Ho Yean Theng Jill V Public Prosecutor [2003]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rule of Law and Urban Development

The Rule of Law and Urban Development The transformation of Singapore from a struggling, poor country into one of the most affluent nations in the world—within a single generation—has often been touted as an “economic miracle”. The vision and pragmatism shown by its leaders has been key, as has its STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS notable political stability. What has been less celebrated, however, while being no less critical to Singapore’s urban development, is the country’s application of the rule of law. The rule of law has been fundamental to Singapore’s success. The Rule of Law and Urban Development gives an overview of the role played by the rule of law in Singapore’s urban development over the past 54 years since independence. It covers the key principles that characterise Singapore’s application of the rule of law, and reveals deep insights from several of the country’s eminent urban pioneers, leaders and experts. It also looks at what ongoing and future The Rule of Law and Urban Development The Rule of Law developments may mean for the rule of law in Singapore. The Rule of Law “ Singapore is a nation which is based wholly on the Rule of Law. It is clear and practical laws and the effective observance and enforcement and Urban Development of these laws which provide the foundation for our economic and social development. It is the certainty which an environment based on the Rule of Law generates which gives our people, as well as many MNCs and other foreign investors, the confidence to invest in our physical, industrial as well as social infrastructure. -

The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore

Damien Cheong ____________________________________________________________ Selling Security: The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore DAMIEN CHEONG Abstract The Internal Security Act (ISA) of Singapore has been transformed from a se- curity law into an effective political instrument of the Singapore government. Although the government's use of the ISA for political purposes elicited negative reactions from the public, it was not prepared to abolish, or make amendments to the Act. In the wake of September 11 and the international campaign against terrorism, the opportunity to (re)legitimize the government's use of the ISA emerged. This paper argues that despite the ISA's seeming importance in the fight against terrorism, the absence of explicit definitions of national security threats, either in the Act itself, or in accompanying legislation, renders the ISA susceptible to political misuse. Keywords: Internal Security Act, War on Terrorism. People's Action Party, Jemaah Islamiyah. Introduction In 2001/2002, the Singapore government arrested and detained several Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) operatives under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for engaging in terrorist activities. It was alleged that the detained operatives were planning to attack local and foreign targets in Singa- pore. The arrests outraged human rights groups, as the operation was reminiscent of the government's crackdown on several alleged Marxist conspirators in1987. Human rights advocates were concerned that the current detainees would be dissuaded from seeking legal counsel and subjected to ill treatment during their period of incarceration (Tang 1989: 4-7; Frank et al. 1991: 5-99). Despite these protests, many Singaporeans expressed their strong support for the government's actions. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

NIE News September 2013.Pdf

An Institute of Distinction September 2013 No.85 ISSN 0218-4427 GROWING EXCELLENCE 3 CORPORATE DEVELOPMENT Latest campus news 14 SPECIAL FEATURE Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony July 2013 RESEARCH 20 Highlights on experts and projects A member of An Institute of INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE of LEADING EDUCATION INSTITUTES Editorial Team: Associate Professor Jason Tan Eng Thye, Patricia Campbell, Monica Khoo, Julian Low NIE News is published quarterly by the Public International and Alumni Relations CONTENTS Department, National Institute of Education, CORPORATE DEVELOPMENT Staff Welfare Recreation Fund Singapore. Malay Values and Graces Camp 3 Committee Activities 19 Design by Graphic Masters & Advertising Asian Regional Association for Pte Ltd Home Economics Congress 2013 4 SPECIAL FEATURE NIE News is also available at: www.nie.edu.sg/nienews Learning Week for Staff 4 Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony July 2013 14 - 15 If you prefer to receive online versions English Language and Literature of NIE News, and/or wish to update your particulars please inform: Postgraduate Conference 2013 5 RESEARCH Arts Education Talk 5 The Editorial Team, NIE News C J Koh Professorial Lecture – 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616 NIE Art Collection Launch 6 Professor Linda Darling-Hammond 20 Tel: +65 6790 3034 Visual and Performing Arts Farewell Professor Fax: +65 6896 8874 Academic Group hosts A. Lin Goodwin 21 Email: [email protected] Hong Kong Institute of LSL academics and staff clinch Education visitors 7 more awards 22 Prominent Visitors 8 - 9 9th Asia-Pacific -

