ (active ca.1488-1505) ❍ Zhao Qi Chao Lin ❍ (14th century) ❍ Zhao Lin Chao Ling-jang [Chao Ta-nien] ❍ (active ca. -

MONUMENTA SERICA Journal of Oriental Studies

MONUMENTA SERICA Journal of Oriental Studies Vol. LVI, 2008 Editor-in-Chief: ROMAN MALEK, S.V.D. Members of the Monumenta Serica Institute (all S.V.D.): JACQUES KUEPERS – LEO LEEB – ROMAN MALEK – WILHELM K. MÜLLER – ARNOLD SPRENGER – ZBIGNIEW WESOŁOWSKI Advisors: NOEL BARNARD (Canberra) – J. CHIAO WEI (Trier) – HERBERT FRANKE (München) – VINCENT GOOSSAERT (Paris) – NICOLAS KOSS, O.S.B. (Taibei) – SUSAN NAQUIN (Princeton) – REN DAYUAN (Beijing) – HELWIG SCHMIDT-GLINTZER (Wolfenbüttel) – NICOLAS STANDAERT, S.J. (Leuven) Monumenta Serica Institute – Sankt Augustin 2008 Editorial Office Monumenta Serica Institute, Arnold-Janssen-Str. 20 53757 Sankt Augustin, Germany Tel.: (+49) (0) 2241 237 431 • Fax: (+49) (0) 2241 237 486 E-mail: [email protected] • http://www.monumenta-serica.de Redactors: BARBARA HOSTER, DIRK KUHLMANN, ROMAN MALEK Manuscripts of articles, reviews (typewritten and on floppy-disks, see Information for Authors), exchange copies, and subscription orders should be sent to the Editorial Office __________ Taipei Office Monumenta Serica Sinological Research Center 天主教輔仁大學學術研究院 華裔學志漢學研究中心 Fu Jen Catholic University, Hsinchuang 24205, Taipei Hsien E-mail: [email protected] • http://www.mssrc.fju.edu.tw Director: ZBIGNIEW WESOŁOWSKI, S.V.D. ISSN 0254-9948 Monumenta Serica: Journal of Oriental Studies © 2008. All rights reserved by Monumenta Serica Institute, Arnold-Janssen-Str. 20, 53757 Sankt Augustin, Germany Set by the Authors and the Editorial Office, Monumenta Serica Institute. Technical assistance: JOZEF BIŠTUŤ, S.V.D. Printed by DRUCKEREI FRANZ SCHMITT, Siegburg Distribution – Orders – Subscriptions: STEYLER VERLAG, P.O. Box 2460, 41311 Nettetal, Germany Fax: (+49) (0) 2157 120 222; E-mail: [email protected] www.monumenta-serica.de EBSCO Subscription Services, Standing Order Department P.O. -

Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 129 Article 6 2-1-2003 Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans Sheau-yueh J. Chao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chao, Sheau-yueh J. (2003) "Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 129 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss129/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. researching YOUR ASIAN ROOTS CHINESE AMERICANS sheau yueh J chao baruch college city university new york introduction situated busiest mid town manhattan baruch senior colleges within city university new york consists twenty campuses spread five boroughs new york city intensive business curriculum attracts students country especially those asian pacific ethnic background encompasses nearly 45 entire student population baruch librarian baruch college city university new york I1 encountered various types questions serving reference desk generally these questions solved without major difficulties however beginning seven years ago unique question referred me repeatedly each new semester began how I1 find reference book trace my chinese name resource english help me find origin my chinese surname -

NCCAOM Reference of Common Chinese Herbal Formulas

NCCAOM test preparation reference NCCAOM Reference of Common Chinese Herbal Formulas � Ba Zhen Tang (Eight-Treasure Decoction) � Ba Zheng San (Eight-Herb Powder for Rectification) � Bai He Gu Jin Tang (Lily Bulb Decoction to Preserve the Metal) � Bai Hu Tang (White Tiger Decoction) � Bai Tou Weng Tang (Pulsatilla Decoction) � Ban Xia Bai Zhu Tian Ma Tang (Pinellia, Atractylodis Macrocephalae, and Gastrodia Decoction) � Ban Xia Hou Po Tang (Pinellia and Magnolia Bark Decoction) � Ban Xia Xie Xin Tang (Pinellia Decoction to Drain the Epigastrium) � Bao He Wan (Preserve Harmony Pill) � Bu Yang Huan Wu Tang (Tonify the Yang to Restore Five (Tenths) Decoction) � Bu Zhong Yi Qi Tang (Tonify the Middle and Augment the Qi Decoction) � Cang Er Zi San (Xanthium Powder) � Chai Ge Jie Ji Tang (Bupleurum and Kudzu Decoction) � Chai Hu Shu Gan San (Bupleurum Powder to Spread the Liver) � Chuan Xiong Cha Tiao San (Ligusticum Chuanxiong Powder to be Taken with Green Tea) � Da Bu Yin Wan (Great Tonify the Yin Pill) � Da Chai Hu Tang (Major Bupleurum Decoction) � Da Cheng Qi Tang (Major Order the Qi Decoction) � Da Jian Zhong Tang (Major Construct the Middle Decoction) � Dang Gui Bu Xue Tang (Tangkuei Decoction to Tonify the Blood) � Dang Gui Liu Huang Tang (Tangkuei and Six-Yellow Decoction) � Dao Chi San (Guide Out the Red Powder) � Ding Chuan Tang (Arrest Wheezing Decoction) � Du Huo Ji Sheng Tang (Angelica Pubescens and Sangjisheng Decoction) � Du Qi Wan (Capital Qi Pill) � Er Chen Tang (Two-Cured Decoction) � Er Miao San (Two-Marvel Powder) � Er Xian