Feeding Ecology of the Planehead Filefish Stephanolepis Hispidus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dedication Donald Perrin De Sylva

Dedication The Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Mangroves as Fish Habitat are dedicated to the memory of University of Miami Professors Samuel C. Snedaker and Donald Perrin de Sylva. Samuel C. Snedaker Donald Perrin de Sylva (1938–2005) (1929–2004) Professor Samuel Curry Snedaker Our longtime collaborator and dear passed away on March 21, 2005 in friend, University of Miami Professor Yakima, Washington, after an eminent Donald P. de Sylva, passed away in career on the faculty of the University Brooksville, Florida on January 28, of Florida and the University of Miami. 2004. Over the course of his diverse A world authority on mangrove eco- and productive career, he worked systems, he authored numerous books closely with mangrove expert and and publications on topics as diverse colleague Professor Samuel Snedaker as tropical ecology, global climate on relationships between mangrove change, and wetlands and fish communities. Don pollutants made major scientific contributions in marine to this area of research close to home organisms in south and sedi- Florida ments. One and as far of his most afield as enduring Southeast contributions Asia. He to marine sci- was the ences was the world’s publication leading authority on one of the most in 1974 of ecologically important inhabitants of “The ecology coastal mangrove habitats—the great of mangroves” (coauthored with Ariel barracuda. His 1963 book Systematics Lugo), a paper that set the high stan- and Life History of the Great Barracuda dard by which contemporary mangrove continues to be an essential reference ecology continues to be measured. for those interested in the taxonomy, Sam’s studies laid the scientific bases biology, and ecology of this species. -

A Survey of the Order Tetraodontiformes on Coral Reef Habitats in Southeast Florida

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks HCNSO Student Capstones HCNSO Student Work 4-28-2020 A Survey of the Order Tetraodontiformes on Coral Reef Habitats in Southeast Florida Anne C. Sevon Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University . For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU , please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cnso_stucap Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Anne C. Sevon. 2020. A Survey of the Order Tetraodontiformes on Coral Reef Habitats in Southeast Florida. Capstone. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, . (350) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cnso_stucap/350. This Capstone is brought to you by the HCNSO Student Work at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCNSO Student Capstones by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Capstone of Anne C. Sevon Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science M.S. Marine Environmental Sciences M.S. Coastal Zone Management Nova Southeastern University Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography April 2020 Approved: Capstone Committee Major Professor: Dr. Kirk Kilfoyle Committee Member: Dr. Bernhard Riegl This capstone is available at NSUWorks: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cnso_stucap/350 HALMOS -

Sharkcam Fishes

SharkCam Fishes A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower By Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie 1 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index Trevor Mendelow, designer of SharkCam, on August 31, 2014, the day of the original SharkCam installation. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition by Erin J. Burge, Christopher E. O’Brien, and jon-newbie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. For questions related to this guide or its usage contact Erin Burge. The suggested citation for this guide is: Burge EJ, CE O’Brien and jon-newbie. 2020. SharkCam Fishes. A Guide to Nekton at Frying Pan Tower. 5th edition. Los Angeles: Explore.org Ocean Frontiers. 201 pp. Available online http://explore.org/live-cams/player/shark-cam. Guide version 5.0. 24 February 2020. 2 Table of Contents Identification Images Species Profiles Additional Info Index TABLE OF CONTENTS SILVERY FISHES (23) ........................... 47 African Pompano ......................................... 48 FOREWORD AND INTRODUCTION .............. 6 Crevalle Jack ................................................. 49 IDENTIFICATION IMAGES ...................... 10 Permit .......................................................... 50 Sharks and Rays ........................................ 10 Almaco Jack ................................................. 51 Illustrations of SharkCam -

Marine Reconnaissance Survey of Proposed Sites for a Small Boat Harbor in Agat Bay, Guam