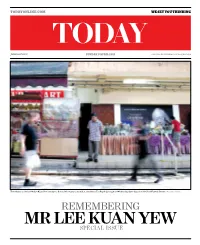

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

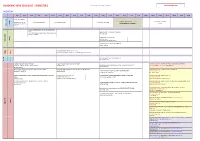

Class Timetable for Lecture/Seminar

ACADEMIC YEAR 2019/2020 - SEMESTER 2 (1920) Page 1: Semester 2 AY19-20 Timetable_(ver 9 January 2020) Version 9 January 2020 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE LC1003 LAW OF CONTRACT LECTURE {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL BURTON ONG, DORA NEO, SANDRA BOOYSEN, KELRY LOI, {Yale 2} ELEANOR WONG, LIM LEI TAN ZHONG XING, ALLEN SNG, MINDY CHEN-WISHART Weekly THENG, SONITA JEYAPATHY, RUBY LEE YEAR 1 CORE 1 YEAR LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC2007 CONSTITUTIONAL & ADMIN LAW LECTURE {Yale LC2006A, B & C EQUITY & TRUSTS SECTIONS ((A) B) & (C) {Yale 4} 3} LC2006D, E & F EQUITY & TRUSTS SECTIONS (D), (E) & (F) RACHEL LEOW (A); KELRY LOI (B); TAN YOCK LIN (C) THIO LI-ANN, SWATI JHAVERI, KEVIN TAN, DIAN SHAH, RACHEL LEOW (D); TAN YOCK LIN (E); TAN WEI MENG (F) CORE YEAR 2 Weekly JACLYN NEO, MARCUS TEO LC6378 Doctoral Workshop DAMIAN CHALMERS D CORE Weekly G LL4044V/LL5044V/LL6044V MEDIATION LL4019V/LL5019/ LL6019V CREDIT & SECURITY LL4063V/LL5063V/LL6063V BUSINESS & FINANCE FOR LAWYERS LL4371/LL5371/LL6371 CHARITY LAW TODAY INTENSIVE [WEEK 1-3] JOEL LEE, MARCUS LIM DORA NEO STEPHEN PHUA/JAMES LEONG MATTHEW HARDING LL4372/LL5372/LL6372 INTERNATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW INTENSIVE LL4402/LL5402/LL6402 CORPORATE INSOLVENCY LL4024V/LL5024V/LL6024V INDONESIAN LAW LL4205V/LL5205V/LL6205V/LLD5205V MARITIME CONFLICT OF LAWS [WEEK 1-3] WEE MENG SENG GARY -

Parliament Sitting Date: 17 Aug 1999 ISSUES RAISED by PRESIDENT

Parliament Sitting Date: 17 Aug 1999 ISSUES RAISED BY PRESIDENT ONG TENG CHEONG AT HIS PRESS CONFERENCE ON 16TH JULY 1999 (Parliamentary Q&As) Mr Jeyaretnam: May I ask the Prime Minister a question or two? I understood him to say that the Cabinet would have been happier if the President had decided to seek re-election. But the Cabinet was concerned whether he was medically capable. But the President had said in his statement that his doctors had given him a clean bill, that his cancer was in complete remission and the President clearly indicated that his health would not stand in the way of his becoming President. May I ask the Prime Minister to explain to this House on what basis or information did the Cabinet conclude that he would not be capable of discharging his duties? Mr Goh Chok Tong: Mr Speaker, Sir, yes, the President had told the public at his press conference regarding his present health situation. But the Cabinet had two medical reports, one from the President's doctor in the United States, Dr Saul Rosenberg, and the other from his physician in Singapore. We studied the reports and it was quite clear from the reports that if you should focus or project the President's health condition into the future, there was a very strong likelihood that he would not be able to perform his duties normally. In a sense, it is like looking at a glass of water, whether it is one-third full or two-thirds empty. The Cabinet had to take the advice of the doctor and take a very careful view of what the President's future condition would be like. -

