How Far Was the Loyalty of Muslim Soldiers in the Indian Army More In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Distribution of Mesopotamia Expeditionary Corps, 30 March 1918

Distribution of Mesopotamia Expeditionary Corps 30 March 1918 TIGRIS FRONT General Headquarters in Baghdad 1st Corps: (Headquarters at Samarra) 17th Division: (HQ at Samarra) 34th Infantry Brigade: 2nd Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment 31st Punjabis 1/112nd Infantry 114th Mahrattas No. 129 Machine Gun Company 34th Light Trench Mortar Battery (forming) 34th Small-arm Ammunition Section 34th Brigade Supply & Transport Company 51st Infantry Brigade: 1st Highland Light Infantry 1/2nd Rajputs 14th Sikhs 1/10th Gurkhas No. 257th Machine Gun Company 51st Light Trench Mortar Battery (forming) 51st Small-arm Ammunition Section 51st Brigade Supply & Transport Company 52nd Infantry Brigade: 1/6th Hampshire Regiment 45th Sikhs 84th Punjabis 1/113th Infantry No. 258th Machine Gun Company 52nd Light Trench Mortar Battery (forming) 52nd Small-arm Ammunition Section 52nd Brigade Supply & Transport Company Artillery: 220th Brigade, RFA: (enroute from Basra) 1064th Battery (6 guns) 1066th Battery (6 guns) 403rd Battery (6 guns) 221st Brigade, RFA: (enroute from Basra) 1067th Battery (6 guns) 1068th Battery (6 guns) 404th Battery (6 guns) Engineers: Sirmur Sapper & Miner Company Malerkotia Sapper & Miner Company Tehri-Gahrwal Sapper & Miner Company 1/32nd Sikh Pioneers Divisional Troops: 17th Divisional Signal Company No. 276 Machine Gun Company (in Basra) 17th Divisional Troops Supply & Transport Company No. 3 Combined Field Ambulance 1 No. 19 Combined Field Ambulance No. 35 Combined Field Ambulance No. 36 Combined Field Ambulance No. 1 Sanitary Section -

India and the Great War France & Flanders

INDIAINDIA ANDAND THETHE GREATGREAT WARWAR FRANCEFRANCE && FLANDERSFLANDERS INDIA AND THE GREAT WAR FRANCE & FLANDERS N W E 1914-1915 S Maps not to scale NORWAY An Indian cavalry brigade signal troop at work near Aire in France, 1916. SWEDEN North Sea RUSSIA Baltic Sea Berlin London NETHERLANDS GERMANY BELGIUM Paris AUSTRIA-HUNGARY FRANCE ATLANTIC Black Sea OCEAN ROMANIA SERBIA ITALY BULGARIA N SPAIN Rome ALBANIA British Library: The Girdwood Collection OTTOMAN GREECE W E EMPIRE S Cover Image: Staged photograph of Gorkhas charging a trench near Merville, France. (Source: British Library Girdwood Collection) 2 3 hen the German Army crossed the Belgian frontier on DEPLOYMENT OF THE INDIAN ARMY TO FRANCE 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany, It was decided in London by 6th August, just two days after the declaration Wtaking with it the member countries of the erstwhile British of war, that India would send two divisions to Egypt, and mobilization Empire. Britain’s small regular army, the “Old Contemptibles” that in India commenced straightaway. Even before the BEF had embarked made up the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was exhausted and hard the destination of the Indian Corps was changed to France. pressed by September 1914 when the Indian Corps arrived in France. In August 1914, apart from Britain, the Indian Army was the only trained The Corps filled an essential gap until the British Territorial Army regular army ready to take to the field in the entire Commonwealth. began to arrive at the front in the spring of 1915 (just a few regiments came in 1914) and before the New Army (the volunteer army initiated INTRODUCTION by Lord Kitchener) was ready to take to the field. -

763 19 - 25 June 2015 16 Pages Rs 50

www.nepalitimes.com #763 19 - 25 June 2015 16 pages Rs 50 HANGINGHANGING ONON A girl in Barabise of Sindhupalchok swings in a hammock slung under a container truck that serves as her family’s home. Two months after the earthquake, 2 million Nepalis are living in temporary shelters. JAN MØLLER HANSEN 2 EDITORIAL 19 - 25 JUNE 2015 #763 TROUBLE IN THE RUBBLE Like Krishna Mandir, Nepal is standing but needs more support s the date of the international meeting on earthquake with a backlog of hundreds of tons of relief supplies stuck just aid workers and volunteers who are frustrated, local assistance to Nepal on 25 June nears, the Nepali at warehouses (see page 14-15). And on Wednesday the government officials in the VDCs and DDCs who have been Amedia is suddenly festooned with headlines government tersely announced a ban on all relief material working tirelessly for two months now in relief distribution about the transparency, efficacy and even the necessity after 22 June to stem ‘dependency’ among survivors. Most are disgusted with the lack of support, and the politicisation of international assistance. There are concerns about aid groups would be perfectly happy to hand over their relief of aid in Kathmandu. Some branches of government that are most post-disaster aid being siphoned off by expensive material to the government for distribution if its systems functioning well are getting demoralised by the greed and consultants from donor countries, of lack of coordination, were efficient and equitable, but we have seen they aren’t. lack of a sense of urgency among top politicians. -

