Eyeglasses for Close-Up Work Close-Up Glasses Are Not Everyday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sightsavers Policy on Recycled Spectacles

DRAFT POSITION PAPER ADJUSTABLE SPECTACLES Position statement There are an estimated 670 million cases of blindness or vision impairment (153 million people with impaired far visioni and 517 million people with impaired near visionii) simply because they are unable to access an appropriate eye examination and spectacles. Far vision impairment alone costs $269billion a year in lost productivity.iii The massive volume of cases, and consequent scale of disability and economic impact caused by uncorrected refractive error (URE) has lead to various attempts to provide short-cut refractive care. Adjustable spectacles, with the optical power either set in an eye examination or self-adjusted, have been promoted by several companies and organizations as a potential solution.iv IAPB recognises the good intentions behind these short-cuts and spectacle technology but advises that its members and other parties engaged in promoting eye health should exercise caution with or avoid adjustable spectacles at this time. In deciding whether and how to use adjustable spectacles in future, the following areas should be considered. Considerations Sustainability It is critical that refractive services are provided in a manner that contributes to affordable, high quality eye care for all patients irrespective of social standing. Isolated provision of spectacles is detrimental to the human resources and service delivery systems that are necessary for sustainable eye care services, and so should be avoided whenever possible. • Adjustable spectacles that are affordable, comfortable, cosmetically acceptable and optically accurate may have a role contributing to sustainability when used by trained personnel within the recognised service delivery system of the jurisdiction • Adjustable spectacles used in a way (e.g. -

Introduction the Human

Physics 1CL ·OPTICAL INSTRUMENTS AND THE EYE SPRING 2010 Introduction Most of the subject material in this lab can be found in Chapter 25 of Serway and Faughn. In this lab, you will make images of images using lenses and the optical bench (Experiment A). IT IS IMPERATIVE THAT YOU READ CHAPTER 25 BEFORE COMING TO LAB! You will study your own eye as an optical instrument and measure the distance on your retina from the fovea to the “blind spot” (Experiment B). You will also study a model of the eye, and examine the ability of the lens to bring an object into focus at different distances. You will examine how an abnormal eyeball causes blurred vision and how to correct this (Experiment C). There is only one station with the model of the human eye. Whenever that station becomes available, take a few minutes at that station to perform Experiment C. The Human Eye The figure shows a cross section of a human eye. Light is refracted at the surface of the cornea, and is refracted again as it passes through the “crystalline” lens. In a normal eye, light is perfectly focused on the receptors in the retina where signals are generated in nerve fibers and transmitted to the brain. An inverted image is formed on the retina, but the brain “expects” this as normal and is wired to recognize this as normal. Unless you are studying details of the function of the eye, we can consider it to be a single lens (where the focal length can be varied), and a fixed distance from the lens to the retina where we would prefer to make sharply focused images. -

A Virtual Try-On System for Prescription Eyeglasses

Feature Article A Virtual Try-On System for Prescription Eyeglasses Qian Zhang and Yu Guo ■ Nanyang Technological University Pierre-Yves Laffont, Tobias Martin, and Markus Gross ■ ETH Zurich ision-correcting eyeglasses have improved We present a system for virtually trying on pre- the lives of millions of people. Eyeglasses scription eyeglasses. Our system acts as a virtual significantly affect the wearer’s appear- mirror, allowing users to try on a variety of eye- Vance, and the selection of new pairs of eyeglasses is glasses with corrective lenses based on their pre- largely based on how the glasses look when wearers scription (see Figure 2). We use an image sequence try them on. However, an often overlooked fact is of the user without eyeglasses as input, along with that corrective lenses introduce distortion caused the user’s eyeglasses prescription and a 3D model by the refraction effect. As Figure 1 illustrates, the of the desired eyeglasses frame. Our system gen- eyes of a person wearing correc- erates a 3D representation of the corrective lenses tive lenses for nearsightedness mounted into the eyeglasses frame and modifies the Corrective lenses introduce appear smaller compared with video sequence to virtually insert the eyeglasses us- distortion caused by the wearing nonprescription lenses, ing image-based rendering. This approach simulates refraction effect, which whereas the eyes of a person the distortion introduced by the prescription lenses changes the wearer’s wearing lenses for farsightedness and gives users a better idea of how they would look appearance. To give users a appear larger. when wearing the new pair of eyeglasses. -

