Beyond Singapore Girl Anderson, B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

2009, and Electronic Visits Rose to About 6 Million, an Increase of 12 Percent from the Previous Year

Message from Chairman and Chief Executive The year in review was a period of significant achievements for the National Library Board (NLB). Book and audiovisual loans registered a new record of close to 31 million, about 11 percent increase from FY2008/2009, and electronic visits rose to about 6 million, an increase of 12 percent from the previous year. The number of electronic retrievals last year was about 48 million, a tremendous 72 percent more than the previous year. The record levels of library use demonstrated the enduring value of our libraries to lifelong learning. Over the past year, while grappling with the challenges of an economic downturn, Singaporeans continued to turn to our libraries as trusted sources of knowledge and information that would help them gain new insights, seize opportunities and achieve their aspirations. On another level, the rising importance of our libraries is heartening proof that our progress towards Library 2010 (L2010) has had a meaningful impact on the lives of Singaporeans in this digital age. L2010 is the strategic roadmap to build a seamless 24/7 library system leveraging diverse digital and physical delivery channels. In the past year, we continued to enhance our collections and expand our patrons’ access to both traditional and digital content. At the same time, we strived to meet the diverse needs of our patrons with a broad range of programmes and service initiatives. Developing and Ensuring Access to Our Collections Good collections and access to them are fundamental to the quality of knowledge that our libraries offer. In the year in review, we continued to enhance and refresh our print, digital and documentary materials through donations, acquisitions and digitisation. -

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore

Institutionalized Leadership: Resilient Hegemonic Party Autocracy in Singapore By Netina Tan PhD Candidate Political Science Department University of British Columbia Paper prepared for presentation at CPSA Conference, 28 May 2009 Ottawa, Ontario Work- in-progress, please do not cite without author’s permission. All comments welcomed, please contact author at [email protected] Abstract In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party autocracy is puzzling. The People’s Action Party (PAP) has defied the “third wave”, withstood economic crises and ruled uninterrupted for more than five decades. Will the PAP remain a deviant case and survive the passing of its founding leader, Lee Kuan Yew? Building on an emerging scholarship on electoral authoritarianism and the concept of institutionalization, this paper argues that the resilience of hegemonic party autocracy depends more on institutions than coercion, charisma or ideological commitment. Institutionalized parties in electoral autocracies have a greater chance of survival, just like those in electoral democracies. With an institutionalized leadership succession system to ensure self-renewal and elite cohesion, this paper contends that PAP will continue to rule Singapore in the post-Lee era. 2 “All parties must institutionalize to a certain extent in order to survive” Angelo Panebianco (1988, 54) Introduction In the age of democracy, the resilience of Singapore’s hegemonic party regime1 is puzzling (Haas 1999). A small island with less than 4.6 million population, Singapore is the wealthiest non-oil producing country in the world that is not a democracy.2 Despite its affluence and ideal socio- economic prerequisites for democracy, the country has been under the rule of one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP) for the last five decades. -

Women in the Philippine Workforce

CONTENTS 5 Preface 7 Authors MAIN TOPICS 9 Work-Life Balance: The Philippine Experience in Male and Female Roles and Leadership Regina M. Hechanova 25 Rural Women’s Participation in Politics in Village-level Elections in China Liu Lige 37 Status of Women in Singapore and Trends in Southeast Asia Braema Mathiaparanam 51 Gender and Islam in Indonesia (Challenges and Solution) Zaitunah Subhan 57 Civil Society Movement on Sexuality in Thailand: A Challenge to State Institutions Varaporn Chamsanit DOCUMENTS 67 Joint Statement of the ASEAN High-Level Meeting on Good Practices in CEDAW Reporting and Follow-up 3 WEB LINKS 69 Informative websites on Europe and Southeast Asia ABSTRACTS 73 4 PREFACE conomic progress and political care giver. Similarly, conservative Eliberalisation have contributed religious interpretations undermine greatly to tackling the challenges of reform of outdated concepts of the role poverty and inequality in Asia. Creating and status of women in Asian societies. equal opportunities and ensuring equal The articles presented in this edition treatment for women is a key concern for of Panorama are testimony to the civil society groups and grassroots leaders multitude of challenges faced by women across the region. Undoubtedly, in most across Asia in the struggle to create parts of Asia, women today enjoy greater gender equality. They range from freedoms than their mothers did before addressing a shift in traditional gender them including improved access to roles derived from advancing healthcare, enhanced career opportunities, modernisation and globalisation to the and increased participation in political need to identify ways and means to decision-making. Nonetheless, key support women in their rightful quest challenges persistently remain. -

