HOW WEEVILS GET INTO BEANS. the New England Farmer Strouing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Genetic Dissection of Azuki Bean Weevil (Callosobruchus Chinensis L.) Resistance in Moth Bean (Vigna Aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9543/genetic-dissection-of-azuki-bean-weevil-callosobruchus-chinensis-l-resistance-in-moth-bean-vigna-aconitifolia-jaqc-mar%C3%A9chal-59543.webp)

Genetic Dissection of Azuki Bean Weevil (Callosobruchus Chinensis L.) Resistance in Moth Bean (Vigna Aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal)

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Genetic Dissection of Azuki Bean Weevil (Callosobruchus chinensis L.) Resistance in Moth Bean (Vigna aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal) Prakit Somta 1,2,3,* , Achara Jomsangawong 4, Chutintorn Yundaeng 1, Xingxing Yuan 1, Jingbin Chen 1 , Norihiko Tomooka 5 and Xin Chen 1,* 1 Institute of Industrial Crops, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 50 Zhongling Street, Nanjing 210014, China; [email protected] (C.Y.); [email protected] (X.Y.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand 3 Center for Agricultural Biotechnology (AG-BIO/PEDRO-CHE), Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand 4 Program in Plant Breeding, Faculty of Agriculture at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73140, Thailand; [email protected] 5 Genetic Resources Center, Gene Bank, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, 2-1-2 Kannondai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8602, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (X.C.) Received: 3 September 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018; Published: 15 November 2018 Abstract: The azuki bean weevil (Callosobruchus chinensis L.) is an insect pest responsible for serious postharvest seed loss in leguminous crops. In this study, we performed quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping of seed resistance to C. chinensis in moth bean (Vigna aconitifolia [Jaqc.] Maréchal). An F2 population of 188 plants developed by crossing resistant accession ‘TN67’ (wild type from India; male parent) and susceptible accession ‘IPCMO056’ (cultivated type from India; female parent) was used for mapping. -

Nghiên Cứu Thành Phần Mọt Hại Ngô Sau

VIỆN HÀN LÂM KHOA HỌC BỘ GIÁO DỤC VÀ ĐÀO TẠO VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ VIỆT NAM HỌC VIỆN KHOA HỌC VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ ----------------------------- NGUYỄN VĂN DƯƠNG NGHIÊN CỨU THÀNH PHẦN MỌT HẠI NGÔ SAU THU HOẠCH VÀ ẢNH HƯỞNG CỦA MỘT SỐ YẾU TỐ SINH THÁI ĐẾN SỰ PHÁT TRIỂN CỦA LOÀI MỌT Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky TRONG KHO BẢO QUẢN Ở SƠN LA LUẬN ÁN TIẾN SĨ SINH HỌC Hà Nội – 2021 VIỆN HÀN LÂM KHOA HỌC BỘ GIÁO DỤC VÀ ĐÀO TẠO VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ VIỆT NAM HỌC VIỆN KHOA HỌC VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ ----------------------------- NGUYỄN VĂN DƯƠNG NGHIÊN CỨU THÀNH PHẦN MỌT HẠI NGÔ SAU THU HOẠCH VÀ ẢNH HƯỞNG CỦA MỘT SỐ YẾU TỐ SINH THÁI ĐẾN SỰ PHÁT TRIỂN CỦA LOÀI MỌT Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky TRONG KHO BẢO QUẢN Ở SƠN LA Chuyên ngành: Sinh thái học Mã số: 9 42 01 20 Người hướng dẫn khoa học: 1. PGS.TS. Khuất Đăng Long 2. PGS.TS. Lê Xuân Quế Hà Nội – 2021 LỜI CAM ĐOAN Để đảm bảo tính trung thực của luận án, tôi xin cam đoan: Luận án “Nghiên cứu thành phần mọt hại ngô sau thu hoạch và ảnh hưởng của một số yếu tố sinh thái đến sự phát triển loài mọt Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky trong kho bảo quản ở Sơn La”. Là công trình nghiên cứu của cá nhân tôi, dưới sự hướng dẫn khoa học của PGS.TS. Khuất Đăng Long và PGS.TS. Lê Xuân Quế, các tài liệu tham khảo đều được trích nguồn. Các kết quả trình bày trong luận án là trung thực và chưa từng được công bố ở bất kì công trình nào trước đây./. -

