Struggling, Closed and Closing Churches Research Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Division. Binbrook, Saint Mary, Binbrook, Saint Gabriel. Croxby

2754 East Division. In the Hundred of Ludborough. I Skidbrooke cum Saltfleetj Brackenborough, ] Somercotes, North, Binbrook, Saint Mary, 1 Somercotes, South, Binbrook, Saint Gabriel. Covenham, Saint Bartholomew, ; ; Covenham, Saint Mary, Stewton, Croxby, 1 1 TathweU, Linwood, Fotherby, ', Grimsby Parva, Welton on the Wolds, Orford, jWithcall, Rasen, Middle, Ludborough, , Ormsby, North, Utterby, Wykeham, Rasen, Market, I Yarborough. Stainton le Vale, Wyham cum Cadeby. Tealby, In the Hundred of Calceworth. In t?ie Hundred of Wraggoe. Thoresway, I Aby with Greenfield, Thorganby, Benniworth, Biscathorpe, f Anderby, Walesby, Brough upon Bain cum Girsby, JAlford, Willingham, North. Hainton, Belleau, Ludford Magna, Ludford Parva, Beesby in the Marsh, In the Hundred of Wraggoe. "Willingham, South. Bilsby with Asserby, an$ Kirmond le Mire, Thurlby, Legsby with Bleasby and CoIIow, In the Hundred of Gartree. Claythorpe, Calceby, SixhiUs, ' ' •: .Asterby, Cawthorpe, Little, Torrington, East. Baumber, Belchford, Cumberworth, Cawkwell, Claxby, near Alford, Donington upon Bain, Farlsthorpe, In the Hundred of Bradley Gayton le Marsh, Haverstoe, West Division. Edlington, Goulceby, Haugh, Aylesby, Heningby, Horsington, Hannah cum Hagnaby, Barnoldby le Beck, Langton by Horncastle, Hogsthorpe, Huttoft, Beelsby, Martin, Legburn, Bradley, Ranby, Mablethorpe, Cabourn, Scamblesby, Mumby cum Chapel Elsey and Coats, Great, Stainton, Market, Langham-row, Coates, Little, Stennigot, Sturton, Maltby le Marsh, Cuxwold, Thornton. Markby, Grimsby, Great, Reston, South, Hatcliffe with Gonerby, In the Hundred of Louth Eske. Rigsby with Ailby, Healing, Alvingham, Sutton le Marsh, Irby, Authorpe, Swaby with White Pit, Laceby, Burwell, Saleby with Thoresthorpe, Rothwell, Carlton, Great, Carlton Castle, Strubby with Woodthorpe; Scartho, Theddlethorpe All Saints, Carlton, Little, Theddlethorpe Saint Helen, Swallow. Conisholme, Thoresby, South, East Division. Calcethorpe, Cockerington, North, or Saint Tothill, Trusthorpe, Ashby cum Fenby, Mary, . -

51W Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

51W bus time schedule & line map 51W Louth View In Website Mode The 51W bus line (Louth) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Louth: 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM (2) Market Rasen: 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 51W bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 51W bus arriving. Direction: Louth 51W bus Time Schedule 28 stops Louth Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM Market Place, Market Rasen Market Place, Market Rasen Civil Parish Tuesday 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM Demand Responsive Area, Walesby Wednesday 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM Demand Responsive Area, Tealby Thursday 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM Friday 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM Demand Responsive Area, North Willingham Saturday 8:00 AM - 6:00 PM Demand Responsive Area, Thorganby Demand Responsive Area, Swinhope Demand Responsive Area, Benniworth 51W bus Info Direction: Louth Demand Responsive Area, Market Stainton Stops: 28 Trip Duration: 111 min Demand Responsive Area, Donington on Bain Line Summary: Market Place, Market Rasen, Demand Responsive Area, Walesby, Demand Responsive Area, Tealby, Demand Responsive Area, Demand Responsive Area, South Willingham North Willingham, Demand Responsive Area, Thorganby, Demand Responsive Area, Swinhope, Demand Responsive Area, Hainton Demand Responsive Area, Benniworth, Demand Responsive Area, Market Stainton, Demand Demand Responsive Area, Stenigot Responsive Area, Donington on Bain, Demand Responsive Area, South Willingham, Demand Demand Responsive Area, Asterby Responsive Area, Hainton, -

