Racial Disparities in Uncorrected and Undercorrected Refractive Error in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Virtual Try-On System for Prescription Eyeglasses

Feature Article A Virtual Try-On System for Prescription Eyeglasses Qian Zhang and Yu Guo ■ Nanyang Technological University Pierre-Yves Laffont, Tobias Martin, and Markus Gross ■ ETH Zurich ision-correcting eyeglasses have improved We present a system for virtually trying on pre- the lives of millions of people. Eyeglasses scription eyeglasses. Our system acts as a virtual significantly affect the wearer’s appear- mirror, allowing users to try on a variety of eye- Vance, and the selection of new pairs of eyeglasses is glasses with corrective lenses based on their pre- largely based on how the glasses look when wearers scription (see Figure 2). We use an image sequence try them on. However, an often overlooked fact is of the user without eyeglasses as input, along with that corrective lenses introduce distortion caused the user’s eyeglasses prescription and a 3D model by the refraction effect. As Figure 1 illustrates, the of the desired eyeglasses frame. Our system gen- eyes of a person wearing correc- erates a 3D representation of the corrective lenses tive lenses for nearsightedness mounted into the eyeglasses frame and modifies the Corrective lenses introduce appear smaller compared with video sequence to virtually insert the eyeglasses us- distortion caused by the wearing nonprescription lenses, ing image-based rendering. This approach simulates refraction effect, which whereas the eyes of a person the distortion introduced by the prescription lenses changes the wearer’s wearing lenses for farsightedness and gives users a better idea of how they would look appearance. To give users a appear larger. when wearing the new pair of eyeglasses. -

Intraocular Lenses and Spectacle Correction

MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE INTRAOCULAR LENSES, SPECTACLE CORRECTION AND IRIS PROSTHESIS POLICY NUMBER MP-6.058 Original Issue Date (Created): 6/2/2020 Most Recent Review Date (Revised): 6/9/2020 Effective Date: 2/1/2021 POLICY PRODUCT VARIATIONS DESCRIPTION/BACKGROUND RATIONALE DEFINITIONS BENEFIT VARIATIONS DISCLAIMER CODING INFORMATION REFERENCES POLICY HISTORY I. POLICY Intraocular Lens Implant (IOL) Initial IOL Implant A standard monofocal intraocular lens (IOL) implant is medically necessary when the eye’s natural lens is absent including the following: Following cataract extraction Trauma to the eye which has damaged the lens Congenital cataract Congenital aphakia Lens subluxation/displacement A standard monofocal intraocular lens (IOL) implant is medically necessary for anisometropia of 3 diopters or greater, and uncorrectable vision with the use of glasses or contact lenses. Premium intraocular lens implants including but not limited to the following are not medically necessary for any indication, including aphakia, because each is intended to reduce the need for reading glasses. Presbyopia correcting IOL (e.g., Array® Model SA40, ReZoom™, AcrySof® ReStor®, TECNIS® Multifocal IOL, Tecnis Symfony and Tecnis SymfonyToric, TRULIGN, Toric IO, Crystalens Aspheric Optic™) Astigmatism correcting IOL (e.g., AcrySof IQ Toric IOL (Alcon) and Tecnis Toric Aspheric IOL) Phakic IOL (e.g., ARTISAN®, STAAR Visian ICL™) Replacement IOLs MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE INTRAOCULAR LENSES, SPECTACLE CORRECTION AND IRIS PROSTHESIS POLICY NUMBER -

A Breakthrough in Myopia Control for Your Child

USER GUIDE FOR MiYOSMART MiYOSMART OPTOMETRIC PROTOCOL FOR MiYOSMART MiYOSMART MiYOSMART: A SMART APPROACH TO MYOPIA MiYOSMART The user guide identies what new MiyoSmart wearers should take note of during the adaptation period. To ensure maximized benets of MiyoSmart are experienced, it is recommended to follow the optometric protocol. If you had a way to halt or slow down the progression of myopia, surely you would want to know how. Adaption to new lenses MiyoSmart delivers on this promise and lls a rapidly growing market need. MiyoSmart is an innovative 1ST VISIT 1. It always takes time to get used to your new lenses. The time needed really depends on the individual but wearers can ophthalmic lens for myopia control developed by Hoya Vision Care in cooperation with its research expect about one to two weeks to adapt. collaborator, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU). Engineered specically to correct myopic During the rst visit, all visual functions of the child should be assessed to get a clear overview of the current status. A few 2. During the adaptation time, the wearer should avoid: factors are examined to ascertain if the wearer is suitable for MiyoSmart. refractive error and slow down myopia progression, MiyoSmart comes to market at a time when the 1 It is also essential to know the child and his/her parents' ocular and optical history. incidence of myopia is on the rise. Preliminary investigation will also have to be done, where it is compulsory to conduct the following tests and examinations: An estimated 5 billion Research shows that Intensive sport Operating any Using the new lenses Using them on high people, or activities, e.g. -