Competing Narratives and Discourses of the Rule of Law in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2012] 298–330 SHALL THE TWAIN NEVER MEET? COMPETING NARRATIVES AND DISCOURSES OF THE RULE OF LAW IN SINGAPORE Jack Tsen-Ta Lee∗ This article aims to assess the role played by the rule of law in discourse by critics of the Singapore Government’s policies and in the Government’s responses to such criticisms. It argues that in the past the two narratives clashed over conceptions of the rule of law, but there is now evidence of convergence of thinking as regards the need to protect human rights, though not necessarily as to how the balance between rights and other public interests should be struck. The article also examines why the rule of law must be regarded as a constitutional doctrine in Singapore, the legal implications of this fact, and how useful the doctrine is in fostering greater solicitude for human rights. Singapore is lauded for having a legal system that is, on the whole, regarded as one of the best in the world,1 and yet the Government is often vilified for breaching human rights and the rule of law. This is not a paradox—the nation ranks highly in surveys examining the effectiveness of its legal system in the context of economic compet- itiveness, but tends to score less well when it comes to protection of fundamental ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, School of Law, Singapore Management University. I wish to thank Sui Yi Siong for his able research assistance. 1 See e.g., Lydia Lim, “S’pore Submits Human Rights Report to UN” The Straits Times (26 February 2011): On economic, social and cultural rights, the report [by the Government for Singapore’s Universal Periodic Review] lays out Singapore’s approach and achievements, and cites glowing reviews by leading global bodies. -

Institute O F Southeast Asian Studies

ISEAS Annual Report 2000–01 ISEAS Annual Report Recycled paper Annual Report 2000–01 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Road Singapore 119614 Telephone: 7780955 Facsimile: 7781735 ISEAS Home Page: http://www.iseas.edu.sg THE INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES WAS ESTABLISHED AS AN AUTONOMOUS ORGANIZATION IN 1968. IT IS A REGIONAL RESEARCH CENTRE FOR SCHOLARS AND OTHER SPECIALISTS CONCERNED WITH MODERN SOUTHEAST ASIA, PARTICULARLY THE MANY-FACETED ISSUES AND CHALLENGES OF STABILITY AND SECURITY, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, AND POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHANGE CONTENTS 1EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4MISSION STATEMENT 5ORGANIZATIONAL CHART 6ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE 10 RESEARCH PROGRAMMES AND ACTIVITIES 26 PUBLICATIONS UNIT 30 LIBRARY 37 CENTRAL ADMINISTRATION AND COMPUTER UNIT 39 APPENDICES ICOMMITTEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES II RESEARCH STAFF III NON-RESEARCH PROFESSIONAL STAFF IV STAFF RESEARCH AND PUBLICATIONS VVISITING RESEARCHERS AND AFFILIATES VI FELLOWSHIP AND SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENTS VII LIST OF PUBLIC LECTURES, CONFERENCES, AND SEMINARS VIII LIST OF ISEAS’ NEW PUBLICATIONS, 2000–01 IX DONATIONS, GRANTS, CONTRIBUTIONS, AND REGISTRATION FEES RECEIVED AUDITORS’ REPORT (SEPARATE SUPPLEMENT) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ISEAS was established in 1968 as a regional research institute to promote scholarship, research, analysis, and dialogue on the region’s multi-faceted issues, challenges and problems of stability and security, economic development, and political, social and cultural changes. To this end, the Institute’s multi-disciplinary activities encompass research and publications; public lectures, conferences, seminars and workshops; and training and briefings. The core geographical focus of the Institute remains that of Southeast Asia and ASEAN. Within Southeast Asia, the focus has shifted increasingly to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. -