Ii MARINE RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY OF PROPOSED SITES FOR A SMALL BOAT HARBOR IN AGAT BAY, GUAM Mitchell 1. Chernin, Dennis R. Lassuy, Richard "E" Dickinson, and John W. Shepard II Submitted to !i U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Contract No. DACWB4-77-C-0061 I! I ~ Technical Report No. 39 University of Guam Marine Laboratory September 1977 , ,; , TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 METHODS 3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 5 Description of Study Sites 5 Macro-invertebrates 7 Marine Plants 13 Corals 22 Fishes 29 Currents 38 Water Quality 40 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 47 LITERATURE CITED 49 APPENDIX 50 LIST OF FIGURES 1. General location map for the Agat Bay study areas. 2. Map indicating general topographical features at the Nimitz and Ta1eyfac study sites. 6 3. Map indicating general topographical features at the Bangi site. 17 4. Current movement along three transects at the Bangi site at low tide. 41 5. Current movement along two transects at the Bangi site at high tide. 42 6. Current movement on the Northern (Tr.IV) and Center (Tr.V) reef flats and Nimitz Channel during high tide. 43 7. Current movement on the Northern and Center reef flats and Nimitz Channel during a falling tide. 44 8. Current movement on the Taleyfac reef flat and Ta1eyfac Bay during a falling tide. 45 9. Current movement on the Ta1eyfac reef flat (Tr.VI) and Taleyfac Bay during a rising tide. 46 A-1. Location of two fish transects at the Gaan site 51 A-2. Density of fishes in each 2D-meter transect interval of Transect A (Fig. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

The Teeth and Dentition of the Filefish (Stephanolepis Cirrhifer) Revisited Tomographically

1 J-STAGE Advance Publication: August 12, 2020 Journal of Oral Science Original article The teeth and dentition of the filefish (Stephanolepis cirrhifer) revisited tomographically Hirofumi Kanazawa1,2), Maki Yuguchi1,2,3), Yosuke Yamazaki1,2,3), and Keitaro Isokawa1,2,3) 1) Division of Oral Structural and Functional Biology, Nihon University Graduate School of Dentistry, Tokyo, Japan 2) Department of Anatomy, Nihon University School of Dentistry, Tokyo, Japan 3) Division of Functional Morphology, Dental Research Center, Nihon University School of Dentistry, Tokyo, Japan (Received October 31, 2019; Accepted November 26, 2019) Abstract: The upper and lower tooth-bearing jaws of the filefish (Stepha- Teeth of Non-Mammalian Vertebrates, Elsevier, 2017). nolepis cirrhifer) were scanned using a micro-CT system in order to With regard to filefish dentition in Japan, an early morphologic and address the existing gaps between the traditional pictures of the morphol- histologic study of Monocanthus cirrhifer and Cantherines modestus ogy and histology. 2D tomograms, reconstructed 3D models and virtual (synonyms Stephanolepis cirrhifer and Thamnaconus modestus, respec- dissection were employed to examine and evaluate the in situ geometry of tively) was carried out by Sohiti Isokawa (Isokawa, Zool Mag 64, 194-197, tooth implantation and the mode of tooth attachment both separately and 1955). Phylogenetic interrelationships in the balistoids were examined collectively. No distinct sockets comparable to those in mammals were extensively by Matsuura [4], based on many anatomical characteristics evident, but shallow depressions were observed in the premaxillary and including the tooth-bearing jaws, which were the premaxillary and the the dentary. The opening of the tooth pulp cavity was not simply oriented dentary. -

Large-Scale Spatial and Temporal Variability of Larval Fish Assemblages in the Tropical Atlantic Ocean

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2019) 91(1): e20170567 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201820170567 www.scielo.br/aabc | www.fb.com/aabcjournal Large-Scale Spatial and Temporal Variability of Larval Fish Assemblages in the Tropical Atlantic Ocean CHRISTIANE S. DE SOUZA and PAULO O. MAFALDA JUNIOR Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto de Biologia, Laboratório de Plâncton, Rua Ademar de Barros, s/n, Ondina, 40210-020 Salvador, BA, Brazil Manuscript received on July 28, 2017; accepted for publication on April 30, 2018 How to cite: SOUZA CS AND JUNIOR POM. 2019. Large-Scale Spatial and Temporal Variability of Larval Fish Assemblages in the Tropical Atlantic Ocean. An Acad Bras Cienc 91: e20170567. DOI 10.1590/0001- 3765201820170567. Abstract: This study investigated the large-scale spatial and temporal variability of larval fish assemblages in the west tropical Atlantic Ocean. The sampling was performed during four expeditions. Identification resulted in 100 taxa (64 families, 19 orders and 17 suborders). During the four periods, 80% of the total larvae taken represented eight characteristics families (Scombridae, Carangidae, Paralepididae, Bothidae, Gonostomatidae, Scaridae, Gobiidae and Myctophidae). Fish larvae showed a rather heterogeneous distribution with density at each station ranging from 0.5 to 2000 larvae per 100m3. A general trend was observed, lower densities at oceanic area and higher densities in the seamounts and islands. A gradient in temperature, salinity, phytoplankton biomass, zooplankton biomass and station depth was strongly correlated with changes in ichthyoplankton structure. Myctophidae, and Paralepididae presented increased abundance at high salinities and temperatures. -