Prescription Companion

PRESCRIPTION COMPANION ©2012Transitions Optical inc. ophthalmic lens technical reference JUBILEE YEAR 2012 E -Edition 7 www.norville.co.uk Introduction and Page Index The Norville Companion is a supporting publication for our Prescription Catalogue, providing further technical details, hints and ideas gleaned from everyday experiences. TOPIC Page(s) TOPIC Page(s) Index 2 - 3 Part II Rx Allsorts Lens Shapes 4 - 6 Lens Forms 49 Effective Diameter Chart 7 Base Curves 50 - 51 Simplify Rx 8 Aspherics 52 - 53 Ophthalmic Resins 9 Free-form Digital Design 54 Indices of Ophthalmic lenses - Resin 10 Compensated Lens Powers 55 - 56 Polycarbonate 11 Intelligent Prism Thinning 57 - 58 Trivex 12 - 13 Superlenti - Glass 59 Resin Photochromic Lenses 14 Superlenti - Resin 60 Transitions Availability Check List 15 V Value / Fresnels 61 Nupolar Polarising Lenses 16 E Style Bifocal / Trifocal 62 Drivewear Lenses 17 - 18 Photochromic / Glazing / Prisms 63 UV Protective Lenses 19 Lens Measures 64 Norville PLS Tints 20 Sports 65 Tinted Resin Lenses 21 3D Technology Overview 66 Mid and High Index Resins Tintability 22 Rx Ordering 67 Norlite Tint Transmission Charts 23 - 25 Order Progress 68 Norlite Speciality Tinted Resins 26 - 31 Rx Order Form 69 Norlite Mirror Coating 32 Queries 70 Reflection Free Coating 33 - 34 Optical Heritage 71 F.A.Q. Reflection Free Coatings 35 - 37 Rx House - Change afoot? 72 - 73 Indices of Ophthalmic Lenses - Glass 38 Remote Edging 74 Glass Photochromic Lenses 38 Remote edging - F.A.Q. 75 Speciality Absorbing Glass 39 Quality Assurance -

Intraocular Lenses and Spectacle Correction

MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE INTRAOCULAR LENSES, SPECTACLE CORRECTION AND IRIS PROSTHESIS POLICY NUMBER MP-6.058 Original Issue Date (Created): 6/2/2020 Most Recent Review Date (Revised): 6/9/2020 Effective Date: 2/1/2021 POLICY PRODUCT VARIATIONS DESCRIPTION/BACKGROUND RATIONALE DEFINITIONS BENEFIT VARIATIONS DISCLAIMER CODING INFORMATION REFERENCES POLICY HISTORY I. POLICY Intraocular Lens Implant (IOL) Initial IOL Implant A standard monofocal intraocular lens (IOL) implant is medically necessary when the eye’s natural lens is absent including the following: Following cataract extraction Trauma to the eye which has damaged the lens Congenital cataract Congenital aphakia Lens subluxation/displacement A standard monofocal intraocular lens (IOL) implant is medically necessary for anisometropia of 3 diopters or greater, and uncorrectable vision with the use of glasses or contact lenses. Premium intraocular lens implants including but not limited to the following are not medically necessary for any indication, including aphakia, because each is intended to reduce the need for reading glasses. Presbyopia correcting IOL (e.g., Array® Model SA40, ReZoom™, AcrySof® ReStor®, TECNIS® Multifocal IOL, Tecnis Symfony and Tecnis SymfonyToric, TRULIGN, Toric IO, Crystalens Aspheric Optic™) Astigmatism correcting IOL (e.g., AcrySof IQ Toric IOL (Alcon) and Tecnis Toric Aspheric IOL) Phakic IOL (e.g., ARTISAN®, STAAR Visian ICL™) Replacement IOLs MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE INTRAOCULAR LENSES, SPECTACLE CORRECTION AND IRIS PROSTHESIS POLICY NUMBER -