4Tli Butin., the Madras Regt. (W.L.I.) MTAEKIERED

THE MADKAS SOIDUE OF 1946—JKMADAK PAKIANATHAN, M.M. 4tli Butin., The Madras Regt. (W.L.I.) MTAEKIERED PRfTHIA'S-.ADAMS The Madras Soldier 1746-1946 By LT.-COL. E. G. PHYTHIAN-ADAMS, O.B.E. Late Madras Regiment and Civil Liaison Officer Madras Presidency and South Indian States 1940—45 • With a ForeMord by SIR CLAUDE AUCHINLECK G.C.B., G.O.I.E., C.S.I., D.S.O., O.B.E,, A.D.C. Commander-in-Chief in India ^"^ ^ \ Printed by the Superintendent Government Press Madras 1948 PRICE, RS. 4-2-0 \rtti-tf \t-T First Published in 1943 Also translated into Tamil Telugu and Malayalam Revised and enlarged edition 1947 ^^7"^- DEDICATED TO THE PEOPLES OF SOUTH INDIA IN GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE OF FORTY-THREE YEARS HAPPY ASSOCIATION 111 FOREWORD I am very glad that Colonel Phytliian-Adams, himself an old soldier of the Madras Army, has written this 'book about the Madras Soldier. When I myself first joined the Indian Army in 1904, the battalion to which I was posted, the 62nd Punjabis, had very recently been raised as. a brand new Punjabi unit on the ashes of the old 2nd Madras Infantry which had an unbroken record of service in many wars from 1759. Lord Kitchener, the Commander-in-Chief at that time, repeated this process with many battalions of the old Madras Line, as he thought they were no longer worth a place in the modern Army of India. There is no doubt that he had some justification for this opinion. But the fault wa_s not that of the Madras soldier. -

Bhupinder Singh Holland

HOW EUROPE IS INDEBTED TO THE SIKHS ? BHUPINDER SINGH HOLLAND With an introduction by Dr Harjinder Singh Dilgeer SIKH UNIVERSITY PRESS How Europe is Indebted To The Sikhs ? By BHUPINDER SINGH HOLLAND ISBN 2-930247-12-6 FOR BIBI SURJIT KAUR (MYMOTHER) & S. NIRMAL SINGH (MY BROTHER) This book is dedicated to my mother who was a pious, religious, noble and humane lady; who was a dedicated Sikh and a role model for every Sikh; and my brother S. Nirmal Singh who laid his life valiantly fighting against armed robbers in Seattle (USA) and saved the lives of his son and a friend. He had learnt this Sikh tradition from Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib who had sacrificed his life so that others may enjoy freedom. Acknowledgement It occurred to me in April 1998 that the tercentenary celebrations of the formation of the Order of Khalsa should be held across Europe. It would be a great honor to witness such a momentous occassion during my life. The first century of the Khalsa passed under the Mugals as it struggled to establish the Khalsa Raj in northern India after defeating the Mugals and stopping and pushing invaders like Ahmed Shah Abdali to the other side of the Kheber Pass. Later, Maharaja Ranjit Singh managed to establish the Sikh kingdom from the river Satluj to the Indus. The second century was passed under the British, as the Punjab was annexed by them through false means after the Anglo-Sikh Wars, and Sikhs struggled to regain their lost sovereignity. It was my opinion that the best celebration would be to remember martyrs of the 20th century. -

