Master Document Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Film Documentary About Carry on Sergeant Trenton's Heyday As

Volume 23 Number 1 www.hastingshistory.ca Issue 321 January 2018 A Film Documentary About Carry On Sergeant Trenton’s Heyday as Hollywood North By Bill Kennedy This year celebrates the 100th anniversary of Hollywood North, a colloquialism for Trenton from the days when it was the movie-making capital of Canada. At the Historical Society’s November public event, the history of that glamorous period was brought back to life in a book and film presentation by Doug Knutson of Wind- swept Productions and author Peggy Dy- mond Leavey. Doug Knutson and Peggy Dymond Leavey show off the poster of When she set out to research her book The Hollywood North. Photo by Bill Kennedy Movie Years, Leavey decided that she would write it from the perspective of how the town’s movie-making industry affected local father, a World War I veteran himself and a noted citizens. Back then, American movie stars walking British cartoonist who had gained fame with his Trenton streets and attending local hockey games drawings of “Old Bill,” a curmudgeonly soldier of was not an extraordinary sight. Roles as extras were the trenches who helped boost the morale of British frequently available. During the making of the clas- and allied troops. The assistant director was pioneer- sic World War I silent film Carry On Sergeant, one ing Canadian filmmaker Gordon Sparling. In Knut- of the extras Leavey interviewed recalled seeing son’s documentary film about Carry On Sergeant, some of his own friends walking across the Trenton Sparling, who was in his nineties at the time, remi- bridge wearing German army uniforms. -

Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Magazine Special Collections and University Archives Fall 2006 Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine Recommended Citation Florida International University Division of University Relations, "Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006" (2006). FIU Magazine. 4. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine/4 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Magazine by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2006 20/20 VISION President Modesto A. Maidique crowns his 20-year anniversary at FIU with an historic accomplishment, winning approval for a new College of Medicine. Also in this issue: Alumna Dawn Ostroff ’80 FIU honors alumni College of Business takes the helm of a at largest-ever Administration expansion new television network Torch Awards Gala garners support THE 2006 GOLDEN PANTHERS FOOTBALL SEASON WILL BE THE HOTTEST ON RECORD WITH THE HISTORIC FIRST MATCHUP AGAINST THE UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI AT THE ORANGE BOWL. DON'T MISS A MOMENT, CALL FOR YOUR TICKETS TODAY: 1 -866-FIU-GAME FIU Golden Panthers 2006 Season Aug Middle Tennessee A 7 p.m. September 9* South Florida A 7 p.m. Raymond James Stadium, Tampa September 16* Bowling green H 6 p.m. Sept * Maryland Arkansas State Parents weekend North Texas University of Miami A TBA Orange Bowl, Miami October .21 Alabama A TBA INfoverrtber Louisiana-Monroe H 7 p.m. -

Science Fiction and Fantasy Posters

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8z3252z No online items Science fiction and fantasy posters Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Science fiction and fantasy MS 260 1 posters Descriptive Summary Title: Science fiction and fantasy posters Date (inclusive): circa 2000-2012 Collection Number: MS 260 Extent: 0.42 linear feet(20 flat file folders) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: The collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy posters consists of oversize tv/movie posters from the Science Fiction and Fantasy genre. Languages: The collection is in English. Access This collection is unprocessed. Please contact Special Collections & University Archives regarding the availability of materials for research use. Publication Rights Copyright Unknown: Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.). In addition, the reproduction, and/or commercial use, of some materials may be restricted by gift or purchase agreements, donor restrictions, privacy and publicity rights, licensing agreement(s), and/or trademark rights. Distribution or reproduction of materials protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the copyright owners. To the extent other restrictions apply, permission for distribution or reproduction from the applicable rights holder is also required. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. -

ALL Code Sheets

Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Cursive Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. The cursive letters should be connected when spelling a word. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD WRITTEN IN CODE EX. S P E L L I N G 1. ___________________ __________________________________________ 2. ___________________ __________________________________________ 3. ___________________ __________________________________________ 4. ___________________ __________________________________________ 5. ___________________ __________________________________________ 6. ___________________ __________________________________________ 7. ___________________ __________________________________________ 8. ___________________ __________________________________________ 9. ___________________ __________________________________________ 10. __________________ __________________________________________ Created by K. S. Spencer Name: _________________________ Code Name: _________________________ Alien Nation® Print Alphabet In the science fiction movie “Alien Nation” the Tenctonese people have an alphabet that corresponds to our alphabet. They even have print and cursive versions of their language. Use the alphabet to spell 10 of your spelling words. The word “SPELLING” is done for you as an example. LIST WORD -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