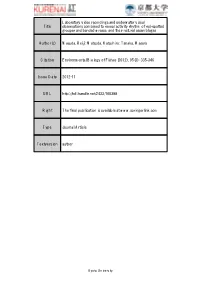

Title Laboratory Video Recordings and Underwater Visual Observations

Laboratory video recordings and underwater visual Title observations combined to reveal activity rhythm of red-spotted grouper and banded wrasse, and their natural assemblages Author(s) Masuda, Reiji; Matsuda, Katsuhiro; Tanaka, Masaru Citation Environmental Biology of Fishes (2012), 95(3): 335-346 Issue Date 2012-11 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/160388 Right The final publication is available at www.springerlink.com Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University 1 Laboratory video recordings and underwater visual observations combined to reveal activity rhythm of 2 red-spotted grouper and banded wrasse, and their natural assemblages 3 4 Reiji Masuda, Katsuhiro Matsuda, Masaru Tanaka 5 6 7 8 R. Masuda 9 Maizuru Fisheries Research Station, Kyoto University, Nagahama, Maizuru, Kyoto 6250086, Japan 10 e-mail: [email protected] 11 Telephone: +81-773-62-9063, Fax: +81-773-62-5513 12 13 K. Matsuda 14 Kyushu Branch, Ajinomoto Co., Inc., 3-3-31 Ekiminami, Hakata, Fukuoka 8128683, Japan 15 16 M. Tanaka 17 International Institute for Advanced Studies, 9-3 Kizugawadai, Kizugawa-shi, Kyoto 6190225, Japan 1 18 Abstract The diel activity rhythm of red-spotted grouper Epinephelus akaara was studied both in 19 captivity and in the wild. Behavior of solitary grouper (58 to 397 mm in total length) in a tank was video 20 recorded using infrared illuminators under 11L/10D and two 1.5-h twilight transition periods, and was 21 compared to that of banded wrasse Halichoeres poecilopterus, a typical diurnal fish. Underwater 22 observations using SCUBA were also conducted in their natural habitat to reveal the behavioral activity 23 together with a visual census of adjacent fish and crustacean assemblages. -

Vertical Distribution and Feeding Ecology of the Black Scraper, Thamnaconus Modestus, in the Southern Sea of Korea

www.trjfas.org ISSN 1303-2712 Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 13: 249-259 (2013) DOI: 10.4194/1303-2712-v13_2_07 Vertical Distribution and Feeding Ecology of the Black Scraper, Thamnaconus modestus, in the Southern Sea of Korea Hye Rim Kim1, Jung Hwa Choi1,*, Won Gyu Park2 1 National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Busan 619-705, Korea. 2 Pukyong National University, Department of Marine Biology, , Busan 608-737, Korea. * Corresponding Author: Tel.: 82-51-270-2291; Fax: 82-51-270-2291; Received 02 October 2012 E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 01 April 2013 Abstract We investigated the vertical distribution and feeding ecology of the black scraper, Tamnaconus modestus, in the southern sea of Korea in the spring of 2009, 2010 and 2011 using otter trawl for 60 min per site. Fish abundance was significantly related to the basis of depth and temperature. Thamnaconus modestus occurred at depths ranging from 80 to 120 meter waters having temperature higher than 12°C. We found that 87% of the total catch were obtained at the depths between 80 and 120 meters (58% and 29% from 80–100 and 100–120 meters respectively). The total length of captured individuals ranged from 10.6 to 38.7 cm. Individuals captured at deeper were significantly larger than those from shallower sites. Diverse prey organisms, including algae, amphipods, gastropods, ophiuroids, and cephalopods, were found in T. modestus stomach. The main prey items in IRI value belonged to four groups: hyperiid amphipods, gastropods, ophiuroids, and algae. The fish showed ontogenetic diet shifts. In general, individuals in smaller size (< 20 cm) shifted their diets from vegetative food sources to animal ones when they reach the size bigger than 20 cm. -