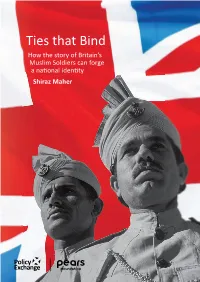

Policy Exchange Ties That Bind: How the Story Of

Muslims have a long and distinguished record of service in the British armed forces. Exchange Policy But this record has been almost completely obliterated in recent years by the competing narratives of the Far Right and of hardline Islamists. Both blocs, for their own ideological reasons, seem to assert that one cannot be both a loyal Briton and a good Muslim at the same time. Ties that Bind In Ties that Bind: How the story of Britain’s Muslim Soldiers can forge a national Bind Ties that How the story of Britain’s identity, former Islamist Shiraz Maher recaptures this lost history of Muslim service to the Crown. He shows that in the past the Muslim authorities in India successfully Muslim Soldiers can forge faced down Islamist propaganda and emotive appeals to their confessional a national identity obligations – and made it clear that there were no religious reasons for not fighting for the British Empire. This was particularly the case in the First World War, even Shiraz Maher when this country was locked in combat with the Ottoman Caliphate. Maher shows that this collective past constitutes the basis of a new shared future – which can endure in no less testing circumstances. It also forms the basis for enhanced recruitment of Muslims to the armed forces, without political preconditions attached. Shiraz Maher is a Senior Research Fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) at King’s College London and a former activist for the Islamist group Hizb ut Tahrir. £10.00 ISBN: 978-1-907689-09-3 Policy Exchange Clutha House 10 Storey’s Gate London SW1P 3AY www.policyexchange.org.uk Ties that Bind How the story of Britain’s Muslim Soldiers can forge a national identity Shiraz Maher Policy Exchange is an independent think tank whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas which will foster a free society based on strong communities, personal freedom, limited government, national self-confidence and an enterprise culture. -

At the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. BETWEEN SELF AND SOLDIER: INDIAN SIPAHIS AND THEIR TESTIMONY DURING THE TWO WORLD WARS By Gajendra Singh Thesis submitted to the School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History 2009 ! ! "! ! Abstract This project started as an attempt to understand rank-and-file resistance within the colonial Indian army. My reasons for doing so were quite simple. Colonial Indian soldiers were situated in the divide between the colonizers and the colonized. As a result, they rarely entered colonialist narratives written by and of the British officer or nationalist accounts of the colonial military. The writers of contemporary post-colonial histories have been content to maintain this lacuna, partly because colonial soldiers are seen as not sufficiently ‘subaltern’ to be the subjects of their studies. -

Order of Battle of the Indian Army Corps in France, 1914-15

Appendix I: Order of Battle of The Indian Army Corps in France, 1914-15 Note: This order of battle represents the Indian Corps as it was from the end of 1914 to the end of 1915. From early 1916, the two infantry divisions served in Mesopotamia. In the autumn of 1914, the cavalry were organized as a single division, consisting of the Ambala, Lucknow and Secunderabad Cavalry Brigades. Units of the British Army are indicated with an asterisk. 3rd (LAHORE) INFANTRY DIVISION 7th (Ferozepore) Brigade 1st and 2nd Connaught Rangers (one unit)* 4th London (Territorials)* 9th Bhopal Infantryl 57th Rifles (Frontier Force) 89th Punjabis2 129th Baluchis 8th (Jullundur) Brigade 1st Manchesters * 4th Suffolks (Territorials)* 40th Pathans3 47th Sikhs 59th Rifles (Frontier Force) 9th (Sirhind) Brigade 1st Highland Light Infantry* 4th Liverpool Regiment (Special Reserve)* 15th Sikhs4 1Ilst Gurkhas 1I4th Gurkhas 359 360 Indian Voices of the Great War Divisional Troops 15th Lancers 34th Sikh Pioneers 20th and 21st Companies, Sappers and Miners Artillery 5th, 11th and 18th Brigades, RFA * 109th Heavy Battery* 7th (MEERUT) INFANTRY DIVISION 19th (Dehra Dun) Brigade 1st Seaforth Highlanders * 1I9th Gurkhas 1I2nd Gurkhas 6th Jats 20th (Garhwal) Brigade 2nd Leicesters * 3rd London (Territorials) * 1I39th Garhwal Rifles 2/39th Garhwal Rifles5 2/3rd Gurkhas 2/8th Gurkhas6 21st (Bareilly) Brigade 2nd Black Watch * 4th Black Watch (Territorials)* 41 st Dogras 7 58th Rifles 69th Punjabis8 I 25th Rifles9 Divisional Troops 4th Cavalry 107th Pioneers 3rd and 4th Companies, -

What Is This Project About?

What is this project about? This project aims to increase public awareness of South Asian soldiers of the British Indian Army who won the Victoria Cross during World War One. Thanks to the support from Heritage Lottery Fund for allowing the project to able to stage a free public exhibition at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. The images and artefacts have been kindly loaned from National Army Museum in London and Imperial War Museum. This leaflet is designed to accompany the exhibition and some of its text and details can also be found on exhibition panels and labels. Please note that information in the booklet and on the exhibition boards might be different. The information on soldiers, in this booklet, has been provided by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The original documents regarding the Indian Army were destroyed. How do the Victoria Cross and the Indian How did the British Indian Army develop Order of Merit compare to each other? between 1858 and 1914? During the 18th and 19th centuries the British East Indian Company came to dominate South Asia (what is now modern India, Pakistan and Bangladesh), ruling two thirds directly and one third through client princes. In 1857 a major revolt by South Asian soldiers employed by the Company was crushed ruthlessly by the British (it is traditionally known as the Indian Mutiny in Britain). The Company’s lands were transferred to the Crown and Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1877. Museum, London) Museum, A new British Indian Army was formed, carefully recruited from South Asian peoples the British Army Museum, London) Museum, Army regarded as most warlike with numbers balanced so that no one religion dominated. -