SEMESTER 2 Page 1: Semester 2 AY1617 Timetable Version 2 November 2016

ACADEMIC YEAR 2016/2017 - SEMESTER 2 Page 1: Semester 2 AY1617 Timetable Version 2 November 2016 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE {Yale 1} LC2009 PRO BONO SERVICE {Yale 1} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL ELEANOR WONG, LIM LEI LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL THENG, SONITA JEYAPATHY, Workshop begins in Semester 2 {Yale 1} Weekly RUBY LEE YEAR 1CORE LC2007 CONSTITUTIONAL & ADMIN LAW LECTURE {Yale 2} LC2006A EQUITY & TRUSTS (A) SEMINAR THIO LI-ANN, SWATI JHAVERI, LYNETTE CHUA, KEVIN TAN, TAN YOCK LIN TAN HSIEN-LI TERESA LC2006 B EQUITY & TRUSTS (B) LECTURE {Yale 3} Weekly NICOLE ROUGHAN, BARRY CROWN YEAR 2CORE LC2006C EQUITY & TRUSTS (C) SEMINAR JAMES PENNER LC3001B EVIDENCE (B) LECTURE {Yale 3} UPPER HO HOCK LAI, CHIN TET YUNG, JEFFREY PINSLER, KENNETH KHOO Weekly YR CORE LC5405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (A) NG-LOY WEE LOON Weekly GD CORE GD LL4054V/LL5054V/LL6054V/LLD5054V LL4407/LL5407/LL6407 LAW OF INSURANCE LL4219/LL5219/LL6219 THE TRIAL OF JESUS IN WESTERN LEGAL THOUGHT DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL SALE OF GOODS YEO HWEE YING LL4405A/LL5405A/LC5405A/LL6405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A INTENSIVE [WEEK 1; 9 Jan 2017] JOSEPH WEILER NG-LOY WEE LOON MICHAEL BRIDGE LL4074V/LL5074V/LL6074V MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS (M&A) LL4195V/LL5195V/LL6195V INT'L ECONOMIC LAW & RELATIONS LL4300/LL5300/LL6300 COPYRIGHT IN THE INTERNET AGE UMAKANTH VAROTTIL WANG JIANGYU LL4071V/LL5071V/LL6071V GLOBAL -

The Effects of the Cla 1956 on Judicial

THE EFFECTS OF THE CLA 1956 ON JUDICIAL DISCRETION, QUANTUM OF DAMAGES AND INTEREST ON DAMAGES IN PERSONAL INJURY AND FATAL ACCIDENT CLAIMS ARISING OUT OF MOTOR VEHICLE ACCIDENTS : A CRITICAL APPRAISAL NAZLI BINTI MAHDZIR THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LAW INSTITUTE OF GRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2014 i UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate : Nazli Binti Mahdzir Registration No : LHA 090003 Name of Degree : Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis : The Effects of the CLA 1956 on Judicial Discretion, Quantum of Damages and Interest on Damages in Personal Injury and Fatal Accident Claims Arising Out of Motor Vehicle Accidents : A Critical Appraisal Field of Study : Insurance and Personal Injury Law I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: 1. I am the sole author / writer of this Work; 2. This Work is original; 3. Any use of Work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt of extract form, or reference to or production of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly or sufficiently and the title of the work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; 4. I do have actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this Work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; 5. I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (UM), who henceforth shall be the owner of the copyright on this Work and that any production of use in any form or by any mean whatsoever is prohibited without written consent of UM first had and obtained; i 6. -

Singapore's Early Sikh Pioneers

SINGAPORE’S EARLY SIKH PIONEERS Origins, Settlement, Contributions and Institutions RISHPAL SINGH SIDHU CENTRAL SIKH GURDWARA BOARD SINGAPORE Singapore’s Early Sikh Pioneers: Origins, Settlement, Contributions and Institutions Rishpal Singh Sidhu Compiler & Editor CENTRAL SIKH GURDWARA BOARD SINGAPORE Front Cover Photo: A collage of the seven Sikh Gurdwaras and Singapore Khalsa Association in Singapore Back Cover Photo: A collage of some of Singapore’s Early Sikh Pioneers Copyright, Central Sikh Gurdwara Board, Singapore, 2017 ISBN: 978-981-09-4437-7 Printed by: Khalsa Printers Pte Ltd, Singapore DEDICATION Dedicated to Sikh youth in Singapore in the fervent belief they will build on the achievements and contributions of their forebears for a better and brighter tomorrow. OUR SPONSOR Central Sikh Gurdwara Board would like to express their heartfelt thanks to our Patron, S. Naranjan Singh Brahmpura for sponsoring the cost of publishing this book. Naranjan Singh Brahmpura Patron Central Sikh Gurdwara Board Singapore Khalsa Association Trustee Singapore Sikh Education Foundation Sikh Welfare Council Past President Central Sikh Gurdwara Board Sri Guru Singh Sabha CONTENTS Foreword 6 Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Fast forward 9 1 Introduction 11 2 Singapore’s first Sikh 15 3 Sikh migration to Singapore: Phases and patterns 21 4 Early Sikh settlers in Singapore 31 5 Sikhs in the British Naval Base 39 6 Establishment of Gurdwaras, Sikh Advisory Board and other Sikh institutions 43 7 Sikh soldiers involvement in the defense of Singapore in World War II and civilian life during the Japanese Occupation 97 8 Early Sikh pioneers and their contributions to nation building 109 9 Colonial Singapore’s first Sikh politician 155 10.