Callosobruchus Spp.) in Vigna Crops: a Review

NU Science Journal 2007; 4(1): 01 - 17 Genetics and Breeding of Resistance to Bruchids (Callosobruchus spp.) in Vigna Crops: A Review Peerasak Srinives1*, Prakit Somta1 and Chanida Somta2 1Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agriculture at Kamphaeng Saen, Kasetsart University, Nakhon Parham, 73140 Thailand 2Asian Regional Center, AVRDC-The World Vegetable Center, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom, 73140 Thailand *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Vigna crops include mungbean (V. radiata), blackgram (V. mungo), azuki bean (V. angularis) and cowpea (V. unguiculata) are agriculturally and economically important crops in tropical and subtropical Asia and/or Africa. Bruchid beetles, Callosobruchus chinensis (L.) and C. maculatus (F.) are the most serious insect pests of Vigna crops during storage. Use of resistant cultivars is the best way to manage the bruchids. Bruchid resistant cowpea and mungbean have been developed and comercially used, each with single resistance source. However, considering that enough time and evolutionary pressure may lead bruchids to overcome the resistance, new resistance sources are neccessary. Genetics and mechanism of the resistance should be clarified and understood to develop multiple resistance cultivars. Gene technology may be a choice to develop bruchid resistance in Vigna. In this paper we review sources, mechanism, genetics and breeding of resistance to C. chinensis and C. maculatus in Vigna crops with the emphasis on mungbean, blackgram, azuki bean and cowpea. Keywords: Bruchid resistance, Callosobruchus spp., Legumes, Vigna spp. INTRODUCTION The genus Vigna falls within the tribe Phaseoleae and family Fabaceae. Species in this taxon mainly distribute in pan-tropical Asia and Africa. Seven Vigna species are widely cultivated and known as food legume crops. -

The Development and Use of Varieties of Beans Resistant to Certain Insect Pests of Legumes

THE DEVELOPMENT AND USE OF VARIETIES OF BEANS RESISTANT TO CERTAIN INSECT PESTS OF LEGUMES, DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By JOSE CALDERON GUEVARA, Ing. Agr., M. Sc. The Ohio State University. 1957 Approved by: CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ...................... 1 REVIEW OE LITERATURE ............................. 4 Insect Outbreaks .................... 4 Food Plant Selection by Insects ................ 11 The Mechanisms of Resistance .................. 14 Cause of Resistance ........................... 18 Factors that Affect the Expression or the Permanence of Resistance .................. 22 SYNOPSIS OF THE BIOLOGY OF THE APION POD WEEVIL .... 29 SELECTION OF VARIETIES RESISTANT TO THE APION POD WEEVIL, APION GODMANI WAG................... 30 Seasonal infestation of A. godmani Wagner in Susceptible Varieties .............. 31 Investigation of the Cause of Resistance on beans to Apion godmani Wagner ........... 37 Crossing Program for A. godmani Resistance ....... 42 Classification of Bean Varieties and Lines ac cording to Resistance to the ApionPod Weevil .. 49 NOTES ON THE BIOLOGY OF THE SEED CORN MAGGOT IN MEXICO .... 52 Experiments on Seed Color Preference of Hylemya cilicrura .................................. 59 Preliminary Selection of Resistant Varieties to the Seed Corn Maggot ........... 61, ii PRELIMINARY EXPERIMENTS ON THE SELECTION. OF BEAN VARIETIES RESISTANT TO THE POTATO LEAFHOPPER .... 64 Experiments at the University Farm, Columbus,Ohio. 67 Experimental Designs ........................... 67 Relationship Between the Potato Leafhopper and Bean Plants ................................. 68 Leafhopper Damage .................... ......... 69 Recuperation of the Bean Plant from Insect Attack and Seasonal Differences .............. 72 Effect of Weather on the Potato Leafhopper and the Bean Plant .............................. 76 Tolerance of Different Bean Varieties to the Potato Leafhopper ..... -