Benjamin Franklin People Mentioned in Walden

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN BENJAMIN “VERSE-MAKERS WERE GENERALLY BEGGARS” FRANKLIN1 Son of so-and-so and so-and-so, this so-and-so helped us to gain our independence, instructed us in economy, and drew down lightning from the clouds. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Franklin was distantly related to Friend Lucretia Mott, as was John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Adams, and Octavius Brooks Frothingham. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF WALDEN: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN WALDEN: In most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this PEOPLE OF it will be retained; that, in respect to egotism, is the main WALDEN difference. We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking. I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well. Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN WALDEN: But all this is very selfish, I have heard some of my PEOPLE OF townsmen say. I confess that I have hitherto indulged very little WALDEN in philanthropic enterprises. I have made some sacrifices to a sense of duty, and among others have sacrificed this pleasure also. There are those who have used all their arts to persuade me to undertake the support of some poor family in town; and if I had nothing to do, –for the devil finds employment for the idle,– I might try my hand at some such pastime as that. -

A Breakthrough in Myopia Control for Your Child

USER GUIDE FOR MiYOSMART MiYOSMART OPTOMETRIC PROTOCOL FOR MiYOSMART MiYOSMART MiYOSMART: A SMART APPROACH TO MYOPIA MiYOSMART The user guide identies what new MiyoSmart wearers should take note of during the adaptation period. To ensure maximized benets of MiyoSmart are experienced, it is recommended to follow the optometric protocol. If you had a way to halt or slow down the progression of myopia, surely you would want to know how. Adaption to new lenses MiyoSmart delivers on this promise and lls a rapidly growing market need. MiyoSmart is an innovative 1ST VISIT 1. It always takes time to get used to your new lenses. The time needed really depends on the individual but wearers can ophthalmic lens for myopia control developed by Hoya Vision Care in cooperation with its research expect about one to two weeks to adapt. collaborator, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU). Engineered specically to correct myopic During the rst visit, all visual functions of the child should be assessed to get a clear overview of the current status. A few 2. During the adaptation time, the wearer should avoid: factors are examined to ascertain if the wearer is suitable for MiyoSmart. refractive error and slow down myopia progression, MiyoSmart comes to market at a time when the 1 It is also essential to know the child and his/her parents' ocular and optical history. incidence of myopia is on the rise. Preliminary investigation will also have to be done, where it is compulsory to conduct the following tests and examinations: An estimated 5 billion Research shows that Intensive sport Operating any Using the new lenses Using them on high people, or activities, e.g. -

Types of Contact Lenses and Their Characteristics1

3 ■ Types of Contact Lenses and Their Characteristics1 The basic categories of contact lenses currently acetate butyrate [CAB], PMMA-silicone, and in use are the original hard (polymethylmethacry- silicone). There are variations within each group, late [PMMA]) lenses, soft hydrogels (hydro- but their respective properties are similar enough xymethylmethacrylate [HEMA] and other mate- to consider them as essentially the same type of rials), and gas-permeable hard lenses (cellulose lenses. HARD PMMA LENSES As discussed in the previous chapter, hard rial and safe for use in the eye. It can be molded PMMA lenses were the first lenses introduced or lathed into lenses with a high degree of preci- onto the market, and corneal PMMA lenses simi- sion. Once made, PMMA lenses can be reworked lar to those currently in use have been available and modified to customize them to an individual’s since the early 1950s. Compared to later types of requirements. The result is a safe lens of excellent lenses, PMMA lenses can be difficult to adapt to, visual properties which very closely conforms to and perhaps as many as half of the people fitted patient requirements. PMMA lenses require min- do not become long-term wearers. Since PMMA imal use of cleaning, soaking, and wetting solu- is not water- or gas-permeable, wearers must rely tions. They may be tinted to reduce excessive light on the “tear pump” action of the eye to provide sensitivity, to make them easier to find when oxygen to the covered portion of the cornea. As dropped, or for appearance reasons. They are the wearer blinks, tear interchange occurs from durable, can be renewed by polishing away mi- outside the lens to beneath it, providing the nec- nor surface scratches, and often last 5 to 7 years essary oxygen. -