Challenging ESPN: How Fox Sports Can Play in ESPN's Arena

Challenging ESPN: How Fox Sports can play in ESPN’s Arena Kristopher M. Gundersen May 1, 2014 Professor Richard Linowes – Kogod School of Business University Honors Spring 2014 Gundersen 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship ESPN has with the sports broadcasting industry. The study focuses on future prospects for the industry in relation to ESPN and its most prominent rival Fox Sports. It introduces significant players in the market aside from ESPN and Fox Sports and goes on to analyze the current industry conditions in the United States and abroad. To explore the future conditions for the market, the main method used was a SWOT analysis juxtaposing ESPN and Fox Sports. Ultimately, the study found that ESPN is primed to maintain its monopoly on the market for many years to come but Fox Sports is positioned well to compete with the industry behemoth down the road. In order to position itself alongside ESPN as a sports broadcasting power, Fox Sports needs to adjust its time horizon, improve its bids for broadcast rights, focus on the personalities of its shows, and partner with current popular athletes. Additionally, because Fox Sports has such a strong regional persona and presence outside of sports, it should leverage the relationship it has with those viewers to power its national network. Gundersen 2 Introduction The world of sports is a fast-paced and exciting one that attracts fanatics from all over. They are attracted to specific sports as a whole, teams within a sport, and traditions that go along with each sport. -

Conference Program

Thirty-Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts ConferenCe Program No taping of sessions may take place without signed permission from an elected officer of the IAFA Executive Board and from all individuals participating in the session. Wednesday, March 14 11:00am-6:00pm 9:00am-6:00pm Registration Desk IAFA Book Exhibit and Sales Main Floor Augusta A/B Coordinator: Karen Hellekson Director: Mark Wingenfeld Audio-Visual Acrobatics coordinated by the incomparable Sean Nixon 2:30-3:15 p.m. Pre-Opening Refreshment Ballroom Foyer 3:30-4:15 p.m. Opening Ceremony Ballroom Host: Donald E. Morse, Conference Chair Welcome from the President: Sherryl Vint Opening Panel: Mary Shelley’s Legacies Moderator: Gary K. Wolfe Nike Sulway, John Kessel, Fred Botting Wednesday, 4:30-6:00pm Sessions 1-11 C 1. (IF/SF/VPAA) Magic and Science Fiction from the Perso- 2. (FTFN/CYA) Constructing Identity in Wonder Tales P O Arabic World and Lovecraft Chair: Linda J. Lee I V N E Chair: Debbie Felton University of Pennsylvania E University of Massachusetts-Amherst Navigating Enfreaked Disabilities in the Realms of Victorian Orange Princesses, Emerald Sorcerers and Dandy Demons: Fairy Tales The Fantastic in Persianate Miniature Painting and Epic Literature Victoria Phelps Zahra Faridany-Akhavan Saginaw Valley State University Independent Scholar With Eyes both Brown and Blue: Making Monsters in Lost Girl The Vault of Heaven: Science Fiction’s Perso-Arabic Origins Jeana Jorgensen Peter Adrian Behravesh Indiana University/Butler University University of Southern Maine The Dark Arts and the Occult: Magic(k)al Influences on/of H. -

Runaway Film Production: a Critical History of Hollywood’S Outsourcing Discourse

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository RUNAWAY FILM PRODUCTION: A CRITICAL HISTORY OF HOLLYWOOD’S OUTSOURCING DISCOURSE BY CAMILLE K. YALE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor John C. Nerone, Chair and Director of Research Professor James W. Hay Professor Steven G. Jones, University of Illinois at Chicago Professor Cameron R. McCarthy ABSTRACT Runaway production is a phrase commonly used by Hollywood film and television production labor to describe the outsourcing of production work to foreign locations. It is an issue that has been credited with siphoning tens of millions of dollars and thousands of jobs from the U.S. economy. Despite broad interest in runaway production by journalists, politicians, academics, and media labor interests, and despite its potential impact on hundreds of thousands—and perhaps millions—of workers in the U.S., there has been very little critical analysis of its historical development and function as a political and economic discourse. Through extensive archival research, this dissertation critically examines the history of runaway production, from its introduction in postwar Hollywood to its present use in describing the development of highly competitive television and film production industries in Canada. From a political economic perspective, I argue that the history of runaway production demonstrates how Hollywood’s multinational media corporations have leveraged production work to cultivate goodwill and industry-friendly trade policies across global media markets. -