General-Poster

XXIV International Congress of Entomology General-Poster > 157 Section 1 Taxonomy August 20-22 (Mon-Wed) Presentation Title Code No. Authors_Presenting author PS1M001 Madagascar’s millipede assassin bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Ectrichodiinae): Taxonomy, phylogenetics and sexual dimorphism Michael Forthman, Christiane Weirauch PS1M002 Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Papilio memnon complex suggests multiple origins of mimetic colour pattern and sexual dimorphism Chia-Hsuan Wei, Matheiu Joron, Shen-HornYen PS1M003 The evolution of host utilization and shelter building behavior in the genus Parapoynx (Lepidoptera: Crambidae: Acentropinae) Ling-Ying Tsai, Chia-Hsuan Wei, Shen-Horn Yen PS1M004 Phylogenetic analysis of the spider mite family Tetranychidae Tomoko Matsuda, Norihide Hinomoto, Maiko Morishita, Yasuki Kitashima, Tetsuo Gotoh PS1M005 A pteromalid (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) parasitizing larvae of Aphidoletes aphidimyza (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) and the fi rst fi nding of the facial pit in Chalcidoidea Kazunori Matsuo, Junichiro Abe, Kanako Atomura, Junichi Yukawa PS1M006 Population genetics of common Palearctic solitary bee Anthophora plumipes (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae) in whole species areal and result of its recent introduction in the USA Katerina Cerna, Pavel Munclinger, Jakub Straka PS1M007 Multiple nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analyses support a cryptic species complex of the global invasive pest, - Poster General Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Chia-Hung Hsieh, Hurng-Yi Wang, Cheng-Han Chung, -

An Annotated Bibliography of Archaeoentomology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects Entomology, Department of 4-2020 An Annotated Bibliography of Archaeoentomology Diana Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entodistmasters Part of the Entomology Commons This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Distance Master of Science in Entomology Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Diana Gallagher Master’s Project for the M.S. in Entomology An Annotated Bibliography of Archaeoentomology April 2020 Introduction For my Master’s Degree Project, I have undertaken to compile an annotated bibliography of a selection of the current literature on archaeoentomology. While not exhaustive by any means, it is designed to cover the main topics of interest to entomologists and archaeologists working in this odd, dark corner at the intersection of these two disciplines. I have found many obscure works but some publications are not available without a trip to the Royal Society’s library in London or the expenditure of far more funds than I can justify. Still, the goal is to provide in one place, a list, as comprehensive as possible, of the scholarly literature available to a researcher in this area. The main categories are broad but cover the most important subareas of the discipline. Full books are far out-numbered by book chapters and journal articles, although Harry Kenward, well represented here, will be publishing a book in June of 2020 on archaeoentomology. -

Biology and Biointensive Management of Acanthoscelides Obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) – a Pest of Kidney Beans Wordwide

11th International Working Conference on Stored Product Protection Biology and biointensive management of Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) – a pest of kidney beans wordwide Thakur, D.R.*#, Renuka Department of Biosciences, Himachal Pradesh University, Summerhill, Shimla 171005, India *Corresponding author, Email: [email protected], [email protected] #Presenting author, Email: [email protected] [email protected] DOI: 10.14455/DOA.res.2014.24 Abstract Insects in the family Bruchidae are commonly called “pulse weevils” and are cosmopolitan in distribution. These beetles cause serious economic loss of legume commodities both in fields and every year. Pulses constitute the main source of protein for developing countries like India where per capita consumption of animal protein is very low. Due to their high protein quantity and quality, legumes are considered as “poor man‟s meat”. A large number of non-native pulse beetles have crossed geographical boundaries and becoming cosmopolitan in distribution, thus posing major pest problem worldwide. A kidney bean pest, Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) native to Central and Southern America has recently infested stored kidney beans in the Indian subcontinent. The present investigations determined life cycle, behaviour, facundity, pest status, host range and developmental compatibility on diffent legumes and different cultivars of kidney beans. Acetone and alcoholic extracts of some botanicals have been tested and proved effective to suppress facundity, egg hatch and adult longivity of the pest population under laboratory conditions. Keywords: Acanthoscelides obtectus, biology, resistance, developmental compatiblity, botanical management 1. Introduction Most pulses have 17-24% protein content which are 2.3 times higher than traditional cereals. Any stored materials of plant origin are vulnerable to attack by insect pests if the pulses are dried and stored improperly. -