Types of Contact Lenses and Their Characteristics1

3 ■ Types of Contact Lenses and Their Characteristics1 The basic categories of contact lenses currently acetate butyrate [CAB], PMMA-silicone, and in use are the original hard (polymethylmethacry- silicone). There are variations within each group, late [PMMA]) lenses, soft hydrogels (hydro- but their respective properties are similar enough xymethylmethacrylate [HEMA] and other mate- to consider them as essentially the same type of rials), and gas-permeable hard lenses (cellulose lenses. HARD PMMA LENSES As discussed in the previous chapter, hard rial and safe for use in the eye. It can be molded PMMA lenses were the first lenses introduced or lathed into lenses with a high degree of preci- onto the market, and corneal PMMA lenses simi- sion. Once made, PMMA lenses can be reworked lar to those currently in use have been available and modified to customize them to an individual’s since the early 1950s. Compared to later types of requirements. The result is a safe lens of excellent lenses, PMMA lenses can be difficult to adapt to, visual properties which very closely conforms to and perhaps as many as half of the people fitted patient requirements. PMMA lenses require min- do not become long-term wearers. Since PMMA imal use of cleaning, soaking, and wetting solu- is not water- or gas-permeable, wearers must rely tions. They may be tinted to reduce excessive light on the “tear pump” action of the eye to provide sensitivity, to make them easier to find when oxygen to the covered portion of the cornea. As dropped, or for appearance reasons. They are the wearer blinks, tear interchange occurs from durable, can be renewed by polishing away mi- outside the lens to beneath it, providing the nec- nor surface scratches, and often last 5 to 7 years essary oxygen. -

Lenses and Optics

PHYS 1400: Physical Science for General Education Laboratory Manual LENSES AND OPTICS INTRODUCTION If you (or your cat) wear glasses or contact lenses, you are already familiar with the science of optics. Whether you realize it or not, you understand the idea of a focal point. You are very aware when an image is out of focus (no glasses) or in focus (put your glasses back on). You even know the difference between a real and a virtual image, although you have probably never said to yourself, “I wish that the real image formed by the lens in my eye was better focused on my retina!” Or may be you have. OBJECTIVES ๏ Identify the differences between concave and convex lenses ๏ Use the lens equation to Steampunk Cat is equipped for any ocular emergency. determine the focal length of a convex lens Convex lenses are converging lenses. ๏ Construct ray diagrams to accurately show how an image is formed Concave lenses are diverging lenses. ๏ Demonstrate the difference between a near– and far–sighted eye, and show how each vision problem can be corrected ACTIVITY 1: CONVERGING AND DIVERGING LENSES ๏ Use the converging and diverging lenses to observe objects around the room. ๏ Try to use both as magnifying glasses to enlarge text. ๏ While observing a single object, move the lens toward and away from your eye. Do this for both types of lens. ๏ Try observing objects using various combinations of lenses: two converging, two diverging, one of each. QUESTIONS 1. Which type of lens can you use to magnify text? What happens to the magnified image as you draw the lens farther from the text? 2. -

Primal Contact Lenses Care Instructions and Waiver Page 1 PRIMAL CONTACTS

PRIMAL CONTACTS - Soft (Hydrophilic) Contact Lenses Eye Care Instructions IMPORTANT: Please read carefully and keep this information for future use. Primal Brand Contacts Lenses are available as corrective and non-corrective lens designs. The Lenses are composed of 62% Polymacon and 38% water a silicone-containing hydrogel. PRIMAL (NON-CORRECTIVE) CONTACT LENSES PARAMETERS Diameter : 14,0 mm to 14,8 mm Base Curve : 8,6 mm to 8,8 mm Power : Plano INDICATIONS (USES) AND WEARING RESTRICTIONS Primal ® Brand Fashion Lenses is indicated for non-corrective use in the colour enhancement of the iris and have no therapeutic effects for daily wear. CONTRAINDICATIONS (REASONS NOT TO USE PRIMAL BRAND CONTACT LENSES) Inflammation or infection in or around the eye or eyelids. Any eye disease, injury, or abnormality that affects the cornea, conjunctiva, or eyelids. Any previously diagnosed condition that makes contact lens wear uncomfortable. Any systemic disease that may affect the eye or be exaggerated by wearing contact lenses. Allergic reactions of ocular surfaces of the eye (adnexa) that may be induced or exaggerated by wearing contact lenses or use of contact lens solutions. Allergy to any ingredient, such as mercury or Thimerosal, in a solution which is to be used to care for your contact lenses. Severe dry eye. Any active corneal infection (bacterial, fungal, protozoal or viral). Not to be used if you are unable to follow the lens care regimen or unable to obtain assistance to do so. POTENTIAL ADVERSE SIDE EFFECTS FROM WEARING PRIMAL BRAND CONTACT LENSES Stinging, burning, itching (irritation), pain, tearing or other eye discomfort or sensation of foreign object in the eye. -