Lenses and Optics

PHYS 1400: Physical Science for General Education Laboratory Manual LENSES AND OPTICS INTRODUCTION If you (or your cat) wear glasses or contact lenses, you are already familiar with the science of optics. Whether you realize it or not, you understand the idea of a focal point. You are very aware when an image is out of focus (no glasses) or in focus (put your glasses back on). You even know the difference between a real and a virtual image, although you have probably never said to yourself, “I wish that the real image formed by the lens in my eye was better focused on my retina!” Or may be you have. OBJECTIVES ๏ Identify the differences between concave and convex lenses ๏ Use the lens equation to Steampunk Cat is equipped for any ocular emergency. determine the focal length of a convex lens Convex lenses are converging lenses. ๏ Construct ray diagrams to accurately show how an image is formed Concave lenses are diverging lenses. ๏ Demonstrate the difference between a near– and far–sighted eye, and show how each vision problem can be corrected ACTIVITY 1: CONVERGING AND DIVERGING LENSES ๏ Use the converging and diverging lenses to observe objects around the room. ๏ Try to use both as magnifying glasses to enlarge text. ๏ While observing a single object, move the lens toward and away from your eye. Do this for both types of lens. ๏ Try observing objects using various combinations of lenses: two converging, two diverging, one of each. QUESTIONS 1. Which type of lens can you use to magnify text? What happens to the magnified image as you draw the lens farther from the text? 2. -

Relationship Between Lenticular Power and Refractive Error in Children with Hyperopia

Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Relationship between lenticular power and refractive error in children with hyperopia Takeshi Tomomatsu Objectives: To evaluate the contribution of axial length, and lenticular and corneal power to Shinjiro Kono the spherical equivalent refractive error in children with hyperopia between 3 and 13 years of Shogo Arimura age, using noncontact optical biometry. Yoko Tomomatsu Methods: There were 62 children between 3 and 13 years of age with hyperopia (+2 diopters Takehiro Matsumura [D] or more) who underwent automated refraction measurement with cycloplegia, to measure Yuji Takihara spherical equivalent refractive error and corneal power. Axial length was measured using an optic biometer that does not require contact with the cornea. The refractive power of the lens Masaru Inatani was calculated using the Sanders-Retzlaff-Kraff formula. Single regression analysis was used Yoshihiro Takamura to evaluate the correlation among the optical parameters. For personal use only. Department of Ophthalmology, Results: There was a significant positive correlation between age and axial length P( = 0.0014); Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Fukui, Fukuiken, Japan however, the degree of hyperopia did not decrease with aging (P = 0.59). There was a significant negative correlation between age and the refractive power of the lens (P = 0.0001) but not that of the cornea (P = 0.43). A significant negative correlation was observed between the degree of hyperopia and lenticular power (P , 0.0001). Conclusion: Although this study is small scale and cross sectional, the analysis, using noncontact biometry, showed that lenticular power was negatively correlated with refractive error and age, indicating that lower lens power may contribute to the degree of hyperopia. -