Changing Constructions of the Family in Singapore

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities October 1998 The ‘Graduate Woman’ Phenomenon: Changing Constructions of the Family in Singapore Lenore T. Lyons-Lee University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Lyons-Lee, Lenore T., The ‘Graduate Woman’ Phenomenon: Changing Constructions of the Family in Singapore 1998. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/96 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The ‘Graduate Woman” Phenomenon: Changing Constructions of the Family in Singapore Lenore Lyons -Lee Introduction In recent years the Singapore state, as part of its broader population planning policy, has focused attention on encouraging graduate men a nd women to marry and have children at a younger age. These policies have been promoted through a series of well -publicised advertising campaigns in the television and print media. Tertiary educated women have been constructed as ‘problematic’ within thi s discourse of state -directed social change because they are marrying later, having fewer children, and on occassion foregoing marriage altogether. This paper examines the ways such women understand the current marrige debate, and the reasons they give fo r their life choices. I will argue that contrary to popular media and state views, such women have not rejected marriage but rather traditional constructions of gender roles within the family. -

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of SINGAPORE's INDUSTRIALIZATION: National State and International Capital

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF SINGAPORE'S INDUSTRIALIZATION: National State and International Capital The Political Economy of Singapore's Industrialization: National State and International Capital GARRYRODAN Leclurer in Politics Murdoch University, Australia Pal grave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-19925-9 978-1-349-19923-5 (eBook) DOl 10.1007/978-1-349-19923-5 © Garry Rodan, 1989 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1989 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1989 ISBN 978-0-312-02412-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rodan, Garry, 1955- The political economy of Singapore's industrialization: national state and international capital/Garry Rodan. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-312-02412-3:$35.00 (est.) 1. Industry and state-Singapore. I. Title. HD3616.S423R64 1989 338.9595'7--dcI9 88-18174 CIP Dedicated to my parents, Betty and Ken Contents Acknowledgements viii Abbreviations ix List of Tables xi Prefatory Notes xii Preface xiii 1 Theoretical Introduction 1 2 Pre-Industrial Singapore: General Structural Developments up until 1959 31 3 The Political Pre-Conditions 50 4 Export-Oriented Manufacturing 85 5 Second Industrial Revolution 142 6 Singapore's Future as a NIC 189 7 Conclusions: Singapore and the New International 207 Division of Labour Notes 216 Bibliography 244 Index 258 VII Acknowledgements In their different ways, and to varying degrees, numerous people have contributed to the realisation of this book. The detailed critical comments and encouragement of my colleagues Richard Robinson and Richard Higgott have, however, made a special contribution. -

Singapore: an Entrepreneurial Entrepôt?

CASE STUDY Singapore: An Entrepreneurial Entrepôt? June 2015 Dr. Phil Budden MIT Senior Lecturer MIT REAP Diplomatic Advisor Prof. Fiona Murray MIT Sloan Associate Dean for Innovation Co-Director, MIT Innovation Initiative Singapore: An Entrepreneurial Entrepôt? Fiona Murray MIT Sloan Associate Dean for Innovation, Co-Director MIT Innovation Institute Phil Budden MIT Senior Lecturer, MIT REAP Diplomatic Advisor Prepared for MIT REAP in collaboration with the MIT Innovation Initiative Lab for Innovation Science and Policy June 28, 2015 DRAFT NOT FOR CIRCULATION "Singaporeans sense correctly that the country is at a turning point…We will find a new way to thrive in this environment…We must now make a strategic shift in our approach to nation-building. Our new strategic direction will take us down a different road from the one that has brought us here so far. There is no turning back. I believe this is the right thing to do given the changes in Singapore, given the major shifts in the world.” - Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, 20131 Nine years after accepting his role as Singapore’s Prime Minister (PM), Lee Hsien Loong spoke these words to an audience at the National Day Rally of 2013 at the Institute of Technical Education’s (ITE) College Central, commemorating his country’s 48th year of independence. PM Lee Hsien succeeded his predecessor Goh Chok Tong in 2004, a time when his nation was reconsidering its economic strategy in a world still recovering from the financial crises of the late 1990’s and the recession of 2001. Nearly a decade later, PM Lee Hsien was still faced with similar challenges: ensuring continued growth for a small nation in an increasingly competitive global economy. -