Black Commonwealth Service Personnel in the British Armed

The British Armed Forces during the World Wars All the pictures are from the Imperial War Museums Collections. ‘IWM supports and encourages research into our collections and they are open to the public’. Share and Reuse Many items are available to be shared and re-used under the terms of the IWM Non- Commercial License. The photographs used in this exhibition are ‘share and reuse’ items. Imperial War Museums IWM London IWM North IWM Duxford “Our London museum “Visit our iconic “Visit this historic airfield tells the stories of museum in Manchester and museum of aviation people’s experiences of and explore how war history and discover the stories of people who modern war from WW1 affects people’s lives.” lived and worked at RAF to conflicts today.” Duxford.” Free admission Free admission See website for ticket IWM North prices IWM London The Quays Lambeth Road Trafford Wharf Road IWM Duxford London SE1 6HZ Manchester M17 1TZ Cambridgeshire CB22 4QR 10am - 6pm every day 10am - 5pm every day 10am - 6pm every day www.iwm.org.uk • The slides will show soldiers from different countries which fought for or with the British armed forces. A slide will indicate which country is next. • Where there are slides from both World Wars WWI slides will show first. • The presentation is set as manual so you change each slide with the click of the mouse. This is to make sure that you have had the time you need to look at each image and read any text at your own speed. Some of the Countries who fought for or with the British Armed Forces in both World Wars • Australia • Canada • Malaysia and Singapore • Ceylon (Sri Lanka) • New Zealand • Czechoslovakia (Czech • Nigeria Rep/Slovakia) • Persia (Iran) • Ethiopia • Poland • Guyana • Sudan • Indian Subcontinent • Trinidad (Pakistan/Bangladesh/Nepal) • Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) • Iraq • South Africa • Jamaica • Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) • Kenya British Colonial Regiments – see regiments of the Indian Sub-Continent below. -

Indian Army 1914

THE ARMY IN INDIA – JULY 1914 C.-in-C. Gen Sir H. Beauchamp Duff HQ – Calcutta NORTHERN ARMY – Lieut-Gen Sir J. Willcocks HQ – Murree 1ST PESHAWAR DIVISION – Maj-Gen C.J. Blomfield HQ – Cherat Division & Area Troops: Chitral & Drosh: 2/1st (King George’s Own) Gurkha Rifles (The Malaun Regiment) Section, 25th Mtn Btry Section, No.11 Coy. 2nd Sappers & Miners Malakand: 38th Dogras Half Bn, 112th Infantry Detachment, Frontier Garrison Artillery Chakdara: Half Bn, 51st Sikhs (FF) Detachment, Frontier Garrison Artillery Dargai: HQ & half Bn, 51st Sikhs (FF) Peshawar Infantry Brigade – Maj-Gen C.F.G. Young Peshawar Cantonment: HQ & half Bn, 2/The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) HQ & half Bn, 1/Royal Sussex Regiment 14th King George’s Own Ferozepore Sikhs 21st Punjabis [minus detachment] 72nd Punjabis Detachment, Punjab Vol. Rifles AF 1st Duke of York’s Own Lancers (Skinner’s Horse) 1 Detachment, Punjab Light Horse AF 75 Btry RFA [III Brigade RFA] 72 Heavy Btry RGA Detachment, Frontier Garrison Artillery No.1 Coy. 1st Sappers & Miners Abazai: Detachment, Guides 1 Attached for training to Risalpur Cavalry Brigade. 1 Cherat Cantonment: Half Bn, 2/The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) Half Bn, 1/Royal Sussex Regiment Jamrud Cantonment: Detachment, 21st Punjabis Detachment, Frontier Garrison Artillery Shabqadar: Detachment, 46th Punjabis Nowshera Brigade – Brig-Gen H.V. Cox Nowshera Cantonment: Detachment, 1/Durham Light Infantry 24th Punjabis 46th Punjabis [minus detachment] 82nd Punjabis HQ & half Bn, 112th Infantry Detachment, Punjab Vol. Rifles AF HQ XVI Brigade RFA; 89, 90 & 91 Btrys RFA 25th Mtn Btry [minus section] Risalpur Cavalry Brigade – Maj-Gen J.G.