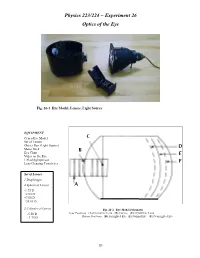

Physics 223/224 ~ Experiment 26 Optics of the Eye

Physics 223/224 ~ Experiment 26 Optics of the Eye Fig. 26-1 Eye Model, Lenses, Light Source EQUIPMENT Cenco Eye Model Set of Lenses Object Box (Light Source) Meter Stick Eye Chart Video on the Eye 1 Flashlight/person Lens Cleaning Towelettes Set of Lenses 1 Diaphragm 4 Spherical Lenses -1.75 D +2.00 D +7.00 D +20.00 D 2 Cylindrical Lenses Fig. 26-2 Eye Model Schematic -5.50 D Lens Positions: (A) Corrective Lens (B) Cornea (C) Crystalline Lens +1.75 D Retina Positions: (D) Farsighted Eye (E) Normal Eye (F) Nearsighted Eye 221 Physics 223/224 ~ Experiment 26 Optics of the Eye Advance Reading Accommodation refers to the ability of the crystalline lens to contract/relax to make minor adjustments in focusing an image. Text: Vision, myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, cornea, As people age, this ability is reduced – presbyopia. retina, blind spot. The power of a lens is referenced when discussing corrective Objective lenses: The objective of this experiment is to study the optical properties of the human eye using an eye model. Eq. 26-1. Theory The human eye can be thought of as a positive lens Lenses can be converging (positive) or diverging (negative). system that focuses a real image on a light-sensitive The power of a lens is also, of course, positive or negative. The surface, the retina. Most of the refraction of light -1 unit is diopter, D, or m . occurs at the cornea-air interface (at the surface of the eye), since this interface has the greatest change in the Visual pigments are found in the rods and cones of the retina. -

Myopia Control in Children Through Refractive Therapy Gas Permeable Contact Lenses: Is It for Real?

PERSPECTIVE Myopia Control in Children through Refractive Therapy Gas Permeable Contact Lenses: Is it for Real? BRUCE H. KOFFLER AND JAMES J. SEARS PURPOSE: To compare the safety and efficacy of ortho- successful of these treatments was the use of antimuscarinic keratology as a nonsurgical treatment for myopia in chil- medications, such as atropine, pirenzepine gel, and cyclo- dren with alternate methods, such as soft contact lenses, pentolate. However, this approach led to adverse side rigid gas permeable lenses, and spectacles, throughout effects of light sensitivity and blurred vision. The drugs multiple studies. required were not readily available to the patient, making 4 DESIGN: Perspective with literature review. the treatment costly and impractical. Orthokeratology, METHODS: Analysis of recent studies to determine the or the more current technique of corneal reshaping or safety and effectiveness of orthokeratology versus soft refractive therapy, is a more effective strategy for addressing contact lenses, rigid gas permeable lenses, and spectacles myopia up to À5 diopters (D) and astigmatism up to 1.5 D. in children. It alters how light is refracted by reshaping the cornea into RESULTS: In all of the studies reviewed, the use of a flatter surface while slowing axial length elongation in orthokeratology lenses proved to reduce myopia, to younger patients. It is reversible, so if the patient is improve visual acuity, and, with the exception of the unhappy with the treatment, they can simply discontinue SMART study, to reduce the rate of axial elongation. wearing the lenses. Orthokeratology has been shown to be as effective as other methods in treating myopia and to be more effective at treating axial elongation. -