Parasitic Copepods of Marine Fish Cultured in Japan: a Review Kazuya Nagasawa*

Journal of Natural History, 2015 Vol. 49, Nos. 45–48, 2891–2903, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2015.1022615 Parasitic copepods of marine fish cultured in Japan: a review Kazuya Nagasawa* Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan (Received 22 September 2014; accepted 4 February 2015; first published online 29 June 2015) This paper reviews aspects of the biology of copepods infecting marine fish commer- cially cultured at fish farms or held as broodstock at governmental hatcheries in Japan. In total, 20 species of parasitic copepods have been reported from these fish: they are mostly caligids (12 spp.), followed by lernaeopodids (4 spp.), pennellid (1 sp.), chondracanthid (1 sp.), taeniacanthid (1 sp.), and unidentified species (1 sp.). The identified copepods are: Caligus fugu, C. lagocephalus, C. lalandei, C. latigenitalis, C. longipedis, C. macarovi, C. orientalis, C. sclerotinosus, C. spinosus, Lepeophtheirus longiventralis, L. paralichthydis, L. salmonis (Caligidae); Alella macrotrachelus, Clavella parva, Parabrachiella hugu, P. seriolae (Lernaeopodidae); Peniculus minuti- caudae (Pennellidae); Acanthochondria priacanthi (Chondracanthidae); and Biacanthus pleuronichthydis (Taeniacanthidae). The fish recorded as hosts include carangids (4 spp.), sparids (2 spp.), monacanthids (2 spp.), salmonids (2 spp.), scom- brid (1 sp.), tetraodontid (1 sp.), pleuronectid (1 sp.), paralichthyid (1 sp.), and trichodontid (1 sp.). Only five species (C. orientalis, L. longiventralis, L. salmonis, C. parva and A. priacanthi) parasitize farmed fish in subarctic waters, while all other species (15 spp.) infect farmed fish in temperate waters. No information is yet avail- able on copepods from fish farmed in subtropical waters. Three species of Caligus (C. fugu, C. sclerotinosus and C. -

Marine Fishes of the Azores: an Annotated Checklist and Bibliography

MARINE FISHES OF THE AZORES: AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. RICARDO SERRÃO SANTOS, FILIPE MORA PORTEIRO & JOÃO PEDRO BARREIROS SANTOS, RICARDO SERRÃO, FILIPE MORA PORTEIRO & JOÃO PEDRO BARREIROS 1997. Marine fishes of the Azores: An annotated checklist and bibliography. Arquipélago. Life and Marine Sciences Supplement 1: xxiii + 242pp. Ponta Delgada. ISSN 0873-4704. ISBN 972-9340-92-7. A list of the marine fishes of the Azores is presented. The list is based on a review of the literature combined with an examination of selected specimens available from collections of Azorean fishes deposited in museums, including the collection of fish at the Department of Oceanography and Fisheries of the University of the Azores (Horta). Personal information collected over several years is also incorporated. The geographic area considered is the Economic Exclusive Zone of the Azores. The list is organised in Classes, Orders and Families according to Nelson (1994). The scientific names are, for the most part, those used in Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean (FNAM) (Whitehead et al. 1989), and they are organised in alphabetical order within the families. Clofnam numbers (see Hureau & Monod 1979) are included for reference. Information is given if the species is not cited for the Azores in FNAM. Whenever available, vernacular names are presented, both in Portuguese (Azorean names) and in English. Synonyms, misspellings and misidentifications found in the literature in reference to the occurrence of species in the Azores are also quoted. The 460 species listed, belong to 142 families; 12 species are cited for the first time for the Azores.