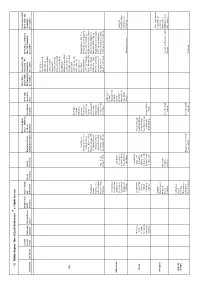

CD80 Green Infrastructure Data Web Table 2012

GI Within Approx 1km of Each Settlement * = Public Access Protected Open Green Space Green Space (20 Green Space (500 Coastal Children and Church Yards Space - additional Sport and (2Ha in 300m - Ha in 2km - NE Green Space (100 Ha in Ha in 10km - NE Access Parks and Amenity Green Youth and Green Sports Natural and Semi- to others Recreational Recreation NE Standards) Standards) 5km - NE Standards) Standards) Settlement Allotments Points Gardens Space Provision Cemeteries Corridors Provision natural Green Space identified Footpath Area Accessible * Accessible * Accessible * Accessible * Mother and Greenfield Woods SNCI (49 ha) * Swinn Wood SNCI (25 ha), Tothill Wood LWS (78.5ha), Calceby Marsh SSSI (9.346 ha) Calceby Beck, Ava Maria to Belleau Bridge LWS (3.969ha) and with Aby Calceby Beck, East Marsh LWS The Public (1.073ha) Ing Holt Footpath LWS (1.831ha) Network is Calceby Beck, *Kew Wood good and West Bank *Burwell Wood LWS (119 Woodland Trust Site would allow Grassland LWS ha) together with Haugham (0.26ha), Moors predominantly (1.471ha) *Calceby Wood LWS (75.873ha), Wood LWS ( 0.75ha), off road Beck Tributary LWS Haugham Slates Grassland *Aby Burial *Belleau Springs LWS walking around (1.309ha) *Swaby LWS (8.355ha) Eight Acre Ground (1.588ha) Disused most of the Valley SSSI Trust Plantation LWS (2.09 ha), (0.27ha), * St Railway North of village and a Reserve (3.591ha) Haugham Horseshoe LWS John the Baptist Swinn Wood LWS round walk to provide an area of (3.027ha) and Haugham Church Belleau Aby Fishing (1.527ha), * Swinn Belleau of 3 km 22.59ha part of Pasture Wood South LWS (0.215ha) Pond (0.75ha) Wood SNCI (25 ha), (1.75 miles). -

Alford's War Memorial

Alford War Memorials TF 455755 Alford is both a parish and a small but ancient market town. A small brook runs through the parish, which is 8 miles northeast of Spilsby and 13 miles southeast of Louth, and sits only six miles from the North Sea. The parish covers about 1,100 acres. © John Readman The parish church is of St. Wilfred’s, which is close to the centre of the town. Inside the church are several war memorials. These consist of the following:- Roll of Honour World War 1 Roll of Honour World War 2 A memorial to Richard James Sinclair in Northern Ireland 1972 A stained glass window for Maurice Nelson Baron Outside the church is the town’s war memorial, a cross upon four steps. The church is often open to the public, and all the memorials are easy to find within the church. They are maintained in a very good condition. © Lincolnshire Family History Society 2009 Roll of Honour World War One © John Readman This is a parchment Roll of Honour with the letters beautifully inscribed and decorated. A close - up of the names reveals the following: Almond to Hall © John Readman © Lincolnshire Family History Society 2009 Hammond to Riggall © John Readman Rhodes to Yates © John Readman There are 52 names altogether on the above list which is shown below: © Lincolnshire Family History Society 2009 ALFORD ROLL OF HONOUR IN THE GREAT WAR Bernard Almond: Sapper: Royal Engineers: November 8 1918 Charles Arrowsmith: Private, Liverpool Scottish: April 9th, 1917 Arthur Stephen Baggley: Lance Corporal, 3rd Lincolnshire Regiment: April 3rd, 1918 Maurice Nelson Baron: Flight Sub Lieutenant, Royal Naval Air Service: August 15th, 1917 John William Bell: Private, Royal Marine Light Infantry, HMS Hague: September 22nd 1914 Charles William Blades: Private, West Yorkshire Regiment: April 23rd, 1918 Sydney Brewer: Corporal, 1/19 London Regiment (St. -