Insects Injurious to Beans and Peas

INSECTS INJURIOUS TO BEANS AND PEAS. By F. H. CHITTENDEN, Assistant Entomologist, INTRODUCTION. Beans, peas, cowpeas, and other edible legumes are subject to injury by certain species of beetles, commonly known as weevils, which deposit their eggs upon or within the pods on the growing plants in the field or garden and develop Ivithin the seed. Four forms of these weevils, members of the genus Bruchus of the family Bru- chidae, which inhabit the United States, are very serious drawbacks to the culture of these crops in many portions of the country. The spe- cific enemy of the pea is the pea weevil, and of the bean, the common bean weevil, both of sufficiently wide distribution and abundance to hold the highest rank among injurious insects.- Cowpeas are attacked by two species of these beetles, known, respectively, as the four- spotted bean weevil and the cowpea weevil. These latter are of con- siderable importance economically in the Southern States and in tropical climates, as well as in northern localities in which cowpeas are grown or to which they are from time to time shipped in seed from the South and from abroad. As with the insects that live upon stored cereals, the inroads of the larvse of these weevils in leguminous seeds cause great waste, and particularly is this true of beans that are kept hi store for any considerable time. In former times popular opinion held that the germination of leguminous food seed was not impaired by the action of the larval beetle in eating out its interior, but this belief was erroneous, as will be shown in the discussion of the nature of the damage by the pea weevil. -

Micro-CT to Document the Coffee Bean Weevil, Araecerus Fasciculatus (Coleoptera: Anthribidae), Inside Field-Collected Coffee Berries (Coffea Canephora)

insects Communication Micro-CT to Document the Coffee Bean Weevil, Araecerus fasciculatus (Coleoptera: Anthribidae), Inside Field-Collected Coffee Berries (Coffea canephora) Ignacio Alba-Alejandre 1 ID , Javier Alba-Tercedor 1 ID and Fernando E. Vega 2,* ID 1 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Granada, Campus de Fuentenueva, 18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] (I.A.-A.); [email protected] (J.A.-T.) 2 Sustainable Perennial Crops Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-504-5101 Received: 22 June 2018; Accepted: 10 August 2018; Published: 14 August 2018 Abstract: The coffee bean weevil, Araecerus fasciculatus (De Geer) (Coleoptera: Anthribidae), is a cosmopolitan insect with >100 hosts, and has been reported as a pest of stored coffee. During a study involving the coffee berry borer, we observed coffee bean weevils emerging from field-collected coffee berries and used micro-computerized tomography (micro-CT) scans to observe the insect inside the berry. Two eggs had eclosed inside the berry, resulting in observations of a newly eclosed adult beetle and a 5th instar larva, each feeding on one of the two seeds. This is the first time since 1775, when the insect was first described, that the insect has been observed inside a coffee berry. Keywords: coffee quality; insect biology; losses; stored coffee; stored product pest 1. Introduction The genus Araecerus Schönherr comprises ca. 75 species [1], with the coffee bean weevil, Araecerus fasciculatus (De Geer) (Coleoptera: Anthribidae), being the most economically important. Chittenden [2,3] coined the name coffee bean weevil and Valentine [1] has published a succinct account on the controversy involving the many different scientific names used for the insect. -

| the Old Smuggler Whose Tiicuring Announced Their Majes Gnlldhall, Irtilch Coetalne Priceleea City Missioner in Somaliland and Commander Age with the Powder

Nesbitt Z Truscott Vapor Electric Co. Launches w foer eiBerr. ♦ IW* M. f. O. Box ist NESBirr ELECTRIC viotoeiA, b. o. ■ CO Afaotl, U Port Street VOL. SS. VICTORIA, B. C., SATURDAY. OCTOBSK 25, I90S. Ho. 150. - --ID- ' -i ' il than those directly toodting on the wet- ; by fraud and undue Influence. An Id- fare of the poored* chutes of this and 1 junction restraining tue defendant from In other gfeat cities. any way parting with, disposing of or deal ROMPROCE» ing with the property which be derived “I thank yon for your good wishes for THREE RIRES TO from tue estât* of Alex. Duusmulr 1» also HOD POWDER IH myself and my hoes^ Tt cordially share claimed, and the appointment of a re ycur aspiration thatv it may be granted ceiver Is asked. wearing roe by the same divide providence which There was no business In Chambers this HOOCH MR IEEÎET BOOTH morning. E POSSESSION preserved my life on* imminent} dan ger to reign -over m; flrtnly established SEVENTY SOLDIERS KILLED. CHAIN and peaceful and in the loyal HEARTY RECEPTION hearts y of my ooni and prosperous OUTCOME WILL BE Details of Engagement Between British Troops and Followers of the CLERGYMAN ARRESTED OF THEIR MAJESTIES The Interior of the great hall of the WATCHED WITH INTEREST Mad Mullah. IN LONDON TO-DAY b* Gold Ladies’Lon* Guildhall presented « brilliant scene. It was filled with members of the Royal (Associated Press.* Fllkd Ch* ins Gold Filled family and diplomat», officers and offi Aden, Arabia, Oct. 26.—Details of the Chains as The Beg’s Reply to an Address of cials, $11 In full uniform with their fighting in Somaliland on October 6th «* Uv 41 breast^ biasing wtfh orders. -

Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae

JapaneseJapaneseSociety Society of AppliedApplied Entomology and Zoology AppL Entomol. ZooL 42 (3): 337-346 (2007) http/]todokon.orgl Review Applied evolutionary ecology of insects of the subfamily Bruchinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Midori TuDA" Institute ofBiological Centrol, Faculty of Agriculturc, Kyushu Univcrsity; Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan (Reccis,ed 17 October 2006; Accepted 19 January 2007) Abstract Bean beetles ofthe subfamily Bruchinae (formerly, the family Bruchidae) include notorious pests of stored legumes, Callosobrttchus, CaEyedon, Aeanthoscetides and Zdbrotes that are able to feed and reproduce on dricd bcans and peas. Here, I review recent findings on the ecology, phylogeny, invasion and evolution in the bean beetles, based on field in- vestigation of host plants and rnolecular studies. Possible future application ofthe new knowledge to weed and pest control is proposea such as potential utility of the seed predators for modest control of beneficial yet invasive (`con- flict') plants and new control methodology ofpcst bcan bcctlcs. Key words: Bruchidae; seed predators; stored product pests; biological weed control; molecular phylogeny stored-bean Strictly speaking, however, the INTRODUCTION pests. genus Bruchus is different from other stored-bean Beetles ofthe subfamily Bruchinae (Coleoptera:pests in that it does not reproduce on dried hard- Chrysomelidae) are specialized internal feeders of ened beanslpeas and thus cannot cause further bean family seeds (Fabaceae). They are fi:equently damage in storage. `weevils' and erroneously referred to as the bean in spite of their aMnity to the leaf beetles PHYLOGENY (Chrysomelidae), Here, I use the common name, `beetle' `beetle') the bean (or the seed to avoid tax- Recent molecular studies support that the onomic confusion, I also fo11ow the recent taxo- Bruchinae are closely related to the fi;og-legged nomic consideration that the bean beetle is not beetle subfamily, Sagrinae, within the family unique enough as a family but as a subfamily of Chrysomelidae (Farre}1 and Sequeira, 2004). -

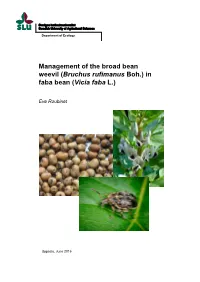

Management of the Broad Bean Weevil (Bruchus Rufimanus Boh.) in Faba Bean (Vicia Faba L.)

Department of Ecology Management of the broad bean weevil (Bruchus rufimanus Boh.) in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) Eve Roubinet Uppsala, June 2016 Management of the broad bean weevil (Bruchus rufimanus Boh.) in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) Eve Roubinet [email protected] Reviewer of language: Riccardo Bommarco Place of publication: Uppsala, Sweden Year of publication: 2016 Cover pictures: M. Massie (B. rufimanus adult) B. Luka, INRA (Infested faba beans) Australian Department of Food and Agriculture (V. faba in bloom) Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Department of Ecology Contents Summary .............................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 7 Faba bean production in Sweden ..................................................................... 7 Pest pressure in Sweden and Northern Europe ................................................ 7 Biology of the broad bean weevil ........................................................................ 8 Life cycle ......................................................................................................... 9 Overwintering .............................................................................................. 9 Field colonization, mobility and sexual maturity ...................................... 10 Mating and oviposition .............................................................................