Writing Freedom Write Yourresponse Beforesharingyourideas

UNIT 1 Writing Freedom Words That Shaped a Nation Discuss It In what ways is the concept of “no taxation without representation” central to America’s identity as a nation? Write your response before sharing your ideas. © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All rights reserved. or its affiliates. Inc., Education, © Pearson Boston Tea Party SCAN FOR 2 MULTIMEDIA UNIT 1 UNIT INTRODUCTION ESSENTIAL QUESTION: LAUNCH TEXT ARGUMENT MODEL What is the meaning of freedom? Totally Free? WHOLE-CLASS SMALL-GROUP INDEPENDENT LEARNING LEARNING LEARNING Historical Perspectives EXPOSITORY NONFICTION ESSAY Focus Period: 1750–1800 from America’s from Democracy Is A New Nation Constitution: Not a Spectator A Biography Sport Akhil Reed Amar Arthur Blaustein with Helen Matatov ANCHOR TEXT: FOUNDATIONAL DOCUMENT GRAPHIC NOVEL SPEECH Declaration of COMPARE from The Reflections on the Independence United States Bicentennial of Thomas Jefferson Constitution: the United States A Graphic Constitution MEDIA CONNECTION: John F. Kennedy Reads the Adaptation Thurgood Marshall Declaration of Independence Jonathan Hennessey and Aaron McConnell POETRy ANCHOR TEXT: FOUNDATIONAL DOCUMENTS AUTOBIOGRAPHY Speech to the Young Speech to the Preamble to the from The Interesting Progress-Toward Constitution Narrative of the Life Gwendolyn Brooks Gouverneur Morris of Olaudah Equiano Olaudah Equiano The Fish Bill of Rights Elizabeth Bishop James Madison letter | biography SHORT STORY ANCHOR TEXT: SPEECH Letter to John Adams The Pedestrian Speech in the Abigail Adams Ray Bradbury Convention Benjamin Franklin from Dear Abigail: The Intimate Lives MEDIA CONNECTION: The U. S. Constitution and Revolutionary Ideas of Abigail POLITICAL DOCUMENT Adams and Her Two from the Iroquois MEDIA: IMAGE GALLERY Remarkable Sisters Constitution Diane Jacobs The American Dekanawidah, translated Revolution: by Arthur C. -

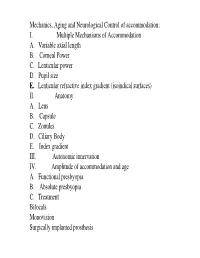

I. Multiple Mechanisms of Accommodation A. Variable Axial Length B

Mechanics, Aging and Neurological Control of accommodation: I. Multiple Mechanisms of Accommodation A. Variable axial length B. Corneal Power C. Lenticular power D. Pupil size E. Lenticular refractive index gradient (isoindical surfaces) II. Anatomy A. Lens B. Capsule C. Zonules D. Ciliary Body E. Index gradient III. Autonomic innervation IV. Amplitude of accommodation and age A. Functional presbyopia B. Absolute presbyopia C. Treatment Bifocals Monovision Surgically implanted prosthesis Course title - (VS217) Oculomotor functions and neurology Instructor - Clifton Schor GSI: James O’Shea, Michael Oliver & Aleks Polosukhina Schedule of lectures, exams and laboratories : Lecture hours 10-11:30 Tu Th; 5 min break at 11:00 Labs Friday the first 3 weeks Examination Schedule : Quizes: January 29; February 28 Midterm: February 14: Final March 13 Power point lecture slides are available on a CD Resources: text books, reader , website, handouts Class Website: Reader. Website http://schorlab.berkeley.edu Click courses 117 class page name VS117 password Hering,1 First Week: read chapters 16-18 See lecture outline in syllabus Labs begin this Friday, January 25 Course Goals Near Response - Current developments in optometry Myopia control – environmental, surgical, pharmaceutical and genetic Presbyopia treatment – amelioration and prosthetic treatment Developmental disorders (amblyopia and strabismus) Reading disorders Ergonomics- computers and sports vision Virtual reality and personal computer eye-ware Neurology screening- Primary care gate keeper neurology, systemic, endocrines, metabolic, muscular skeletal systems. Mechanics, Aging and Neurological Control of accommodation : I. Five Mechanisms of Accommodation A. Variable axial length B. Corneal Power and astigmatism C. Lenticular power D. Pupil size & Aberrations E. Lenticular refractive index gradient (isoindical surfaces) II.