Lincolnshire. L

fKELLY'S. 6 LINCOLNSHIRE. L. • Calceworth Hundred (Wold Division) :-Alford, Beesby- Well Wapentake :-Brampton, Bransby, Gate Burton, in-the-Marsh, Bilsby, Claxby, Farlsthorpe, Hannah, Maltby Fenton, Kettlethorpe, Kexby, Knaith, Marton, Newton le-Marsh, Markby, Rigsby, Saleby, Strubby, Ulceby, Well, upon-Trent, Normanby, Stowe, Sturton, Upton, and Willoughby, and Withern. Willing ham. Candleshoe Wapentake, Marsh Division :-Addlethorpe, Wraggoe Wapentake, East Division :-Barwith (East and Burgh-in-the-Marsh, Croft, Friskney, Ingoldmells, North West), Benniworth, Biscathorpe, Burgh-upon-Hain, Hainton, olme, Orby, Skegness, Wainfleet All Saints, Wainfleet St. Hatton, Kirmond-le-Mire, Langton-by-Wragby, Ludford Mary, and Winthorpe. Magna, Ludford Parva, Panton, Sixhills, Sotby, South Candleshoe Wapentake, Wold Division :-Ashby-by-Part Willingham, and East Wykeham. ney, Bratoft, Candlesby, Dalby, Driby, Firsby, Gunby, St. Wraggoe Wapentake, West Division: -Apley, Bardney, Peter, lrby-in-the-Marsh, Partney, Scremby, ~kendleby, Bullington, Fulnetby, Goltho, Holton Beckering, Legsby, Great Steeping, Sutterby, and Welton-in-the-Marsh. Lissinton, Newhall, Rand, Snelland, Stainfield, Stainton-by. Corringham Wapentake :-Blyton, Cleatham, Corringham, Langworth, Torrington (East and West), Tupholme, Wick East Ferry, Gainsborough, Grayingham, Greenhill, Heap en by, and Wragby. ham, Hemswell, Kirton-in-Lindsey, Laughton, Lea, Morton, Yarborough Wapentake, East Division :-Bigby, Brockles N orthorpe, Pilham, Scatter, Scotton, Southorpe, Spring by, Croxton, Habrough, East Halton, Immingham, Keelby, thorpe, East Stockwith, Walkerith and Wildsworth. Killingholme (North and South), Kirmington, Limber Mag. Gartree Wapentake, North Division :-Asterby, Baumber na, Riby, and Stallingborough. or Bamburgh, Belchford, Cawkwell, Donington-npon-Bain, Yarborough Wapentake, North Division :-Barrow-upon Edlington, Goulsby or Goulceby, Hemingby, Market Stain Humber, Booby, Elsham, South Ferriby, Goxhill, Horkstow, ton, Ranby, Scamblesby, Stenigot, and Great Sturton. -

Lincolnshire Remembrance User Guide for Submitting Information

How to… submit a war memorial record to 'Lincs to the Past' Lincolnshire Remembrance A guide to filling in the 'submit a memorial' form on Lincs to the Past Submit a memorial Please note, a * next to a box denotes that it needs to be completed in order for the form to be submitted. If you have any difficulties with the form, or have any questions about what to include that aren't answered in this guide please do contact the Lincolnshire Remembrance team on 01522 554959 or [email protected] Add a memorial to the map You can add a memorial to the map by clicking on it. Firstly you need to find its location by using the grab tool to move around the map, and the zoom in and out buttons. If you find that you have added it to the wrong area of the map you can move it by clicking again in the correct location. Memorial name * This information is needed to help us identify the memorial which is being recorded. Including a few words identifying what the memorial is, what it commemorates and a placename would be helpful. For example, 'Roll of Honour for the Men of Grasby WWI, All Saints church, Grasby'. Address * If a full address, including post code, is available, please enter it here. It should have a minimum of a street name: it needs to be enough information to help us identify approximately where a memorial is located, but you don’t need to include the full address. For example, you don’t need to tell us the County (as we know it will be Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire or North East Lincolnshire), and you don’t need to tell us the village, town or parish because they can be included in the boxes below. -

Lincolnshire and the Danes

!/ IS' LINCOLNSHIRE AND THE DANES LINCOLNSHIRE AND THE DANES BY THE REV. G. S. STREATFEILD, M.A. VICAR OF STREATHAM COMMON; LATE VICAR OF HOLY TRINITY, LOUTH, LINCOLNSHIRE " in dust." Language adheres to the soil, when the lips which spake are resolved Sir F. Pai.grave LONDON KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH & CO., r, PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1884 {The rights of translation and of reproduction arc reserved.) TO HER ROYAL HIGHNESS ALEXANDRA, PRINCESS OF WALES, THIS BOOK IS INSCRIBED BY HER LOYAL AND GRATEFUL SERVANT THE AUTHOR. A thousand years have nursed the changeful mood Of England's race,—so long have good and ill Fought the grim battle, as they fight it still,— Since from the North, —a daring brotherhood,— They swarmed, and knew not, when, mid fire and blood, made their or took their fill They —English homes, Of English spoil, they rudely wrought His will Who sits for aye above the water-flood. Death's grip is on the restless arm that clove Our land in twain no the ; more Raven's flight Darkens our sky ; and now the gentle Dove Speeds o'er the wave, to nestle in the might Of English hearts, and whisper of the love That views afar time's eventide of light PREFACE. " I DO not pretend that my books can teach truth. All I hope for is that they may be an occasion to inquisitive men of discovering truth." Although it was of a subject infinitely higher than that of which the following pages treat, that Bishop Berkeley wrote such words, yet they exactly express the sentiment with which this book is submitted to the public. -