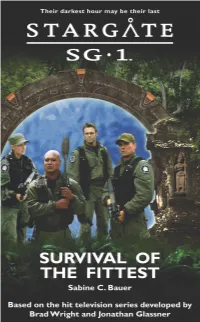

Survival of the Fittest

Survival of the Fittest Sabine C. Bauer An original publication of Fandemonium Ltd, produced under license from MGM Consumer Products. Fandemonium Books PO Box 795A Surbiton Surrey KT5 8YB United Kingdom Visit our website: www.stargatenovels.com © 2011 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. All Rights Reserved. Photography and cover art: Copyright ©1997-2011 MGM Television Entertainment Inc./ MGM Global Holdings Inc. All Rights Reserved. METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER Presents RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON In STARGATE SG-1™ AMANDA TAPPING CHRISTOPHER JUDGE and MICHAEL SHANKS as Daniel Jackson Executive Producers ROBERT C. COOPER BRAD WRIGHT MICHAEL GREENBURG RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON Developed for Television by BRAD WRIGHT & JONATHAN GLASSNER STARGATE SG-1 © 1997-2011 MGM Television Entertainment Inc./MGM Global Holdings Inc. STARGATE: SG-1 is a trademark of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All rights reserved. WWW.MGM.COM No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written consent of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. To Tanya—beta extraordinaire and the one who‟s responsible for Everything! CONTENTS Prolog Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Prolog The childlike face— she‟d been a child, first and foremost, a smart, needy, tantrum-throwing teenager who‟d made an awful mistake— never moved. -

Bringing Penance Back to the Penitentiary: Using the Sacrament of Reconciliation As a Model for Restoring Rehabilitation As a Priority in the Criminal Justice System

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 40 Number 3 Volume 40, Spring 2001, Number 3 Article 5 Bringing Penance Back to the Penitentiary: Using the Sacrament of Reconciliation as a Model for Restoring Rehabilitation as a Priority in the Criminal Justice System John Celichowski, O.F.M Cap. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRINGING PENANCE BACK TO THE PENITENTIARY: USING THE SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION AS A MODEL FOR RESTORING REHABILITATION AS A PRIORITY IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM JOHN CELICHOWSKI, O.F.M CAP.* INTRODUCTION In recent years, many Americans have become familiar with the names of places where the power of evil and the depths of human depravity have been revealed in their fullness: Littleton, Rwanda, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, and East Timor. Others, however, have experienced the shadows of the human soul in ways less graphic but more terrifyingly personal than the pages of the New York Times or the vivid imagery of CNN could ever convey. They have encountered these shadows in the form of crime in cities and suburbs, in neighborhoods and on highways, and in the workplace as well as in the home. They have endured * Pastor, St. Benedict the Moor Church, Milwaukee, Wis. -

Island REP ER

Gypsy 'kingpin' Chamber town Second council arrested meeting candidate declares page 15 FEBRUARY 4,1999 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 5 island 40 PAGES REP -, j " J ER 100 YEARS AND COUNTING cited for nudity B Related column/page 7 By Gwenda Hiett-Clements News Editor As of Tuesday, Sanibel police had ticket- ed six nude sunbathers in the Bowman's Beach/Silver Key area. Officers issued three notice-to-appear citations for breach of peace/disorderly conduct Sunday, two list Wednesday and one Tuesday. The action came in response to repeat*, d complaints by citizens of nude sunbathing in the area, the island's "unofficial nude beach." At the Jan. 19 Sanibel City Council t> See Nudity, page 4 PU&Ua (1 to r) Catherine Nawnann, Kim Egsley, and Don vice counter Tuesday* afternoon. The three are Im'press'ive Jewel share a few laughs at Bailey's customer ser- long-time employees of the 100-year-old store. improvements Bailey's celebrates a century of business To our readers: • Business inside store turns 1 year old/page 13 cents a pound; veal, turkey and beef were 10 cents a pound; and For the next two weeks, we will be bacon was 12 cents a pound. In produce, potatoes were 35 cents rebuilding our press units, which will result By Gwenda Hiett-Clements a dozen, oranges and lemons 15 cents a dozen, eggs were 12 cents in better print quality for the Island News Editor a dozen and butter was 18 cents a pound. Reporter. However, people on Sanibel, mostly farmers when Frank The work will be done over the week- Back in 1899 when Bailey's General Store, or the Sanibel Bailey opened the store, didn't need those items.