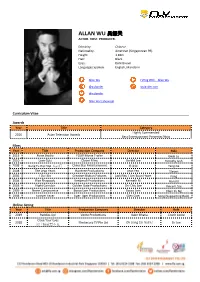

Allan Wu 吴振天 Actor

ALLAN WU 吴振天 ACTOR. HOST. PRODUCER. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: American (Singaporean PR) Height: 1.83m Hair: Black Eyes: Dark Brown Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin Allan Wu FLYing With... Allan Wu @wulander wulander.com @wulander Allan Wu's Showreel Curriculum Vitae Awards Year Title Category Highly Commended 2016 Asian Television Awards Best Entertainment Presenter/Host Films Year Title Production Company Director Role 2015 Poise Studio FOUR Movie Trailer Gwai Lo 2010 Love Cuts Clover Films Gerald Lee Timothy Goh 2008 Kung Fu Hip Hop 精武门 China Star Entertainment 傅华阳 Tang Ge 2008 The Leap Years Raintree Productions Jean Yeo Steven 2005 I Do I Do Creative Motion Pictures Jack Neo / Lim Boon Hwee Feng 2004 Rice Rhapsody Kenberoli Productions Kenneth Bi Ronald 2003 Night Corridor Golden Gate Productions Chi-Chiu Lee Vincent Sze 1999 Never Compromise Bosco Lam Productions Bosco Lam Chun Yu Ng 1998 Forever Fever Tiger Tiger Productions Glen Goei Seng (Supporting Role) Online Acting Year Title Production Company Director Role 2019 Paddles Up! Verite Productions Kabir Bhatia Coach Leslie Close Your Eyes 2018 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Oh Liang Cai 胡凉财 Dr Joe 闭上眼就看不见 Television Actor Year Title Production Company Director Role 2019 CLIF 5 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Oh Liang Cai Alexis 2018 Divided 分裂 Mediacorp TV Pte Ltd Lee Thean-jeen Inspector Wu Wenjie 2014 Mata Mata Season 2 MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd Alan Leong 2014 First Gear House Films Lead 2006 House Of Joy Mediacorp Studios Pte Ltd 罗温温 Zheng Sanji 2006 Xing Jing Er Ren Zhu Mediacorp -

Parliament Sitting Date: 17 Aug 1999 ISSUES RAISED by PRESIDENT

Parliament Sitting Date: 17 Aug 1999 ISSUES RAISED BY PRESIDENT ONG TENG CHEONG AT HIS PRESS CONFERENCE ON 16TH JULY 1999 (Parliamentary Q&As) Mr Jeyaretnam: May I ask the Prime Minister a question or two? I understood him to say that the Cabinet would have been happier if the President had decided to seek re-election. But the Cabinet was concerned whether he was medically capable. But the President had said in his statement that his doctors had given him a clean bill, that his cancer was in complete remission and the President clearly indicated that his health would not stand in the way of his becoming President. May I ask the Prime Minister to explain to this House on what basis or information did the Cabinet conclude that he would not be capable of discharging his duties? Mr Goh Chok Tong: Mr Speaker, Sir, yes, the President had told the public at his press conference regarding his present health situation. But the Cabinet had two medical reports, one from the President's doctor in the United States, Dr Saul Rosenberg, and the other from his physician in Singapore. We studied the reports and it was quite clear from the reports that if you should focus or project the President's health condition into the future, there was a very strong likelihood that he would not be able to perform his duties normally. In a sense, it is like looking at a glass of water, whether it is one-third full or two-thirds empty. The Cabinet had to take the advice of the doctor and take a very careful view of what the President's future condition would be like. -

—From This Land We Are Made“: Christianity, Nationhood, and the Negotiation of Identity in Singapore Women's Writing Olivi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS “FROM THIS LAND WE ARE MADE”: CHRISTIANITY, NATIONHOOD, AND THE NEGOTIATION OF IDENTITY IN SINGAPORE WOMEN’S WRITING OLIVIA GARCIA-MCKEAN (A.B. English Literature (Magna Cum Laude), Harvard College) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER BY RESEARCH IN ENGLISH LITERATURE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND LANGUAGE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2005 - ii - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A remarkable trip to Cambodia opened my eyes to the diversity of Southeast Asia and first inspired the idea to attend NUS. My parents—although they were surprised and most likely more than a little apprehensive—were extremely supportive of my dream. Coming to Singapore was the best decision I have ever made. Living here—taking in the morning pleasures of teh tarik and kaya toast, running at sunset around the reservoir, and watching the lightning storms from above the clouds—has given me the opportunity to grow, to reflect, and to dream big dreams. I would like to thank Dr. Robbie Goh for initially corresponding with me via email and helping me decide on a topic. Over the course of the next two years as my supervisor, Dr. Goh has been unbelievably supportive and empathetic. His feedback rescued my thesis when it seemed ready to sink. Thank you for taking the time to reach out to me. I would also like to express gratitude for the many friends I have made at NUS. Unfortunately the transient nature of this institution and city has made saying goodbye a frequent event.