List of Rectors at Welton Compiled by Phyllis Smith, 1960-1

List of Rectors at Welton compiled by Phyllis Smith, 1960-1 Gilbert 1190 Chaplain of Welton In Stenton's Danelaw Charters, p114, Gilbert chaplain of Welton witnessed a quitclaim of service for a tenement in Grainthorpe. Peter of Bath before 1219 Ormsby Priory Richard of Sutton 1224 resigned 1239-40 John of St Edmunds 1239-40 John de Ry died 1265 Holles, p173 Gosberkirke Joňes de Ry quondam rector hujus Ecclesiae et d[omi]nus hujus Villae, eujus ače propitietus deus. Amen Thomas of Northfleet 15th November 1265 – died 1317 [Liber Cleri. 1576] Master Henry of Donington 27th December 1317 – died 1340 Nicholas by Newton-by-Pocklington 7th May 1340 – resigned 1346 John of Retford 7th May 1346 – died 1349 [plague?] William of Fotherby 8th July 1349 – died 1349 [plague?] Robert of Friskney 9th September 1349 – died 1352 Robert of Immingham 4th January 1353 – died 1354 Henry of Usselby (Oselby) 6th May 1354 – resigned 1355 for the sake of an exchange with the church of Claxby by Normaby. (Ep.Reg. IX, fol. 114d) Henry of Kelstern 17th February 1355 – resigned 27th February 1380 for the sake of an exchange with William of Wilton rector of the church of Besthamstede in the diocese of Salisbury (Ep.Reg. X folios 101d,102) Henry of Kelstern mentioned in Liber Clericum [L.C.] William of Wilton 27th February 1380 Thomas Asterby died 1420. Lincolnshire Church Notes, Gervase Hollis, AD 1634-42 Lincs. Record Soc. 'Upon a Freestone in ye middle of the Quire. Hic jacet DŇS Thomas Asterby dudum Rector de Welton juxta Ludam qui obit [blank] die mensis [blank] anno dňi mccccxx cuius animae propicietur deus. -

Lincolnshire. Born Castle

DIBECTOBY.] LINCOLNSHIRE. BORN CASTLE. 247 :Massingberd Rev. William Oswald M.A. Rectory, South Moorby, Panton, Ranby, Revesby, Roughton, Salmonby, Ormsby, Alford Scamblesby,Scrafield,Scrivelsby,Somersby,Sotby,Stainton :Massingberd-Mundy Charles Francis esq. D.L. South Ormsby Market, Stixwould, Sturton Great, Tattershall,Tattershall hall, Alford Thorpe, Tetford, Thimbleby, Thornton, Toynton High, Otter Francis e-c;;q. lii.A. Ranby hall, Wragby Toynton Low, Tumby, Tupholme, Waddingworth,Wilksby Short John Hassard esq. D.L. Edlington park, Horncastle Wildmore (part of), Winceby, Wispington, Wood Enderby Stanhope James Banks esq. D.L. Revesby Abbey, Boston & Woodhall Wright Rev. Canon Arthur M. A. rector, Coningsby, Boston Certified Bailiffs under the Law of Distress Amendment Clerk to the Magistrates, Charles Dee, 14 South street Act, 1888 :-John Chimley, 3 Stanhope terrace; Walter Petty Sessions are held at the Court house, North street, Booth Parish, Old Bank chambers, Bull ring; Charles every saturday at 12 noon Matthias Hodgetts, 7 W ong ; William Henry Pogson, The petty sessional division contains the following places in Coningsby the Horncastle soke :-Ashby West, Coningsby, Haltham, Horncastle Excelsior Brass Band, Martin Wright Shaw, Horncastle, Langriville, Ma.reha.m-le-Fen, Ma.reha.m-le bandmaster, 20 Foundry street . Hill, Moorby, Roughton, Thimbleby, Thornton-le-Fen, Orchestral Band, Herbert Carlton, sec. 8 High street Tointon High, Tointon Low, Wildmore, Wilksby, Wood County Police Station, W ong, Thomas Stevenitt, superin· Enderby. In the hundred of Gartree :-Asterby, Baumber, tendent, I sergeant & 3 constables Belcbford, Bucknall, Cawkwell, Dalderby, Edlington, Horncastle Public Dispensary, North street, Gen. Charles Gautby, Goulceby, Hemingby, Horsington, Kirkby-super Elmhirst c. B. -