The Eye & Corrective Lenses

Phys 102 – Lecture 20 The eye & corrective lenses 1 Today we will... • Apply concepts from ray optics & lenses Simple optical instruments – the camera & the eye • Learn about the human eye Accommodation Myopia, hyperopia, and corrective lenses • Learn about perception of size Angular size Magnifying glass & angular magnification Phys. 102, Lecture 19, Slide 2 The Camera Cameras are one of simplest optical instruments, produce real image onto sensor Pinhole camera (“camera obscura”) Modern camera Pinhole Imaging lens 11 1 += DEMO ddo i f lens Not a true imaging system. Each point from True imaging system. Each point from object creates a circle of light on screen. object has a corresponding point on screen. Phys. 102, Lecture 20, Slide 3 Evolution of the eye The eye is like a camera Pinhole eye Complex eye Nautilus Octopus Phys. 102, Lecture 20, Slide 4 Anatomy of the human eye As in a camera, eye lens creates image of object onto retina Ciliary muscles Vitreous Part of eye n Cornea fluid Cornea 1.351 Lens 1.437 Pupil Vitreous fluid 1.333 Retina Lens Iris Optic nerve DEMO Pupil controls amount of light – diameter typically 2-8 mm Retina has ~125 million photoreceptor cells (rods & cones) Phys. 102, Lecture 20, Slide 5 ACT: Anatomy of the Eye Which part of the eye is responsible for most of the bending of light? Vitreous Cornea fluid Part of eye n Retina Cornea 1.351 Lens 1.437 Laser eye surgery Lens Vitreous fluid 1.333 changes cornea! A. Lens B. Cornea C. Retina D. Vitreous fluid Shape and index of refraction mismatch determine how much light bends: Lens and cornea have similar shape and n n 1.44 n 1.35 nlens 1.44 lens = ≈1.06 cornea = ≈1.35 = ≈1.08 n 1.33 ncornea 1.35 nair 1 vitreous Most of bending occurs at air-cornea interface Phys. -

Lab 12 Optics of The

Optics of the Eye Goal: To investigate some of the principles of the human eye. Lab Preparation We see objects because light bounces off of them and into our eyes. For normal vision light enters our eye and is focused on our retina. This forms an image of the object, much like your convex lenses formed images on screens in the previous labs. Some of the basic relationships that will be used in this lab are: a. Power of a lens (in diopters): � = ! where f is the focal length in meters. ! b. Thin lens equation: ! = ! + ! ! !! !! c. Magnification equation: � = !! = − !! !! !! During this lab we will investigate accommodation, normal vision, and some defects of the eye using the eye model provided. Equipment The Human Eye Model consists of a sealed plastic tank shaped roughly like a horizontal cross section of an eyeball. A permanently mounted convex lens on the front of the eye model acts as the cornea. The tank is filled with water, which models the aqueous and vitreous humors. The lens of the eye is modeled by a changeable lends behind the cornea. A moveable screen at the back of the model represents the retina. A picture of the eye model is below. Tops View Procedure I. Introduction to the Eye Model Your eye model consists of a cornea and the following: *Slots 1 and 2 are outside the cornea and will be used for vision correction. *Slots A, B, and SEPTUM are just inside the cornea and are used to simulate the lens of the eye. *Slots FAR, NORMAL, and NEAR are back where the retina screen is placed. -

Section 2 Vision Care Services

Utah Medicaid Provider Manual Vision Care Services Division of Medicaid and Health Financing Updated April 2019 Section 2 Vision Care Services Table of Contents 1 General Information ........................................................................................................................................ 2 1-1 General Policy ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1-2 Fee-For-Service or Managed Care .......................................................................................................... 2 1-3 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Provider Participation Requirements .............................................................................................................. 3 2-1 Provider Enrollment ................................................................................................................................ 3 3 Member Eligibility .......................................................................................................................................... 3 4 Program Coverage ........................................................................................................................................... 4 4-1 Covered Services .................................................................................................................................... -

Management of Extended-Wear Contact Lenses in Infant Rhesus Monkeys

Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 1988, 20 (I), 11-17 Management of extended-wear contact lenses in infant rhesus monkeys ALCIDES FERNANDES, MARGARETE TIGGES, JOHANNES TIGGES, J. ALLEN GAMMON, and CHARLES CHANDLER Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia Infant rhesus monkeys were fitted with extended-wear contact lenses (EWCLs) to correct sur gically induced aphakia. The protocol that produced the most favorable experimental outcome, including goodlens-wear compliance, involved: (1) custom-made EWCLs with parameters adjusted for each animal, (2) selection for study of neonates who seemed to tolerate EWCLs most natur ally, (3)individual housing of monkeys, (4)lens check at 2-h intervals around the clock by trained personnel, (5) a large inventory of EWCLs for each animal, (6) periodic ophthalmologic examina tions, and (7)darkroom housing of monkeys during treatment oflens-wear-related incidents. The EWCL is a new tool for studies of the visual system and is a useful complement to existing ex perimental techniques. The visual system of infant rhesus monkeys has been they provide a wide range of possibilities for manipulat studied extensively to determine the effects of visual ex ing the visual input under various deprivation conditions. perience on the development ofnormal visual functions. For example, lenses can be designed to produce focused In particular, experiments using monocular deprivation images on the retina of objects at known distances, near have proven the importance of equal patterned inputs to to the monkey or far from it. Lenses can be dyed black both eyes for the development of binocular vision. For and used as occluders to reduce stimulation of the retina.