THE PARISH of the ASTERBY GROUP NEWSLETTER March-April 2021

THE PARISH OF THE ASTERBY GROUP NEWSLETTER March-April 2021 24 Deadline for next Newsletter All articles and adverts for inclusion in the May/ June 2021 newsletter to be Date Event Description with Sue (Tel 01507313545 or email: [email protected]) by 1 Mar St Davids Day Patron saint of Wales Thursday 15th April 2021 at the very latest. Please let me have your items written out or typed, as you would like them to appear, and as early as 14 Mar Mothers Day Originated on the day when Christians visited possible, please don’t wait until the deadline. the church they were baptised in (mother To place an advert please contact Sue on the above number. Please note church) and end up meeting their mothers on there is a new price list for various sizes of advert and also a choice of black the way and white or colour. Again Sue has these details on request. 17 Mar St Patricks Day Patron saint of Ireland All items on behalf of the church have no charge. Any other events or adverts will have a charge. This is minimal and helps to maintain and 28 Mar British Summer Time Clocks go forward 1 hour develop your newsletter. begins 28 Mar Palm Sunday Sunday before Easter and marks Jesus’ trium- Contact Sue; [email protected] phal entry into Jerusalem 1 Apr April Fools Day 1 Apr Maundy Thursday Thursday before Easter. It commemorates the SOUTH WOLDS GROUP OFFICE washing of the feet and last supper of Jesus Tel: 01507 525600 Christ with the apostles Based in St Mary’s Church, Horncastle. -

THE PARISH of the ASTERBY GROUP NEWSLETTER January-February 2021

THE PARISH OF THE ASTERBY GROUP NEWSLETTER January-February 2021 20 Deadline for next Newsletter Girls Coventry Eagle bicycle, 24” wheels, suit 7-10 year old £10 All articles and adverts for inclusion in the March/April 2021 newsletter to Classic black ladies bicycle, 26” wheels £10 be with Sue (Tel 01507313545 or email: [email protected]) by Mans roadster bicycle, 26” wheels £20 Monday 15th February 2021 at the very latest. Please let me have your items written out or typed, as you would like them to appear, and as early Mans mountain bike, 26” wheels, suit 6 ft rider £150 as possible, please don’t wait until the deadline. Fibreglass Pyranha kayak, 9ft 3” with helmets and wet gear Offers To place an advert please contact Sue on the above number. Please note Honda rotary roller mower HR216, gwo + handbook Offers there is a new price list for various sizes of advert and also a choice of black Oleo-Mac chainsaw + handbook Offers and white or colour. Again Sue has these details on request. 2-Stroke hedge trimmer + handbook, needs attention Offers All items on behalf of the church have no charge. Any other events or adverts will have a charge. This is minimal and helps to maintain and 01507 343777 Jim, Goulceby develop your newsletter. 4 used wooden kitchen chairs, pine colour £30 ono SOUTH WOLDS GROUP OFFICE Computer desk, beech colour £25 ono Tel: 01507 525600 Framed limited edition print of a Springer Spaniel by John Trickett, 741 of Based in St Mary’s Church, Horncastle. -

2002 No. 1588 CORONERS the Lincolnshire

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2002 No. 1588 CORONERS The Lincolnshire (Coroners’ Districts) Order 2002 Made - - - - - 13th June 2002 Laid before Parliament 17th June 2002 Coming into force - - 1st August 2002 Whereas: (1) the Council of the County of Lincolnshire have, in pursuance of section 4(2) of the Coroners Act 1988(a) and after due compliance with the provisions of the Coroners (Orders as to Districts) Rules 1927(b), submitted to the Secretary of State a draft Order providing for the alteration of the existing division of that county into coroners’ districts; and (2) the Secretary of State has made such modifications of the draft Order as he thinks fit; Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by section 4(2) of that Act, hereby makes the following Order: 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Lincolnshire (Coroners’ Districts) Order 2002. (2) This Order shall come into force on 1st August 2002. (3) This Order shall not have effect in relation to any inquest begun before the day on which it comes into force or to any post-mortem examination which, before that day, a coroner has directed or requested a medical practitioner to make. 2. The following areas, namely— (a) the existing coroners’ districts of Lincoln, Grantham and Sleaford (as constituted by the Lincolnshire (Coroners’ Districts) Order 1974(c)), and (b) the part of the existing Louth coroner’s district (as so constituted) which consists of the parishes of East Barkwith, Hatton, Langton-by-Wragby, Panton, West Barkwith, West Torrington and Wragby, all in the district of East Lindsey, shall be amalgamated to form a single coroner’s district called the West Lincolnshire Coroner’s District.